Harold Macmillan facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Earl of Stockton

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

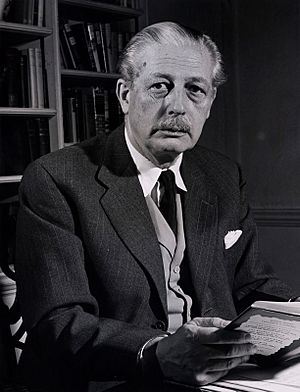

Official portrait, 1959

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 January 1957 – 18 October 1963 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Elizabeth II | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Rab Butler (1962–1963) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Anthony Eden | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Alec Douglas-Home | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader of the Conservative Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 10 January 1957 – 18 October 1963 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman | The Lord Poole The Viscount Hailsham Rab Butler Iain Macleod |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Anthony Eden | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Alec Douglas-Home | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

Maurice Harold Macmillan

10 February 1894 London, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 29 December 1986 (aged 92) Chelwood Gate, East Sussex, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | St Giles' Church, Horsted Keynes, West Sussex, England | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Conservative | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Lady Dorothy Cavendish

(m. 1920; died 1966) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 4, including Maurice and Caroline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Civilian awards |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | British Army | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1914–1920 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Captain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unit | Grenadier Guards | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military awards | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, often known as Harold Macmillan, was a British politician. He was the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. People sometimes called him "Supermac" because of his calm and clever way of handling things.

Macmillan was hurt while serving as a soldier in the First World War. This caused him pain and made it hard for him to move for the rest of his life. After the war, he worked in his family's book-publishing business. He then became a Member of Parliament (MP) in 1924. He lost his seat in 1929 but won it back in 1931. He spoke out about the high number of people without jobs in his area. He also disagreed with the government's policy of trying to avoid war with Germany by giving in to its demands.

During the Second World War, Macmillan became an important government official. He worked closely with Prime Minister Winston Churchill. In the 1950s, he served as the Foreign Secretary (in charge of relations with other countries) and Chancellor of the Exchequer (in charge of the country's money). He held these jobs under Prime Minister Anthony Eden.

When Anthony Eden resigned in 1957, Macmillan became Prime Minister and the leader of the Conservative Party. He believed in helping all parts of society and supported a mixed economy. This meant some industries were owned by the government, and trade unions were strong. He focused on spending money to keep people employed and to help the economy grow. During his time as Prime Minister, Britain saw a period of wealth, with low unemployment. In 1957, he famously said that the nation had "never had it so good." He led his party to a big win in the 1959 election.

In foreign affairs, Macmillan worked to fix Britain's relationship with the United States after the Suez Crisis in 1956. He also helped many African countries gain their independence from Britain. He changed Britain's defense plans for the nuclear age. He ended National Service (where young men had to join the military). He also worked with the US and the Soviet Union to create the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, which stopped nuclear weapons tests in the atmosphere. Towards the end of his time as Prime Minister, his government faced some scandals. After he resigned, Macmillan lived a long life as an older, respected politician. He passed away in 1986 at the age of 92.

Macmillan was the last British Prime Minister born during the Victorian era. He was also the last to have fought in the First World War and the last to receive a special title that passes down in his family.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Family Background

Harold Macmillan was born on 10 February 1894, in London. His father, Maurice Crawford Macmillan, was a publisher. His mother, Helen Artie Tarleton Belles, was an artist from the United States. Harold had two older brothers, Daniel and Arthur. His grandfather, Daniel MacMillan, started the Macmillan Publishers company. He was from the Isle of Arran in Scotland. Harold Macmillan always felt a strong connection to Scotland.

Schooling and University

Macmillan had a very good education from a young age. He learned French from his nannies and studied Latin and Greek. He went to Summer Fields School and then to Eton College. At Eton, he was often sick, and he missed his last year there. He was taught at home by private teachers.

In 1912, Macmillan went to Balliol College, Oxford. He joined many political groups there. He was interested in different political ideas, including those of the Conservative and Liberal parties. He was very active in the Oxford Union Society, which is a debating club. He would likely have become its president if the war had not started. He did very well in his first university exams in 1914.

Military Service in World War I

When the First World War began, Macmillan joined the army right away. He became an officer in the King's Royal Rifle Corps and then the Grenadier Guards. He fought on the front lines in France, where many soldiers were killed or injured. He was wounded three times. In September 1915, during the Battle of Loos, he was shot in the hand and grazed on the head. He returned to France in 1916.

During the Battle of the Somme in September 1916, he was badly wounded. He lay in a shell hole for over twelve hours, sometimes pretending to be dead when German soldiers passed by. He spent the last two years of the war in the hospital, having many operations. His hip wound took four years to heal completely, and he walked with a slight limp for the rest of his life.

After the war, Macmillan did not go back to Oxford to finish his degree. He felt the university would not be the same because so many of his friends had died in the war.

Post-War Life

In 1919, Macmillan worked in Canada as an assistant to the Governor General of Canada, Victor Cavendish, 9th Duke of Devonshire. He later married the Duke's daughter, Lady Dorothy.

After returning to London in 1920, he joined his family's publishing company, Macmillan Publishers. In 1936, he and his brother Daniel took charge of the company. Harold focused on political and non-fiction books. He left the company when he became a government minister in 1940. He returned to work there from 1945 to 1951 when his party was not in power.

Personal Life

Marriage and Children

Harold Macmillan married Lady Dorothy Cavendish on 21 April 1920. She was the daughter of the 9th Duke of Devonshire. They were married for 46 years until Lady Dorothy passed away in 1966.

The Macmillans had four children:

- Maurice Macmillan, Viscount Macmillan of Ovenden (1921–1984)

- Lady Caroline Faber (1923–2016)

- Lady Catherine Amery (1926–1991)

- Sarah Heath (1930–1970)

Early Political Career (1924–1951)

Member of Parliament (1924–1929)

Macmillan first ran for Parliament in 1923 in the area of Stockton-on-Tees. He won in 1924. He lost his seat in 1929 because of high unemployment in his area. He returned to the House of Commons for Stockton-on-Tees in 1931.

Member of Parliament (1931–1939)

During the 1930s, Macmillan was a backbench MP, meaning he was not a government minister. He wrote books and articles about economic ideas, suggesting that the government should play a bigger role in managing the economy. He disagreed with the government's policy of trying to avoid war by giving in to Germany's demands.

World War II Service (1939–1945)

Macmillan became a government official during the Second World War. From 1940, he worked in the Ministry of Supply, helping to provide weapons and equipment for the British Army and Royal Air Force. He traveled around the country to help with production.

In 1942, he became the Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies. This was a junior role, but he was part of the Privy Council, a group of important advisors to the Queen.

Later in 1942, Macmillan was given a very important job as the British Minister Resident in Algiers, North Africa. This area had recently been freed from enemy control. He reported directly to Prime Minister Churchill. He worked closely with the American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, who was the Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean. Macmillan believed that Britain, like ancient Greece, could guide the powerful United States, like ancient Rome.

In February 1943, Macmillan was badly burned in a plane crash. He was still recovering for a long time. He helped negotiate the Italian armistice in 1943, which was a ceasefire agreement. He also played a role in events in Greece in 1944, helping to ensure a pro-British government remained in power.

Air Secretary (1945)

After the war in Europe ended, Macmillan returned to England. He felt like a "stranger at home." He served as Secretary of State for Air for two months in Churchill's temporary government.

In Opposition (1945–1951)

Macmillan lost his seat in the 1945 election, which was a big win for the Labour Party. However, he returned to Parliament in November 1945, winning a by-election in Bromley. He became a strong voice for the Conservative Party while they were not in power. He also worked to support greater European cooperation to prevent future wars.

Government Minister (1951–1957)

Housing Minister (1951–1954)

When the Conservatives won the election in 1951, Macmillan became the Minister of Housing and Local Government. Prime Minister Churchill gave him the important task of building 300,000 new houses each year. Macmillan thought this would be a very difficult job, but he achieved his goal by the end of 1953, a year ahead of schedule. This made him very popular.

Defence Minister (1954–1955)

From October 1954, Macmillan was the Minister of Defence. During this time, Britain started to rely more on nuclear weapons for its defense. In 1955, the government announced its decision to produce the hydrogen bomb.

Foreign Secretary (1955)

In April 1955, Macmillan became the Foreign Secretary under Prime Minister Anthony Eden. After attending a meeting in Geneva, he famously said, "There ain't gonna be no war," meaning he believed peace was possible.

Chancellor of the Exchequer (1955–1957)

Macmillan became Chancellor of the Exchequer in December 1955. He was in charge of the country's money. One of his new ideas was to introduce premium bonds in 1956. These were special bonds that gave people a chance to win tax-free prizes instead of earning interest. They became very popular.

The Suez Crisis

In November 1956, Britain, along with France and Israel, invaded Egypt during the Suez Crisis. This happened after Egypt's leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser, took control of the Suez Canal. Macmillan was very supportive of the invasion at first. He believed that if Nasser succeeded, Britain's influence in the Arab world would end. He was involved in the secret planning of the invasion.

However, the United States strongly opposed the invasion. The US government put financial pressure on Britain, causing the British currency to lose value very quickly. Macmillan realized the financial danger and pushed for Britain to withdraw its forces. He told the Cabinet that Britain was losing a lot of money every day. Because of this, Britain had to agree to withdraw. The Suez Canal remained under Egyptian control.

Macmillan later said he regretted the damage done to Britain's relationship with the US.

Becoming Prime Minister

After the Suez Crisis, Prime Minister Anthony Eden resigned in January 1957 due to ill health. The Conservative Party did not have a formal way to choose a new leader at that time. Queen Elizabeth II appointed Macmillan as Prime Minister after getting advice from important politicians like Winston Churchill. Many people had expected Rab Butler, Eden's deputy, to be chosen. When Macmillan took office, he told the Queen he wasn't sure his government would last "six weeks." However, he ended up leading the country for more than six years.

Prime Minister (1957–1963)

First Government (1957–1959)

When he became Prime Minister, Macmillan wanted to show a calm and stylish image, different from his predecessor. He was known for his love of reading classic books. He also appointed many people from his old school, Eton, to government jobs. He was nicknamed "Supermac" by a cartoonist, which was meant to be a joke but became a popular and friendly name for him.

Economy and Domestic Policies

Macmillan's main focus was the economy. He wanted to keep unemployment low, especially with an election coming up. This was different from some of his financial ministers who wanted to cut spending. In January 1958, three of his Treasury ministers, including the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Peter Thorneycroft, resigned because they disagreed with his spending plans. Macmillan famously called this "a little local difficulty."

During his time as Prime Minister, the average living standards in Britain improved. Many social changes were made, including new laws about housing, offices, and noise. A new pension scheme was introduced to help retired people. The standard work week was also reduced from 48 to 42 hours.

Foreign Policy and Decolonization

Macmillan took a strong role in foreign policy. He worked to improve relations with the United States, helped by his wartime friendship with President Eisenhower.

In February 1959, Macmillan visited the Soviet Union. His talks with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev helped reduce tensions between East and West.

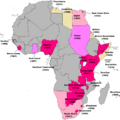

Macmillan was a big supporter of decolonization, which meant giving independence to countries that were part of the British Empire. The Gold Coast became independent as Ghana in 1957, and Malaya also gained independence that year.

Nuclear Weapons

Macmillan strongly supported Britain's nuclear weapons program. He believed that having its own hydrogen bomb would help Britain work more closely with the United States on nuclear technology. Britain successfully tested its hydrogen bomb in November 1957.

Macmillan also agreed to let the US base Thor missiles in England. This helped lead to an agreement in 1958 that allowed the US and Britain to share nuclear technology. He saw the launch of the Soviet satellite Sputnik as a chance to increase Britain's influence with the US. He pushed President Eisenhower to allow more nuclear cooperation.

Macmillan believed that the US was too strict with the Soviet Union. He wanted to improve relations and reduce Cold War tensions.

1959 General Election

Macmillan led the Conservative Party to a big victory in the 1959 United Kingdom general election. His party increased its majority in Parliament. The campaign focused on how the economy had improved and how people's lives were getting better. His famous phrase, "You've never had it so good," became a symbol of the time. This victory was partly due to workers having more money and being able to buy more consumer goods.

Second Government (1959–1963)

Economy and Changes

Britain faced problems with its balance of payments (the difference between money coming into and leaving the country). This led the Chancellor, Selwyn Lloyd, to freeze wages for seven months in 1961. This made the government less popular. In July 1962, Macmillan made big changes to his Cabinet, firing eight ministers. This was known as the "Night of the Long Knives" and was seen by many as a sign of panic.

Macmillan supported the creation of the National Economic Development Council (NEDC) in 1961, which aimed to help the economy grow. However, other efforts to control wages were less successful. In 1963, a report called for major cuts to Britain's railway network, known as the "Beeching Axe." This closed many railway lines and stations.

Foreign Policy and US Relations

Macmillan traveled more than any previous Prime Minister. He played an important role in trying to set up a summit in Paris in 1960 to discuss the Berlin crisis. However, the meeting failed because of a US spy plane incident. This made Macmillan think that Britain needed to have a stronger role in Europe.

His close relationship with the United States continued after John F. Kennedy became President. Macmillan offered Kennedy advice and support, especially after Kennedy faced challenges like the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. Macmillan was very supportive during this crisis, and Kennedy consulted him daily.

Macmillan also played a key role in the negotiations for the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963. This treaty banned all nuclear weapons tests above ground. Macmillan wanted this treaty to reduce public fear about nuclear weapons and to maintain Britain's role as a major world power.

Wind of Change Speech

Macmillan's second government saw a faster pace of decolonization in Africa. He believed that if keeping a colony cost more than it benefited Britain, it should be given independence. After facing criticism about colonial policies in Kenya and Nyasaland, Macmillan decided that African colonies were becoming a problem. He argued that holding onto them would lead to more criticism, costly wars, and allow the Soviet Union to gain influence.

He appointed Iain Macleod as Colonial Secretary, who greatly sped up the process of giving independence. In 1960, Macmillan went on his "Wind of Change" tour of Africa. He gave his famous 'wind of change' speech in Cape Town on 3 February 1960. In this speech, he spoke about the growing desire for independence across Africa.

Many countries gained independence during his time as Prime Minister: Nigeria, Southern Cameroons, and British Somaliland in 1960; Sierra Leone and Tanganyika in 1961; Trinidad and Tobago and Uganda in 1962; and Kenya in 1963. Most of these countries remained part of the Commonwealth of Nations.

In Southeast Asia, Malaya, Sabah, Sarawak, and Singapore became independent as Malaysia in 1963. Macmillan wanted to ensure that the new state of Malaysia had a Malay majority to keep it stable and pro-Western. He also wanted Britain to keep military bases in Malaysia, especially in Singapore, to maintain British power in Asia.

The Indonesian president Sukarno opposed the creation of Malaysia. This led to a conflict called the Indonesian Confrontation, an undeclared war between Britain and Indonesia from 1963 to 1966. Macmillan saw Sukarno as a difficult leader and felt that giving in to his demands would harm British prestige.

Skybolt Crisis and Europe

Macmillan decided to cancel the British Blue Streak missile project in 1960. Instead, he chose for Britain to join the American Skybolt missile project. He also allowed the US Navy to base Polaris submarines in Scotland. When the US suddenly cancelled the Skybolt project, Macmillan negotiated with President Kennedy to buy Polaris missiles instead. This agreement was made in December 1962.

Macmillan also worked to form the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) with other European countries. However, as the European Communities (EEC) became more successful, Britain decided to apply to join it. Macmillan formally applied in July 1961, despite concerns from some members of his party and the press. However, France's president, Charles de Gaulle, vetoed Britain's entry in January 1963. De Gaulle believed Britain was too closely linked to the US and that its entry would reduce France's role in Europe.

End of Premiership

By the early 1960s, some people felt that Macmillan's old-fashioned manners were out of date. Satirical shows often made fun of him. The Vassall affair in 1962, where a government clerk was caught spying for the Soviet Union, also damaged his reputation.

Resignation

In the summer of 1963, some Conservative Party leaders urged Macmillan to retire. He was considering his options when he became ill on the eve of the Conservative Party conference in October 1963. He had an operation and, while recovering in the hospital, decided to resign.

Succession

Macmillan resigned on 18 October 1963, after almost seven years as Prime Minister. He was succeeded by the Foreign Secretary, Alec Douglas-Home. There was some debate about how his successor was chosen, with some suggesting that Macmillan had influenced the decision to ensure that Rab Butler was not chosen again.

Retirement (1963–1986)

Oxford Chancellor (1960–1986)

Macmillan was elected Chancellor of the University of Oxford in 1960. He held this position for the rest of his life. He often attended university events, gave speeches, and helped raise money. He was known for having interesting conversations with students.

Return to Publishing

After retiring from politics, Macmillan became the chairman of his family's publishing company, Macmillan Publishers, from 1964 to 1974. He also wrote a six-volume autobiography about his life.

Later Political Views

Macmillan continued to comment on politics after he retired. He accepted the Order of Merit in 1976, a special honor. In 1976, he suggested that Britain needed a "Government of National Unity" with all parties working together to solve economic problems.

He became more involved in politics after Margaret Thatcher became the Conservative leader in 1975 and Prime Minister in 1979. He offered her advice, including during the Falklands War in 1982.

In 1984, he was given a special title and became the Earl of Stockton. He was the last Prime Minister to receive such a title that passes down through his family. In the House of Lords, he criticized Thatcher's handling of the coal miners' strike. He also famously compared Thatcher's policy of selling off state-owned companies to "selling the family silver," meaning selling valuable assets to solve financial problems.

Death and Legacy

Harold Macmillan passed away at his family home in East Sussex on 29 December 1986. He was 92 years old. He was the oldest British Prime Minister until Lord Callaghan surpassed his age in 2005.

Many people, including Margaret Thatcher and US President Ronald Reagan, paid tribute to him. He was buried next to his wife, parents, and son at St Giles' Church, Horsted Keynes.

Historians have different views on Macmillan's time as Prime Minister. Some remember him for the "affluent society" and rising living standards. Others point to economic challenges and the scandals that happened towards the end of his time in office. He is remembered as a complex and clever leader who played a key role in Britain's history during a time of great change.

Cabinets (1957–1963)

January 1957 – October 1959

- Harold Macmillan: Prime Minister

- Lord Kilmuir: Lord Chancellor

- Lord Salisbury: Lord President of the Council

- Rab Butler: Lord Privy Seal and Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Peter Thorneycroft: Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Selwyn Lloyd: Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Alan Lennox-Boyd: Secretary of State for the Colonies

- Lord Home: Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations

- Sir David Eccles: President of the Board of Trade

- Charles Hill: Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Lord Hailsham: Minister of Education

- John Scott Maclay: Secretary of State for Scotland

- Derick Heathcoat Amory: Minister of Agriculture

- Iain Macleod: Minister of Labour and National Service

- Harold Arthur Watkinson: Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation

- Duncan Edwin Sandys: Minister of Defence

- Lord Mills: Minister of Power

- Henry Brooke: Minister of Housing and Local Government and Welsh Affairs

Change

- March 1957 – Lord Home succeeds Lord Salisbury as Lord President, remaining Commonwealth Relations Secretary.

- September 1957 – Lord Hailsham succeeds Lord Home as Lord President, Home remaining Commonwealth Relations Secretary. Geoffrey Lloyd succeeds Hailsham as Minister of Education. The Chief Secretary to the Treasury, Reginald Maudling, enters the Cabinet.

- January 1958 – Derick Heathcoat Amory succeeds Peter Thorneycroft as Chancellor of the Exchequer. John Hare succeeds Amory as Minister of Agriculture.

October 1959 – July 1960

- Harold Macmillan: Prime Minister

- Lord Kilmuir: Lord Chancellor

- Lord Home: Lord President of the Council and Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations

- Lord Hailsham: Lord Privy Seal and Minister of Science

- Derick Heathcoat Amory: Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Rab Butler: Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Selwyn Lloyd: Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Iain Macleod: Secretary of State for the Colonies

- Reginald Maudling: President of the Board of Trade

- Charles Hill: Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Sir David Eccles: Minister of Education

- Lord Mills: Chief Secretary to the Treasury

- Ernest Marples: Minister of Transport

- Duncan Edwin Sandys: Minister of Aviation

- Harold Arthur Watkinson: Minister of Defence

- John Scott Maclay: Secretary of State for Scotland

- Edward Heath: Minister of Labour and National Service

- John Hare: Minister of Agriculture

- Henry Brooke: Minister of Housing and Local Government and Welsh Affairs

July 1960 – October 1961

- Harold Macmillan: Prime Minister

- Lord Kilmuir: Lord Chancellor

- Lord Hailsham: Lord President of the Council and Minister of Science

- Edward Heath: Lord Privy Seal

- Selwyn Lloyd: Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Rab Butler: Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Lord Home: Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Iain Macleod: Secretary of State for the Colonies

- Duncan Edwin Sandys: Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations

- Reginald Maudling: President of the Board of Trade

- Charles Hill: Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Sir David Eccles: Minister of Education

- Lord Hailsham: Minister of Science

- Lord Mills: Chief Secretary to the Treasury

- Ernest Marples: Minister of Transport

- Peter Thorneycroft: Minister of Aviation

- Harold Arthur Watkinson: Minister of Defence

- John Scott Maclay: Secretary of State for Scotland

- John Hare: Minister of Labour and National Service

- Christopher Soames: Minister of Agriculture

- Henry Brooke: Minister of Housing and Local Government and Welsh Affairs

October 1961 – July 1962

- Harold Macmillan: Prime Minister

- Lord Kilmuir: Lord Chancellor

- Lord Hailsham: Lord President of the Council and Minister of Science

- Edward Heath: Lord Privy Seal

- Selwyn Lloyd: Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Rab Butler: Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Lord Home: Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Reginald Maudling: Secretary of State for the Colonies

- Duncan Edwin Sandys: Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations

- Frederick Erroll: President of the Board of Trade

- Iain Macleod: Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Sir David Eccles: Minister of Education

- Henry Brooke: Chief Secretary to the Treasury

- Ernest Marples: Minister of Transport

- Peter Thorneycroft: Minister of Aviation

- Harold Arthur Watkinson: Minister of Defence

- John Scott Maclay: Secretary of State for Scotland

- John Hare: Minister of Labour and National Service

- Christopher Soames: Minister of Agriculture

- Charles Hill: Minister of Housing and Local Government and Welsh Affairs

- Lord Mills: Minister without Portfolio

July 1962 – October 1963

- Harold Macmillan: Prime Minister

- Rab Butler: Deputy Prime Minister and First Secretary of State

- Lord Dilhorne: Lord Chancellor

- Lord Hailsham: Lord President of the Council and Minister of Science

- Edward Heath: Lord Privy Seal

- Reginald Maudling: Chancellor of the Exchequer

- Henry Brooke: Secretary of State for the Home Department

- Lord Home: Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- Duncan Edwin Sandys: Secretary of State for the Colonies and Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations

- Frederick Erroll: President of the Board of Trade

- Iain Macleod: Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster

- Sir Edward Boyle: Minister of Education

- John Boyd-Carpenter: Chief Secretary to the Treasury

- Ernest Marples: Minister of Transport

- Julian Amery: Minister of Aviation

- Peter Thorneycroft: Minister of Defence

- Michael Noble: Secretary of State for Scotland

- John Hare: Minister of Labour and National Service

- Christopher Soames: Minister of Agriculture

- Sir Keith Joseph: Minister of Housing and Local Government and Welsh Affairs

- Enoch Powell: Minister of Health

- William Deedes: Minister without Portfolio

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Harold Macmillan para niños

In Spanish: Harold Macmillan para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |