V-2 rocket facts for kids

Quick facts for kids V2 |

|

|---|---|

Peenemünde Museum replica of V2

|

|

| Type | Single-stage ballistic missile |

| Place of origin | Nazi Germany |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1944–1952 |

| Used by | |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Peenemünde Army Research Center |

| Manufacturer | Mittelwerk GmbH |

| Unit cost |

|

| Produced |

|

| No. built | Over 3,000 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 12,500 kg (27,600 lb) |

| Length | 14 m (45 ft 11 in) |

| Diameter | 1.65 m (5 ft 5 in) |

| Warhead | 1,000 kg (2,200 lb); Amatol (explosive weight: 910 kg) |

|

Detonation

mechanism |

Impact |

|

|

|

| Wingspan | 3.56 m (11 ft 8 in) |

| Propellant |

|

|

Operational

range |

320 km (200 mi) |

| Flight altitude |

|

| Maximum speed |

|

|

Guidance

system |

|

|

Launch

platform |

Mobile (Meillerwagen) |

The V2 (which means "Vengeance Weapon 2" in German) was the world's first long-range guided missile. It was a type of ballistic missile powered by a special liquid fuel engine. This rocket was created in Nazi Germany during Second World War. It was meant to be a "vengeance weapon" to attack cities of the Allied countries. This was in response to the Allied bombings of German cities.

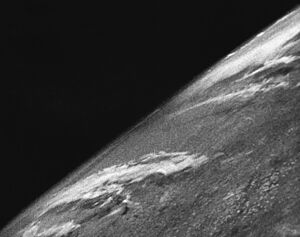

The V2 rocket also made history by becoming the first object made by humans to travel into space. It crossed the Kármán line, which is considered the edge of space. This happened on June 20, 1944, with a rocket called MW 18014.

Work on military rockets began when the German Army noticed the studies of a scientist named Wernher von Braun. Many test rockets were built, leading to the V2. Starting in September 1944, the German army launched over 3,000 V2s. They targeted cities like London, Antwerp, and Liège. These attacks caused the deaths of about 9,000 civilians and soldiers. Also, around 12,000 forced laborers died while making these weapons.

The rockets flew extremely fast, faster than the speed of sound. They hit their targets without any warning sound and could not be stopped. There was no defense against them. After the war, teams from the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and the Soviet Union rushed to get German rocket factories and technology. Wernher von Braun and over 100 V2 scientists surrendered to the Americans. Many of them moved to the United States to continue their work. The Soviets took over the V2 factories and started making the rockets in the Soviet Union.

Contents

How the V2 Rocket Was Developed

Early Rocket Ideas and Tests

In the late 1920s, a young Wernher von Braun read a book about space travel. At that time, there was a lot of excitement about rockets. People like Fritz von Opel and Max Valier were doing public shows with rocket-powered cars and planes. Von Braun was very excited by this. He even built his own toy rocket car and launched it, which got him into a bit of trouble with the police!

In 1930, von Braun started studying at a technical university in Berlin. There, he helped with tests on rockets that used liquid fuel. When the Nazi Party came to power, an army captain named Walter Dornberger helped von Braun get a research grant. Von Braun then worked on rockets next to Dornberger's test site. By the end of 1934, his team had successfully launched two rockets that flew several kilometers high.

German engineers were also interested in the work of American physicist Robert H. Goddard. Before 1939, German scientists sometimes contacted Goddard for technical advice. Von Braun used Goddard's ideas to help build the "Aggregate" (A) series of rockets.

After some successful small rockets, von Braun and Walter Riedel started thinking about a much bigger rocket in 1936. The army wanted a rocket that could carry a 1-ton payload, fly 172 miles, and be moved easily by road.

Designing the A-4 Rocket

The A-4 project, which became the V2, faced some challenges early on. But after many tests with a smaller model called the A-5, the design for the A-4 was approved around 1938–39. By late 1941, the Peenemünde Army Research Center had all the necessary technology for the A-4. This included powerful liquid-fuel engines, ways to make the rocket fly well at very high speeds, and systems to guide it.

At first, Adolf Hitler was not very impressed with the V2. He thought it was just an expensive artillery shell with a longer range. However, the rocket's developers were very enthusiastic. Hitler eventually saw it as a "wonder weapon" that could boost German morale. So, he allowed it to be built in large numbers.

The V2 rockets were built at a place called Mittelwerk. Prisoners from the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp were forced to work there. Around 20,000 prisoners died during this work.

In 1943, an Austrian resistance group managed to send detailed drawings of the V2 rocket to the American intelligence agency. They also sent maps of the V-rocket factories, like the one in Peenemünde. This information helped Allied bombers plan airstrikes. These attacks were important for missions like Operation Crossbow and Operation Hydra. Sadly, many members of the resistance group were caught and executed.

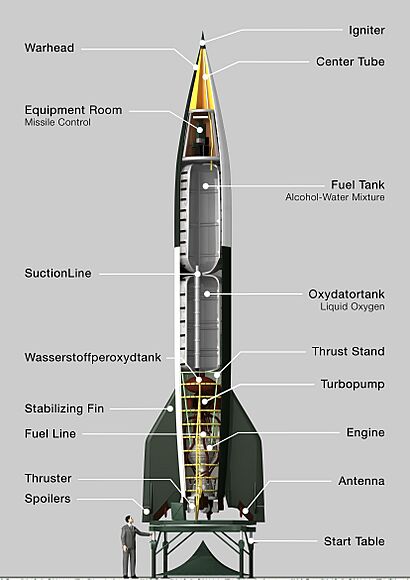

How the V2 Rocket Worked

The V2 rocket used a mix of 75% ethanol (alcohol) and 25% water as fuel. It also used liquid oxygen as an oxidizer, which helps the fuel burn. The water in the fuel helped cool the engine and made the burning smoother.

Scientists used a special wind tunnel to test how the A4 would fly at very high speeds. They used a model of the rocket to measure its flight characteristics.

When launched, the A4 rocket powered itself for about 65 seconds. A special motor kept it at the correct angle. After the engine shut down, the rocket continued flying in a free-fall path. It could reach a height of 80 kilometers (about 50 miles) after its engine stopped.

The fuel and oxygen were pumped into the engine by a steam turbine. This steam was made by mixing concentrated hydrogen peroxide with a special chemical called sodium permanganate. Both the alcohol and oxygen tanks were made from a light metal alloy.

The pumps spun very fast, pushing the fuel and oxygen into the engine's combustion chamber. There, they were ignited by an electric spark. The rocket weighed 13.5 tons, and its engine produced a huge amount of thrust to lift it off the ground. Hot gases shot out of the engine at a speed of 2,000 meters (about 6,500 feet) per second.

Warhead and Guidance System

The V2's warhead was another important part. It contained a powerful explosive called amatol. This explosive was very stable and was protected by a thick layer of glass wool. Even so, the warhead could sometimes explode when re-entering the atmosphere. The warhead weighed 975 kg (about 2,150 pounds) and contained 910 kg (about 2,000 pounds) of explosive. This meant a very high percentage of the warhead's weight was explosive.

The glass wool also helped keep the fuel tanks from freezing. This was a problem for other early rockets. The tanks held about 4,173 kg (9,200 pounds) of alcohol and 5,553 kg (12,240 pounds) of oxygen.

The V2 was guided by four rudders on its tail fins and four special graphite vanes inside the engine's exhaust stream. These eight control surfaces were moved by an analog computer based on signals from gyroscopes. The guidance system helped keep the rocket stable and on course.

Some later V2s used "guide beams" – radio signals from the ground – to stay on track. But the first models used a simpler computer. The rocket's flying distance was controlled by when its engine shut off. This was done either by a Doppler system or by special on-board accelerometers. This meant the rocket would fly further if its engine burned longer.

The V2 rockets were usually painted with a ragged pattern of different colors. But near the end of the war, some were plain olive green. During tests, the rockets were painted with a black-and-white chessboard pattern. This helped engineers see if the rocket was spinning during flight.

Testing the V2 Rocket

The first successful test flight of the V2 was on October 3, 1942. It reached an altitude of 84.5 kilometers (about 52.5 miles). On that day, Walter Dornberger announced that it was the start of a new era in space travel.

Two test rockets were found by the Allies. One landed in Sweden in June 1944. Another was found by the Polish resistance in May 1944 and sent to the UK. The highest altitude reached by a V2 during the war was 174.6 kilometers (about 108.5 miles) on June 20, 1944. Tests were done in Germany and Poland. After the war, tests continued in the UK, US, and USSR.

Solving Flight Problems

Engineers faced and solved several problems while developing the V2:

- They used fast pumps to increase fuel pressure and reduce tank weight.

- They designed a shorter, lighter engine combustion chamber to prevent it from burning through.

- Special film cooling was used to protect the nozzle from extreme heat.

- They made relay contacts stronger to handle vibrations and prevent early engine shutdown.

- Fuel pipes were designed with curves to prevent explosions during flight.

- The fins were shaped to avoid damage as the exhaust jet expanded at high altitudes.

- Heat-resistant graphite vanes were used in the exhaust to control the rocket's path at launch and supersonic speeds.

The Air Burst Problem

By early 1944, many V2 rockets were breaking apart in the air when they re-entered the atmosphere. This was a big problem. At first, German developers thought it was due to too much pressure in the alcohol tank. But they couldn't figure out the exact cause for months.

Finally, they tested rockets with a special "tin trousers" tube designed to strengthen the front part of the rocket's outer shell. These tests confirmed that the 'tin trousers' helped stop the rockets from breaking apart in the air.

Making the V2 Rockets

In March 1942, plans were made to produce the V2 and build launch sites. Factories were set up at Peenemünde and in Friedrichshafen. In 1943, another factory, Raxwerke, was added.

On December 22, 1942, Hitler ordered mass production of the V2. However, many problems still needed to be solved even by late 1943.

In May 1943, a commission met to review the V-1 and V2 weapons. They decided to recommend mass production of both to Hitler. They believed the two weapons would balance each other out.

| Period of production | Production |

|---|---|

| Up to 15 September 1944 | 1,900 |

| 15 September to 29 October 1944 | 900 |

| 29 October to 24 November 1944 | 600 |

| 24 November to 15 January 1945 | 1,100 |

| 15 January to 15 February 1945 | 700 |

| Total | 5200 |

In July 1943, Major General Dornberger and von Braun showed Hitler a movie of a successful V2 launch. Hitler was very impressed. He gave the Peenemünde project top priority. He said if they had these rockets in 1939, the war might not have happened.

A production line was almost ready at Peenemünde when the Allies attacked the site in Operation Hydra. The attack caused some damage, but work resumed after a few weeks. The Germans later moved V2 production underground to the Mittelwerk factory. There, 5,200 V2 rockets were built using forced labour.

Where V2 Rockets Were Launched

After Allied bombings, plans to launch V2s from huge underground bunkers were dropped. Instead, the Germans decided to use mobile launch platforms. This meant the missile could be launched almost anywhere, often from roads in forests. The system was so mobile that Allied planes rarely caught a launch in action.

It was thought that 350 V2s could be launched per week, or even 100 per day if needed, as long as there were enough rockets.

V2 Rocket Attacks

The V2 attacks began on September 7, 1944. Two rockets were launched at Paris, but both crashed. On September 8, a single rocket hit Paris, causing some damage. Later that day, a V2 was launched from The Hague against London. It landed in Chiswick, killing three people. Another hit Epping but caused no casualties.

The British government first tried to hide the cause of the explosions. They blamed them on faulty gas pipes. People didn't believe this and called the V2s "flying gas mains." The Germans finally announced the V2 on November 8, 1944. Only then, on November 10, did Winston Churchill tell the world that England had been under rocket attack.

In September 1944, the V2 mission was given to the Waffen-SS. German launch units moved around. For example, one unit moved to the Netherlands and launched V2s at Ipswich and Norwich. Because the rockets were not very accurate, they often missed these cities. Later, only London and Antwerp were targeted, as ordered by Adolf Hitler.

Main Targets of V2 Attacks

Over the following months, about 3,172 V2 rockets were fired at these targets:

- Belgium, 1,664 rockets: mostly Antwerp (1,610), with some hitting Liège, Hasselt, Tournai, Mons, and Diest.

- United Kingdom, 1,402 rockets: mostly London (1,358), with some hitting Norwich and Ipswich.

- France, 76 rockets: Lille, Paris, Tourcoing, Arras, and Cambrai.

- Netherlands, 19 rockets: all hit Maastricht.

- Germany, 11 rockets: all hit Remagen.

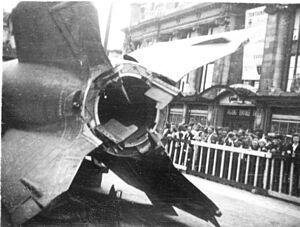

Antwerp was heavily attacked by V-weapons from October 1944 to March 1945. These attacks killed 1,736 people and injured 4,500. Thousands of buildings were damaged. The worst single attack happened on December 16, 1944, when a V2 hit a crowded movie theater, killing 567 people.

In London, about 2,754 civilians were killed by V2 attacks, and 6,523 were injured. This means about two people were killed per V2 rocket that hit. Many rockets missed their targets and exploded harmlessly. However, accuracy improved later in the war. One attack on November 25, 1944, killed 160 people at a Woolworth's department store in London.

British intelligence used a trick to make the Germans aim at the wrong place. They sent false reports saying the rockets were overshooting London. This worked, and more than half of the V2s aimed at London landed in less populated areas east of the city.

Final Attacks

The last two V2 rockets exploded on March 27, 1945. One of them killed Ivy Millichamp, a 34-year-old woman in Orpington, Kent. She was the last civilian killed by a V2 in Britain during the war. Scientists later found that a V2 creates a crater about 20 meters (65 feet) wide and 8 meters (26 feet) deep, throwing about 3,000 tons of material into the air.

Defending Against the V2

Unlike the V-1, the V2's speed and flight path made it almost impossible to stop with anti-aircraft guns or fighter planes. It dropped from very high altitudes at up to three times the speed of sound. Even so, efforts were made to find ways to counter this threat.

At first, people thought the V2 used radio guidance. So, they tried to jam these non-existent radio signals. But by December 1944, it was clear this wasn't working, and jamming efforts stopped.

General Frederick Alfred Pile, who commanded anti-aircraft guns, suggested firing many shells into the rocket's path. But this would require too many shells and cause more damage on the ground than the missile itself. So, this idea was rejected.

Pile later suggested a plan to fire fewer shells with new fuses that would reduce unexploded shells falling back to Earth. This might shoot down 1 in 50 rockets. However, they couldn't track the missiles accurately enough. By March 1945, tracking improved. A report suggested that firing 2,000 rounds at a missile would give a 1 in 60 chance of shooting it down. Plans for a test began, but the war ended before it could happen.

The only truly effective ways to defend against the V2 were to destroy its launch sites or to trick the Germans into aiming at the wrong place. The British successfully used disinformation to make the Germans aim V1s and V2s at less populated areas east of London.

Impact of the V2 Rocket

The German V-weapons (V-1 and V2) were very expensive. They cost about as much as the U.S. project that built the atomic bomb. About 6,048 V2s were built, and 3,225 were launched.

More people died making the V2 than were killed by its attacks. This was because SS General Hans Kammler used slave laborers from concentration camps to build the rockets.

The V2 used a lot of Germany's fuel alcohol production. To make the fuel for just one V2 launch, 30 tons of potatoes were needed. This was at a time when food was scarce. Sometimes, due to a lack of explosives, warheads were filled with concrete.

The V2 had a big psychological effect. Because it traveled faster than sound, it gave no warning before impact. There was no effective defense. The V2 did not change the outcome of World War II. However, it led to the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) during the Cold War. These rockets were also used for space exploration.

Post-War Use of V2 Technology

After the war, the United States and the USSR competed to get as many V2 rockets and German scientists as possible. The U.S. captured 300 train car loads of V2 parts. They also took 126 of the main designers, including Wernher von Braun. Von Braun and his team chose to surrender to the Americans to avoid being captured by the Soviets or killed by the Nazis.

German engineers were moved to the United States, the USSR, France, and the United Kingdom. There, they continued to develop the V2 rocket for military and peaceful uses. The V2 rocket laid the groundwork for liquid-fuel missiles and space launchers used later.

V2 Rockets in the United States

The U.S. brought the captured V2 parts to New Mexico. A committee of scientists was formed to decide what experiments to put on the reassembled V2 rockets. In January 1946, the U.S. Army invited scientists to use the V2 for space research. This led to many experiments that flew on V2s and helped prepare for American human space exploration. Instruments were sent up to measure air pressure, gases, and cosmic radiation.

On October 24, 1946, a V2 rocket took the first photo of Earth from space.

The PGM-11 Redstone rocket, which was important in early U.S. space efforts, is a direct descendant of the V2.

V2 Rockets in the Soviet Union

The USSR also captured V2s and German scientists. In October 1946, these scientists were moved to an island in Lake Seliger. There, Helmut Gröttrup led a group of 150 engineers. In October 1947, German scientists helped the USSR launch rebuilt V2s.

The first Soviet missile, the R-1, was a copy of the V2 made entirely in the USSR. It was launched in October 1948. The German team stayed on the island until 1952 and 1953. The Soviets then focused on building larger missiles based on V2 technology. Western countries did not know how advanced Soviet rockets were until the Sputnik 1 satellite was launched in November 1957. This satellite was launched by the Sputnik rocket, which was based on the R-7, the world's first intercontinental ballistic missile.

V2 Rockets in France

Between May and September 1946, France also hired about thirty German engineers who had worked on rockets for Nazi Germany. France wanted to get and improve the rocket technology developed by Germany. They had a plan called the "Super V-2" program for rockets that could fly very far. This program was canceled in 1948.

However, from 1950 to 1969, the research from the Super V-2 program was used to develop the Véronique rocket. This was the first liquid-fuel research rocket in Western Europe. It could carry a 100 kg (220 pound) payload to an altitude of 320 km (200 miles). The Véronique program then led to the Diamant rocket and the Ariane rocket family, which are important for European space launches today.

V2 Rockets in the UK

In October 1945, the Allies carried out "Operation Backfire." They put together a few V2 missiles and launched three of them from Germany. The engineers involved had already agreed to move to the U.S. after the tests. A report from this operation provided detailed technical information about the V2 rocket.

In 1946, the British Interplanetary Society suggested a larger version of the V2 that could carry a person. It was called Megaroc. This rocket could have allowed for sub-orbital spaceflight much earlier than it actually happened.

Surviving V2 Rockets and Parts

As of 2014, at least 20 V2 rockets still exist in various museums around the world.

Australia

- One V2 rocket and a complete Meillerwagen (transporter) are at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. This rocket has the most complete set of guidance parts of all surviving V2s.

Netherlands

- One V2, partly cut open to show its insides, is in the collection of the Nationaal Militair Museum. The museum also has a launch table and other parts.

Poland

- Several large parts, like the hydrogen peroxide tank, engine, and turbopump, are shown at the Polish Aviation Museum in Kraków.

- A rebuilt V2 missile with original parts is on display at the Armia Krajowa Museum in Kraków.

France

- One engine is at the Cité de l'espace in Toulouse.

- A V2 display with an engine, parts, and documents is at the La Coupole museum in Wizernes.

- One complete rocket is in the WWII section of the Musée de l'Armée in Paris.

Germany

- One complete V2 rocket and several engines are at the Deutsches Museum in Munich.

- One engine is at the German Museum of Technology in Berlin.

- One rusty engine is in the original V2 underground production facilities at the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp memorial site.

- A replica was built for the Historical and Technical Information Centre in Peenemünde.

United Kingdom

- One is at the Science Museum, London.

- One is at the Imperial War Museum, London.

- The RAF Museum has two rockets, one displayed at its Cosford site. The museum also owns a Meillerwagen and other support vehicles.

- One is at the Royal Engineers Museum in Chatham, Kent.

- A propulsion unit is in the Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum near Bungay.

- A complete turbo-pump is at the Solway Aviation Museum, Carlisle Airport.

United States

Complete missiles

- One is at the Flying Heritage Collection, Everett, Washington.

- One is at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Dayton, Ohio, including a complete Meillerwagen.

- One (painted in chessboard pattern) is at the Cosmosphere in Hutchinson, Kansas.

- One is at the National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C..

- One is at the Fort Bliss Air Defense Museum, El Paso, Texas.

- One (yellow and black) is at Missile Park, White Sands Missile Range in White Sands, New Mexico.

- One is at Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

- One is at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

Components

- One engine is at the Stafford Air & Space Museum in Weatherford, Oklahoma.

- One engine is at the U.S. Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

- Two engines are at the National Museum of the United States Air Force.

- Combustion chambers and other parts are at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Dulles, Virginia.

- One engine is at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago.

- One rocket body is at Picatinny Arsenal in Dover, New Jersey.

- One engine is in the Auburn University Engineering Laboratory.

- One engine is at the Exhibit Hall on the Historic Cape Canaveral Tour in Cape Canaveral, Florida.

- One engine is at Parks College of Engineering, Aviation and Technology in St. Louis, Missouri.

- One engine and tail section are at the New Mexico Museum of Space History in Alamogordo, New Mexico.

Images for kids

-

One of the victims of a V-2 that struck Teniers Square, Antwerp, Belgium, on 27 November 1944. A British military convoy was passing through the square at the time; 126 people (including 26 Allied soldiers) were killed.

-

Ruined buildings at Whitechapel, London, left by the penultimate V-2 to strike the city on 27 March 1945; the rocket killed 134 people. The final V-2 to fall on London killed one person at Orpington later that same day.

-

Rocket engine used by V-2, Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin (2014).

See also

In Spanish: Cohete V2 para niños

In Spanish: Cohete V2 para niños

- Gravity's Rainbow

- Wasserfall

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |