The Anarchy facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Anarchy |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

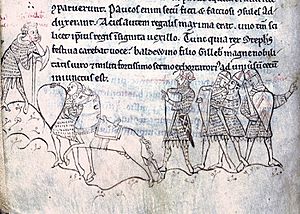

A drawing of the Battle of Lincoln; Stephen (fourth from the right) listens to Baldwin of Clare giving a speech. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Forces loyal to Stephen of Blois | Forces loyal to Empress Matilda & Henry Plantagenet | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Stephen of Blois Matilda of Boulogne |

Empress Matilda Robert of Gloucester Geoffrey Plantagenet Henry Plantagenet |

||||||

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Normandy. It lasted from 1138 to 1153. This conflict led to a lot of lawlessness and disorder across the country.

The war started because of a problem with who would be the next king. William Adelin, the only legal son of King Henry I, drowned in 1120. His ship, the White Ship, sank. King Henry I wanted his daughter, Empress Matilda, to be the next ruler. But he only partly convinced the nobles to support her.

When Henry died in 1135, his nephew Stephen of Blois quickly took the throne. He had help from his brother, Henry of Blois, who was the Bishop of Winchester. Stephen's early time as king saw many fights. He battled disloyal English nobles, rebellious Welsh leaders, and Scottish invaders. In 1139, Matilda invaded England. She had help from her half-brother, Robert of Gloucester.

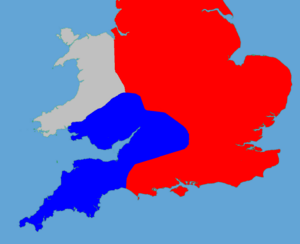

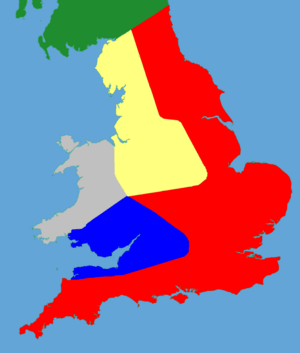

In the first years of the war, neither side gained a clear win. Empress Matilda controlled the south-west of England and parts of the Thames Valley. Stephen held the south-east. Many other areas were controlled by nobles who didn't support either side. Castles were strong, so fighting mostly involved sieges, raids, and small battles. Armies had knights and foot soldiers, often mercenaries.

In 1141, Stephen was captured after the Battle of Lincoln. This greatly weakened his power. When Empress Matilda tried to be crowned queen, angry crowds forced her out of London. Soon after, Robert of Gloucester was captured. The two sides then traded prisoners: Stephen for Robert. Stephen almost captured Matilda in 1142 during the siege of Oxford. But the Empress escaped from Oxford Castle by crossing the frozen River Thames.

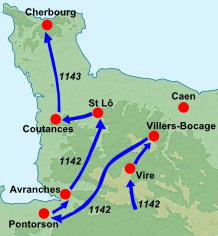

The war continued for many years. Empress Matilda's husband, Geoffrey V of Anjou, took control of Normandy for her in 1143. But in England, neither side could win. Rebellious nobles gained more power in northern England and East Anglia. Areas with heavy fighting suffered great damage. In 1148, Matilda went back to Normandy. Her young son, Henry FitzEmpress, took over the fighting in England.

In 1152, Stephen tried to get his oldest son, Eustace, recognized as the next king by the Catholic Church. But the Church refused. By the early 1150s, most nobles and the Church were tired of the war. They wanted a lasting peace.

Henry FitzEmpress invaded England again in 1153. But neither army wanted to fight much. After some small battles, the two armies faced each other at the siege of Wallingford. The Church helped arrange a truce, stopping a big battle. Stephen and Henry started talking about peace. During these talks, Eustace died from an illness. This removed Stephen's direct heir.

The Treaty of Wallingford was signed. It allowed Stephen to remain king. But it recognized Henry as his successor. Over the next year, Stephen began to regain control over the whole kingdom. He died of disease in 1154. Henry was crowned as Henry II. He was the first Angevin king of England. He then began a long period of rebuilding the country.

People at the time thought this conflict was very destructive. Chroniclers wrote that "Christ and his saints were asleep" during this time. Later historians called it "the Anarchy" because of the widespread chaos. However, modern historians question how accurate this term is for the whole country.

Why the War Started: The Succession Crisis

The White Ship Disaster

The Anarchy began because of a problem with who would rule England and Normandy next. In the 1000s and 1100s, many dukes and counts controlled north-west France. They often fought over land. In 1066, one of them, Duke William II of Normandy, invaded and conquered England. He then moved into Wales and northern England.

After William's death, his children fought over his lands. William's son Henry I took power. He later conquered Normandy from his older brother. Henry wanted his only legal son, 17-year-old William Adelin, to inherit all his lands.

But in 1120, the White Ship sank on its way to England. About 300 people died, including William Adelin. With William gone, who would inherit the English throne became unclear. Rules for who inherited power were not set in stone back then. In some places, the oldest son always inherited everything. In England and Normandy, lands were often divided.

The problem was made worse because the last few rulers of England and Normandy had not taken power peacefully.

With William Adelin dead, Henry had only one other legal child, Empress Matilda. But it was not clear if a woman could inherit the throne. Henry married again, but he didn't have another son. So, he decided Matilda would be his heir. Matilda had been married to a German emperor, which is why she was called "Empress." Her husband died in 1125. She then married Geoffrey V of Anjou in 1128. His lands bordered Normandy. Geoffrey was not popular with the Anglo-Norman nobles. People in Anjou were traditional enemies of the Normans.

King Henry tried to get support for Matilda. He made his court swear oaths in 1127, 1128, and 1131. These oaths said they would accept Matilda as his successor. Stephen was one of those who swore the oath. But relations between Henry, Matilda, and Geoffrey became difficult. Matilda and Geoffrey felt they didn't have enough support in England. They asked Henry to give Matilda control of royal castles in Normandy while he was still alive. This would make her position stronger after his death. Henry refused, fearing Geoffrey would try to take power early.

A new rebellion started in southern Normandy. Geoffrey and Matilda joined the rebels. In the middle of this, Henry suddenly got sick and died.

Who Became King?

After Henry's death, Stephen of Blois took the English throne, not Matilda. This led to the civil war. Stephen was the son of a powerful French count and Adela of Normandy, William the Conqueror's daughter. So, Stephen and Matilda were first cousins.

Stephen was a younger son with no lands of his own. He became a follower of King Henry. He traveled with Henry's court and fought in his campaigns. In return, he received lands. In 1125, he married Matilda of Boulogne. She was the only heir to the Count of Boulogne. This gave Stephen control of an important port and large estates in England. By 1135, Stephen was well-known. His younger brother, Henry of Blois, also became powerful. He was the Bishop of Winchester and the second richest man in England.

When King Henry I died, many possible heirs were not in a good position. Geoffrey and Matilda were in Anjou, fighting rebels. Many nobles had sworn to stay in Normandy until the king was buried. This stopped them from returning to England. Geoffrey and Matilda took some castles in southern Normandy but could not go further. Stephen's older brother, Theobald, was in Blois, further south.

Stephen was in Boulogne, a good location. When he heard of Henry's death, he quickly went to England. Some ports refused him entry at first. But Stephen reached his own estate near London by December 8. Over the next week, he began to take power.

The people of London traditionally claimed the right to choose the king. They declared Stephen the new monarch. They believed he would give the city new rights. Henry of Blois helped Stephen get the Church's support. Stephen went to Winchester. There, the royal treasury was given to him. On December 15, Henry made a deal. Stephen would give the Church many freedoms. In return, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Pope's representative supported him.

There was a problem: Stephen had sworn an oath to support Empress Matilda. But Henry argued that the late king was wrong to make that oath. He said Stephen was right to ignore it to prevent chaos. Henry also convinced a royal steward to swear that the king had changed his mind on his deathbed. The steward claimed the king had named Stephen as his heir. Stephen was crowned a week later on December 26.

Meanwhile, Norman nobles met to discuss making Theobald king. They thought Theobald, as the older grandson of William the Conqueror, had a stronger claim. Theobald met with them, but then heard Stephen was being crowned. Theobald agreed to be king, but his support quickly disappeared. The nobles didn't want to divide England and Normandy by opposing Stephen. Stephen later paid Theobald money. In return, Theobald stayed in Blois and supported his brother.

The Road to War

Stephen's Early Reign (1135–1138)

Stephen had to act quickly after his coronation. David I of Scotland, Matilda's uncle, invaded the north. He took Carlisle, Newcastle upon Tyne, and other strongholds. Northern England was disputed territory. Stephen marched north with an army and met David. They made a deal: David would return most land, except Carlisle. Stephen confirmed David's son's lands in England.

Stephen held his first royal court at Easter 1136. Many nobles and church officials attended. Stephen issued a new royal charter. He confirmed his promises to the Church. He also promised to change Henry's policies on royal forests. Stephen presented himself as Henry I's rightful successor. He confirmed the existing seven earldoms. The Easter court was very grand. Stephen spent a lot of money on it. He gave out land and favors.

Stephen's rule still needed the Pope's approval. His brother Henry of Blois helped get support from Theobald and the French king. Pope Innocent II confirmed Stephen as king later that year. Copies were sent around England to show Stephen's legitimacy.

Troubles continued across Stephen's kingdom. South Wales rebelled after Welsh victories in 1136. Owain Gwynedd and Gruffydd ap Rhys took much land. Stephen sent forces to calm the region, but they failed. By late 1137, Stephen seemed to give up on Wales. He focused on other problems. Stephen also put down two revolts in the south-west. One rebel, Baldwin de Redvers, went to Normandy. He became a strong critic of the king.

Geoffrey of Anjou attacked Normandy in early 1136. He raided and burned estates. Stephen could not go to Normandy himself. So, Waleran de Beaumont and Theobald defended the duchy. Stephen returned to Normandy in 1137. He met with the French king and Theobald. They agreed to an alliance against Angevin power. As part of this, the French king recognized Stephen's son Eustace as Duke of Normandy. Stephen was less successful in taking back the Argentan area. This area bordered Normandy and Anjou. Stephen formed an army, but his Flemish mercenaries and Norman barons fought each other. The Norman forces left, forcing Stephen to stop his campaign. Stephen agreed to another truce with Geoffrey. He promised to pay him money for peace along the borders.

Stephen's first years as king can be seen in different ways. He stabilized the Scottish border. He contained Geoffrey's attacks on Normandy. He had peace with the French king. He had good relations with the Church. He had broad support from his nobles. However, there were problems. David and Prince Henry controlled northern England. Stephen had given up on Wales. Fighting in Normandy had made the duchy unstable. More nobles felt Stephen had not given them enough land or titles. Stephen was also running out of money. Henry's treasury was empty by 1138. This was due to Stephen's lavish court and mercenary armies.

Early Battles (1138–1139)

Fighting broke out on several fronts in 1138. First, Robert of Gloucester rebelled against the king. This started the civil war in England. Robert was Henry I's illegitimate son and Matilda's half-brother. He was a very powerful noble. In 1138, Robert stopped supporting Stephen. He declared his support for Matilda. This caused a big rebellion in Kent and the south-west. Robert himself stayed in Normandy. Matilda had not been very active in claiming the throne since 1135. Robert largely started the war in 1138. In France, Geoffrey took advantage and invaded Normandy again. David of Scotland also invaded northern England again. He said he supported Empress Matilda. He pushed south into Yorkshire.

Stephen quickly responded to the revolts and invasions. He focused on England, not Normandy. His wife, Queen Matilda, went to Kent. She had ships and resources from Boulogne. Her task was to retake Dover, which Robert controlled. Some of Stephen's knights went north to fight the Scots. David's forces were defeated at the Battle of the Standard in August. Despite this win, David still held most of northern England. Stephen himself went west. He tried to regain control of Gloucestershire. He took Hereford and Shrewsbury. Then he went south to Bath. Bristol was too strong for him. Stephen just raided the area around it. The rebels seemed to expect Robert to help, but he stayed in Normandy. He tried to convince Empress Matilda to invade England herself. Dover finally surrendered to the queen's forces later that year.

Stephen's military campaign in England had gone well. The king used his military advantage to make peace with Scotland. Stephen's wife, Queen Matilda, negotiated a new agreement. It was called the Treaty of Durham. Northumbria and Cumbria were given to David and his son, Henry. In return, they swore loyalty and promised peace. The powerful Ranulf, Earl of Chester, was very unhappy. He felt he had rights to Carlisle and Cumberland. This problem would cause issues later in the war.

Getting Ready for War (1139)

By 1139, Robert and Matilda's invasion of England seemed very close. Geoffrey and Matilda had secured much of Normandy. They spent the start of the year gathering forces for a cross-Channel trip. Matilda also appealed to the Pope. She presented her legal claim to the English throne. The Pope did not change his earlier support for Stephen. But Matilda's case showed that Stephen's claim was disputed.

Meanwhile, Stephen prepared for the coming fight. He created more earldoms. Under Henry I, there were only a few symbolic earldoms. Stephen created many more. He gave them to men he trusted. These men were loyal and good military leaders. In vulnerable areas, he gave them new lands and more power. Stephen wanted to ensure his supporters' loyalty. He also wanted to improve his defenses. Stephen was greatly influenced by his main advisor, Waleran de Beaumont. Waleran and his family received most of these new earldoms. From 1138, Stephen gave them the earldoms of Worcester, Leicester, Hereford, Warwick and Pembroke. These, combined with Prince Henry's lands, created a large area to protect the kingdom.

Stephen also took steps to remove some bishops he saw as a threat. King Henry I's government was led by Roger, the Bishop of Salisbury. His nephews, Alexander and Nigel, were also bishops. Roger's son was the Lord Chancellor. These bishops owned a lot of land. They also built new castles and increased their armies. Stephen suspected they might join Empress Matilda. Roger and his family were also enemies of Waleran. In June 1139, Stephen held his court in Oxford. A fight broke out between Alan of Brittany and Roger's men. Stephen probably caused this incident. Stephen then demanded that Roger and the other bishops give up all their castles. He arrested the bishops, except Nigel, who hid in Devizes Castle. Nigel only surrendered after Stephen besieged the castle. The remaining castles were then given to the king. This removed any military threat from the bishops. But it may have hurt Stephen's relationship with the senior clergy, especially his brother Henry. Both sides were now ready for war.

How They Fought

Warfare Technology and Tactics

Warfare during the civil war was about slowly wearing down the enemy. Commanders raided enemy lands and took castles. This helped them control their opponents' territory. They aimed for slow, strategic wins. Big battles were sometimes fought, but they were very risky. Commanders usually tried to avoid them.

Norman warfare relied on rulers raising and spending a lot of money. The cost of war had risen a lot in the early 1100s. Having enough cash was very important for successful campaigns.

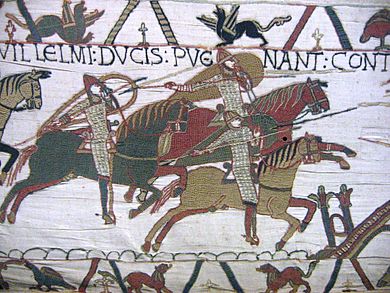

Stephen and Matilda's armies had small groups of knights. These knights formed the core of their military campaigns. Armies were similar to those of the previous century. They had mounted, armored knights and infantry. Many wore long mail shirts and helmets. Swords and lances were common. Crossbowmen were more numerous. Longbows were sometimes used. These forces were either feudal levies (local nobles' soldiers) or, more often, mercenaries. Mercenaries were expensive but more flexible and skilled.

Normans first built castles in the 900s and 1000s. They used them a lot after conquering England in 1066. Most castles were earth and timber motte-and-bailey or ringwork designs. These were easy to build with local workers and materials. They were strong and easy to defend. Nobles became good at placing castles along rivers and valleys. This helped them control people, trade, and regions. In the decades before the civil war, some new stone keeps were built. These were expensive and took a long time to build. The weapons used in the 1140s were not as powerful as later ones. This gave defenders a big advantage. So, commanders preferred long sieges to starve out defenders. Or they used mining to weaken walls, rather than direct attacks.

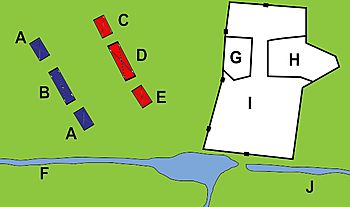

Both sides built new castles. Sometimes they created systems of strongholds. In the south-west, Matilda's supporters built castles to protect their land. These were usually motte-and-bailey designs. Stephen also built a new chain of castles. These protected his lands around Cambridge. Many of these castles were called "adulterine" or unauthorized. This was because no royal permission was given to build them during the chaos. People at the time were concerned about this. One writer suggested 1,115 such castles were built, but this was likely an exaggeration.

Another feature of the war was "counter-castles" or "siege castles." At least 17 such sites have been found. These were basic castles built during a siege. They were usually 180 to 270 meters away from the target. They could be used as platforms for siege weapons. Or they could be bases for controlling the region. Most siege castles were temporary and later destroyed.

Key Leaders

King Stephen was very rich, polite, modest, and well-liked. He was also seen as a man who could act firmly. As a military leader, he was skilled in personal combat. He was good at siege warfare. He could also move armies quickly over long distances. Rumors about his father's cowardice might have made Stephen take some risky military actions. Stephen relied heavily on his wife, Queen Matilda of Boulogne. She led negotiations and kept his cause alive when he was imprisoned in 1141.

Empress Matilda's side did not have a war leader like Stephen. Matilda had experience in government. She had led court cases and acted as a ruler in Italy. However, as a woman, Matilda could not lead forces into battle herself. Matilda was less popular with writers at the time than Stephen. She was often like her father, demanding obedience from her court. She sometimes made threats and seemed arrogant. This was seen as especially wrong because she was a woman. Matilda's husband, Geoffrey of Anjou, helped take Normandy. But he did not cross into England.

For most of the war, the Angevin armies were led by a few senior nobles. The most important was Robert of Gloucester, Matilda's half-brother. He was known as a statesman and for his military experience. Robert had tried to convince Theobald to take the throne in 1135. He did not attend Stephen's first court in 1136. Miles of Gloucester was another skilled military leader until his death in 1143. Brian Fitz Count was one of Matilda's most loyal followers. He was a marcher lord from Wales. Fitz Count was very committed to his oath to Matilda. He was crucial in defending the Thames area.

The Civil War Begins

First Phase of the War (1139–1140)

The Angevin invasion finally happened in August. Baldwin de Redvers crossed from Normandy to Wareham. He tried to capture a port for Empress Matilda's army. But Stephen's forces made him retreat. The next month, the Empress was invited to land at Arundel. On September 30, Robert of Gloucester and the Empress arrived in England with 140 knights. Matilda stayed at Arundel Castle. Robert marched north-west to Wallingford and Bristol. He hoped to gain support and join Miles of Gloucester. Miles then stopped supporting the king.

Stephen quickly moved south. He besieged Arundel and trapped Matilda inside. Stephen then agreed to a truce. His brother, Henry of Blois, suggested it. The details of the truce are not fully known. But Stephen released Matilda from the siege. He then allowed her and her knights to be escorted to the south-west. There, they rejoined Robert of Gloucester. Why Stephen released his rival is unclear. Some writers at the time said Henry argued it was best to attack Robert instead. Stephen may have seen Robert as his main enemy. Stephen also faced a military problem at Arundel. The castle was very strong. He might have worried about tying up his army while Robert was free in the west. Another idea is that Stephen released Matilda out of chivalry. Stephen was known for being generous. Women were not usually targeted in Anglo-Norman warfare.

Matilda now controlled a solid area. It stretched from Gloucester and Bristol into Devon and Cornwall. It also went west into Wales and east towards Oxford and Wallingford. This threatened London. She set up her court in Gloucester. Stephen began to reclaim the region. He first attacked Wallingford Castle, which controlled the Thames area. It was held by Brien FitzCount and was too well defended. Stephen left some forces to block the castle. He continued west into Wiltshire. He took the castles of South Cerney and Malmesbury. Meanwhile, Miles of Gloucester marched east. He attacked Stephen's forces at Wallingford. He also threatened to advance on London. Stephen had to stop his western campaign. He returned east to stabilize the situation and protect his capital.

At the start of 1140, Nigel, the Bishop of Ely, rebelled. Stephen had taken his castles the year before. Nigel hoped to seize East Anglia. He set up his base in the Isle of Ely, surrounded by marshland. Stephen responded quickly. He took an army into the marshes. He used boats tied together to make a path. This allowed him to surprise attack the isle. Nigel escaped, but his men and castle were captured. Order was temporarily restored in the east. Robert of Gloucester's men retook some land Stephen had taken in 1139. To negotiate a truce, Henry of Blois held a peace meeting at Bath. Robert represented the Empress. Queen Matilda and Archbishop Theobald represented the King. The meeting failed. Henry and the clergy insisted they should set the peace terms, which Stephen refused.

Ranulf of Chester was still angry about Stephen giving northern England to Prince Henry. Ranulf planned to ambush Henry. Stephen heard rumors of this plan. He escorted Henry north himself. But this made Ranulf even angrier. Ranulf had claimed rights to Lincoln Castle, held by Stephen. He seized the castle in a surprise attack. Stephen marched north to Lincoln. He agreed to a truce with Ranulf. This was probably to stop Ranulf from joining the Empress. Ranulf was allowed to keep the castle. Stephen returned to London. But he heard that Ranulf and his family were in Lincoln Castle with few guards. This was a chance for a surprise attack. Stephen broke his deal. He gathered his army and rushed north. But he was not fast enough. Ranulf escaped Lincoln and declared support for the Empress. Stephen had to besiege the castle.

Second Phase of the War (1141–1142)

Battle of Lincoln

Stephen and his army besieged Lincoln Castle in early 1141. Robert of Gloucester and Ranulf of Chester advanced on Stephen's position. They had a larger force. When Stephen heard this, he decided to fight. This led to the Battle of Lincoln on February 2, 1141. The king commanded the center of his army. Robert and Ranulf's forces had more cavalry. Stephen made many of his knights fight on foot. He joined them himself. Before the battle, Stephen's speech was given by Baldwin of Clare.

The battle went badly for Stephen. Robert and Ranulf's cavalry surrounded Stephen's center. Stephen found himself surrounded. Many of his supporters fled. But Stephen fought on. He used his sword, and then a borrowed battle axe. Finally, Robert's men captured him.

Robert took Stephen to Gloucester. The king met Empress Matilda there. Then he was moved to Bristol Castle. He was first held in good conditions, but later put in chains. The Empress began to prepare to be crowned queen. This needed the Church's agreement and a coronation at Westminster Abbey. Stephen's brother Henry called a council at Winchester. He was the Pope's representative. He had a secret deal with Matilda. He would get the Church's support if she gave him control over Church matters. Henry gave the royal treasury to the Empress. He also punished Stephen's supporters who refused to switch sides.

Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury did not want to declare Matilda queen so quickly. A group of clergy and nobles went to see Stephen in Bristol. They asked if they should break their oaths to him. Stephen agreed that, given the situation, he would release them from their oaths.

The clergy met again in Winchester. They declared the Empress "Lady of England and Normandy." This was a step before her coronation. Few major nobles attended. A group from London hesitated. Queen Matilda wrote to complain and demand Stephen's release. Empress Matilda then went to London for her coronation in June. But her position became risky. Forces loyal to Stephen and Queen Matilda were near the city. The citizens were afraid to welcome the Empress. On June 24, the city rose up against the Empress. Matilda and her followers barely escaped. They made a chaotic retreat to Oxford.

Meanwhile, Geoffrey of Anjou invaded Normandy again. He took all the duchy south of the River Seine. Stephen's brother Theobald did not help this time. He was busy with his own problems with France. The new French king, Louis VII, had better relations with Anjou. Geoffrey's success in Normandy and Stephen's weakness in England affected many nobles. They feared losing their lands. Many started to leave Stephen's side. His friend Waleran defected in mid-1141. He allied with the Angevins to secure his lands. Waleran's twin brother, Robert of Leicester, stopped fighting. Other supporters of the Empress got their old strongholds back. Some received new earldoms in western England. The royal control over making coins broke down. Local nobles and bishops started making their own coins.

Winchester and Oxford Sieges

Stephen's wife, Queen Matilda, was key to keeping his cause alive. She gathered Stephen's remaining supporters in the south-east. She advanced into London when the people rejected the Empress. Stephen's commander, William of Ypres, stayed with the queen. The queen seemed to gain real sympathy and support. Henry's alliance with the Empress was short-lived. They argued over political favors and Church policy. The bishop met Queen Matilda and switched his support to her.

The Empress's position changed after her defeat at the rout of Winchester. After leaving London, Robert of Gloucester and the Empress besieged Henry in his castle at Winchester. But Queen Matilda and William of Ypres then surrounded the Angevin forces. The Empress Matilda decided to escape with her close friends. The rest of her army delayed the royal forces. In the battle, the Empress's forces were defeated. Robert of Gloucester was captured during the retreat. Matilda herself escaped to her fortress at Devizes.

With both Stephen and Robert captured, talks were held for peace. But Queen Matilda would not compromise. Robert refused to switch sides to Stephen. Instead, in November, the two leaders were exchanged. Stephen returned to his queen. Robert returned to the Empress in Oxford. Henry held another church council. It reversed its earlier decision. It confirmed Stephen's right to rule. Stephen and Matilda had another coronation at Christmas 1141. In early 1142, Stephen fell ill. Rumors spread that he had died. He recovered and traveled north. He convinced Ranulf of Chester to switch sides again. Stephen then spent the summer attacking new Angevin castles. These included Cirencester, Bampton, and Wareham.

In mid-1142, Robert went back to Normandy. He helped Geoffrey fight Stephen's remaining supporters there. He returned to England later that year. Meanwhile, Matilda faced more pressure from Stephen's forces. She became surrounded at Oxford. Oxford was a secure town with walls and the River Isis. But Stephen led a sudden attack across the river. He swam part of the way. Once across, the king and his men broke into the town. They trapped the Empress in the castle. Oxford Castle was strong. Stephen had to settle for a long siege. He knew Matilda was trapped. Just before Christmas, the Empress sneaked out of the castle. She crossed the icy river on foot. She escaped past the royal army to safety at Wallingford. The castle garrison surrendered the next day. Matilda stayed with Fitz Count for a while. Then she set up her court again at Devizes.

Stalemate (1143–1146)

The war in England reached a standstill in the mid-1140s. Meanwhile, Geoffrey of Anjou took firm control of Normandy. He was recognized as duke after taking Rouen in 1144. 1143 started badly for Stephen. Robert of Gloucester besieged him at Wilton Castle. Stephen tried to escape, leading to the Battle of Wilton. Again, the Angevin cavalry was too strong. It looked like Stephen might be captured again. But William Martel, Stephen's steward, fought hard. This allowed Stephen to escape. Stephen valued William's loyalty. He agreed to give up Sherborne Castle for William's safe release. This was rare for Stephen.

In late 1143, Stephen faced a new threat in the east. Geoffrey de Mandeville, the Earl of Essex, rebelled. Stephen had disliked him for years. Stephen provoked the conflict by arresting Geoffrey at court. Stephen threatened to execute Geoffrey. He demanded that Geoffrey hand over his castles. These included the Tower of London, Saffron Walden, and Pleshey. These were important forts near London. Geoffrey gave in. But once free, he went north-east into the Fens. From the Isle of Ely, he began a campaign against Cambridge. He planned to move south towards London. Stephen had many other problems. He lacked the resources to track Geoffrey in the Fens. He built a line of castles between Ely and London.

For a time, the situation got worse. Ranulf of Chester rebelled again in mid-1144. He divided Stephen's lands between himself and Prince Henry. In the west, Robert of Gloucester continued to raid royalist areas. Wallingford Castle remained a strong Angevin base. It was too close to London. Meanwhile, Geoffrey of Anjou finished securing southern Normandy. In January 1144, he entered Rouen, the capital. The French king recognized him as Duke of Normandy. By this point, Stephen relied more on his close royal household. He lacked support from major nobles. After 1141, Stephen used his network of earls less.

After 1143, the war continued, but slightly better for Stephen. Miles of Gloucester, a skilled Angevin commander, died while hunting. This eased some pressure in the west. Geoffrey de Mandeville's rebellion continued until September 1144. He died during an attack on Burwell. The war in the west improved in 1145. The king recaptured Faringdon Castle in Oxfordshire. In the north, Stephen made a new agreement with Ranulf of Chester. But in 1146, he used the same trick he played on Geoffrey de Mandeville. He invited Ranulf to court, arrested him, and threatened to execute him. He demanded Ranulf hand over castles like Lincoln and Coventry. Like Geoffrey, Ranulf rebelled once released. But it was a stalemate. Stephen had few forces in the north for a new campaign. Ranulf lacked castles to attack Stephen. By this point, Stephen's practice of arresting nobles at court had made him distrusted.

Final Stages of the War (1147–1152)

The nature of the conflict in England slowly changed. By the late 1140s, the civil war was mostly over. There were only occasional outbreaks of fighting. In 1147, Robert of Gloucester died peacefully. The next year, Empress Matilda settled a dispute with the Church. She returned to Normandy, which helped slow down the war. The Second Crusade was announced. Many Angevin supporters joined it, leaving the region for years. Many nobles made their own peace agreements. They wanted to secure their lands and war gains.

Geoffrey and Matilda's son, the future King Henry II, launched a small invasion in 1147. But the expedition failed. Henry lacked money to pay his men. Surprisingly, Stephen paid their costs. This allowed Henry to return home safely. Stephen's reasons for this are unclear. It might have been his general courtesy to family. Or he might have been thinking about ending the war peacefully.

Many powerful nobles made their own truces. They signed treaties promising to stop fighting each other. They limited new castle building. They also agreed on army sizes. These treaties usually said nobles might still have to fight if their rulers ordered it. By the 1150s, a network of treaties had formed. This reduced local fighting, but didn't stop it completely.

Matilda stayed in Normandy for the rest of the war. She focused on stabilizing the duchy. She also promoted her son's claim to the English throne. Young Henry FitzEmpress returned to England in 1149. This time, he planned to form a northern alliance with Ranulf of Chester. Henry and Ranulf agreed to attack York. Stephen quickly marched north to York. The planned attack fell apart. Henry returned to Normandy. His father declared him Duke. Though young, Henry was gaining a reputation as a strong leader. His power grew when he married Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152. Eleanor was the Duchess of Aquitaine and recently divorced from the French king. This marriage made Henry the future ruler of a huge area across France.

In the final years of the war, Stephen also focused on his family and who would inherit the throne. Stephen had given his oldest son Eustace the County of Boulogne in 1147. But it was unclear if Eustace would inherit England. Stephen wanted Eustace crowned while he was still alive. This was common in France. But it was not normal in England. The Pope had banned any change to this practice. The only person who could crown Eustace was Archbishop Theobald. The Archbishop refused to crown Eustace without the current Pope's agreement. The matter was stuck. Stephen's situation worsened due to arguments with Church members.

Stephen tried again to have Eustace crowned at Easter 1152. He gathered his nobles to swear loyalty to Eustace. Then he insisted that Theobald and his bishops crown him king. When Theobald refused again, Stephen and Eustace imprisoned them. They refused to release them unless they agreed. Theobald escaped into temporary exile. This marked a low point in Stephen's relationship with the Church.

End of the War

Peace Talks (1153–1154)

Henry FitzEmpress returned to England in early 1153 with a small army. He was supported by Ranulf of Chester and Hugh Bigod. Henry's forces besieged Stephen's castle at Malmesbury. The king marched west to relieve it. Stephen tried to force Henry's smaller army to fight a big battle. But he failed. Because of the winter weather, Stephen agreed to a truce. He returned to London. Henry traveled north through the Midlands. There, the powerful Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester, supported Henry. Henry and his allies now controlled the south-west, the Midlands, and much of northern England.

A group of senior English clergy met with Henry before Easter. They supported Stephen as king, but wanted peace. Henry promised to avoid English cathedrals. He also said he would not expect bishops to attend his court.

Stephen increased the long siege of Wallingford Castle. This was a major Angevin stronghold. Its fall seemed close. Henry marched south to help. He arrived with a small army. He then besieged Stephen's forces. Stephen gathered a large force and marched from Oxford. The two sides faced each other across the River Thames at Wallingford in July. By this point, nobles on both sides wanted to avoid a big battle. So, Church members helped arrange a truce. This annoyed both Stephen and Henry.

After Wallingford, Stephen and Henry talked privately about ending the war. Stephen's son Eustace was furious about the peaceful outcome. He left his father and returned home. He wanted to raise more money for a new campaign. But he fell ill and died the next month. Eustace's death removed a clear heir to the throne. This made it easier for those seeking peace. It's possible Stephen was already thinking of passing over Eustace.

Fighting continued after Wallingford, but half-heartedly. Stephen lost Oxford and Stamford to Henry. This happened while the king was fighting Hugh Bigod in eastern England. But Nottingham Castle survived an Angevin attack. Meanwhile, Stephen's brother Henry of Blois and Archbishop Theobald worked together. They pushed Stephen to accept a deal. Stephen and Henry FitzEmpress's armies met again at Winchester. The two leaders would confirm the peace terms in November.

Stephen announced the Treaty of Winchester in Winchester Cathedral. He recognized Henry FitzEmpress as his adopted son and successor. In return, Henry swore loyalty to him. Stephen promised to listen to Henry's advice. But he kept all his royal powers. Stephen's remaining son, William, would swear loyalty to Henry. He would give up his claim to the throne. In exchange, his lands would be safe. Key royal castles would be held for Henry by guarantors. Stephen would have access to Henry's castles. Foreign mercenaries would be sent home. Stephen and Henry sealed the treaty with a kiss of peace in the cathedral.

Transition and Rebuilding (1154–1165)

Stephen's decision to recognize Henry as his heir was not necessarily the final solution. Stephen might have lived many more years. Henry's position on the continent was also not fully secure. Stephen's son William was young. He was not ready to challenge Henry in 1153. But the situation could have changed later. There were rumors in 1154 that William planned to kill Henry. Historians describe the treaty as a "precarious peace." This means the situation in late 1153 was still uncertain.

However, Stephen became very active in early 1154. He traveled widely across the kingdom. He started issuing royal orders for the south-west again. He went to York and held a major court. He wanted to show northern nobles that royal authority was back. In 1154, Stephen traveled to Dover. He met the Count of Flanders. Some historians believe the king was already ill. He might have been preparing to settle his family affairs. Stephen fell ill with a stomach problem and died on October 25.

Henry did not rush back to England. He landed on December 8, 1154. Henry quickly took oaths of loyalty from some nobles. He was then crowned with Eleanor at Westminster. The royal court met in April 1155. Nobles swore loyalty to the king and his sons. Henry presented himself as the rightful heir to Henry I. He began rebuilding the kingdom. Stephen had tried to continue Henry I's government during the war. But the new government described Stephen's 19-year reign as chaotic. They said all problems came from Stephen taking the throne. Henry also showed he would listen to advice, unlike his mother. Various actions were taken immediately. Henry spent much of his early reign in France. So, much work was done from afar.

England had suffered greatly during the war. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle wrote that "there was nothing but disturbance and wickedness and robbery." In many parts of the country, fighting and raiding caused serious damage. The royal coinage system was broken. Stephen, the Empress, and local lords all made their own coins. Royal forest law had collapsed. However, some areas were barely touched by the conflict. Stephen's lands in the south-east and Angevin areas around Gloucester were mostly fine. David I ruled his northern territories well. The king's income from his lands dropped greatly after 1141. Royal control over making new coins was limited outside the south-east. Stephen was often based in the south-east. So, Westminster became the center of government, not Winchester.

Among Henry's first actions was to send away foreign mercenaries. He also continued to demolish unauthorized castles. One writer said 375 were destroyed. But recent studies suggest fewer were destroyed. Many might have just been abandoned. Henry also focused on restoring royal finances. He brought back Henry I's financial methods. By the 1160s, financial recovery was mostly complete.

The post-war period also saw activity around England's borders. The king of Scotland and Welsh rulers had taken advantage of the civil war. They seized disputed lands. Henry set about taking them back. In 1157, Henry pressured Malcolm IV of Scotland. Malcolm returned lands in northern England he had taken. Henry quickly began to strengthen the northern border. Restoring English control in Wales was harder. Henry had to fight two campaigns in 1157 and 1158. The Welsh princes finally submitted to his rule. They agreed to the pre-civil war land divisions.

Legacy of the Anarchy

How Historians See It

Much of what we know about the Anarchy comes from writers who lived at the time. These accounts give a rich picture of the period. However, all these writers had their own biases. Several key accounts were written in south-west England. These include the Gesta Stephani and William of Malmesbury's Historia Novella. In Normandy, Orderic Vitalis wrote his Ecclesiastical History. Robert of Torigni wrote a later history. Henry of Huntingdon, from eastern England, wrote the Historia Anglorum. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was less important by this time. But the version from Peterborough Abbey is famous for its description of the Anarchy. It said, "men said openly that Christ and his saints were asleep." Most of these writings show some bias for or against the main figures in the conflict.

The term "the Anarchy" to describe the civil war has been much discussed. The phrase itself came from the late 1800s. Many historians then saw English history as a steady path of political growth. William Stubbs analyzed the political side of the period. He saw a clear break in the English constitution in the 1140s. His student John Round then created the term "the Anarchy." Later historians criticized this term. Financial records and other documents suggested that the breakdown of law and order was more limited. It was not as widespread as the writers at the time suggested. More recent work in the 1990s looked at Henry's rebuilding efforts. It suggested more continuity with Stephen's wartime government. The label "the Anarchy" is still used by modern historians. But it is rarely used without some explanation.

The Anarchy in Stories

The civil war years have sometimes been used in historical fiction. Stephen, Matilda, and their supporters appear in Ellis Peters' detective series. These stories are set between 1137 and 1145. Peters shows the civil war as a local event. It focuses on Shrewsbury and its area. Peters portrays Stephen as a tolerant and reasonable ruler. This is despite his execution of Shrewsbury defenders in 1138. In contrast, Ken Follett's novel The Pillars of the Earth shows Stephen as an incapable ruler. Follett uses the White Ship sinking to set the scene. But in many ways, Follett uses the war as a background for a story about modern people and problems. This is also true in the TV mini-series based on the book.

|

See also

In Spanish: Anarquía inglesa para niños

In Spanish: Anarquía inglesa para niños

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |