Operation Hydra (1943) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Operation Hydra |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Operation Crossbow | |||||||

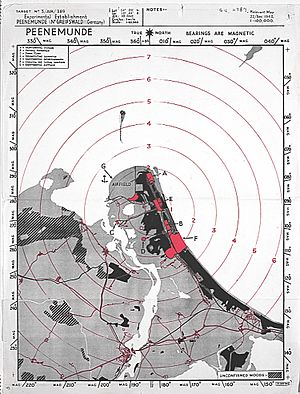

British plan for the Peenemünde raid |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

(5, 6, 8 groups) RAF Fighter Command |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John Searby (Master Bomber) | Josef Kammhuber Hubert Weise |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Hydra: 596 aircraft dispatched, 560 bombed 324 Avro Lancaster, 218 Handley Page Halifax, 54 Short Stirling 1,924 long tons (1,955 t) bombs (1,795 long tons (1,824 t) dropped), 85 per cent HE Whitebait: 8 Mosquitos Intruders: 28 Mosquitos, 10 Beaufighters |

Hydra: 35 night fighters inc. 2 Bf 109 c. 30 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 290: 245 killed, 45 POW Hydra: 23 Lancasters, 15 Halifaxes, 2 Stirlings |

12 aircrew killed, 12 aircraft lost: 8 Bf 110, 1 Do 217, 2 Fw 190, 1 Bf 109 c. 180 Germans, 500–732 slave workers 3 men and 1 convict labourer (by a bomb on Berlin) |

||||||

Operation Hydra was a major air attack by the British RAF Bomber Command. It targeted a German scientific research center at Peenemünde during the night of August 17–18, 1943. This operation was the first time the British used a "master bomber" to guide the main attack force. Group Captain John Searby led the mission.

Operation Hydra was the start of the Crossbow campaign. This campaign aimed to stop the German V-weapon program. The British lost 40 bombers and 215 aircrew. Sadly, several hundred enslaved workers in the nearby Trassenheide forced labor camp were also killed. The German Luftwaffe (air force) lost twelve night-fighters. About 170 German civilians died, including two important V-2 rocket scientists.

The attack delayed prototype V-2 rocket launches for about two months. It also forced Germany to spread out its rocket testing and production. The morale of the German survivors was badly affected. However, the overall impact of this operation on V-weapon production was later seen as "not effective" by a US report in 1945. The Germans had already started moving V-2 production in 1942.

Why the Attack Happened

German Rocket Research

After World War I, the Treaty of Versailles (1919) limited Germany's military. To get around these rules, the German army (the Reichswehr) looked into using rockets. They wanted rockets to make up for not having much heavy artillery.

In 1931, Captain Walter Dornberger joined the army's Ordnance Department. He was tasked with developing rockets. Dornberger led a team of scientists who worked on this new technology. They even got funding that could have gone to other research areas. Other scientists also explored rockets for things like sea rescue, weather, mail delivery, and even space travel.

British Intelligence Gathering

The British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), also known as MI6, had been getting information about German weapons since 1939. They received reports from various sources. These included Royal Air Force (RAF) photo-reconnaissance flights starting in April 1943. They also listened in on German prisoners of war. One prisoner, Lieutenant-General Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma, was surprised Britain hadn't been hit by rockets yet.

More information came from Polish intelligence and forced laborers from Luxembourg who worked at Peenemünde. These workers smuggled out letters describing rocket research. The details were sometimes confusing, but it was clear Germany was working on a rocket.

In April 1943, British military leaders were warned about possible rocket weapons. Duncan Sandys was asked by Prime Minister Winston Churchill to investigate. Sandys showed aerial photos of Peenemünde at a meeting. Some thought it was a trick, but others, like Reginald Victor Jones, believed the information was real. The committee suggested stopping spy flights to avoid alerting the Germans. Churchill decided that despite the challenges, they "must attack it on the heaviest possible scale."

On July 15, Churchill and his advisors approved the bombing plan. They ordered the attack to happen as soon as the moon and weather allowed.

Planning the Attack

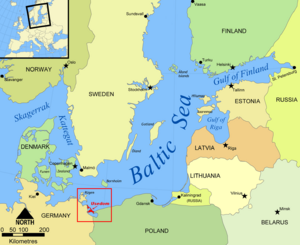

The raid needed to be very accurate, so it was planned for a night with a full moon. The bombers would fly lower than usual, at about 8,000 ft (2,400 m). Peenemünde was about 600 mi (1,000 km) from the nearest British airbase. It was also a large area and protected by smoke screens.

All of Bomber Command was to take part. They practiced bombing similar areas. At first, their bombs landed up to 1,000 yd (910 m) off target. But by the last practice, they were only 300 yd (270 m) off.

The main goal was to kill as many people working on the V-weapons as possible. This meant bombing the workers' living areas. Other goals were to destroy the research facility and all related V-weapon work and documents.

The pilots were not told the real target. They were told it was a radar development site that would improve German air defenses. To make sure aircrews tried their hardest, they were warned that if the attack failed, it would be repeated every night until it succeeded, no matter the losses.

Supporting Operations

Berlin Diversion

To pull German night fighters away from Peenemünde, eight Mosquito planes from No. 8 Group flew to Berlin. This was codenamed "Whitebait." They pretended to start a large bombing raid. The idea was that German night fighters would rush to Berlin, leaving Peenemünde less protected.

Attacking Airfields

Fighter Command sent 28 Mosquito and ten Beaufighter planes. Their job was to attack German airfields. They aimed to hit night fighters as they took off or landed. This would further reduce the number of German planes available to defend Peenemünde.

The Attack Begins

During the entire attack, the master bomber, Group Captain J. H. Searby, flew above the target. He guided the planes, telling them where to drop their bombs.

First Wave

The first wave of 244 British planes attacked the area where the V-2 scientists lived. The first target markers were dropped at 00:10 British time. Clouds and poor visibility made it hard to see. Some early markers landed on the Trassenheide forced labor camp by mistake.

Within three minutes, the master bomber saw a good marker for the scientists' homes. He ordered more markers there. About one-third of the planes in this wave bombed Trassenheide. This killed at least 500 enslaved workers. After that, the bombing shifted to the correct target. About 75 percent of the buildings were destroyed. However, only about 170 of the 4,000 people attacked were killed. This was because the soft ground lessened the bomb blasts. Also, the air raid shelters were well built. Sadly, Dr. Walter Thiel, the chief engineer for rocket motors, and Dr. Erich Walther, chief engineer of the rocket factory, were killed.

Second Wave

The second wave had 131 planes, mostly Lancasters. They aimed to destroy the V-2 rocket factory buildings. These buildings were about 300 yd (270 m) long. The planes carried many heavy bombs.

The pathfinders had to move their target markers from the first wave's targets to the new ones. This was a difficult task that had never been tried before. Some markers landed too far or too short. The master bomber warned the second wave to ignore the misplaced markers. The bombing hit a building used to store rockets, destroying its roof and contents. Strong winds blew some markers eastward, causing some bombs to land in the sea.

Third Wave

The third wave consisted of 117 Lancasters and 61 Halifax bombers. They attacked the experimental works. This area had about 70 small buildings. These buildings held scientific equipment, data, and the homes of important scientists like Dornberger and Wernher von Braun.

This wave arrived 30 minutes into the attack. Smoke from earlier bombings and German smoke screens covered the target. Also, German night-fighters, which had been diverted to Berlin, started to arrive. Some British bombs landed far off target, hitting a concentration camp. At 00:55, 35 planes were still waiting to bomb due to timing errors. The wind tunnel and telemetry block were missed. However, one-third of the buildings were hit, including the main headquarters. German night-fighters shot down 28 bombers in about 15 minutes. Some of these German planes used a new upward-firing weapon called Schräge Musik. The British bombers shot down five German fighters.

German Air Force Response

The Luftwaffe sent 213 night fighters once the British bombers reached Denmark. These included 158 twin-engined planes and 55 single-engined Wilde Sau (Wild Boar) fighters.

Aftermath

Casualties and Damage

At the Trassenheide labor camp, 23 of 45 huts were destroyed. At least 500, and possibly 600, enslaved workers died in the bombing. The British Bomber Command lost 6.7 percent of its planes. Most of these losses happened in the third wave.

After the Luftwaffe realized the Berlin attack was a trick, about 30 Wilde Sau night fighters flew to the Baltic coast. They shot down 29 of the 40 lost bombers. Fifteen British and Canadian airmen killed in the raid were buried by the Germans in unmarked graves. Their bodies could not be recovered after the war.

German Camouflage Efforts

After Operation Hydra, the Germans tried to hide the damage at Peenemünde. They made fake bomb craters in the sand. They also blew up lightly damaged or minor buildings. A scientist named Siegfried Winter said they painted black and white lines on roofs to make them look charred.

Operation Hydra also used bombs with timers set for up to three days. So, along with bombs that didn't explode right away, blasts continued well after the attack. This made German cleanup efforts harder.

See also

- Ludwig Crüwell

- Wilhelm Ritter von Thoma

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |