Winter of Discontent facts for kids

The Winter of Discontent was a tough time in the United Kingdom between late 1978 and early 1979. During this period, many workers went on strike because they wanted better pay. The government, led by Prime Minister James Callaghan and the Labour Party, was trying to limit pay rises to control inflation (when prices go up quickly).

These strikes caused a lot of problems for people. It was also one of the coldest winters in many years, with severe storms making things even harder.

One of the first big strikes was by workers at Ford in late 1978. They won a 17% pay increase, which was much higher than the 5% the government wanted to set as an example. After this, a strike by lorry (truck) drivers began. Then, many public workers, like gravediggers and rubbish collectors, also went on strike. This left rubbish piled up in streets, even in places like London's Leicester Square. Workers in the NHS (hospitals) also protested, meaning many hospitals could only take emergency patients.

The problems were deeper than just pay. There were disagreements within the Labour Party about how to run the country's economy. Many strikes started at a local level, and even national union leaders found it hard to stop them. More women and non-white workers were joining unions, especially in public services.

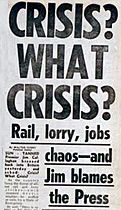

When Prime Minister Callaghan returned from a trip, he said there wasn't "mounting chaos." But the newspaper The Sun famously twisted his words into the headline "Crisis? What crisis?" This made him look out of touch. The leader of the Conservative Party, Margaret Thatcher, spoke about how serious the situation was. This helped her win the general election a few months later after Callaghan's government lost a vote.

Once in power, Thatcher's Conservative government passed new laws to limit the power of unions. They banned certain protest methods, like secondary picketing (protesting at a company that isn't directly involved in the dispute). The Winter of Discontent has been used in election campaigns ever since. The name "Winter of Discontent" comes from a line in William Shakespeare's play Richard III.

Contents

Why the Strikes Happened

The Winter of Discontent was caused by several problems that had been growing for over ten years.

Government Pay Limits

The government wanted to control inflation, so they tried to limit how much workers could get in pay rises. They had a "Social Contract" with the main union group, the Trades Union Congress (TUC). This meant unions agreed to voluntary limits on pay rises.

In 1978, the government set a strict limit of 5% for pay rises. Prime Minister Callaghan believed this was important to keep the economy stable and for his party to stay in power. However, union leaders warned that their members would not accept such a low limit. They wanted to be able to negotiate pay freely again.

Callaghan had planned to call an election in the autumn of 1978. But he decided not to, hoping the economy would be better in the spring if pay rises were kept low. This meant the 5% limit stayed in place. The government also said it would punish companies that broke the limit.

Changes in Unions

Between 1966 and 1979, unions in Britain changed a lot. More women and non-white workers joined unions. For example, 73% of new women workers joined a union during this time.

Workers also wanted more say in decisions, including when to strike. This meant that local union leaders and members often made decisions, sometimes without the national union leaders' full control.

Public Workers' Frustration

Many new union members worked for the government. About half of all British workers were in unions, but over 80% of public workers were. Their pay was often lower than private sector workers, and the government kept it low to set an example. Public sector unions felt their growing numbers weren't giving them enough power within the TUC.

This led to a fire brigade strike in 1977. Firefighters asked for a 30% pay rise. The government used the Army to cover for them. The TUC did not fully support the firefighters, trying to keep good relations with the government.

Conservatives' View on Unions

Margaret Thatcher became the leader of the Conservative Party in 1975. She believed that unions had become too powerful and were hurting Britain's economy.

Her advisors wrote a report called "Stepping Stones." It said that unions were causing problems like high unemployment and inflation. Thatcher wanted to reduce union power if her party won the election.

The Conservatives hired an advertising company, Saatchi & Saatchi, which created the famous "Labour Isn't Working" campaign. This campaign showed how many people were unemployed. The Sun newspaper, which used to support Labour, started supporting the Conservatives. They worked together to spread the message that unions were out of control.

Ford Workers' Strike

Even though it wasn't an official rule, the pay rise at Ford of Britain often set the standard for other private companies. Ford had done well that year and could afford to pay more. However, they were also a government contractor, so they offered a pay rise within the 5% limit.

Because of this, 15,000 Ford workers went on an unofficial strike in September 1978. This strike later became official and grew to 57,000 workers. It stopped the production of 115,000 vehicles.

After long talks, Ford eventually offered a 17% pay rise and accepted the government's penalties. Ford workers agreed to this on November 22.

Political Challenges

As the Ford strike started, the Labour Party had its annual meeting. A motion was passed that demanded the government stop interfering in pay talks. Prime Minister Callaghan accepted this defeat but said he would still fight inflation.

The government also had problems in Parliament. They had lost their majority of seats and needed support from other parties to pass laws.

After Ford settled for more than 5%, the government tried to make a new agreement with the TUC about pay. But the TUC leaders were divided, and no agreement was reached.

The government then announced penalties for Ford and other companies that broke the 5% pay limit. But the Conservatives and some Labour MPs voted against these penalties, meaning the government could no longer force private companies to stick to the limit.

Harsh Winter Weather Begins

A mild autumn suddenly turned very cold on November 25. Temperatures dropped, and snow began to fall. The cold weather continued through December, then got even worse at the end of the year.

Outside London, the effects were more severe. Some towns could only be reached by helicopter because roads were blocked by snow. Local councils struggled to clear roads. Trains were stuck, and petrol supplies were low because tanker drivers were also on strike. Many sports events were cancelled.

Lorry Drivers' Strike

With the government unable to enforce its pay limits, other unions started demanding bigger pay rises. Lorry drivers, represented by the TGWU union, demanded up to 40% more pay. They often worked very long hours for low wages.

The industry group for hauliers first said they would stick to the 5% limit. But as 1979 began, they suddenly offered 13%, hoping to avoid widespread strikes.

This offer had the opposite effect. Drivers, remembering a successful strike the previous winter, decided they could get even more by striking. On January 3, an unofficial strike of all TGWU lorry drivers began.

Petrol stations closed, and ports were blocked. The strikes became official on January 11. Since 80% of goods in the country were moved by road, essential supplies were at risk. Striking drivers stopped other trucks, and over a million workers were temporarily laid off.

In Kingston upon Hull, striking hauliers blocked the city's main roads, controlling what goods went in and out. Newspapers called it a "siege," and people worried about food shortages, leading to panic buying. The media often exaggerated the situation, which helped the Conservatives argue that unions were out of control.

The government considered using the Army to deliver fuel, but decided against it. They also allowed hauling companies to increase their offers to the strikers.

The TGWU union eventually agreed to let emergency supplies through. But local union officials decided what counted as an emergency, so practices varied across the country.

In Birmingham, violence broke out when 300 women working at a factory drove away striking lorry drivers who were trying to block a delivery. This incident made national news.

On January 29, lorry drivers in the South West accepted a deal for a pay rise of up to 20%. This deal became a model for settlements across the country.

After the drivers returned to work, some media outlets reported that the shortages had been more about fear than reality. But the fear of disruption had a big impact on the country's mood.

Public Sector Workers' Strikes

Bitter winter weather returned on January 22. Freezing rain and snow made roads impassable again.

Public sector unions had planned this day for a big strike. Since private sector workers had won large pay rises, public sector unions wanted to keep up. Train drivers and hospital staff also went on strike. The date was called the "Day of Action" by unions and "Misery Monday" by the media.

Many workers started striking without their union leaders' full approval. Ambulance drivers went on strike, and in some areas, they refused to answer 999 emergency calls. The Army had to step in to provide basic ambulance services. Hospital support staff also went on strike. By January 30, many NHS hospitals were only treating emergencies. The media reported that even cancer patients were being stopped from getting treatment, which caused public anger.

Gravediggers' Strike

In Liverpool, local rubbish collectors didn't want to be the first to strike. So, a union official asked the gravediggers and crematorium workers he represented to go first. They agreed, and their national union approved the strike.

The gravediggers had never struck before. The union official later said he knew the press would focus on it, and they did. With 80 gravediggers on strike, Liverpool City Council had to store bodies in a factory. At one point, 150 bodies were stored there, with 25 more added daily. This caused great public concern. A health official even talked about burial at sea as a hypothetical option, which caused alarm. The gravediggers eventually settled for a 14% pay rise after two weeks.

Waste Collectors' Strike

Many rubbish collectors had been on strike since January 22. Local councils ran out of places to store waste and started using public parks. Westminster City Council used Leicester Square in central London for piles of rubbish. This attracted rats, and the media nicknamed the area "Fester Square."

On February 21, the dispute with local authority workers was settled. They received an 11% pay rise, plus £1 per week, with the chance of more later.

End of the Strikes

By the end of January, 90,000 people were receiving unemployment benefits. The weather remained very cold. Many remote areas were still recovering from the snowstorms.

Prime Minister James Callaghan, who had strong ties to unions, was very upset by the strikes in essential services. He called the actions of the strikers "free collective vandalism."

The government negotiated with senior union leaders. On February 11, they reached an agreement. On February 14, as the weather began to warm up, the TUC leaders agreed to this plan. Strikes slowly began to stop after this point. In 1979, nearly 30 million working days were lost due to strikes, compared to 9 million in 1978.

The winter of 1979 was one of the coldest on record.

Effect on the Election

The strikes had a big impact on how people planned to vote. Before the strikes, Labour was ahead in polls. But by January 1979, the Conservatives were ahead, and by February, they had a large lead.

On March 1, votes were held on giving more power to Scotland and Wales. The vote in Wales was against it. In Scotland, a small majority voted for it, but it wasn't enough to meet the rules set by Parliament. Because the government didn't move forward with this, the Scottish National Party stopped supporting them. On March 28, the government lost a "no confidence" vote by just one vote, which led to a general election.

Margaret Thatcher had already spoken about her plans to limit union power. During the election campaign, the Conservative Party used images of the disruption from the strikes. One campaign video started with The Sun's "Crisis? What Crisis?" headline, showing piles of rubbish, closed factories, and blocked hospitals. Many people believe the strikes were a major reason for the Conservatives' big win in the election.

What Happened Next

After Thatcher won the election, she changed many laws about trade unions. One important change was that unions had to hold a vote among their members before calling a strike. As a result, strikes became much less common. By the time of the 1983 election, which the Conservatives also won easily, strikes were at their lowest level in 30 years.

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |