Quebec Agreement facts for kids

| Articles of Agreement Governing Collaboration Between the Authorities of the U.S.A. and U.K. in the Matter of Tube Alloys | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Signed | 19 August 1943 |

| Location | Quebec City, Quebec, Canada |

| Effective | 19 August 1943 |

| Expiration | 7 January 1948 |

| Signatories |

|

The Quebec Agreement was a secret deal between the United Kingdom and the United States during World War II. It set out the rules for how they would work together to develop nuclear energy and, more specifically, nuclear weapons. Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister of the UK, and Franklin D. Roosevelt, the President of the US, signed it on August 19, 1943. This happened during the First Quebec Conference in Quebec City, Canada.

The agreement said that the US and UK would combine their efforts to build nuclear weapons. It also stated that neither country would use these weapons against the other, or against any other country without both agreeing first. They also promised not to share information about these weapons with other countries without mutual consent. The agreement also gave the United States the power to say "no" to Britain using nuclear energy for business or industry after the war. This agreement brought together Britain's secret Tube Alloys project and America's Manhattan Project. They also created a group called the Combined Policy Committee to manage the joint effort. Even though Canada didn't sign the agreement, it got a spot on this committee because of its help.

British scientists played a big part in the British contribution to the Manhattan Project. In July 1945, Britain gave its permission, as required by the agreement, for the US to use nuclear weapons against Japan. A later agreement in September 1944, called the Hyde Park Aide-Mémoire, aimed to continue this teamwork after the war. However, after the war ended, the US became less interested in working closely with Britain. A law called the McMahon Act (1946) stopped the sharing of technical information. On January 7, 1948, the Quebec Agreement was replaced by a new understanding, a modus vivendi, which allowed for some limited sharing of technical information among the United States, Britain, and Canada.

Contents

How the Project Started

Britain's Secret Atomic Work

The idea of an atomic bomb began with scientific discoveries. In 1932, James Chadwick discovered the neutron. Later, in 1938, scientists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann found that they could split uranium atoms. This process was called "fission". This discovery made scientists wonder if a super powerful atomic bomb could be made.

In 1939, just before World War II began, a British committee started looking into atomic bombs. At first, experiments didn't go well. But then, two German refugee scientists, Rudolf Peierls and Otto Frisch, made a huge discovery. They calculated that a very small amount of a special type of uranium, called uranium-235, could create a massive explosion. This was much less than what everyone had thought.

This finding led to the creation of the MAUD Committee in Britain. This committee pushed for more research. Scientists at four universities worked on different parts of the problem:

- The University of Birmingham worked on the theory, like figuring out how much uranium was needed for a bomb.

- The University of Liverpool and the University of Oxford looked into ways to separate different types of uranium. This was important because only uranium-235 could be used for a bomb.

- The University of Cambridge explored if another element, now known as plutonium, could also be used.

By July 1941, the MAUD Committee reported that an atomic bomb was possible and could be built quickly. They urged the government to develop it fast. Prime Minister Winston Churchill agreed. A new secret project, misleadingly named Tube Alloys, was set up to manage this effort.

Early American Efforts

Scientists in the United States were also worried that Germany might develop an atomic bomb. In 1939, Leo Szilard and Albert Einstein wrote a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, warning him about this danger. Roosevelt then created a committee to study uranium.

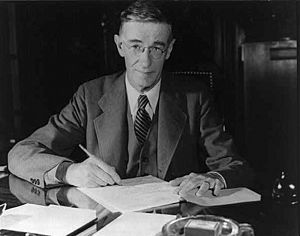

In 1940, Vannevar Bush helped create the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) to organize defense research. This group took over the uranium studies. Bush quickly arranged for the US and Britain to share scientific information.

British scientists shared their findings, including the MAUD Committee's reports. They noticed that the American atomic bomb project was moving slower than theirs. American scientists were working on things like creating a controlled nuclear chain reaction and separating uranium.

In 1941, a British scientist, Mark Oliphant, visited the US. He was upset that the Americans weren't taking the MAUD Committee's findings seriously. He found that important reports were locked away. Oliphant met with key American scientists and forcefully explained that they must focus on building the bomb. He said Britain couldn't afford it, so it was up to the US.

After hearing this, President Roosevelt decided to expand and speed up the American atomic bomb project. He wrote to Churchill, suggesting they work together.

Working Together

Roosevelt wanted to work closely with Britain, but Churchill's response was delayed. Britain had concerns about security and what would happen after the war. Because of this, the chance for a truly joint project was missed at first. Both countries continued to share information, but their projects remained separate.

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the United States entered the war. This meant a lot more money became available for the atomic project. In June 1942, the US Army was put in charge of its part of the project. Colonel James C. Marshall set up headquarters in New York City, calling it the Manhattan Engineer District. Soon, the whole project became known as the Manhattan Project. In September 1942, Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves, Jr. took over as director. Groves tried to keep information very secret, sharing it only on a "need-to-know" basis.

The American project quickly grew much larger than the British one. British scientists visiting the US in 1942 were amazed by the progress. British officials realized their early lead was shrinking. However, American officials, especially Bush and Conant, decided that British help was no longer needed. They worried that British companies might use American nuclear secrets for profit after the war.

In December 1942, President Roosevelt agreed to limit the information shared with Britain. The Americans stopped sharing details about how to make heavy water, separate uranium, or create plutonium. This hurt the British and Canadian project in Montreal, which was trying to design nuclear reactors. In response, the British stopped sending their scientists to the US, which slowed down some American work. Eventually, all information sharing stopped.

Britain then considered building a bomb on its own. But it would be very expensive and take too long, likely not being ready before the war in Europe ended. So, they decided to try again to get American cooperation. By March 1943, Bush and Conant realized that British scientists, like James Chadwick, could still help the Manhattan Project.

Making the Agreement

Churchill brought up the issue with Roosevelt when they met in Washington in May 1943. They agreed that the atomic bomb project should be a joint effort again. However, American policy didn't change right away because Roosevelt didn't tell Bush. Churchill kept pushing for action.

In July 1943, Bush met Churchill in London. Churchill told Bush that Roosevelt had promised full cooperation and was angry about the delays. Bush suggested Churchill talk to Henry L. Stimson, the US Secretary of War, who was also in London. Churchill did, and Stimson promised to discuss it with Roosevelt. Roosevelt then instructed Bush to restart the full exchange of information with Britain.

Stimson, Bush, and other officials met with Churchill and his advisors. Churchill made it clear that Britain's main interest was having nuclear weapons after the war, not commercial profit. Bush then suggested a plan, which Stimson agreed to present to Roosevelt.

A British official, John Anderson, wrote a draft agreement. Churchill made it sound more important. Anderson then took the draft to Washington. The final version included a key British request: the creation of the Combined Policy Committee. This committee would oversee the joint project with members from the United States, Britain, and Canada.

The Quebec Agreement is Signed

The agreement needed to be finalized quickly because Roosevelt, Churchill, and their advisors were meeting for the Quadrant Conference in Quebec City on August 17, 1943. The Canadian Prime Minister, Mackenzie King, hosted the meeting.

Even though Canada didn't sign the agreement, Britain felt Canada's help was important enough for them to have a representative on the Combined Policy Committee. King chose C. D. Howe, Canada's Minister of Munitions and Supply. The American members were Stimson, Bush, and Conant. The British members were Sir John Dill and J. J. Llewellin.

On August 19, Roosevelt and Churchill signed the Quebec Agreement. It was titled "Articles of Agreement governing collaboration between the authorities of the USA and UK in the matter of Tube Alloys." The main points were:

- The US and UK would combine their resources to develop nuclear weapons and share information freely.

- Neither country would use nuclear weapons against the other.

- Neither country would use nuclear weapons against other countries without both agreeing first.

- Neither country would share information about nuclear weapons with other countries without both agreeing first.

- Because the US was doing most of the work, the President could limit Britain's use of atomic energy for business after the war.

The part about needing mutual consent before using atomic bombs worried Stimson. If the US Congress had known, they might not have supported it. The agreement also showed that Britain was the junior partner in the alliance. Churchill believed it was the best deal he could get to ensure Britain had access to nuclear weapons technology after the war.

The Quebec Agreement was kept secret. Only a few people knew its terms. It wasn't even revealed to the US Congress until 1947. Churchill wanted to publish it in 1951, but President Harry S. Truman said no. It remained secret until Churchill read it out loud in the British Parliament in 1954. However, a Soviet spy had already reported details of the agreement in 1943.

Putting the Agreement into Action

Even before the agreement was signed, British scientists were told to go to North America. They arrived on the day the agreement was signed, but couldn't talk to American scientists right away. It took two weeks for American officials to learn the details of the agreement. The rules for British scientists working in the US were finally agreed upon in December 1943.

The Combined Policy Committee met only eight times over the next two years. The first meeting set up a Technical Subcommittee. James Chadwick became the head of the British Mission to the Manhattan Project and a member of this subcommittee.

There were still discussions about how the American and Canadian/British projects would work together. Chadwick pushed for resources to build a nuclear reactor in Canada. Britain and Canada would pay for it, but the US had to supply the heavy water needed. Groves agreed to supply the heavy water but with limits. The Canadian project could get information from American research reactors, but not from the main production reactors or details about plutonium chemistry.

Chadwick fully supported the British contribution to the Manhattan Project. He made sure that every request from Groves for help was met. British scientists helped with different parts of the project, including uranium separation and bomb design. For example, William Penney observed the bombing of Nagasaki and later participated in nuclear tests.

A problem arose in 1944 when the US found out that Britain had a secret agreement with a French scientist to share nuclear information with France after the war. The US and Canada said this broke the Quebec Agreement. Britain then had to break its promise to France to satisfy the US.

The issue of patent rights was also complicated. After the Quebec Agreement, British and American experts worked out a deal for patents related to nuclear technology. This agreement, which also included Canada, was finalized much later in 1956 due to the need for secrecy.

In July 1945, Henry Maitland Wilson, a British military leader on the Combined Policy Committee, agreed to the use of nuclear weapons against Japan. This was done under the clause of the Quebec Agreement that required mutual consent before using the bombs.

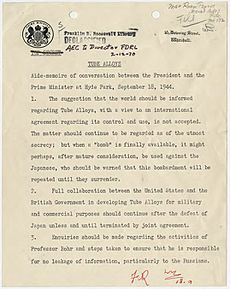

The Hyde Park Agreement

In September 1944, Roosevelt and Churchill met again in Quebec. After the conference, they spent time at Roosevelt's home in Hyde Park, New York. They talked about continuing their nuclear cooperation after the war. On September 19, they signed a document called the Hyde Park Aide-Mémoire. This document stated that full collaboration on nuclear technology for military and business purposes should continue after Japan's defeat, unless both countries agreed to end it.

Only a few of Roosevelt's advisors knew about this secret agreement. After Roosevelt died in April 1945, the American copy of the document couldn't be found. The British sent a copy to the US. Even then, General Groves doubted it was real until the American copy was found years later, misfiled in Roosevelt's papers.

The Agreement Ends

After the war, President Harry S. Truman (who took over after Roosevelt died) and Prime Minister Clement Attlee (who replaced Churchill) agreed to change the Quebec Agreement. They wanted a looser form of cooperation.

In November 1945, American and British officials met and agreed to keep the Combined Policy Committee. The requirement for "mutual consent" before using nuclear weapons was changed to "prior consultation." They also agreed to "full and effective cooperation" in basic scientific research. Truman and Attlee signed this new understanding.

However, cooperation quickly broke down. In April 1946, Truman stated that the US was not obligated to help Britain build its own atomic energy plants. Attlee was very unhappy about this. There was also a disagreement over sharing uranium ore, which was now needed by both countries. Eventually, Chadwick and Groves agreed to share the ore equally.

The discovery that a British physicist, Alan Nunn May, was a Soviet spy made it politically difficult for the US to share information with Britain. The US Congress, unaware of the Hyde Park agreement, passed the McMahon Act in 1946. This law stopped all technical cooperation and prevented allies from receiving any information. This angered British scientists and officials and led Britain to decide in January 1947 to develop its own nuclear weapons.

On January 7, 1948, the Quebec Agreement was officially ended and replaced by a new agreement called the modus vivendi. This allowed for limited sharing of technical information among the United States, Britain, and Canada. Like the Quebec Agreement, the modus vivendi was also kept secret.

As the Cold War began, the US became less interested in a close alliance with Britain. The reputation of the British was further damaged in 1950 when another spy, Klaus Fuchs, was revealed to be working for the Soviets. However, Britain's participation in the Manhattan Project gave them important knowledge. This knowledge was key to their own post-war nuclear weapons program. In 1958, the McMahon Act was changed, and the nuclear cooperation between America and Britain, known as the Special Relationship, restarted under the 1958 US–UK Mutual Defence Agreement.

Images for kids

-

Mackenzie King, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill at the Quebec Conference in August 1943

-

Sir John Anderson, the minister responsible for Tube Alloys

-

Vannevar Bush, Director of the US Office of Scientific Research and Development

-

Lord Cherwell (foreground, in bowler hat) was scientific advisor to Winston Churchill (centre)

-

Vannevar Bush, James B. Conant, Leslie Groves and Franklin Matthias

-

Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson (centre) with Field Marshals Sir Harold Alexander (left) and Sir Henry Maitland Wilson (right)

-

Press Conference at the Citadelle of Quebec during the Quadrant Conference. Left to right: President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Seated on the wall behind them are Anthony Eden, Brendan Bracken and Harry Hopkins.

-

The Hyde Park Aide-Mémoire. This copy is in the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

-

President Harry Truman and prime ministers Clement Attlee and Mackenzie King board the USS Sequoia for discussions about nuclear weapons, November 1945

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |