St Peter's Collegiate Church facts for kids

Quick facts for kids St Peter's Collegiate Church, Wolverhampton |

|

|---|---|

St Peter's Collegiate Church

|

|

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Churchmanship | High Church |

| Website | St. Peter's Collegiate Church |

| History | |

| Dedication | Saint Peter |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Central Wolverhampton |

| Diocese | Lichfield |

| Province | Canterbury |

St Peter's Collegiate Church is a very old church in Wolverhampton, England. For hundreds of years, it was a special "royal chapel." This meant it was directly connected to the King or Queen, not the local bishop or even the Archbishop of Canterbury.

This church was super important for the growth of Wolverhampton. Much of the town actually belonged to its leader, called the Dean. Until the 1700s, it was the only church in Wolverhampton. Its influence reached far into the nearby areas, with smaller churches in many towns and villages.

Since 1848, St Peter's has been part of the Anglican Church of England. It's a Grade I listed building, meaning it's very important historically and architecturally. Most of it was built in the 1400s. Even though it's not a cathedral, it has a strong tradition of choir music, like a big cathedral. The famous Father Willis organ is a highlight. It was restored in 2019.

Contents

History of St Peter's Church

St Peter's Church started a very long time ago, in the Anglo-Saxon period. For centuries, it was a "collegiate church." This meant it was run by a group of priests called a "college," led by a Dean and prebendaries. It also had strong ties to the royal family. In 1480, it officially became a Royal Peculiar, meaning it was under the direct control of the monarch.

This special status brought both pride and money to the church and town. But it also meant the church was sometimes controlled by the King or Queen, rather than serving its local community. Often, the leaders (deans) were absent or corrupt. The college faced many legal battles and was even shut down and reopened three times! Finally, in 1846-1848, it was fully dissolved. This allowed St Peter's to become a regular parish church, serving the people of Wolverhampton.

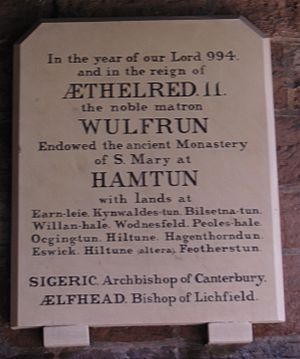

Early Beginnings: Wulfrun's Gift

The story of St Peter's College begins with Lady Wulfrun. Around 994 AD, she gave land to a church in a place called Hampton. This church was originally dedicated to St Mary. The name "Wolverhampton" comes from "Wulfrun's Hampton."

Wulfrun's gift was meant to help the church and its priests. She gave ten "hides" of land (an old measure of land) in Hampton. She also gave land in other places like Upper Arley, Bilston, Willenhall, and Wednesfield. These gifts helped support the church and its work.

The church was run by a group of secular clergy (priests who were not monks). They were responsible for caring for people across a large area. This type of church, called a "minster," was common in Anglo-Saxon England.

Norman Conquest and Royal Ties

After the Norman Conquest in 1066, things changed for the church. William the Conqueror gave the church to his own chaplain, Samson. This started a long and important connection between the church and the English Crown.

The Domesday Book (a great survey of England in 1086) shows that the church's lands were managed differently. Some lands were lost, but new ones were gained. The church's lands were often surrounded by royal hunting forests, which limited farming.

Later, King Henry I (1100–1135) gave a large gift to the church. This was to set up a special prayer service for himself and his parents. Around this time, the church's dedication changed from St Mary to St Peter.

Times of Trouble and Change

During a period of civil war called The Anarchy (1135–1154), the church faced many challenges. It was even taken over by Roger, Bishop of Salisbury, a powerful figure. But the canons (priests) of the church fought back, even appealing to the Pope.

When Henry II became king in 1154, he strongly supported the church. He called it "my chapel" and gave it back all its old rights and freedoms. He also made sure it didn't have to pay royal taxes. This confirmed its special status as a royal chapel, separate from the local bishop.

Dissolution and Restoration

Around 1202, the Dean, Peter of Blois, tried to reform the college. He complained to Pope Innocent III that the priests were corrupt and too closely related. He suggested turning the college into a Cistercian monastery. King John agreed, and for a short time, the college was dissolved.

However, when Archbishop Hubert Walter, who was helping with the plan, died in 1205, King John changed his mind. He quickly appointed a new Dean, Henry, and restored the college to its old ways. This meant the church went back to being a college of priests, not a monastery.

Growth and Wealth

In the 1200s, leaders like Giles of Erdington (Dean around 1224) worked hard to make the college rich and powerful. Erdington was a skilled lawyer and a judge for King Henry III. He made deals with the local bishop to protect the church's independence. He also fought for the church's economic interests.

In 1258, Erdington got the right for the deanery to hold a weekly market and a yearly fair in Wolverhampton. These events took place right at the church steps, bringing lots of trade and money to the town and church. The church also gained more control over its lands and tenants.

The next Dean, Theodosius de Camilla, was an Italian relative of a Pope. He was often away on royal business, but he also strongly defended the church's rights. He fought against the Archbishop of Canterbury, who wanted to control the royal chapels. Theodosius won, showing how powerful the church's royal connections were.

By the late 1200s, St Peter's was at its peak of wealth. However, many of its leaders were absent, and the church's spiritual standards were not always high.

Neglect and Revival

In the 1300s, the church faced hard times. Deans often neglected the buildings and even stole from the church's assets. For example, Dean Hugh Ellis (1328–1339) was accused of selling off valuable church property and letting the buildings fall apart. Kings had to order investigations into these problems.

Despite this neglect, local people continued to support the church. They made donations and left money in their wills to fund priests and services. Special groups, like the "wardens of the light," were formed to care for the church. St Mary's Hospital, an almshouse (a place for poor people) and chantry (a place for prayers), was founded in 1392 through the efforts of generous local people.

Things started to improve in the 1400s. Dean John Barningham (1437–1457) began rebuilding the church. He made sure records were kept and people were held accountable. Much of the church you see today was shaped during this time.

In 1480, a very important change happened. King Edward IV formally joined the deanery of Wolverhampton with St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, the King's own chapel. This made St Peter's a true Royal Peculiar, directly under the monarch's control.

Reformation and Civil War

The Reformation in the 1500s brought big changes. In 1547, King Edward VI dissolved the college. It became a simple parish church. However, the deans and canons continued to receive pensions. Much of the church's land was leased out to powerful local families, like the Levesons.

When Queen Mary came to power, she restored the college in 1553. She wanted to bring back the old Catholic ways. Even though Queen Elizabeth I later led England back to Protestantism, she confirmed the college's restoration in 1564. This meant the old system, with often absent deans, continued.

In the 1600s, there was a lot of religious conflict. Puritans complained about the church's practices and the absent clergy. During the English Civil War (1642–1651), St Peter's suffered damage. Parliamentary soldiers attacked the church, and royalist soldiers destroyed all its records.

Under the Commonwealth (1649–1660), the college was again abolished. St Peter's became a parish church with Puritan ministers. However, the Leveson family, who had leased the church lands, were royalists. Their lands were seized by Parliament, but they fought to get them back. This left the church and its ministers with very little money.

Decline and Modernization

When King Charles II was restored in 1660, the college at St Peter's was also restored. But it still struggled financially. The lost records made it hard to prove ownership of lands. The church tried for centuries to get its property back from the Leveson family, but without success.

As Wolverhampton grew, St Peter's became very crowded. In the 1700s, new "chapels of ease" were built in Wednesfield, Willenhall, and Bilston to help. In 1755, St John's Church, Wolverhampton was built in Wolverhampton itself. This ended St Peter's monopoly as the only church in town.

The old system of the Royal Peculiar, with its absent deans, was no longer working for the growing town. In 1811, some reforms were made, but they weren't enough. Finally, in 1848, a new law called the Wolverhampton Church Act completely abolished the ancient college. All its assets went to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, who manage Church of England finances.

St Peter's became a regular parish church within the Diocese of Lichfield, with its own Rector. All the smaller chapels also became separate parish churches. This change helped the church better serve the people of Wolverhampton.

Timeline of St Peter's Church

- 994: Lady Wulfrun gives land to the Church of St Mary at Heantune (Wolverhampton).

- 1066: After the Norman Conquest, the church is given to Samson, a royal chaplain.

- 1152-54: The church becomes a royal chapel, independent of the local bishop, and is dedicated to St Peter.

- 1203-05: The college is dissolved due to corruption, but then restored.

- 1258: The church gains the right to hold a weekly market and annual fair.

- 1440: The nave roof is raised, and the church building is reshaped.

- 1450: The stone pulpit is built.

- 1479: King Edward IV unites the Deaneries of Wolverhampton and Windsor, making St Peter's a Royal Peculiar.

- 1547: The Reformation leads to the college being dissolved and becoming a parish church.

- 1553: Queen Mary restores the college.

- 1635: Dean Christopher Wren consecrates a new altar, causing controversy with Puritans.

- 1642-43: The church is damaged during the English Civil War, and its records are destroyed.

- 1646-60: Under the Commonwealth, St Peter's is a parish church with Puritan ministers.

- 1755: The building of St John's Church ends St Peter's monopoly in the town.

- 1840: The Cathedrals Act declares the deanery abolished upon the death of the current dean.

- 1846: Dean Hobart dies, and the deanery is suppressed.

- 1848: The college is fully wound up. St Peter's becomes a parish church within the Lichfield Diocese, with its own Rector.

Architecture of St Peter's

St Peter's Church is made of red sandstone and sits on a raised area in the center of Wolverhampton. The oldest part of the building is the crossing under the tower, which dates back to around 1200. The Chapel of Our Lady and St George (Lady Chapel) is also very old.

Much of the church was rebuilt and made bigger in the 1300s. Then, in the mid-1400s, the town's wool merchants paid for more changes. They added a clerestory (a row of windows above the main part of the church) to the nave. The upper part of the tower was rebuilt around 1475, reaching 120 feet high.

The chancel (the area around the altar) was rebuilt in 1682 after being damaged in the Civil War. It was rebuilt again in 1867 during a big restoration project.

Some unique features include a carved stone pulpit from the 1400s. It has a lion figure at the bottom of the steps, meant to protect the minister. The font (for baptisms) is from 1480 and has several carved stone figures. The wooden west gallery, built in 1610, was paid for by the Merchant Taylors' Company for boys from Wolverhampton Grammar School.

Near the south porch, there's a 14-foot-tall stone column. It was carved in the 800s with birds, animals, and plants. It might have been a preaching cross or a memorial. A copy of its carvings can be seen in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Bells of St Peter's

The bells at St Peter's are very special! They are the second oldest complete set of 12 bells in England and the third oldest in the world. All twelve bells were made in 1911 by Gillett & Johnston of Croydon.

The church had five bells in 1553. Over the years, more bells were added and recast. In 1911, all the bells were recast, and two new ones were added to make a full set of twelve. This was the first complete set of 12 bells made by Gillett & Johnston. They were rung for the first time as 12 for the coronation of King George V.

The bells are rung twice a week: for practice on Mondays and for the main Sunday service.

Music at St Peter's

The church has a large, three-manual Father Willis organ, built in 1860. It was fully restored in 2019.

St Peter's has a strong tradition of choral music. More than 40 children and young people are involved in the music program, along with adult singers. The boys' and girls' choirs often sing at cathedrals during the summer holidays. They have sung at famous places like York Minster, Canterbury Cathedral, and Salisbury Cathedral.

The church also works with schools to help children learn to sing. The current Acting Director of Music is Callum Alger.

St Peter's Church Today

Today, St Peter's practices a Catholic style of worship within the Church of England. This means they use special clothes (vestments) during services and sometimes use incense.

The church is open on weekdays and Saturdays. You can also visit before and after services on Sundays. There is a shop inside the church and a coffee lounge nearby.

St Peter's has close ties with St Peter's Collegiate School. While the school was founded next to the church in 1847, it is now located at Compton Park.

Rectors of St Peter's Collegiate Church

After the old college system was abolished in 1848, St Peter's became a parish church with a Rector.

- John Dakeyne, 1848

- John Iles, 1860

- John Jeffcock, 1877

- Alfred Penny, 1895

- Joseph Stockley, 1919

- Robert Hodson, 1929

- John Brierley, 1935

- Francis Cocks, 1965

- John Ginever, 1970

- John Hall-Matthews, 1990

- David Frith, 2003

- David Wright, 2009

Images for kids

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |