Enoch Powell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Enoch Powell

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

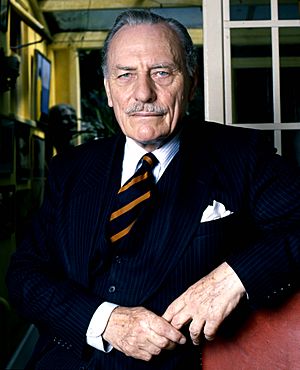

Portrait by Allan Warren, 1987

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Shadow Secretary of State for Defence | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 7 July 1965 – 21 April 1968 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Leader | Edward Heath | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Peter Thorneycroft | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Reginald Maudling | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Minister of Health | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 27 July 1960 – 18 October 1963 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Harold Macmillan | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Derek Walker-Smith | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Anthony Barber | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Financial Secretary to the Treasury | |||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 14 January 1957 – 15 January 1958 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | Harold Macmillan | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Henry Brooke | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Jack Simon | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

John Enoch Powell

16 June 1912 Birmingham, England |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 8 February 1998 (aged 85) London, England |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Warwick Cemetery, Warwick, England | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse |

Pamela Wilson

(m. 1952) |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | British Army | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service | 1939–1945 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Brigadier | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Unit |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars | Second World War

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Awards | Member of the Order of the British Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Education |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific career | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Institutions | |||||||||||||||||||||

John Enoch Powell (16 June 1912 – 8 February 1998) was a well-known British politician. He was a Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) from 1950 to 1974. He also served as Minister of Health from 1960 to 1963. Later, he became an MP for the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) from 1974 to 1987.

Before becoming a politician, Powell was a brilliant classical scholar. During the Second World War, he worked in staff and intelligence roles, reaching the high rank of brigadier. He also wrote poetry and many books about ancient history and politics.

Powell became very famous for a speech he gave on 20 April 1968, often called the "Rivers of Blood" speech. In this speech, he talked about his concerns regarding immigration to the UK, especially from the Commonwealth. He also spoke against a new law, the Race Relations Act 1968, which aimed to stop discrimination. This speech caused a lot of debate and criticism, even from members of his own party. The leader of the Conservative Party, Edward Heath, removed Powell from his position as Shadow Defence Secretary the day after the speech.

However, many people in the UK supported Powell's views. Polls at the time showed that a large number of people (between 67% and 82%) agreed with him. Some of his supporters believed that his popularity helped the Conservatives win the 1970 general election. Powell later left the Conservative Party and was elected as an MP for the Ulster Unionist Party in October 1974. He continued to represent the South Down area until he lost his seat in the 1987 general election.

Contents

Growing Up

John Enoch Powell was born in Birmingham, England, on 16 June 1912. He was the only child of Albert Enoch Powell, a primary school headmaster, and Ellen Mary. As a child, he was known as "Jack" because his mother did not like his first name. When he was three, people nicknamed him "the Professor" because he loved to describe the stuffed birds in his home.

The Powell family had Welsh roots. They were not rich, but they were comfortable. Their home had a library, and Enoch loved to read, especially history books. From a young age, he showed a strong interest in learning. He would even give lectures to his parents on Sundays about the books he had read.

Powell went to a small school until he was eleven. Then, he attended King's Norton Grammar School for Boys for three years. In 1925, at age thirteen, he won a scholarship to King Edward's School, Birmingham. The memory of the First World War was strong at his school, as many teachers had fought in it. This made Powell believe that Britain and Germany would fight again.

Powell was very good at classical studies. His mother taught him Greek in just over two weeks during a Christmas break. By the next school term, he was fluent in Greek, a level most students took two years to reach. He quickly became the top student in classics. His classmates remembered him as very smart and focused.

He won many prizes for his studies. At fourteen, he started translating Herodotus' Histories. He entered the sixth form two years earlier than other students. His teachers were very impressed by his dedication and knowledge. Powell also learned German and began reading German books, which influenced his thoughts on religion. He also read important philosophical works that shaped his views.

In December 1929, at seventeen, he won a top scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge. He was so fast at exams that he often left early. For one Greek paper, he translated text in two different ancient Greek styles and then added notes.

University Life

Powell studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, from 1930 to 1933. He spent most of his time studying, sometimes reading from early morning until late at night. He was known as "The Hermit of Trinity" because he was so focused on his work. At eighteen, his first academic paper was published. He started using his middle name, Enoch, to avoid confusion with another scholar.

He won the Craven scholarship, a very important award, early in his second term. This was only the second time a first-year student had won it since it began in 1647. At Cambridge, he was greatly influenced by the poet A. E. Housman, a Latin professor. Powell admired Housman's sharp mind and careful way of analyzing texts.

Powell won many other awards and graduated with top honors. A Cambridge scholar called him "the best Greek scholar since Porson". Besides his studies at Cambridge, Powell also learned Urdu at the School of Oriental Studies in London. He hoped to become Viceroy of India one day, and he believed knowing an Indian language was important. He later learned other languages, including Welsh, modern Greek, and Portuguese.

Academic Career

After graduating, Powell stayed at Trinity College as a fellow. He studied ancient Latin writings and produced academic works in Greek and Welsh. He used a scholarship to travel to Italy, where he read Greek manuscripts in libraries and learned Italian.

Powell was convinced that war with Germany was coming after Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933. He told his father in 1934 that he wanted to join the army on the first day of war. He was deeply upset by events in Germany, which made him lose his admiration for German culture.

In 1937, Powell published his first book of poems, First Poems. They were influenced by Housman and praised for their clear and concise style. His second book of poems, Casting Off, and Other Poems, came out in 1939. These poems often reflected his thoughts on the coming war.

In 1937, at age 25, he became Professor of Greek at the University of Sydney in Australia. He was the youngest professor in the British Empire. One of his students was Gough Whitlam, who later became Prime Minister of Australia. Powell revised an important edition of Thucydides' Historiae in 1938. His most lasting contribution to classical studies was his Lexicon to Herodotus, published the same year. This lexicon is still considered a very important and accurate work.

Soon after arriving in Australia, Powell told the university's vice-chancellor that war would soon begin in Europe and that he would return home to join the army. He strongly disliked Britain's policy of appeasement towards Germany. In 1938, he visited Germany and met with anti-Nazi individuals, helping one German-Jewish scholar get a visa to escape. When war broke out, Powell immediately returned to the UK.

Military Service

In October 1939, Powell joined the Royal Warwickshire Regiment as a private soldier. He had trouble enlisting because the War Office wasn't looking for men without military training during the "Phoney War". So, he pretended to be Australian, as Australians were allowed to enlist right away. He bought a copy of Carl von Clausewitz's On War in German and read it every night.

Powell was quickly promoted. He passed his officer training at the top of his class. In May 1940, he became a second lieutenant and was soon transferred to the Intelligence Corps. He was promoted to captain and then major. He even taught himself Portuguese to read poetry. He also used his knowledge of Russian to translate a parachute training manual.

In October 1941, Powell was sent to Cairo. He became secretary to the Joint Intelligence Committee, Middle East, doing work usually done by more senior officers. He was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in August 1942. In this role, he helped plan the Second Battle of El Alamein, a major battle in World War II. He was later awarded the Member of the Order of the British Empire for his military service.

It was in Algiers that Powell began to distrust the United States. He believed that one of America's goals was to weaken the British Empire. This suspicion of American foreign policy stayed with him throughout the war and into his political career.

After the Axis forces were defeated at El Alamein, Powell wanted to go to the Far East to fight against the Japanese. He was posted to the British Imperial Indian Army in Delhi in August 1943 as a lieutenant-colonel in military intelligence. He quickly learned about India, writing that he "soaked up India like a sponge".

Powell was appointed Secretary to the Joint Intelligence Committee for India and Louis Mountbatten's South East Asia Command. He was involved in planning an attack on Akyab off the coast of Burma. He continued to learn Urdu and had a goal of editing a famous Urdu poem. He also dreamed of becoming Viceroy of India.

Powell began the war as the youngest professor in the British Empire and ended it as a brigadier. He was one of only two men in the entire war to rise from private to brigadier. He was offered a permanent position in the Indian Army, but he turned it down. Powell never saw direct combat and felt a sense of guilt for surviving. He once said he would have liked to have been killed in the war.

Entering Politics

After the war, Powell joined the Conservative Party. He worked for the Conservative Research Department. His dream of becoming Viceroy of India ended in February 1947 when Prime Minister Clement Attlee announced that India would soon become independent. Powell was so shocked that he walked the streets of London all night. This event made him strongly believe that Britain should give up its empire entirely.

Becoming an MP

After trying unsuccessfully in a by-election in 1947, Powell was elected as a Conservative MP for Wolverhampton South West in the 1950 general election.

On 16 March 1950, Powell gave his first speech in Parliament, talking about defence. In 1953, he spoke against the Royal Titles Bill. He believed it weakened the idea of the British Crown as a single, unified power over all its territories. He also disliked the removal of the word "British" from the title, feeling it made Britain seem less important. He argued that the new title, "Head of the Commonwealth," was not truly meaningful because some countries in the Commonwealth had stopped being loyal to the Crown. Powell considered this speech one of his best.

In 1953, Powell joined the executive committee of the 1922 Committee, a group of Conservative MPs. He was also part of a committee that reviewed party policy for the general election. Powell was initially against removing British troops from the Suez Canal. However, after the troops left and Egypt took control of the Canal, he opposed the attempt to retake it. He believed Britain no longer had the resources to be a major world power.

In and Out of Government

Junior Housing Minister

On 21 December 1955, Powell became the parliamentary secretary at the Ministry of Housing. He worked on laws related to housing, including those for clearing slums and providing fair compensation for homes taken by the government.

In 1956, Powell attended a meeting about immigration control. He suggested that limiting immigration might be necessary in the future, but he felt the time had not yet come for such a big change. He also supported a bill that ended wartime rent controls.

Financial Secretary to the Treasury

In January 1957, Powell was offered the important job of Financial Secretary to the Treasury, which is the Chancellor of the Exchequer's deputy. He resigned from this position in January 1958, along with the Chancellor, Peter Thorneycroft. They resigned to protest government plans for increased spending. Powell believed that too much government spending led to inflation, which makes money worth less. He was a strong supporter of controlling the money supply and allowing free markets to work.

Powell's ideas about controlling the money supply and promoting free markets were seen as very unusual at the time. He suggested privatizing the Post Office and the telephone network many years before it actually happened. He also believed the Conservative Party should be more modern and business-like, moving away from old traditions.

Hola Massacre Speech

On 27 July 1959, Powell gave a powerful speech about the Hola massacre in Kenya. Eleven prisoners had died in a camp there. Powell strongly disagreed with anyone who said these prisoners were "sub-human." He argued that it was wrong to judge people in such a way. He also said that Britain must always uphold its highest standards of justice, no matter where in the world its actions took place. This speech was praised by many, including Denis Healey, who called it "the greatest parliamentary speech I ever heard."

Minister of Health

Powell returned to government in July 1960 as Health Minister. He became a member of the Cabinet in 1962. During his time as Health Minister, he created the 1962 Hospital Plan. He also started a discussion about improving psychiatric hospitals, suggesting they should be replaced by smaller units in general hospitals. This idea later led to the "Care in the Community" initiative in the 1980s. Powell believed this new approach would be more humane but would also cost more money.

Some people later claimed that Powell, as Health Minister, recruited immigrants from the Commonwealth to work in the National Health Service (NHS). However, the Minister of Health was not responsible for hiring staff; this was done by local health authorities. Powell's biographer and other officials have stated that this claim is not true. Powell did welcome immigrant nurses and doctors for training, hoping they would return to their home countries afterwards. He was concerned about the impact of immigration on the NHS and wanted stronger controls on Commonwealth immigration.

The 1960s

Leadership Elections

In October 1963, Powell and some other politicians tried to convince Rab Butler not to serve under Alec Douglas-Home as Prime Minister. Powell and Iain Macleod refused to join Douglas-Home's Cabinet because they were unhappy with how the new leader was chosen. Powell also reportedly disagreed with Douglas-Home's views on Africa.

During the 1964 general election, Powell stated that strict control over immigration was necessary to avoid "a 'colour question' in this country." After the Conservatives lost the election, Powell returned to the front bench as Transport Spokesman. In July 1965, he ran in the first-ever party leadership election but received few votes. Edward Heath won and appointed Powell as Shadow Secretary of State for Defence.

Shadow Defence Secretary

In October 1965, Powell gave a speech outlining a new defence policy. He suggested that the UK should give up its old global military commitments and focus on being a European power, allied with Western European countries against threats from the East. He also defended Britain's nuclear weapons.

Powell's speech worried the Americans, who wanted Britain to maintain military presence in South-East Asia due to the Vietnam War. Powell claimed that the British government had plans to send forces to Vietnam and that Britain was acting like "an American satellite." He later said that if his statements prevented Britain from sending troops to Vietnam, it was "the greatest service I have performed for my country."

In 1967, Powell spoke against the immigration of Kenyan Asians to the UK. This was after Kenya's leader, Jomo Kenyatta, introduced policies that led to many Asians leaving that country.

A National Figure

'Rivers of Blood' Speech

Enoch Powell was known for his powerful speaking skills. On 20 April 1968, he gave a speech in Birmingham that became very famous. In this speech, he warned about what he believed would happen if there was continued large-scale immigration from the Commonwealth to the UK.

The speech caused a huge stir. The Times newspaper called it "an evil speech," saying it was the first time a serious British politician had directly appealed to racial hatred in post-war Britain. The main political issue Powell addressed was the new Race Relations Act 1968. This law aimed to stop discrimination based on race in areas like housing. Powell found this law offensive.

In his speech, Powell shared a letter from a constituent in Wolverhampton. The letter described the difficult experiences of an elderly woman who felt isolated in her neighborhood.

The day after the speech, Edward Heath, the Conservative Party leader, removed Powell from his position in the Shadow cabinet. Powell never held another senior political job. However, Powell received nearly 120,000 letters, mostly positive. A Gallup poll in April showed that 74% of people agreed with his speech. Many felt that Powell was the first politician who truly listened to their concerns.

Three days after the speech, on 23 April, about 1,000 dockers marched in London to protest against Powell's dismissal. They carried signs saying, "we want Enoch Powell!" and "Enoch here, Enoch there, we want Enoch everywhere." The next day, other workers also showed their support. Some politicians, like Michael Heseltine, later said that if Powell had run for leader of the Conservative party after this speech, he would have won easily.

Economic Ideas

On 11 October 1968, Powell gave a speech in Morecambe about the economy. He proposed radical free-market policies, which later became known as the 'Morecambe Budget'. He suggested ways to cut income tax and abolish other taxes without reducing spending on defence or social services. He believed this could be done by ending losses in nationalized industries, privatizing profitable state businesses, and cutting foreign aid and other government grants. These ideas were very different from the economic policies of the time.

House of Lords Reform

In mid-1968, Powell's book The House of Lords in the Middle Ages was published. He strongly opposed government plans to reform the House of Lords, the second chamber of the UK Parliament. He argued that the reforms were "unnecessary and undesirable." He believed the House of Lords got its authority from its long history, not from elections. He also said there was no widespread public demand for reform.

Powell gave many speeches against the bill to reform the Lords. In early 1969, the Labour government withdrew the bill. Powell's biographer called this "perhaps the greatest triumph of Powell's political career."

In 1969, Powell also spoke out against the United Kingdom joining the European Economic Community (EEC), which was a group of European countries working together. He believed it would threaten Britain's independence.

Leaving the Conservative Party

A Gallup poll in February 1969 showed Powell was the "most admired person" in British public opinion.

In 1970, Powell argued that tactical nuclear weapons were "an unmitigated absurdity" and that Britain should focus on its conventional forces.

The 1970 general election was unexpectedly won by the Conservatives. Some of Powell's supporters believed he helped them win. However, the victory was not good for Powell, who was unhappy with the party's direction.

Powell had always been against Britain joining the European Economic Community. He believed it would take away Parliament's power and threaten Britain's existence as a nation. This strong belief made him a fierce opponent of Edward Heath, who was very pro-European. Powell voted against the government on every occasion related to the European Communities Bill. After three years of campaigning, when he lost this fight, he decided he could no longer be part of a Parliament that he felt was no longer truly independent.

In 1972, a poll showed Powell was the most popular politician in the country. He almost resigned from the Conservative Party but decided to stay due to concerns about new immigration from Uganda. However, on 23 February 1974, just five days before a general election, Powell made a dramatic decision. He announced he would not support his party. He said the Conservatives had taken the UK into the EEC without public support and had broken other promises. He urged people to vote for the Labour Party instead.

This call to vote Labour surprised many of Powell's supporters. He explained that he was born a Tory and would die a Tory, but he felt the Conservative Party had lost its way. He believed that many Labour supporters were "quite good Tories" in their views. Powell did not watch the election results, but when he saw the headline that Heath's gamble had failed, he was very pleased. He felt he had gotten "revenge on the man who had destroyed the self-government of the United Kingdom." The election resulted in a hung parliament, with Labour winning slightly more seats. Many believed Powell's actions contributed to the Conservative loss.

Ulster Unionist MP

1974–1979

In a new general election in October 1974, Powell returned to Parliament as an Ulster Unionist MP for South Down in Northern Ireland. He continued to urge people to vote Labour because of their policy on the EEC.

Powell had visited Northern Ireland often since 1968. He strongly supported the Ulster Unionists who wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom. He believed Northern Ireland should be fully integrated into the UK, without its own devolved government. He was also against more extreme forms of loyalism.

After the Birmingham pub bombings in November 1974, the government passed the Prevention of Terrorism Act. Powell warned against passing laws too quickly that affect people's basic freedoms. He argued that terrorism was a form of warfare that could only be stopped if the attackers knew they could not win.

When Margaret Thatcher became leader of the Conservative Party in 1975, she refused to offer Powell a place in her Shadow Cabinet. She said he had "turned his back on his own people" by leaving the Conservative Party. Powell replied that she was right to exclude him, stating he would not rejoin the Conservatives until they changed their views significantly.

During the 1975 referendum on Britain's membership in the EEC, Powell campaigned for a 'No' vote. However, the public voted 'Yes' by a large margin.

Powell believed that the only way to stop the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) was for Northern Ireland to be treated exactly like any other part of the United Kingdom.

He continued to criticize the United States, believing they wanted Britain to give up Northern Ireland to an all-Irish state. He thought the US wanted Ireland to join NATO, and that Northern Ireland was a barrier to this.

Although he voted with the Conservatives to bring down the Labour government in March 1979, Powell was not happy when Margaret Thatcher won the May 1979 election. He feared she would go back on her promises, just as Heath had done.

1979–1982

After a riot in Bristol in 1980, Powell warned that the growing immigrant population could lead to major conflict, which he described as "civil war." He criticized those who said it was "too late to do anything" and suggested that a large-scale re-emigration was the solution.

In the 1980s, Powell began to support unilateral nuclear disarmament, meaning Britain should get rid of its nuclear weapons even if other countries did not. He argued that Britain's nuclear deterrent was not truly independent and that it tied the UK to the United States' nuclear strategy. He believed nuclear weapons would not prevent an invasion and were not worth keeping.

In March 1981, Powell spoke about a "conspiracy of silence" regarding the growth of the immigrant population. He warned of future violence and called for "re-emigration." After riots in Brixton and Toxteth, he argued that these events were due to the growing non-white population in inner cities, not just economic problems. He disagreed with the Scarman Report, which said alienation was due to economic disadvantage, arguing it was because the communities were "alien."

Falklands Conflict

When Argentina invaded the Falkland Islands in April 1982, Powell received secret briefings. On 3 April, he stated in Parliament that while the issue should go to the United Nations, Britain should take strong action immediately. He famously told Prime Minister Thatcher, "The Prime Minister... will learn of what metal she is made." This statement reportedly strengthened Thatcher's resolve.

Powell supported the military action to retake the Falklands. He argued that Britain was defending its own territory and people. He also criticized the United Nations' call for a "peaceful solution," saying it would reward the aggressor. He believed that the right to self-defence existed before the UN and that the UN's actions were "disgraceful."

Powell also used the Falklands War to criticize the United States. He believed the US wanted the Falklands to be under American influence and that the US was trying to weaken the British Empire. He urged Britain to assert its own position in the world, independent of American influence.

1983 General Election

In the 1983 general election, Powell faced a candidate from the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) in his constituency. Ian Paisley, the DUP leader, called Powell "a foreigner and an Anglo-Catholic."

Powell also spoke against the stationing of US cruise missiles in the UK. He believed the United States had an "obsessive sense of mission" and a false view of international relations. He argued that Britain should not be tied to American foreign policy.

1983–1987

In 1984, Powell made unproven claims that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) had murdered Earl Mountbatten and that the assassinations of MPs Airey Neave and Robert Bradford were directed by elements in the US government. He suggested these actions were to prevent Ulster from being fully integrated into the UK. Margaret Thatcher rejected these claims.

In 1985, after race riots in London and Birmingham, Powell repeated his warnings of ethnic conflict. He again called for a government program of repatriation.

Powell strongly disagreed with Margaret Thatcher's support for the Anglo-Irish Agreement in November 1985. He publicly accused her of "treachery." In protest, Powell and other Unionist MPs resigned their seats and then narrowly won them back in by-elections.

In 1986, Powell had a notable exchange with a new MP, Seamus Mallon. Mallon quoted a philosopher, and Powell immediately corrected him on the quote. They went to the library to check, and Mallon was found to be correct.

In 1987, Powell believed that Thatcher's visit to the Soviet Union showed a big change in Britain's foreign and defence policy. He argued that the idea of nuclear deterrence was being challenged by new developments.

Powell lost his seat in the 1987 general election by a small number of votes. This was mainly due to changes in the constituency boundaries and population. His opponent, Eddie McGrady, paid tribute to Powell. Powell said he would always have affection for Northern Ireland. He was offered a life peerage, which is a seat in the House of Lords for life, but he declined it. He felt it would be hypocritical to accept, as he had opposed the law that created life peerages.

After Parliament

1987–1992

After leaving Parliament, Powell continued to be a public figure. He criticized the Special Air Service (SAS) shootings of IRA members in Gibraltar in 1988. He also wrote that Russia's new foreign policy under Mikhail Gorbachev meant "the death and burial of the American empire."

In December 1988, Powell repeated his warning of civil war in the UK due to immigration. He said the solution was large-scale repatriation.

In 1989, Powell made a BBC program about his visit to Russia. He believed that a people who had suffered so much in war would not willingly start another. He also argued that the UK should form an alliance with the Soviet Union because of German reunification.

Powell strongly supported Margaret Thatcher's growing opposition to a European currency and further European integration. He believed she was defending Britain's independence. In 1990, he said that if the Conservatives focused on a "British card" (nationalism) in the next election, they could win. He praised Thatcher for standing up for Britain's self-government.

When Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990, Powell argued that Britain should not go to war. He believed it was not in Britain's national interest to intervene in the Middle East.

When Thatcher faced a challenge for the leadership of the Conservative Party in November 1990, Powell said he would rejoin the party if she won. He wanted to support her and national independence. However, Thatcher resigned, and Powell never rejoined the Conservatives. He believed that while the "battle has been lost, but not the war" for British independence.

In December 1991, Powell stated that the breakup of Yugoslavia did not affect the UK's safety. He believed Britain should have a foreign policy that suits its unique position as an island nation in Europe. In the 1992 general election, Powell campaigned for Nicholas Budgen, praising his opposition to the Treaty of Maastricht, which aimed for closer European integration.

Final Years

In late 1992, at age 80, Powell was diagnosed with Parkinson's disease. In 1994, he published a book called The Evolution of the Gospel. He continued to write articles, stating that the British people would not give up their right to govern themselves.

In 1993, on the 25th anniversary of his "Rivers of Blood" speech, Powell wrote that the concentration of immigrant communities in cities would lead to "communalism" and affect the electoral system. He supported Alan Sked of the Anti-Federalist League (which later became the UK Independence Party) in a by-election.

Powell continued to speak out against European integration. He believed that Europe had "destroyed one Prime Minister and will destroy another Prime Minister yet." He argued that Britain was "waking from the nightmare of being part of the continental bloc" and rediscovering its connection to the wider world.

In his final years, he wrote occasional articles and participated in a BBC documentary about his life. In April 1996, he wrote that Britain could still reclaim its power from Europe. In October, he gave his last interview, saying that his ideas about national independence were now widely accepted. When Labour won the 1997 general election, Powell told his wife, "They have voted to break up the United Kingdom."

Death

Enoch Powell died on 8 February 1998, at the age of 85, in London. His study of the Gospel of John was unfinished.

His body, dressed in a brigadier's uniform, was buried in Warwick Cemetery, Warwickshire. Over 1,000 people attended his funeral. Many politicians, including former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, paid tribute to him. Thatcher said, "There will never be anybody else so compelling as Enoch Powell. He was magnetic." Even his political rival, Labour MP Tony Benn, attended, saying, "he was my friend."

Former Labour Party leader Tony Blair also paid tribute, saying that Powell was "one of the great figures of 20th-century British politics, gifted with a brilliant mind." He acknowledged Powell's strong convictions and sincerity, even if people disagreed with his views. Powell was survived by his wife and two daughters.

Personal Life

Powell was a talented linguist. He spoke German, French, Italian, Modern Greek, and Hindi/Urdu. He could also read Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, Welsh, Ancient Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and Aramaic.

Despite being an atheist earlier in his life, Powell became a devoted member of the Church of England. He believed he heard the church bells of St Peter's Wolverhampton calling him to faith. He later became a churchwarden at St. Margaret's, Westminster.

On 2 January 1952, Powell married Pamela Wilson. They had two daughters, Susan and Jennifer.

Powell believed that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon was not the true author of Shakespeare's plays and poems. He argued that the plays showed a deep understanding of politics and power that the traditional Shakespeare would not have had.

Powell was also a poet, with four collections published. He translated Herodotus' Histories and wrote many other academic works. His political writings often criticized his own party. When asked about his achievements, he said it was hard for anyone to know how the world changed because they were in it. In 2002, he was voted 55th in a BBC poll of the 100 Greatest Britons of all time.

Pamela Powell, his wife, passed away in November 2017, 19 years after her husband.

Political Views

Powell's "Rivers of Blood" speech in 1968 led to much debate. A poll taken after the speech showed that 74% of Britons agreed with his views on immigration. However, some, like Bishop Wilfred Wood, believed Powell's speech made racist views seem acceptable to some people.

Some people claimed Powell was far-right or fascist. However, his supporters pointed out that he voted for social reforms like homosexual law reform and against the death penalty, which were unpopular among many Conservatives at the time.

Powell had concerns about immigration from the early 1960s. He believed that the UK's citizenship laws needed to change to control immigration. He also expressed concerns about the impact of immigration on communities in his constituency.

In 1970, Tony Benn criticized Powell's approach to immigration, comparing it to Nazism. Powell responded by saying he had fought against Nazism in World War II. He also argued that a large influx of people from any country, even Germany or Russia, would cause serious problems for the UK.

Powell stated that his views were not based on genetics or race. He said he did not judge people based on their origins. Friends recalled that he enjoyed speaking Urdu with Indian restaurant owners and once refused to stay at a club that did not allow an Indian general to stay there.

However, some people felt that Powell's language, especially in the "Rivers of Blood" speech, could be used to promote racial prejudice. Powell himself said that it was "difficult, for a non-white person to be British."

Throughout his political life, Powell was often critical of "the Establishment." He was known for making speeches that challenged the government. He refused a life peerage, believing it would be hypocritical since he had opposed the law that created them.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Enoch Powell para niños

In Spanish: Enoch Powell para niños