Philip Morrison facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Philip Morrison

|

|

|---|---|

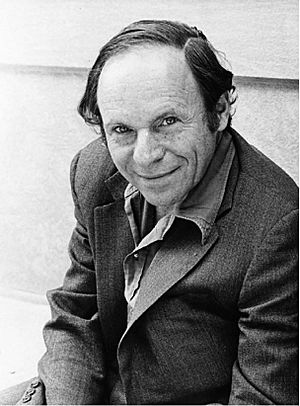

Morrison in 1976

|

|

| Born | November 7, 1915 Somerville, New Jersey, U.S.

|

| Died | April 22, 2005 (aged 89) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S.

|

| Nationality | United States |

| Alma mater | Carnegie Tech University of California, Berkeley |

| Known for | SETI, science education |

| Spouse(s) |

Emily Kramer

(m. 1938; div. 1961)Phylis Hagen

(m. 1965; died 2002) |

| Awards | Babson Prize of the Gravity Foundation Westinghouse Science Writing Award of the American Association for the Advancement of Science |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astrophysics |

| Institutions | San Francisco State University University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign Manhattan Project Cornell University Massachusetts Institute of Technology |

| Thesis | Three Problems in Atomic Electrodynamics (1940) |

| Doctoral advisor | J. Robert Oppenheimer |

| Signature | |

Philip Morrison (born November 7, 1915 – died April 22, 2005) was a smart American professor of physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He is famous for his work on the Manhattan Project during World War II, where he helped create the first atomic bombs. Later, he became known for his research in quantum physics (the study of tiny particles), nuclear physics, and astrophysics (the study of stars and space).

Morrison studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley, under the famous scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer. During World War II, he joined the Manhattan Project at the University of Chicago. There, he worked on designing nuclear reactors, which are machines that create nuclear energy.

In 1944, he moved to the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico. Here, he helped develop special explosives needed to make the atomic bomb work. He even transported the core of the first atomic bomb (for the Trinity test) in a car. He also helped load the atomic bombs onto the planes that dropped them on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. After the war, he visited Hiroshima to see the damage.

After the war, Philip Morrison became a strong supporter of nuclear nonproliferation. This means he worked to stop the spread of nuclear weapons around the world. He wrote articles and helped start groups like the Federation of American Scientists. Even though he faced challenges because of his past political beliefs, he continued his important work. He shifted his research from nuclear physics to studying space. He wrote about cosmic rays (energy particles from space) and helped start the field of gamma ray astronomy, which studies high-energy light from space. He also loved to share science with everyone through books and TV shows.

Contents

Early Life and School

Philip Morrison was born in Somerville, New Jersey, on November 7, 1915. He was the only son of Moses and Tillie Morrison and had a younger sister named Gail. When he was two, his family moved to Pittsburgh. At age four, he got polio, a disease that affected his leg. Because of this, he wore a special brace and later used a wheelchair. He started school a bit later than other kids, in the third grade.

After high school, he went to Carnegie Tech, planning to study electrical engineering. But he soon became very interested in physics. He earned his first degree in 1936. Then, he went to the University of California, Berkeley, where he earned his PhD (a very advanced degree) in theoretical physics in 1940. His teacher was J. Robert Oppenheimer.

In 1938, Morrison married Emily Kramer, who he knew from high school. They later divorced in 1961. In 1965, he married Phylis Hagen, and they stayed together until she passed away in 2002.

Working on the Manhattan Project

After getting his PhD, Philip Morrison taught at San Francisco State University and then at the University of Illinois. In December 1942, during World War II, he was asked to join the Manhattan Project. This was a top-secret project to build the first atomic bomb. He started working at the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago in January 1943. There, he helped Eugene Wigner design nuclear reactors.

Morrison was worried about Germany developing its own nuclear weapons. He helped convince the head of the Manhattan Project, General Leslie R. Groves, Jr., to start the Alsos Mission. This mission aimed to gather information on Germany's nuclear program.

In mid-1944, Morrison moved to the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico. He became a group leader there. His first job was to figure out how much plutonium was needed for a bomb. He calculated that about 6 kilograms would be enough. He then worked with George Kistiakowsky on the special explosives needed to make the implosion-type nuclear weapon explode.

Morrison personally transported the core of the first atomic bomb, used in the Trinity test, in the back seat of a car. He watched the test on July 16, 1945, and wrote a report about it. A month later, he led a team that helped load the atomic bombs onto the planes. These planes then carried out the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. After the war, Morrison and Robert Serber went to Hiroshima to see how much damage the bomb had caused.

Becoming an Activist

After the war, Morrison returned to Los Alamos and stayed there until 1946. He decided not to go back to Berkeley and instead joined the physics department at Cornell University.

Seeing the terrible destruction in Hiroshima made Morrison a strong supporter of nuclear nonproliferation. This means he worked to prevent other countries from getting nuclear weapons. He wrote for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and helped create groups like the Federation of American Scientists. He spoke to Congress about the need for civilians, not just the military, to control nuclear energy. He also took part in civil rights events. In 1949, a magazine called Life even featured him in a list of "America's 50 most eminent dupes and fellow travellers" because of his political views.

Morrison had joined the Communist Party USA when he was at Berkeley. In the 1950s, during a time of strong anti-communist feelings in the U.S., he faced pressure. He was questioned by government committees. The president of Cornell University was urged to fire him. However, his colleagues, like Hans Bethe, supported him. They said he had shown his loyalty by helping develop the atomic bomb during the war.

Morrison agreed to focus only on his academic work in 1954. He was one of the few former communists who kept their jobs and stayed active in science during the 1950s. In 1999, a writer wrongly accused Morrison of being a spy, but Morrison strongly proved this was false, and the writer accepted his explanation.

His Work in Science

In 1940, Morrison worked with Leonard I. Schiff on a paper about gamma rays. After the war, at Cornell, he continued to work in nuclear physics. He even wrote a textbook with Hans Bethe called Elementary Nuclear Theory (1952).

As his political views changed, Morrison became more interested in space. In 1954, he published a paper with Bruno Rossi and Stanislaw Olbert. They looked at Enrico Fermi's idea of how cosmic rays travel through our galaxy. Morrison then reviewed different ideas about where cosmic rays come from in 1957. A paper he wrote in 1958 is seen as the start of gamma ray astronomy, which studies the universe using gamma rays.

In 1959, Morrison worked with Giuseppe Cocconi on a paper. They suggested that microwaves could be used to search for messages from aliens. This was one of the first ideas for the modern SETI program. He believed that "The chance of success is hard to guess, but if we never look, the chance of success is zero."

Morrison stayed at Cornell until 1964. Then, he moved to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He worked there for the rest of his career, becoming a top professor. At MIT, he joined teams studying x-rays and gamma rays from space. He became very involved in exploring the cosmos by looking at these high-energy emissions. In 1960, he noticed how similar pulsars and quasars were. He continued this work in 1976, applying his ideas to a radio galaxy called Cygnus A.

Sharing Science with Everyone

Philip Morrison was well-known for his many books and TV shows. He wrote 68 popular science articles between 1949 and 1976, with ten appearing in Scientific American magazine. He wrote the script and narrated the famous film Powers of Ten in 1977. With his wife, Phylis, he turned the film's ideas into a book in 1982. He also appeared in the science documentary film Target...Earth? in 1980. In 1987, PBS aired his six-part TV series, The Ring of Truth: An Inquiry into How We Know What We Know, which he also hosted. From 1965, he wrote columns and reviewed science books for Scientific American.

Later in his life, he spoke out against the Strategic Defense Initiative, a missile defense system. He wrote several books that were critical of the Cold War and the nuclear arms race. These books included Winding Down: The Price of Defense (1979) and The Nuclear Almanac (1984).

Awards and Honors

Philip Morrison was a member of many important scientific groups, including the American Physical Society and the National Academy of Sciences. He was also the chairman of the Federation of American Scientists from 1973 to 1976.

Throughout his life, Morrison received many awards. He gave special lectures, like the 1968 Royal Institution Christmas Lectures about the physics of large and small things. He also received the Presidential Award from the New York Academy of Sciences, the Westinghouse Science Writing Award, and the Oersted Medal for teaching physics. He and his wife Phylis also received the Wheeler Prize from the Boston Museum of Science.

Death

Philip Morrison passed away peacefully in his sleep from breathing problems at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on April 22, 2005. He was survived by his stepson, Bert Singer.

See also

In Spanish: Philip Morrison para niños

In Spanish: Philip Morrison para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |