UK miners' strike (1984–85) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids United Kingdom miners' strike |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Support the Miners March, London, 1984

|

||||

| Date | 6 March 1984 – 3 March 1985 (11 months, 3 weeks and 4 days) | |||

| Location | ||||

| Goals |

|

|||

| Resulted in | Pit closures, job losses, foreign coal imports, political unrest. | |||

| Parties to the civil conflict | ||||

|

||||

| Lead figures | ||||

|

||||

| Number | ||||

|

||||

| Casualties | ||||

| Death(s) | 6 | |||

| Injuries |

|

|||

| Arrested | 11,291 | |||

| Detained | 150–200 | |||

| Charged | 8,392 | |||

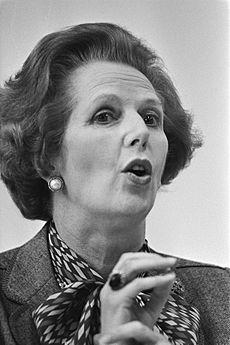

The miners' strike of 1984–1985 was a big protest by coal miners in Britain. They went on strike to try and stop coal mines from closing down. It was led by Arthur Scargill from the NUM. They were protesting against the National Coal Board (NCB), which was run by the government. The Conservative government, led by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, wanted to reduce the power of trade unions.

The NUM union was not fully united about the strike. Many miners, especially in the Midlands, kept working. Few other big unions supported the NUM because there wasn't a national vote by all miners. The year-long strike saw many angry clashes between striking miners and police. It ended with a clear win for the government. This allowed most of Britain's coal mines to close. Many people call it "the most bitter industrial dispute in British history." Over 26 million days of work were lost. This made it the largest strike since the 1926 general strike.

The strike started on March 6, 1984, at Cortonwood Colliery. The NUM's leader, Arthur Scargill, made the strike official across Britain on March 12, 1984. But he did not hold a national vote first, which caused a lot of arguments. The NUM hoped to cause a big energy shortage, like in the 1972 strike, to win. The government, led by Margaret Thatcher, had a plan. They built up large coal stocks. They also tried to keep as many miners working as possible. And they used police to stop pickets from attacking working miners. The NUM's failure to hold a national vote was a key factor in the strike's outcome.

The strike was declared illegal in September 1984 because there was no national vote. It ended on March 3, 1985. This strike was a major turning point for unions in Britain. The NUM's defeat greatly weakened the trade union movement. It was a big victory for Thatcher and the Conservative Party. The government was able to continue its economic plans. The number of strikes dropped sharply after 1985. Three people died because of events related to the strike.

The coal industry, much smaller now, was sold to private companies in December 1994. By the end of 2015, all 175 working pits from 1983 had closed. Poverty grew in former coal mining areas. In 1994, Grimethorpe in South Yorkshire was the poorest place in the country.

Contents

Understanding the Strike's Causes

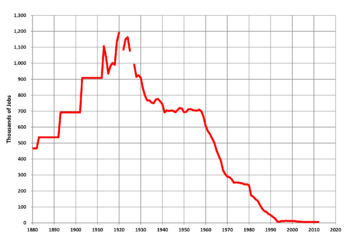

In the early 1900s, over 1,000 coal mines operated in the UK. By 1984, only 173 were still open. The number of miners had dropped from 1 million in 1922 to 231,000 by 1982. This decline in coal jobs was happening in many developed countries. For example, in the United States, coal mining jobs fell from 180,000 in 1985 to 70,000 in 2000.

The coal industry was owned by the government since 1947. It was managed by the National Coal Board (NCB). Like in most of Europe, the industry received a lot of government money. By 1984, the easiest coal to reach had been mined. The remaining coal was much more expensive to get. This meant the industry needed to use more machines and fewer workers. This made many miners lose their jobs.

After 1979, the government under Thatcher wanted to close mines faster. This was strongly opposed by the unions. In the past, mines only closed if workers agreed. Workers also received money and help to find new jobs. But this changed when closures were forced. Miners had very few other job options.

The Ridley Plan and Union Power

The miners' strike in 1974 helped bring down the government of Edward Heath. In response, the Conservative Party created the Ridley Plan. This was a secret report that explained how a future Conservative government could defeat a big strike. The plan suggested that trade unions had too much power. This power was hurting the economy. The government believed union power needed to be reduced.

The National Union of Mineworkers (NUM)

The mining industry was mostly a "closed shop." This meant that almost all workers had to be part of the union. If non-union workers were hired, it would cause a mass walkout. The NUM started in 1945. In 1947, most British coal mines became government-owned.

After World War II, there was high demand for coal. But over time, coal's share in the energy market decreased. Oil and nuclear power became more common. Many mines closed in the 1960s. This caused miners to move from older coalfields to Yorkshire and the Midlands. After some unofficial strikes, more radical leaders were elected to the NUM. They changed the rules to make it easier to call a strike.

The NUM had a regional structure. Some regions, like Scotland, South Wales, and Kent, were more radical. The Midlands were less so. In radical mining areas, miners who crossed picket lines were strongly disliked. In 1984, some mining villages had no other jobs nearby. In South Wales, miners showed strong unity. They came from isolated villages where most people worked in the mines.

From 1981, Arthur Scargill led the NUM. He was a strong union leader and a socialist. Scargill was a vocal opponent of Thatcher's government. He believed the government wanted to destroy the coal industry and the NUM. He also said that no mines should close unless they ran out of coal or became unsafe.

NACODS: Another Important Union

No mining could legally happen without an overman or deputy watching over it. Their union was the National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies and Shotfirers (NACODS). This union was less willing to strike. Their rules required two-thirds of members to vote for a national strike. During the 1972 strike, NACODS members could stay home with pay if picketing was too aggressive. This allowed them to show support without officially striking. Later in the 1984 strike, 82% of NACODS members did vote to strike.

Key Events of the Strike

Early Calls for Action

In January 1981, miners in Yorkshire voted to strike if any mine was threatened with closure. This led to a local strike. In February 1981, the government planned to close 23 mines. But the threat of a national strike made them back down. Thatcher realized she needed at least a six-month supply of coal to win a strike. In 1982, NUM members accepted a pay rise, rejecting a strike.

Between 1981 and 1984, the NCB cut 41,000 jobs. Many miners were transferred to other pits or to the new Selby Coalfield. The NUM held three national votes for strikes in 1982 and 1983. Each time, a minority voted in favor, not enough for a strike. In November 1983, the NUM started an overtime ban. This was still in place when the main strike began.

Thatcher's Strategy to Win

Thatcher expected Scargill to start a big conflict. She prepared a strong defense. She believed that expensive, inefficient mines had to close for the economy to grow. Her plan was to close these mines and rely more on imported coal, oil, gas, and nuclear power. She put tough leaders in key positions. She also stockpiled enough coal for at least six months.

Thatcher's team also set up mobile police units. These units could move quickly to stop pickets from blocking coal transport. Scargill helped her plan by calling the strike at the end of winter. This was when the demand for coal was going down.

In 1983, Thatcher appointed Ian MacGregor to lead the National Coal Board. He had a reputation for cutting jobs to make companies more efficient. This made it seem likely that coal jobs would be cut too. Clashes between MacGregor and Scargill seemed unavoidable.

The Debate Over a National Vote

On April 19, 1984, NUM leaders voted 69–54 against holding a national vote for the strike. Arthur Scargill argued against it. He believed that local areas should decide. He said that areas would strike one by one, like a "domino effect."

Without a national vote, most miners in Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire, South Derbyshire, North Wales, and the West Midlands kept working. A large number in Lancashire also worked. The police protected these working miners from aggressive picketing.

Mine Closures Announced

On March 6, 1984, the NCB announced plans to close 20 mines. This would mean 20,000 job losses. Many communities in Northern England, Scotland, and Wales would lose their main source of jobs. Scargill said the government planned to close over 70 mines. The government denied this. But later papers showed MacGregor did want to close 75 pits.

The Thatcher government had prepared for a strike. They stockpiled coal and converted some power stations to burn oil. They also hired truck drivers to transport coal. This was in case railway workers went on strike to support the miners.

The Strike Begins

Miners in different coalfields started striking. In Yorkshire, miners at several pits were already on unofficial strike. On March 5, the NCB announced that five pits would close very quickly. These included Cortonwood, which had been considered safe. The next day, pickets from Yorkshire appeared at mines in Nottinghamshire. On March 12, Scargill declared the NUM's support for the regional strikes. He called for action from all NUM members. But he chose not to hold a national vote.

Picket Line Clashes

The strike was widely supported in South Wales, Yorkshire, Scotland, North East England, and Kent. But there was less support in the Midlands and North Wales. Nottinghamshire became a target for aggressive picketing. Scargill's pickets tried to stop local miners from working.

The 'Battle of Orgreave' happened on June 18, 1984. Striking miners tried to block the Orgreave Coking Plant. About 5,000 miners and 5,000 police clashed. Police on horseback charged with batons. 51 picketers and 72 policemen were injured. Other violent clashes also took place.

During the strike, 11,291 people were arrested. Most were for disturbing the peace or blocking roads while picketing. 8,392 were charged. Between 150 and 200 people were sent to prison. At least 9,000 miners were fired after being arrested, even if no charges were brought.

Picket lines failed to cause widespread power cuts, unlike in the 1970s. Electricity companies kept supplies going all winter. From September, some miners started returning to work, even in areas where the strike had been strong. This led to more tension and riots.

NACODS Union and the Strike

In April 1984, NACODS voted to strike, but not enough members voted yes. Most NACODS members did not cross picket lines in striking areas. They stayed home with full pay. When more miners started working in August, the NCB threatened to end this agreement. In September, NACODS voted to strike with 81% in favor.

The government then made some promises about how mine closures would be reviewed. This angered MacGregor. A deal was made that persuaded NACODS to call off their strike. The NUM rejected this deal. MacGregor later said that if NACODS had gone on strike, the NCB would likely have had to compromise.

Court Rulings and Legality

Early in the strike, the NCB got a court order to limit picketing. But the government did not want them to use it. They thought it would make miners more angry. Working miners, helped by activist David Hart, brought legal challenges. On May 25, a court ruled that the Nottinghamshire NUM could not say the strike was official. Similar rulings happened in Lancashire and South Wales.

In September, the High Court ruled that the NUM had broken its own rules. They called a strike without holding a national vote. The court did not order a vote. But it stopped the union from punishing members who crossed picket lines. Scargill called the ruling "another attempt by an unelected judge to interfere." He was fined, and the NUM was fined £200,000. When the union refused to pay, its assets were frozen.

A New Union Forms

The Nottinghamshire NUM officially supported the strike. But most of its members kept working. They felt the strike was against their union's rules. Many working miners felt the NUM was not protecting them from intimidation. In summer 1984, Nottinghamshire NUM members voted out leaders who supported the strike. The Nottinghamshire NUM then openly opposed the strike.

Working miners in Nottinghamshire and South Derbyshire formed a new union. It was called the Union of Democratic Mineworkers (UDM). It attracted members from many mines in England. The NCB encouraged the UDM. They announced that being an NUM member was no longer required for miners. This ended the "closed shop" system.

The Strike's Formal End

More and more miners returned to work from January 1985. Strikers were struggling to pay for food as union funds ran out. The strike officially ended on March 3, 1985. The South Wales area called for a return to work. They wanted sacked miners to be rehired. But the NCB refused. Only the Yorkshire and Kent regions voted against ending the strike.

One of the few things the NCB agreed to was to delay the closure of five pits. The issue of sacked miners was important in Kent. Kent NUM leader Jack Collins called those who went back to work "traitors." The Kent NUM continued picketing, delaying the return to work at many pits for two weeks.

At several mines, miners' wives groups gave out carnations, a symbol of heroes. Many miners marched back to work with brass bands. Scargill led a procession back to work at Barrow Colliery. But he stopped when he saw a picket line of Kent miners. He said, "I never cross a picket line," and turned away.

Public Opinion and Media Coverage

Many people felt sympathy for the miners. But there was not much public support for the strike itself. This was because of Scargill's methods. A Gallup poll in July 1984 showed 40% of people supported employers. 33% supported miners. By December 1984, 51% supported employers and 26% supported miners.

When asked if they approved of the miners' methods, 79% disapproved in July 1984. This rose to 88% disapproval by December 1984. Most people thought the miners' methods were irresponsible.

Newspapers like The Sun and the Daily Mail were very against the strike. Even newspapers that usually supported the Labour Party, like the Daily Mirror and The Guardian, became critical. This happened as the strike became more violent. The Morning Star was the only national newspaper that always supported the striking miners.

Some groups believed the media was purposely misrepresenting the strike. They felt the media used subtle attacks and biased facts. This had a big negative effect on the miners' cause.

Long-Term Impact of the Strike

During the strike, many mines lost their customers. There was also a lot of competition in the world coal market. More power was being produced using oil and gas. The government's policy was to reduce Britain's reliance on coal. They said coal could be imported more cheaply from other countries. The strike made the NCB close mines faster.

Tensions between striking miners and those who worked continued. Many miners who crossed picket lines left the industry. They were often avoided or attacked by other miners. Almost all of them in Kent had left the industry by April 1986. At Betteshanger Colliery, posters with photos and names of those who worked were put up.

The NCB was accused of abandoning the miners who worked. Abuse and threats continued. Requests for transfers to other mines were often denied. Miners felt discouraged and looked for jobs in other industries. Scargill's power in the NUM was challenged. His calls for another strike in 1986 were ignored.

In 1991, the South Yorkshire Police paid £425,000 in compensation to 39 miners. These miners had been arrested during the Orgreave clash. This was for "assault, false imprisonment and malicious prosecution."

The coal industry was sold to private companies in December 1994. Mine closures continued after the strike. By March 2005, only eight deep mines were left. The last deep coal mine in the UK, Kellingley Colliery, closed on December 18, 2015. This ended centuries of deep coal mining in Britain.

In 1994, Grimethorpe in South Yorkshire was named the poorest place in the country. It was also one of the poorest in the European Union.

In 2003, the smaller mining industry was more productive per worker than in France, Germany, and the United States. In 2016, many former mining areas voted to leave the European Union. Scargill, who supported leaving, said it was a chance to reopen closed coal mines.

In October 2020, the Scottish Government announced plans to pardon Scottish miners. These miners had been convicted of certain offenses during the strike.

Historical Views on the Strike

Many historians have tried to explain why the miners lost. They often focus on Scargill's decisions.

- Many experts say Scargill made a big mistake by not holding a national strike vote. This divided the NUM members. It also hurt the union's image with the public. The violence on the picket lines also made the government stronger.

- Robert Taylor described Scargill as an "industrial Napoleon." He said Scargill called a strike "at the wrong time" and on the "wrong issue." He used tactics that were "reckless" and had "inflexible demands."

In January 2014, Prime Minister David Cameron said that Arthur Scargill should apologize for how he led the union. Cameron said this when rejecting calls for the government to apologize for its actions during the strike.

Images for kids

See also

- Betty Heathfield

- Killing of David Wilkie

- Peter Heathfield

- Lesbians Against Pit Closures

- Music for Miners

- Public Order Act 1986

- Winter of Discontent

| Toni Morrison |

| Barack Obama |

| Martin Luther King Jr. |

| Ralph Bunche |