James Chadwick facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

James Chadwick

|

|

|---|---|

Chadwick c. 1945

|

|

| Born | 20 October 1891 Bollington, Cheshire, England

|

| Died | 24 July 1974 (aged 82) Cambridge, England

|

| Alma mater | |

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions |

|

| Doctoral advisor | Ernest Rutherford |

| Doctoral students |

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Sir James Chadwick (born October 20, 1891 – died July 24, 1974) was an English physicist. He won the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for discovering the neutron in 1932. This discovery was a huge step in understanding how atoms work.

Later, in 1941, he helped write an important report called the MAUD Report. This report encouraged the U.S. government to start serious research into building an atom bomb. During World War II, he led the British team that worked on the Manhattan Project. He was made a knight in Britain in 1945 because of his important work in physics.

Contents

Early Life and Education

James Chadwick was born in Bollington, England, on October 20, 1891. He was the first child of John Joseph Chadwick and Anne Mary Knowles. When he was four, his parents moved to Manchester, and he stayed with his grandparents.

He later joined his parents in Manchester and attended the Central Grammar School for Boys. At 16, he won two university scholarships.

Studying Physics

In 1908, Chadwick chose to attend Victoria University of Manchester. He actually meant to study math but accidentally enrolled in physics. The physics department was led by Ernest Rutherford, who is known as the "father of nuclear physics."

Rutherford gave Chadwick a research project to compare the energy of different radioactive sources. Chadwick found a way to do this, and his results became his first published paper in 1912. He graduated with top honors in 1911.

After this, Chadwick measured how gamma rays were absorbed by different materials. He earned his Master of Science (MSc) degree in 1912. The next year, he received a scholarship to study in Europe.

Research in Germany

In 1913, Chadwick went to Berlin, Germany, to study beta radiation under Hans Geiger. Geiger had recently invented the Geiger counter, which was much more accurate than older methods.

Using this new tool, Chadwick showed that beta radiation produced a continuous range of energies, not just specific lines as people had thought. This was a puzzling discovery at the time.

World War I Internment

Chadwick was still in Germany when World War I started. He was held in the Ruhleben internment camp near Berlin for four years. Even there, he managed to set up a small lab in the stables. He did experiments using materials he found, like radioactive toothpaste.

After the war ended in November 1918, he returned to Manchester. He wrote down all his findings from his time in the camp.

Joining Rutherford in Cambridge

Rutherford offered Chadwick a part-time teaching job in Manchester. In April 1919, Rutherford moved to the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge, and Chadwick joined him a few months later.

Chadwick started his PhD at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. His research focused on the number of charges in an atom's center and the forces inside the atomic nucleus. He received his PhD in June 1921.

Discovering the Neutron

In 1923, Chadwick became Rutherford's assistant director of research at the Cavendish Laboratory. He helped Rutherford choose PhD students, including future famous scientists like John Cockcroft and Mark Oliphant. Chadwick also edited all the scientific papers from the lab.

In 1925, Chadwick married Aileen Stewart-Brown. They had twin daughters, Joanna and Judith, in 1927.

The Search for a New Particle

Scientists at the time believed that the center of an atom (the nucleus) was made of protons and electrons. However, this idea didn't explain everything, especially the "spin" of some atoms.

In 1928, Chadwick met Hans Geiger again. Geiger had a new and improved Geiger counter. This new device was much better for detecting radiation. Chadwick realized he could use a special element called polonium, which only gives off alpha particles, for his experiments.

In Germany, scientists Walther Bothe and Herbert Becker had bombarded beryllium with alpha particles. They noticed a strange new kind of radiation. Chadwick thought this might be a new particle he and Rutherford had been thinking about: the neutron. A neutron would be a particle inside the nucleus with no electric charge.

Then, in January 1932, other scientists, Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie, found that this radiation could knock protons out of paraffin wax. Rutherford and Chadwick knew that protons were too heavy to be moved by gamma rays. But if the radiation was made of neutrons, it would make sense.

Proving the Neutron Exists

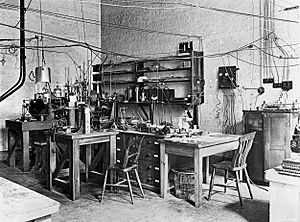

Chadwick stopped all his other work to focus on proving the neutron existed. He designed a simple experiment. He used a cylinder with a polonium source and a beryllium target. The radiation from this setup was directed at materials like paraffin wax. The particles knocked out of the wax were protons, which he detected with an oscilloscope.

In February 1932, after only two weeks, Chadwick sent a letter to Nature titled "Possible Existence of a Neutron." He then published a more detailed paper in May. His discovery of the neutron was a major breakthrough in understanding the atom's nucleus.

Scientists soon realized that if the neutron had a certain "spin," it would solve many puzzles about atoms. The neutron was a new kind of nuclear particle, not just a proton and electron stuck together.

Measuring the Neutron's Mass

Chadwick and his student Maurice Goldhaber found a way to measure the neutron's mass accurately. They used gamma rays to break apart deuterons (heavy hydrogen atoms). By measuring the energy of the pieces, they could calculate the neutron's mass. They found it was too heavy to be a proton-electron pair.

For his discovery, Chadwick received many awards, including the Hughes Medal in 1932 and the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1935. The neutron's discovery made it possible to create new, heavier elements in the lab. Neutrons, unlike charged particles, can easily enter the nucleus of other atoms. This led Enrico Fermi to study reactions with slow neutrons, which earned him a Nobel Prize.

The Neutrino

In 1930, Wolfgang Pauli suggested another particle to explain why some beta radiation seemed to lose energy. He called it a "neutron," but it was different from Chadwick's neutron. Enrico Fermi later renamed it the neutrino, meaning "little neutron."

In 1934, Fermi proposed that electrons are released when a neutron breaks down into a proton, an electron, and a neutrino. Neutrinos were very hard to detect because they have little mass and no charge. Scientists finally confirmed the neutrino's existence in 1956.

Professor at Liverpool

In the 1930s, funding for science became harder to get. Chadwick felt that the Cavendish Laboratory needed a cyclotron, a new machine that could speed up particles. But Rutherford didn't think such expensive equipment was necessary.

In March 1935, Chadwick was offered a physics professor position at the University of Liverpool. He took the job on October 1, 1935. The university's reputation grew quickly when Chadwick won the Nobel Prize that November.

Chadwick immediately started working to get a cyclotron for Liverpool. He raised money from the university and the Royal Society. He also brought in experts to help build it. The cyclotron was finished and running by July 1939. Chadwick even paid some of the costs himself using his Nobel Prize money.

At Liverpool, Chadwick believed that neutrons and radioactive materials made by the cyclotron could help study how living things work. He also thought they could be used to fight cancer.

World War II and the Atom Bomb

In Germany, scientists discovered nuclear fission in 1939. This meant that uranium atoms could split apart when hit by neutrons, releasing a huge amount of energy. They also realized that if more neutrons were released, a chain reaction could happen.

Chadwick did not expect another war in 1939. He was on holiday in Sweden when World War II began. He quickly returned to England, determined not to be interned again.

The MAUD Report

In October 1939, Chadwick was asked if an atom bomb was possible. He was cautious but didn't rule it out. He studied uranium oxide further with his colleague Joseph Rotblat.

In March 1940, other scientists, Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls, calculated that a small amount of pure uranium-235 could create a powerful chain reaction. This became known as the Frisch–Peierls memorandum.

A special committee, the MAUD Committee, was formed to investigate this. Chadwick's team at Liverpool worked to figure out how much uranium-235 would be needed for a bomb. By April 1941, they confirmed that a very small amount, perhaps 8 kilograms or less, could work.

Chadwick's research was difficult because his lab in Liverpool was often bombed by the Luftwaffe. The windows were blown out so many times that they were replaced with cardboard.

In July 1941, Chadwick wrote the final version of the MAUD Report. This report was given to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in October 1941. It convinced the U.S. government to invest millions of dollars into building an atom bomb. Chadwick later said he realized that a nuclear bomb was "not only possible—it was inevitable."

The Manhattan Project

Because of the danger from air raids, the Chadwicks sent their twin daughters to Canada for safety. Building an atom bomb plant in Britain seemed too difficult during wartime. It would be very expensive and hard to hide from enemy planes. So, it was decided that the main project would be in America.

In September 1943, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and President Roosevelt agreed to work together again on the project. This agreement was called the Quebec Agreement. Chadwick was appointed the technical advisor for the joint project and the head of the British team.

Chadwick toured the American facilities in November 1943. He was the only person besides the project director, Leslie R. Groves, Jr., who had access to almost all the American research and production sites for the uranium bomb. He saw how huge the K-25 plant was in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and realized it could never have been hidden in Britain.

In early 1944, Chadwick moved to Los Alamos, New Mexico, with his family. For security, he used the cover name James Chaffee. Chadwick worked closely with General Groves. He tried to place British scientists in as many parts of the project as possible. This was to help Britain develop its own nuclear weapons after the war. The British team was very important to the project's success.

For his efforts, Chadwick was knighted on January 1, 1945. He saw this as an honor for the entire British project.

By early 1945, Chadwick spent most of his time in Washington, D.C. He was present at the meeting on July 4 when Britain agreed to use the atom bomb against Japan. He also witnessed the Trinity nuclear test on July 16, when the first atom bomb was exploded. The bomb used a special part called a "modulated neutron initiator," which was based on the technique Chadwick had used to discover the neutron years before.

Later Life and Legacy

After the war, Chadwick became a scientific advisor to the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission. He believed Britain needed its own nuclear weapons, a view that was eventually adopted. He returned to Britain in 1946.

His colleagues noted that Chadwick was very tired, both physically and mentally, from the huge responsibilities of his wartime work. He had faced difficult moral decisions.

In 1948, Chadwick became the Master of Gonville and Caius College at Cambridge. He worked to improve the college's academic reputation by increasing research positions and bringing in talented people. He retired in 1959. During his time as Master, Francis Crick and James Watson discovered the structure of DNA at the college.

Chadwick received many honors throughout his life, including the Medal for Merit from the United States. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1927. In 1970, he was made a Companion of Honour for his contributions to science.

He became more frail in his later years and died in his sleep on July 24, 1974.

Chadwick's papers are kept at the Churchill Archives Centre in Cambridge. The Chadwick Laboratory at the University of Liverpool is named after him, as is a special physics professorship. A crater on the Moon is also named in his honor. The James Chadwick Building at the School of Chemical Engineering and Analytical Sciences, University of Manchester also bears his name. He is remembered as a wise and humane scientist who played a key role in understanding the atom.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: James Chadwick para niños

In Spanish: James Chadwick para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |