Operation Biting facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Operation Biting |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the British raids during the Second World War | |||||||

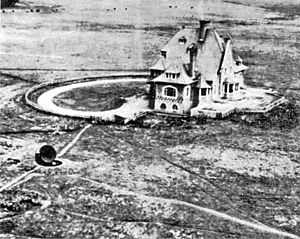

Bruneval photographed in December 1941 by the RAF, with its Würzburg radar at left |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John Frost | Unknown | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~130 men | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

||||||

Operation Biting, also called the Bruneval Raid, was a secret mission by British forces during Second World War. On the night of 27–28 February 1942, a special team raided a German radar station in Bruneval, France. The goal was to steal important radar parts and learn how the German technology worked.

British scientists had seen these radar stations in Royal Air Force (RAF) photos. They thought these stations were helping German planes find and shoot down British bombers. So, they asked for a raid to get the radar equipment for study.

The Germans had strong defenses along the coast. This made a sea attack too risky. So, the British decided to use paratroopers to surprise the Germans. After grabbing the radar, the paratroopers would be picked up by boats. This plan aimed to get the technology quickly and keep British casualties low.

On the night of February 27, 1942, after lots of training, a group of paratroopers led by Major John Frost jumped into France. They landed near the radar station. The main group attacked the building where the radar was kept. They fought briefly, took over the station, and captured some German soldiers.

An RAF technician with the team carefully took apart the Würzburg radar and removed key pieces. Then, the team headed to the beach for evacuation. The group meant to secure the beach had trouble at first. But with help from the main force, they cleared the German guards. British landing craft picked up the troops, who then moved to motor gunboats and returned to Britain.

The raid was a big success. The paratroopers had few casualties. The radar parts and a captured German technician helped British scientists understand German radar. This allowed them to create ways to trick the enemy's radar.

Contents

Why the Raid Was Needed

After the Battle of France, Britain focused on bombing Germany. But British bomber planes started getting shot down more often in 1941. British spies thought this was because Germany had advanced radar.

Britain and Germany had been working on radar for almost ten years. German radar technology was often as good as, or even better than, Britain's. By the start of World War II, Britain had good radar systems. But they didn't have a good system to defend against German night bombings in 1940.

R. V. Jones was a British scientist who studied radar. He was Britain's first scientific intelligence officer. He spent years figuring out how advanced German radar was. He even convinced others that Germany really did have radar.

Jones found out that strong radio signals were coming from Europe into Britain. He believed they were from a special radar system. He soon found several such systems. One was called "Freya-Meldung-Freya". It was used to find British bombers. Jones finally saw proof of the Freya system in RAF photos. These photos showed two round areas with large, rotating antennas. Once they knew about Freya, Jones and his team could start working on ways to counter it. The RAF could also find and destroy these stations.

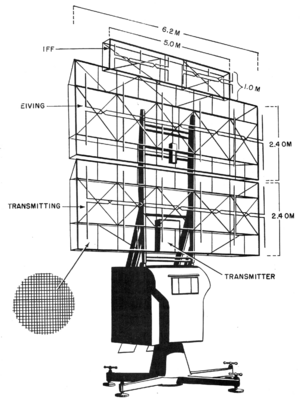

Jones also found clues about another German radar system called "Würzburg". In November 1941, new RAF photos showed what Würzburg looked like. It had a dish-shaped antenna about 10 feet (3 meters) wide. Würzburg worked with Freya. Freya found British bombers from far away, but wasn't very precise. Würzburg had a shorter range but was much more accurate. It helped German night fighters find and attack British bombers. The Würzburg system was also smaller and easier to build.

Planning the Secret Mission

To beat the Würzburg system, Jones and his team needed to study one. An RAF reconnaissance Spitfire found a Würzburg site on a cliff near Bruneval, France. This site was the easiest to reach.

The request for a raid on Bruneval went to Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. He was the commander of Combined Operations. Mountbatten took the idea to the military leaders, who approved the raid.

Mountbatten and his team studied the Bruneval site. They saw that the German defenses were too strong for a sea attack. Such an attack would cause many casualties and might not be fast enough to get the radar before it was destroyed. Mountbatten believed that surprise and speed were key. So, he decided an airborne attack was the only way.

On January 8, 1942, he asked the 1st Airborne Division and 38 Wing RAF if they could do the raid. The division's commander, Major-General Frederick Browning, was very excited. A successful mission would boost morale for his paratroopers and show their value.

Training for the raid started right away. No. 51 Squadron RAF was chosen to provide the planes and aircrews. The 2nd Parachute Battalion was chosen for the raid. Major Frost's 'C' Company was picked, even though many of them had not finished their parachute training yet.

The mission was kept very secret. Major Frost was first told his company was doing a demonstration for the government. He only learned about the real raid later. Then, he focused on training his company.

Training for the Raid

The company trained in Salisbury Plain and then in Scotland. In Scotland, they practiced getting onto landing craft at night. This prepared them for being picked up by sea after the raid. Then, they returned to Salisbury Plain to practice parachute jumps with 51 Squadron.

The aircrews had never dropped paratroopers before, but the training went well. A detailed model of the radar station was built to help the company plan. Major Frost met Commander F. N. Cook of the Royal Australian Navy, who would command the naval force. He also met thirty-two men from No. 12 Commando who would help cover the withdrawal from the beach.

Frost also met RAF Flight Sergeant C.W.H. Cox. Cox was a radio expert who volunteered for the mission. His job was to find the Würzburg radar, photograph it, and take it apart. A 10-man team of Royal Engineers also joined. Six of them would dismantle the radar, and four would plant anti-tank mines to protect the team.

Information about the Bruneval radar station was gathered with help from the French Resistance. This group, led by Gilbert Renault (code-name 'Rémy'), provided key details about the German forces.

The radar station had two main parts. A villa about 100 yards (91 m) from the cliff held the radar equipment. A nearby area had smaller buildings with about 100 German troops. The Würzburg antenna was between the villa and the cliff. About 30 guards were always at the radar station. A German infantry platoon was in Bruneval to the south. They guarded the evacuation beach with a strongpoint, pillboxes, and machine gun nests. The beach had some barbed wire but no landmines.

Based on this, Frost divided his company into five groups: 'Nelson', 'Jellicoe', 'Hardy', 'Drake', and 'Rodney'.

- 'Nelson' would clear the beach defenses.

- 'Jellicoe', 'Hardy', and 'Drake' would capture the radar site and villa.

- 'Rodney' was the reserve group, ready to stop any German counterattack.

The raid needed a full moon for light and a rising tide for the boats. This limited the possible dates to February 24-27. A final practice on February 23 failed because the landing craft got stuck far from shore.

The Raid

The raid was delayed a few days due to bad weather. But on February 27, the weather was perfect. The sky was clear for the planes, and a full moon would light up the evacuation. The naval force left Britain in the afternoon. The Whitley planes carrying the paratroopers took off from RAF Thruxton in the evening.

The planes crossed the English Channel safely. As they reached France, they faced heavy anti-aircraft fire, but none were hit. They successfully dropped the paratroopers near the radar station. Most of the troops landed correctly. However, half of the 'Nelson' group landed two miles short. Once the groups gathered their gear, they moved to their targets.

'Jellicoe', 'Hardy', and 'Drake' met no resistance as they moved to the villa. Frost ordered them to open fire. One German guard was killed, and two were captured. The prisoners said most of the German soldiers were further inland. But a group of Germans in nearby buildings opened fire, killing one paratrooper.

More enemy fire started, and vehicles were seen moving towards the villa. Frost was worried because his radios weren't working. He couldn't talk to 'Nelson', who were supposed to secure the beach. Flight Sergeant Cox and some engineers arrived and began taking apart the radar. They put the pieces on special trolleys.

With the radar parts secured and under heavy enemy fire, Major Frost ordered the three groups to withdraw to the beach. But the beach wasn't secure. A German machine gun opened fire, badly wounding the company sergeant major. Frost ordered 'Rodney' and the available 'Nelson' men to clear the defenses. He led the other three groups back to the villa, which Germans had reoccupied.

The villa was quickly cleared again. When Frost returned to the beach, the machine-gun nest was destroyed. The 'Nelson' troops who had landed in the wrong spot had reached the beach and attacked the machine gun from the side. It was 2:15 AM, but there was no sign of the naval force. Frost ordered 'Nelson' to guard the land approaches and then fired an emergency signal flare. Soon after, the boats appeared.

The original plan was for two landing craft to land at a time. But all six landed at once. The troops on the boats fired at German soldiers gathering on the cliff. This caused some confusion. Some boats left overcrowded, others half-empty. But the radar equipment, German prisoners, and all but six of the paratroopers got on board. They were transferred to motor gunboats for the trip back to Britain. On the way back, Frost learned the naval force had only seen his flare. They had spent time hiding from a German naval patrol. The journey back was calm, with four destroyers and Spitfires escorting them.

The paratroopers lost two killed, eight wounded, and six captured. German reports later showed their losses were five killed, two wounded, and three missing. A French Resistance member who helped with the raid was captured and executed. A French couple who helped surviving paratroopers were sent to concentration camps.

What Happened Next

The success of the Bruneval raid had two big effects. First, it was a great morale boost for the British public. It was in the news for weeks. British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, was very interested. On March 3, he met with Major Frost and other officers from the raid. Many medals were given out.

On May 15, 1942, 19 awards were announced. Frost received the Military Cross, Cook the Distinguished Service Cross, and Cox the Military Medal. The success of the raid also led the War Office to expand British airborne forces. They created the Airborne Forces Depot and Battle School in April 1942. They also formed the Parachute Regiment and turned other infantry battalions into airborne battalions in August 1942.

The second and most important result was the technical knowledge British scientists gained. They found that the radar was built in a modular way. This made it easy to fix. The captured German technician confirmed this.

Studying the radar also showed British scientists that they needed to use a new countermeasure called Window. The Würzburg radar could not be jammed by older British methods. So, Window had to be used. Window's effectiveness against Würzburg radar was proven in a raid on Hamburg on July 24, 1943 (Operation Gomorrah). The bombers used Window, which blinded the radar and confused the German operators.

- Aftermath

-

Flak pointing system captured at Bruneval and now on display at the Musée de l'Armée in Paris

An unexpected benefit of the raid was that Germans tried to improve defenses at other Würzburg stations. They surrounded the radars with barbed wire. This made them easier to spot from the air, which helped later in the war before Operation Overlord. The Telecommunications Research Establishment, where the Bruneval equipment was studied, was moved further inland to Malvern. This was to protect it from any German revenge raids. The original model of the radar station, used to brief the troops, is now in the Parachute Regiment and Airborne Forces Museum.

See also

- Radar in World War II

| James Van Der Zee |

| Alma Thomas |

| Ellis Wilson |

| Margaret Taylor-Burroughs |