William Penney, Baron Penney facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

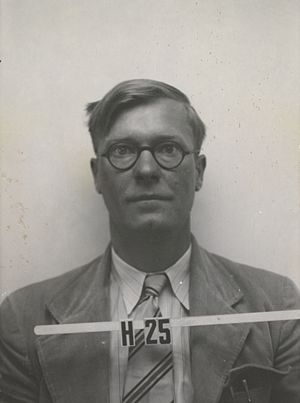

The Lord Penney

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

William George Penney

24 June 1909 |

| Died | 3 March 1991 (aged 81) East Hendred, Oxfordshire, England

|

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Institutions |

|

William George Penney, Baron Penney (born June 24, 1909 – died March 3, 1991) was a brilliant British mathematician and physicist. He became a professor at Imperial College London. Penney played a very important role in developing Britain's first atomic bomb. This secret project, called High Explosive Research, started in 1942 during World War II. Britain successfully tested its first atomic bomb in 1952.

During World War II, Penney worked with American scientists on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos Laboratory. He helped calculate how much damage an atomic bomb's blast wave would cause. When he returned to Britain, he led the country's nuclear weapons program, known as Tube Alloys. He also directed scientific research at the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment. This work led to the first British nuclear bomb test, called Operation Hurricane, in 1952.

After the test, Penney became a top advisor for the new United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA). He later became its chairman. He used his position to help with international talks about controlling nuclear tests. This led to the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. Penney also made important scientific contributions in mathematics, especially in understanding how waves move. He also worked on problems in hydrodynamics, which is about how liquids move. Later in his career, he taught mathematics and physics. He was the head (Rector) of Imperial College London from 1967 to 1973.

Contents

Early Life and Learning

William George Penney was born in Gibraltar on June 24, 1909. He was the oldest child and only son of William Alfred Penney, a soldier in the British Army. His mother, Blanche Evelyn Johnson, used to be a cashier. His parents moved often because of his father's army work.

During World War I, William, his mother, and sisters moved to Sheerness, Kent. He went to primary school there. He later attended Sheerness Technical School for Boys from 1924 to 1926. He showed a great talent for science. He was also good at sports like boxing, athletics, cricket, and soccer.

In 1927, Penney started working as a laboratory assistant. This job helped him get scholarships to the Royal College of Science (RCS), which is part of Imperial College London. He was so smart that he skipped his first year. He graduated in 1929 at age 20 with a Bachelor of Science degree in mathematics. He earned top honors.

Penney continued his studies at the University of London. He spent some time in the Netherlands, working with Ralph Kronig. Together, they created the Kronig–Penney model. This model helps explain how electrons move in certain materials. Penney earned his PhD in Mathematics in 1931. He then traveled to the United States for more research. He visited famous labs and even met Robert Oppenheimer.

In 1933, Penney returned to England and studied at Trinity College, Cambridge. He switched his focus from pure mathematics to physics. He researched how metals are structured and how crystals behave magnetically. In 1935, he earned another PhD from the University of Cambridge. In 1936, he became a lecturer in Mathematics at Imperial College London. He held this job until 1945. On July 27, 1935, Penney married Adele Minnie Elms. They had two sons, Martin and Christopher.

World War II Contributions

Explosion Physics

When World War II started in September 1939, Penney offered his scientific skills for the war effort. He was asked by G. I. Taylor, an expert in how fluids move, to study underwater explosions. Penney joined the Physics of Explosives Committee (Physex). He reported his findings to another group, Undex, which was interested in how underwater explosions from mines or torpedoes affected ships.

Penney also helped design and build Bombardon breakwaters with Royal Navy engineers. These were large steel structures used as part of the Mulberry harbours after the D-Day invasion in Normandy. These floating breakwaters protected landing ships and soldiers from ocean waves. Penney's job was to figure out how waves would affect them and how to arrange them best.

Manhattan Project Work

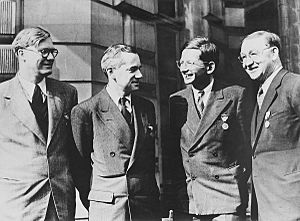

In August 1943, an agreement allowed British scientists to help with the American Manhattan Project. This project aimed to build atomic bombs. Penney was sent to the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico because of his knowledge of explosions. At Los Alamos, Penney was recognized for his scientific skills and his ability to work well with others. He quickly became part of the main group of scientists making important decisions for the project.

One of Penney's main tasks was to predict the damage caused by an atomic bomb's blast wave. He gave talks on this topic. Major General Leslie Groves, who led the Manhattan Project, said Penney was one of the key advisors for important decisions.

On April 27, 1945, Penney helped choose the cities that would be targets. He advised on the best height for the bomb to explode to cause the most damage without leaving lasting radiation on the ground. The committee chose four cities. Penney tried to guess how many people would be hurt and how much damage would occur. This was hard because they didn't know the exact power of the bombs yet. The Trinity test on July 16, 1945, helped answer this. Penney was supposed to watch the test from a plane, but bad weather stopped him. Five days later, he explained the test results. He predicted the bomb could destroy a city of three or four hundred thousand people.

The next month, Penney went to Tinian Island as part of Project Alberta. This group of scientists and military people assembled the atomic bombs. Penney represented the United Kingdom. He was not allowed to observe the bombing of Hiroshima. However, he was allowed to go on the second mission. On August 9, 1945, Penney witnessed the bombing of Nagasaki from an observation plane. After Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945, Penney was part of the team that went into Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Their job was to study the effects of the nuclear weapons.

Penney returned to the United Kingdom in September 1945. He brought back items from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He went back to Imperial College and wrote a report on the bombings. He estimated the Hiroshima bomb had a power of about 10,000 tons of TNT, and the Nagasaki bomb about 30,000 tons of TNT. He wanted to go back to teaching and research.

Britain's Nuclear Weapons Program

After the war, the British government believed that America would share its atomic technology. This was because they saw it as a joint discovery. In December 1945, the Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, ordered the building of an atomic pile to make plutonium. He also asked for a report on what Britain would need to build its own atomic bombs. Penney was asked to lead the Armament Research department at Fort Halstead. He suspected Britain would build its own bomb and wanted to be in charge. In this role, he was responsible for all types of weapons research.

In 1946, Penney went back to the United States. He led studies on the blast effects for Operation Crossroads at Bikini Atoll. He wrote reports on the effects of the two nuclear tests. His reputation grew when he could figure out the bomb's power using simple devices, even when the fancy test equipment failed. The second test, Baker, was underwater and greatly impressed Penney. He thought about what would happen if an atomic bomb exploded near a British port city.

In August 1946, the American McMahon Act was passed. This law meant Britain could no longer access US atomic research. Penney returned to the UK and planned for an atomic weapons section in his department. In January 1947, he went back to the US for a meeting on the Crossroads tests. Since most atomic cooperation had ended, his personal role was important for keeping contact between the two countries.

The British government decided Britain needed its own atomic bomb to remain a powerful country. The Foreign Secretary, Ernest Bevin, famously said, "We've got to have this thing over here, whatever it costs... We've got to have the bloody Union Jack flying on top of it." The decision to build the bomb was made in January 1947. Penney was put in charge of the project, code-named "High Explosive Research" (HER). In May 1947, Penney officially became the head of HER. He began gathering teams of scientists and engineers to develop the new technologies needed. He gave a two-hour talk to his team on how to build an atomic bomb.

By mid-1948, Penney realized he needed more staff than he first thought. He asked for a new, separate site for HER for safety and security reasons. This was approved, and a former airbase, RAF Aldermaston, was chosen. The site was taken over on April 1, 1950. Penney became the Chief Superintendent of High Explosive Research. The first part of the work at Aldermaston was finished in December 1951. On October 3, 1952, the first British nuclear device was successfully exploded. This test, called "Operation Hurricane", happened off the coast of Australia in the Monte Bello Islands.

Britain's Hydrogen Bomb

"Hurricane" was just the first of Britain's nuclear weapons tests in Australia. Future tests needed a land site. Penney visited Australia and chose a site at Emu Field in South Australia for the Operation Totem tests in 1953. Emu Field was too far away, so Penney picked a more accessible site at Maralinga.

Britain decided to develop a hydrogen bomb, which is much more powerful than an atomic bomb. They needed scientific information quickly, and Maralinga wasn't ready. So, a second series of tests, Operation Mosaic, happened in the Monte Bello Islands in 1956. The Operation Buffalo tests were then carried out at Maralinga in September and October 1956. Penney personally oversaw the Totem and Buffalo tests.

Penney understood that the public cared about these tests. He gave clear talks to the Australian press. Before one series of tests, a British official said Penney's honest and sincere manner made him very popular in Australia.

Britain felt it needed to quickly develop very powerful (megaton-class) weapons. This was because it seemed that testing nuclear bombs in the atmosphere might soon be banned by a treaty. The Prime Minister, Harold Macmillan, hoped to convince the US to change a law (the McMahon Act) that stopped them from sharing nuclear information with Britain. He wanted to show that the UK could make a hydrogen bomb. Penney was put in charge of this. The Orange Herald bomb was developed. It was presented as a thermonuclear bomb, but most of its energy came from a different process. However, Britain's later success in developing true thermonuclear weapons, along with the Sputnik crisis, led to the McMahon Act being changed. This brought back the nuclear Special Relationship with the United States.

In the late 1950s, there was pressure to stop testing nuclear weapons in the atmosphere. Penney led the UK team at a conference in Geneva in July 1958. He also advised Prime Minister Macmillan at a conference in Bermuda in 1961, which led to the Nassau Agreement. Penney continued to advise the government on arms control. He was involved in the talks that led to the signing of the Partial Test Ban Treaty in Moscow in July 1963.

Nuclear development was moved to the new United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA). Penney joined the UKAEA Board in 1954. He also led the official investigation into the Windscale fire in 1957. He became the Member for Scientific Research in 1959, deputy chairman in 1961, and chairman in 1964. Penney preferred to avoid arguments and find common ground. He supported the decision in 1966 to develop the Advanced Gas-cooled Reactor. He also decided to build the Prototype Fast Reactor at Dounreay.

Imperial College Leadership

Penney was the head (Rector) of Imperial College London from 1967 to 1973. This job was much harder than he expected. He had no time for his own research. Universities had grown quickly in the 1960s, and there were many problems with staff and money. He had to deal with protests from staff and students. Penney agreed to let students observe Board meetings. He also worked out agreements with the Association of University Teachers. Imperial College now got money directly from the government, but money was still tight. Careful money management helped the college have more income than expenses. The college named the William Penney Laboratory in his honor in 1988. He also served as the first chairman of the UK's Standing Committee on Structural Safety from 1976 to 1982.

Awards and Recognition

Penney became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1946. He was also its treasurer and vice-president for several years. He became a member of the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1962. He also joined the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1970 and the American Philosophical Society in 1973. He received many awards, including the Wilhelm Exner Medal in 1967. In 1969, he received the Rumford Medal, the Glazebrook Medal and Prize, and the James Alfred Ewing Medal. The next year, he was awarded the Kelvin Gold Medal. He also received honorary degrees from several universities. For his help to the United States, he was given the Medal of Freedom in 1946.

Penney was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1946. He was then made a Knight Commander of the order in 1952. In 1967, he became a life peer, which meant he could sit in the House of Lords. He took the title Baron Penney. In 1969, he was awarded the Order of Merit. He attended the House of Lords only a few times and voted on a few important bills.

Later Life and Legacy

In his later years, Penney admitted he had some doubts about his work, but he felt it was necessary. In 1985, he was questioned about the nuclear tests in Australia. He said that at least one of the twelve tests had unsafe levels of fallout. However, he insisted that great care was taken and that the tests followed the safety rules of that time. The official inquiry mostly agreed with Penney. But some stories in the press suggested otherwise. Penney's health was affected by this experience. He was diagnosed with cancer in 1991 and died on March 3, 1991, at age 81. He burned his personal papers before he died.

In his obituary, the New York Times called him the "father of the British bomb." The Guardian said he was its "guiding light." His scientific and leadership skills were very important for creating the bomb successfully and on time. His leadership in exploding the first British hydrogen bomb helped restore the sharing of nuclear technology between Britain and the US in 1958. He also played a key role in the talks that led to the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963. His Kronig-Penney model is still taught and used today in physics. It helps explain how electrons behave in materials.

See also

In Spanish: William Penney para niños

In Spanish: William Penney para niños

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |