Empress Matilda facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Matilda |

|

|---|---|

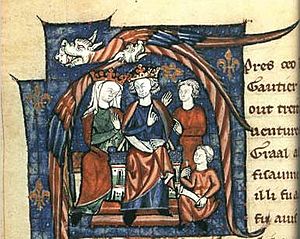

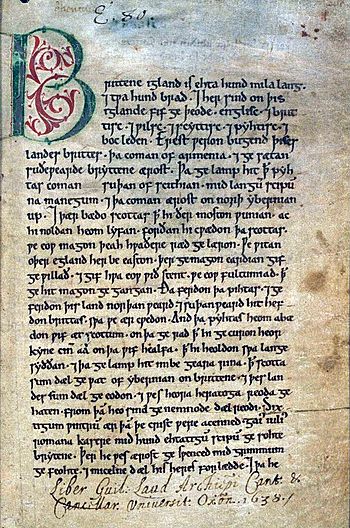

A picture of Empress Matilda from an old book.

|

|

| Holy Roman Empress Queen of the Romans |

|

| Tenure | 7 January 1114 – 23 May 1125 |

| Lady of the English (disputed) | |

| Reign | 8 April 1141 – 1148 |

| Predecessor | Stephen (as King of England) |

| Successor | Stephen (as King of England) |

| Born | c. 7 February 1102 Possibly Winchester or Sutton Courtenay, England |

| Died | 10 September 1167 (aged 65) Rouen, France |

| Burial | Rouen Cathedral, France |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue | |

| House | Normandy |

| Father | Henry I of England |

| Mother | Matilda of Scotland |

Empress Matilda (born around 7 February 1102, died 10 September 1167), also known as Empress Maude, was a very important person in English history. She was the daughter of King Henry I of England. She claimed the English throne during a civil war called the Anarchy.

When Matilda was a child, she moved to Germany to marry the future Holy Roman Emperor Henry V. She even traveled to Italy with him and was crowned in St Peter's Basilica. She also helped rule Italy for a while. Matilda and Henry V did not have any children. When he died in 1125, another ruler, Lothair of Supplinburg, became the new emperor.

Matilda's only full brother, William Adelin, died in a terrible ship accident in 1120. This meant King Henry I had no other sons to take his place. After her husband Henry V died, Matilda returned to Normandy. Her father arranged for her to marry Geoffrey of Anjou. This marriage was meant to create an alliance and protect his lands. King Henry I named Matilda as his heir and made his nobles promise to support her. However, many nobles did not like this idea.

When King Henry I died in 1135, Matilda and Geoffrey faced strong opposition. Instead of Matilda, her cousin Stephen of Blois took the throne. Stephen had the support of the English Church. He tried to make his rule strong, but he faced many threats.

In 1139, Matilda came to England to fight for the throne. She was supported by her half-brother Robert of Gloucester and her uncle King David I of Scotland. Her husband, Geoffrey, focused on taking control of Normandy. Matilda's forces captured Stephen at the Battle of Lincoln in 1141. However, Matilda's attempt to be crowned queen in Westminster failed because the people of London were against her. Because of this, Matilda was never officially crowned Queen of England. Instead, she was called "Lady of the English."

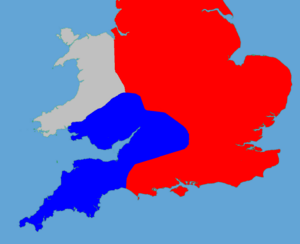

Later in 1141, Robert of Gloucester was captured. Matilda agreed to exchange him for Stephen. That winter, Matilda was trapped in Oxford Castle by Stephen's army. To escape, she had to sneak out at night across the frozen River Isis. She reportedly wore white clothes to blend in with the snow. The war became a stalemate. Matilda controlled much of the southwest of England, while Stephen controlled the southeast and the middle parts. Many other areas were controlled by local nobles.

Matilda returned to Normandy in 1148, which her husband now controlled. She left her oldest son to continue the fight in England. He eventually became King Henry II in 1154, creating the Angevin Empire. Matilda lived near Rouen and spent the rest of her life helping to govern Normandy. She often gave political advice to her son. She also worked closely with the Church, helping to start new monasteries. She was known for being very religious. Matilda died in 1167 and was buried at Bec Abbey.

Contents

Empress Matilda's Early Life

Matilda was born to Henry I, who was King of England and Duke of Normandy, and his first wife, Matilda of Scotland. She was likely born around February 7, 1102, possibly in Sutton Courtenay, England. Her father, Henry, was the youngest son of William the Conqueror. William had invaded England in 1066, creating a large kingdom that included parts of Wales.

This invasion created a group of powerful nobles called the Anglo-Normans. Many of them owned land on both sides of the English Channel. These nobles often had strong connections to the kingdom of France. At that time, France was a collection of smaller areas with a king who had little control. Matilda's mother was the daughter of King Malcolm III of Scotland. She was also related to the old English royal family, including Alfred the Great. By marrying Matilda's mother, King Henry I made his rule seem more legitimate.

Matilda had one younger, legitimate brother, William Adelin. Her father also had about 22 other children with different women. We don't know much about Matilda's very early life. She probably stayed with her mother and learned to read. She was also taught about religious morals. Important people at her mother's court included her uncle David, who later became King of Scotland. Her half-brother Robert of Gloucester and her cousin Stephen of Blois were also there.

In 1108, King Henry left Matilda and William with Anselm, the archbishop of Canterbury, while he went to Normandy. Anselm was a favorite church leader of Matilda's mother. There are no detailed descriptions of what Matilda looked like. People at the time said she was very beautiful, but this might have just been a common way for writers to describe important people.

Life in the Holy Roman Empire

Marriage and Coronation in Germany

In late 1108 or early 1109, King Henry V of Germany sent messengers to Normandy. He wanted to propose that Matilda marry him. He also wrote to her mother about it. This marriage was a good idea for the English king. His daughter would marry into one of the most important royal families in Europe. This would make his own family, which was quite new, seem more important. It would also give him an ally against France. In return, Henry V would receive a large sum of money, 10,000 marks. He needed this money to pay for a trip to Rome to be crowned Holy Roman emperor.

The final details of the marriage were agreed upon in Westminster in June 1109. Because her status was changing, Matilda attended a royal meeting for the first time that October. She left England in February 1110 to travel to Germany.

Matilda and Henry met in Liège. Then they traveled to Utrecht, where they officially got engaged on April 10. On July 25, Matilda was crowned German queen in a ceremony in Mainz. There was a big age difference between them: Matilda was only eight years old, while Henry was 24. After the engagement, Matilda was placed in the care of Bruno, the archbishop of Trier. He was in charge of teaching her about German culture, manners, and government.

In January 1114, Matilda was ready to marry Henry. Their wedding took place in the city of Worms with huge celebrations. Matilda then began her public life in Germany, with her own household of servants and staff.

Soon after the marriage, political problems started across the Empire. Henry arrested his chancellor, Archbishop Adalbert of Mainz, and other German princes. This led to rebellions and opposition from the Church. The Church was very important in running the Empire. This also led to the Pope, Pope Paschal II, officially removing the Emperor from the Church.

Henry and Matilda marched over the Alps into Italy in early 1116. They wanted to solve the problems with the Pope. Matilda was now fully involved in the imperial government. She approved royal grants, met with people asking for favors, and took part in important ceremonies. They spent the rest of the year taking control of northern Italy. In early 1117, they marched towards Rome itself.

Pope Paschal fled when Henry and Matilda arrived with their army. In his absence, a papal representative named Maurice Bourdin crowned them at St Peter's Basilica. This likely happened around Easter and definitely again at Pentecost. Matilda used these ceremonies to claim the title of Empress of the Holy Roman Empire. The Empire was ruled by kings who were chosen by the main nobles. These kings hoped to be crowned emperors by the Pope, but it wasn't guaranteed. Henry V had forced Pope Paschal II to crown him in 1111. Matilda's own status was less clear. Because of her marriage, she was clearly the rightful Queen of the Romans. She used this title on her seal and documents. But it was uncertain if she had a true claim to the title of Empress.

Both Bourdin's position and the ceremonies themselves were confusing. The ceremonies were not strictly imperial coronations. They were more like formal "crown-wearing" events. These were times when rulers would wear their crowns in court. Bourdin had also been removed from the Church when he performed the second ceremony. He was later removed from his position and imprisoned for life by Pope Callixtus II. Despite this, Matilda insisted that she had been officially crowned Empress in Rome. Her use of the title became widely accepted. Matilda used the title Empress from 1117 until she died. Everyone, from government officials to writers, called her Empress without question.

Matilda as a Widow

In 1118, Henry went back north into Germany to stop new rebellions. He left Matilda in charge of governing Italy. We don't have many records of her rule during these two years. However, she probably gained a lot of practical experience in how to govern. In 1119, she returned north to meet Henry in Lotharingia. Her husband was busy trying to make peace with the Pope, who had removed him from the Church.

In 1122, Henry and probably Matilda were at the Council of Worms. This meeting settled a long-running argument with the Church. Henry gave up his right to appoint bishops. Matilda tried to visit her father in England that year. But the journey was blocked by Count Charles I of Flanders, whose land she needed to cross. Historian Marjorie Chibnall believes Matilda wanted to discuss who would inherit the English crown on this trip.

Matilda and Henry did not have children. People at the time did not think either of them was unable to have children. Writers blamed their situation on the Emperor and his sins against the Church. In early 1122, the couple traveled down the Rhine river together. Henry continued to try and stop political unrest. But by then, he was suffering from cancer. He died on May 23, 1125, in Utrecht. He left Matilda under the protection of their nephew Frederick, who would inherit his lands. Matilda also had the imperial symbols of power. It's not clear what instructions he gave her about the future of the Empire. The Empire faced another election for a new leader. Archbishop Adalbert then convinced Matilda to give him the imperial symbols. He led the election process that chose Lothair of Supplinburg, a former enemy of Henry, as the new king.

Matilda was now 23 years old. She had limited choices for her future. Since she had no children, she could not act as a ruler for the Empire. This left her with two choices: become a nun or remarry. Some German princes offered to marry her. But she chose to return to Normandy. She did not seem to expect to go back to Germany. She gave up her lands in the Empire. She left with her personal jewels, her own imperial symbols, two of Henry's crowns, and a valuable religious item called the Hand of St James the Apostle.

The Fight for the Throne

The White Ship Disaster

In 1120, the political situation in England changed completely after the White Ship disaster. About 300 people, including Matilda's brother William Adelin and many other important nobles, boarded the White Ship one night. They were traveling from Barfleur in Normandy to England. The ship sank just outside the harbor. This might have been because it was too crowded or because the captain and crew drank too much. All but two of the passengers died. William Adelin was one of them.

With William dead, who would be the next king of England was now uncertain. Rules for who inherited the throne were not clear in western Europe at that time. In some parts of France, the oldest son would inherit titles. It was also common for the king of France to crown his successor while he was still alive. This made the line of succession clear. But this was not the case in England. The best a noble could do was to name a group of possible heirs. They would then fight over who would inherit after his death. The problem was made even more complicated by the unstable successions in England over the past 60 years. William the Conqueror had invaded England. His sons William Rufus and Robert Curthose had fought a war over their inheritance. Henry had only gained control of Normandy by force. There had been no peaceful, undisputed successions.

At first, King Henry hoped to have another son. William and Matilda's mother had died in 1118. So Henry married a new wife, Adeliza of Louvain. But Henry and Adeliza did not have any children. The future of the royal family seemed at risk. Henry may have started looking at his nephews for a possible heir. He might have thought about his sister Adela's son Stephen of Blois. To prepare for this, he arranged a good marriage for Stephen to Matilda's wealthy cousin, Countess Matilda I of Boulogne. Count Theobald IV of Blois, another nephew and close friend, also might have felt he was favored by Henry. William Clito, the only son of Robert Curthose, was King Louis VI of France's preferred choice. But William was openly fighting against Henry and was therefore not suitable. Henry might also have thought about his own illegitimate son, Robert of Gloucester. But English tradition would not have favored this. Henry's plans changed when Empress Matilda's husband, Emperor Henry, died in 1125.

Matilda Marries Geoffrey of Anjou

Matilda returned to Normandy in 1125. She spent about a year at the royal court. Her father was still hoping that his second marriage would result in a son. If not, Matilda was Henry's preferred choice. He declared that she would be his rightful successor if he had no other legitimate son. The Anglo-Norman nobles gathered in Westminster at Christmas 1126. In January, they swore an oath to recognize Matilda and any future legitimate children she might have.

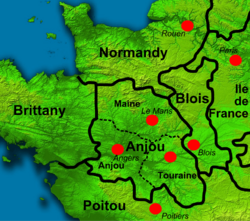

Henry began looking for a new husband for Matilda in early 1127. He received several offers from princes in the Empire. But he preferred to use Matilda's marriage to protect the southern borders of Normandy. He wanted to marry her to Geoffrey, the oldest son of Count Fulk V of Anjou. Henry's control of Normandy had faced many challenges since he conquered it in 1106. The newest threat came from his nephew William Clito, the new count of Flanders. William had the support of the French king. It was very important to Henry that he did not face a threat from the south as well as the east of Normandy. William Adelin had married Fulk's daughter Matilda. This would have created an alliance between Henry and Anjou. But the White Ship disaster ended this. Henry and Fulk argued over the marriage money. This had encouraged Fulk to support William Clito instead. Henry's solution was now to arrange the marriage of Matilda to Geoffrey, bringing back the old alliance.

Matilda did not seem happy about marrying Geoffrey of Anjou. She felt that marrying the son of a count lowered her imperial status. She was probably also unhappy about marrying someone so much younger than her. Matilda was 25, and Geoffrey was 13. Hildebert, the Archbishop of Tours, eventually convinced her to agree to the engagement. Matilda finally agreed. She traveled to Rouen in May 1127 with Robert of Gloucester and Brian Fitz Count. There, she was formally engaged to Geoffrey. Over the next year, Fulk decided to go to Jerusalem, where he hoped to become king. He left his lands to Geoffrey. Henry knighted his future son-in-law. Matilda and Geoffrey were married a week later on June 17, 1128, in Le Mans. Fulk finally left Anjou for Jerusalem in 1129, declaring Geoffrey the count of Anjou and Maine.

Family Disputes and the Road to War

The marriage was difficult because Matilda and Geoffrey did not like each other much. There was also a dispute over Matilda's dowry (money or property brought by a bride). Henry granted her several castles in Normandy. But it was not clear when they would actually take control of them. It is also unknown if Henry intended Geoffrey to have any future claim on England or Normandy. He was probably keeping Geoffrey's status deliberately unclear. Soon after the marriage, Matilda left Geoffrey and returned to Normandy. Henry seemed to blame Geoffrey for the separation. But the couple finally made up in 1131. Henry called Matilda from Normandy, and she arrived in England that August. It was decided that Matilda would return to Geoffrey at a meeting of the King's great council in September. The council also gave another group oath to recognize her as Henry's heir.

Matilda gave birth to her first son, the future Henry II, in March 1133 in Le Mans. Henry I was very happy and came to see her in Rouen. In June 1134, their second son Geoffrey was born in Rouen. But the birth was very difficult, and Matilda seemed close to death. She made plans for her will and argued with her father about where she should be buried. Matilda preferred Bec Abbey, but Henry wanted her to be buried at Rouen Cathedral. Matilda recovered, and Henry was overjoyed by the birth of his second grandson. He possibly insisted on another round of oaths from his nobles.

From then on, relations between Matilda and Henry became more strained. Matilda and Geoffrey suspected that they did not have real support in England for their claim to the throne. In 1135, they suggested that the King should give the royal castles in Normandy to Matilda. They also wanted him to insist that the Norman nobles immediately promise loyalty to her. This would have given the couple a much stronger position after Henry's death. But the King angrily refused. He was probably worried that Geoffrey would try to take power in Normandy while he was still alive. A new rebellion broke out in southern Normandy. Geoffrey and Matilda joined the rebels militarily.

In the middle of this conflict, Henry suddenly became ill and died near Lyons-la-Forêt. It is uncertain what, if anything, Henry said about who should succeed him before his death. Accounts from writers at the time were influenced by later events. Sources that favored Matilda suggested that Henry had confirmed his intention to give all his lands to his daughter. However, hostile writers argued that Henry had changed his mind and apologized for forcing the nobles to swear loyalty to her.

Stephen Takes the Throne

When news of Henry I's death spread, Matilda and Geoffrey were in Anjou. They were supporting rebels against the royal army. This army included some of Matilda's supporters, like Robert of Gloucester. Many of these nobles had sworn to stay in Normandy until the late king was properly buried. This stopped them from returning to England. However, Geoffrey and Matilda used the chance to march into southern Normandy. They seized several important castles around Argentan that were part of Matilda's disputed dowry. They then stopped, unable to go further. They pillaged the countryside and faced more resistance from the Norman nobles and a rebellion in Anjou itself. Matilda was also pregnant with her third son, William. Historians disagree on how much this affected her military plans.

Meanwhile, news of Henry's death reached Stephen of Blois. He was conveniently located in Boulogne. He left for England with his soldiers. Robert of Gloucester had soldiers guarding the ports of Dover and Canterbury. Some stories say they refused Stephen entry when he first arrived. However, Stephen reached the edge of London by December 8. Over the next week, he began to take power in England. The people in London declared Stephen the new king. They believed he would give the city new rights and benefits. His brother, Henry of Blois, the bishop of Winchester, brought the support of the Church to Stephen. Stephen had sworn to support Matilda in 1127. But Henry argued that the late King had been wrong to make his court take the oath. He also suggested that the King had changed his mind just before he died. Stephen's coronation was held at Westminster Abbey on December 22.

After hearing that Stephen was gaining support in England, the Norman nobles gathered at Le Neubourg. They discussed declaring Stephen's elder brother Theobald king. The Normans argued that Theobald, as the oldest grandson of William the Conqueror, had the strongest claim to the kingdom and the Duchy. They certainly preferred him over Matilda. Their discussions were interrupted by sudden news from England that Stephen's coronation would happen the next day. Theobald's support quickly disappeared. The nobles were not prepared to divide England and Normandy by opposing Stephen.

Matilda gave birth to her third son, William, on July 22, 1136, in Argentan. She then operated from the border region for the next three years. She set up her knights on estates around the area. Matilda may have asked Ulger, the bishop of Angers, to gain support for her claim with Pope Innocent II in Rome. But if she did, Ulger was not successful. Geoffrey invaded Normandy in early 1136. After a temporary peace, he invaded again later that year. He raided and burned estates rather than trying to hold the territory. Stephen returned to the Duchy in 1137. There, he met with Louis VI and Theobald to agree to an informal alliance against Geoffrey and Matilda. This was to counter the growing Angevin power in the region. Stephen formed an army to retake Matilda's Argentan castles. But disagreements between his Flemish mercenary soldiers and the local Norman nobles resulted in a battle between the two parts of his army. The Norman forces then left the King, forcing Stephen to give up his campaign. Stephen agreed to another truce with Geoffrey. He promised to pay him 2,000 marks a year for peace along the Norman borders.

In England, Stephen's reign started well. He held lavish gatherings of the royal court. He gave out land and favors to his supporters. Stephen received the support of Pope Innocent II, partly thanks to Louis VI and Theobald. But problems quickly began to appear. Matilda's uncle, David I of Scotland, invaded northern England when he heard of Henry's death. He took Carlisle, Newcastle, and other important strongholds. Stephen quickly marched north with an army and met David at Durham. They agreed to a temporary compromise. South Wales rebelled, and by 1137 Stephen had to give up trying to stop the revolt. Stephen put down two revolts in the southwest led by Baldwin de Redvers and Robert of Bampton. Baldwin was released after his capture and traveled to Normandy. There, he became a strong critic of the King.

The Revolt Begins

Matilda's half-brother, Robert of Gloucester, was one of the most powerful Anglo-Norman nobles. He controlled lands in Normandy and the Earldom of Gloucester. In 1138, he rebelled against Stephen. This started the civil war in England. Robert broke his promise of loyalty to the King and declared his support for Matilda. This caused a major rebellion in Kent and across the southwest of England. Robert himself stayed in Normandy. Matilda had not been very active in pushing her claim to the throne since 1135. In many ways, it was Robert who started the war in 1138. In France, Geoffrey took advantage of the situation by invading Normandy again. David of Scotland also invaded northern England once more. He announced that he was supporting Matilda's claim to the throne, pushing south into Yorkshire.

Stephen responded quickly to the revolts and invasions. He paid most attention to England rather than Normandy. His wife, Queen Matilda, was sent to Kent with ships and resources from Boulogne. Her task was to retake the important port of Dover, which was under Robert's control. A small number of Stephen's knights were sent north to help fight the Scots. David's forces were defeated later that year at the Battle of the Standard. Despite this victory, David still controlled most of the north. Stephen himself went west to try and regain control of Gloucestershire. He first went north into the Welsh Marches, taking Hereford and Shrewsbury. Then he headed south to Bath. The town of Bristol itself was too strong for him. Stephen was content with raiding and pillaging the surrounding area. The rebels seemed to expect Robert to intervene with support. But he remained in Normandy throughout the year, trying to persuade Empress Matilda to invade England herself. Dover finally surrendered to the Queen's forces later in the year.

By 1139, an invasion of England by Robert and Matilda seemed very likely. Geoffrey and Matilda had secured much of Normandy. Together with Robert, they spent the beginning of the year gathering forces for a cross-Channel expedition. Matilda also appealed to the Pope at the start of the year. Her representative, Bishop Ulger, presented her legal claim to the English throne. He based it on her right by birth and the oaths sworn by the nobles. Arnulf of Lisieux presented Stephen's case. He argued that because Matilda's mother had really been a nun, her claim to the throne was not legitimate. The Pope refused to change his earlier support for Stephen. But from Matilda's point of view, the case usefully showed that Stephen's claim was disputed.

The Civil War (The Anarchy)

First Moves in the War

Empress Matilda's invasion finally began at the end of summer 1139. Baldwin de Redvers crossed from Normandy to Wareham in August. This was an attempt to capture a port for Matilda's invading army. But Stephen's forces made him retreat into the southwest. The next month, Matilda was invited by her stepmother, Queen Adeliza, to land at Arundel. On September 30, Robert of Gloucester and Matilda arrived in England with 140 knights. Matilda stayed at Arundel Castle. Robert marched northwest to Wallingford and Bristol. He hoped to gather support for the rebellion and meet up with Miles of Gloucester. Miles took the chance to break his loyalty to the King and declare for Matilda.

Stephen responded quickly by moving south. He besieged Arundel and trapped Matilda inside the castle. Stephen then agreed to a truce proposed by his brother, Henry of Blois. The full details of the agreement are not known. But the result was that Matilda and her knights were released from the siege. They were escorted to the southwest of England, where they reunited with Robert of Gloucester. The reasons for Matilda's release are still unclear. Stephen might have thought it was better to release the Empress and focus on attacking Robert. He might have seen Robert, rather than Matilda, as his main enemy at this point. Arundel Castle was also considered almost impossible to capture. Stephen might have worried about tying down his army in the south while Robert moved freely in the west. Another idea is that Stephen released Matilda out of a sense of chivalry. Stephen was known for being generous and courteous. Women were not usually targeted in Anglo-Norman warfare.

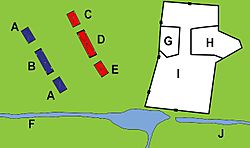

After staying for a while in Robert's stronghold of Bristol, Matilda set up her court in nearby Gloucester. This was still safely in the southwest but far enough away for her to remain independent of her half-brother. Although only a few new people had joined her side, Matilda still controlled a solid area of land. It stretched from Gloucester and Bristol south into Wiltshire, west into the Welsh Marches, and east through the Thames Valley as far as Oxford and Wallingford, threatening London. Her influence reached down into Devon and Cornwall, and north through Herefordshire. But her authority in these areas remained limited.

She faced a counterattack from Stephen. He started by attacking Wallingford Castle, which controlled the Thames area. It was held by Brian Fitz Count, and Stephen found it too well defended. Stephen continued into Wiltshire to attack Trowbridge. He took the castles of South Cerney and Malmesbury along the way. In response, Miles marched east. He attacked Stephen's forces at Wallingford and threatened to advance on London. Stephen was forced to give up his western campaign. He returned east to stabilize the situation and protect his capital.

At the start of 1140, Nigel, the Bishop of Ely, joined Matilda's side. Hoping to take East Anglia, he set up his base in the Isle of Ely. This area was surrounded by protective fenland. Nigel faced a quick response from Stephen. Stephen made a surprise attack on the isle, forcing the Bishop to flee to Gloucester. Robert of Gloucester's men retook some of the land that Stephen had taken in his 1139 campaign. To try and negotiate a truce, Henry of Blois held a peace conference at Bath. Matilda was represented by Robert. The conference failed after Henry and the clergy insisted that they should set the terms of any peace deal. Stephen's representatives found this unacceptable.

The Battle of Lincoln and Its Aftermath

Matilda's luck changed dramatically for the better at the start of 1141. Ranulf of Chester, a powerful northern noble, had fallen out with the King over the winter. Stephen had put Ranulf's castle in Lincoln under siege. In response, Robert of Gloucester and Ranulf advanced on Stephen's position with a larger force. This led to the Battle of Lincoln on February 2, 1141. The King commanded the center of his army. Alan of Brittany was on his right, and William of Aumale was on his left. Robert and Ranulf's forces had more cavalry. Stephen had many of his own knights get off their horses to form a strong infantry block. After an initial success where William's forces destroyed the Welsh infantry, the battle went well for Matilda's forces. Robert and Ranulf's cavalry surrounded Stephen's center. The King found himself surrounded by Matilda's army. After much fighting, Robert's soldiers finally defeated Stephen, and he was taken prisoner.

Matilda received Stephen in person at her court in Gloucester. Then she had him moved to Bristol Castle, which was used for important prisoners. Matilda now began to take the steps needed to be crowned queen. This would require the agreement of the Church and her coronation at Westminster. Stephen's brother Henry called a council at Winchester before Easter. As a papal representative, he was to consider the Church's view. Matilda had made a private deal with Henry. He would give her the Church's support in exchange for control over Church affairs. Henry gave her the royal treasury, which was quite empty except for Stephen's crown. He also removed many of her enemies from the Church if they refused to switch sides. However, Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury was not willing to declare Matilda queen so quickly. A group of clergy and nobles, led by Theobald, traveled to Bristol to see Stephen. Stephen agreed that, given the situation, he was prepared to release his subjects from their oath of loyalty to him.

The clergy gathered again in Winchester after Easter, on April 7, 1141. The next day, they declared that Matilda should be monarch instead of Stephen. She took the title "Lady of England and Normandy" as a step towards her coronation. Although Matilda's own followers attended the event, few other major nobles seemed to be there. The group from London delayed their decision. Stephen's wife, Queen Matilda, wrote to complain and demand her husband's release. Nevertheless, Matilda then went to London to arrange her coronation in June. Her position there became uncertain. Despite getting the support of Geoffrey de Mandeville, who controlled the Tower of London, forces loyal to Stephen and Queen Matilda remained close to the city. The citizens were afraid to welcome the Empress. On June 24, shortly before the planned coronation, the city rose up against the Empress and Geoffrey de Mandeville. Matilda and her followers fled just in time, making a chaotic retreat back to Oxford.

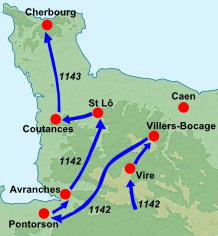

Meanwhile, Geoffrey of Anjou invaded Normandy again. With Waleran of Beaumont still fighting in England, Geoffrey took all the Duchy south of the River Seine and east of the Risle. No help came from Stephen's brother Theobald this time either. He seemed busy with his own problems with France. The new French king, Louis VII, had rejected his father's regional alliance. He improved relations with Anjou and took a more aggressive stance with Theobald. This would lead to war the following year. Geoffrey's success in Normandy and Stephen's weakness in England began to affect the loyalty of many Anglo-Norman nobles. They feared losing their lands in England to Robert and the Empress, and their possessions in Normandy to Geoffrey. Many started to leave Stephen's side. His friend and advisor Waleran was one of those who decided to switch sides in mid-1141. He crossed into Normandy to secure his family lands by allying himself with Matilda's family. He also brought Worcestershire into Matilda's camp. Waleran's twin brother, Robert of Leicester, effectively stopped fighting in the conflict at the same time. Other supporters of Matilda were given back their former strongholds, like Bishop Nigel of Ely. Still others received new earldoms in western England. The royal control over making coins broke down. This led to local nobles and bishops making their own coins across the country.

The Rout of Winchester and Siege of Oxford

Matilda's situation changed dramatically after her defeat at the Rout of Winchester. Her alliance with Henry of Blois did not last long. They soon argued over political favors and Church rules. The Bishop switched his support back to Stephen's side. In response, in July, Matilda and Robert of Gloucester besieged Henry of Blois in his castle at Winchester. They used the royal castle in the city as their base. Stephen's wife, Queen Matilda, had kept his cause alive in southeast England. The Queen, supported by her commander William of Ypres and reinforced with new troops from London, took the opportunity to advance on Winchester. Their forces surrounded Matilda's army. Matilda decided to escape from the city with Fitz Count and Reginald of Cornwall. The rest of her army delayed the royal forces. In the battle that followed, Matilda's forces were defeated. Robert of Gloucester himself was taken prisoner during the retreat. Matilda herself escaped, exhausted, to her fortress at Devizes.

With both Stephen and Robert held prisoner, talks were held to try and reach a long-term peace agreement. But Queen Matilda was unwilling to offer any compromise to the Empress. Robert refused to accept any offer to make him switch sides to Stephen. Instead, in November, the two sides simply exchanged the two leaders. Stephen returned to his queen, and Robert returned to the Empress in Oxford. Henry held another church council. It reversed its previous decision and confirmed Stephen's right to rule. A new coronation of Stephen and Matilda happened at Christmas 1141. Stephen traveled north to raise new forces and successfully convinced Ranulf of Chester to switch sides again. Stephen then spent the summer attacking some of the new castles built by Matilda's supporters the previous year. These included Cirencester, Bampton, and Wareham.

During the summer of 1142, Robert returned to Normandy to help Geoffrey with operations against some of Stephen's remaining followers there. He returned in the autumn. Matilda came under increasing pressure from Stephen's forces and was surrounded at Oxford. Oxford was a secure town, protected by walls and the River Isis. But Stephen led a sudden attack across the river, leading the charge and swimming part of the way. Once on the other side, the King and his men stormed into the town, trapping Matilda in the castle. Oxford Castle was a strong fortress. Instead of storming it, Stephen decided to settle in for a long siege. Just before Christmas, Matilda sneaked out of the castle with a few knights (probably through a secret gate). She crossed the icy river and escaped past the royal army on foot to Abingdon-on-Thames. Then she rode to safety at Wallingford. She left the castle soldiers to surrender the next day. Matilda and her companions reportedly wore white to blend in with the snow.

A Stalemate in the War

After the retreat from Winchester, Matilda rebuilt her court at Devizes Castle in Wiltshire. This was a former property of the Bishop of Salisbury that Stephen had taken. She set up her knights on the surrounding estates, supported by soldiers from Flanders. She ruled through local officials. Many of those who had lost lands in the areas held by the King traveled west to get support from Matilda. Supported by the practical Robert of Gloucester, Matilda was content to fight a long struggle. The war soon became a stalemate.

At first, the balance of power seemed to shift slightly in Matilda's favor. Robert of Gloucester besieged Stephen in 1143 at Wilton Castle, a gathering point for royal forces in Herefordshire. Stephen tried to break out and escape. This resulted in the Battle of Wilton. Once again, Matilda's cavalry proved too strong. For a moment, it seemed that Stephen might be captured for a second time. But he finally managed to escape. Later that year, Geoffrey de Mandeville, the Earl of Essex, rebelled against Stephen in East Anglia. Geoffrey based himself from the Isle of Ely and began a military campaign against Cambridge. He intended to move south towards London. Ranulf of Chester rebelled once again in the summer of 1144.

Meanwhile, Geoffrey of Anjou finished securing his control over southern Normandy. In January 1144, he advanced into Rouen, the capital of the Duchy, ending his campaign. Louis VII recognized him as Duke of Normandy shortly after.

Despite these successes, Matilda was unable to make her position stronger. Miles of Gloucester, one of her most talented military commanders, had died while hunting over the previous Christmas. Geoffrey de Mandeville's rebellion against Stephen in the east ended with his death in September 1144 during an attack on Burwell Castle in Cambridgeshire. As a result, Stephen made progress against Matilda's forces in the west in 1145. He recaptured Faringdon Castle in Oxfordshire. Matilda allowed Reginald, the Earl of Cornwall, to try new peace negotiations. But neither side was prepared to compromise.

Ending the War

The nature of the conflict in England slowly began to change. By the late 1140s, the major fighting in the war was over. It became a difficult stalemate, with only occasional outbreaks of new fighting. Several of Matilda's key supporters died. In 1147, Robert of Gloucester died peacefully. Brian Fitz Count slowly withdrew from public life, probably joining a monastery; by 1151 he was dead. Many of Matilda's other followers joined the Second Crusade when it was announced in 1145. They left the region for several years. Some of the Anglo-Norman nobles made individual peace agreements with each other to protect their lands and war gains. Many were not eager to continue the conflict.

Matilda's eldest son Henry slowly began to take a leading role in the conflict. He had stayed in France when the Empress first left for England. He crossed over to England in 1142, before returning to Anjou in 1144. Geoffrey of Anjou expected Henry to become the King of England. He began to involve him in governing the family lands. In 1147, Henry intervened in England with a small army of hired soldiers. But the expedition failed, mainly because Henry did not have enough money to pay his men. Henry asked his mother for money, but she refused. She said she had none available. In the end, Stephen himself paid off Henry's hired soldiers, allowing him to return home safely. His reasons for doing so are still unclear.

Matilda decided to return to Normandy in 1148. This was partly because of her difficulties with the Church. The Empress had occupied the very important Devizes Castle in 1142. She kept her court there. But legally, it still belonged to Josceline de Bohon, the bishop of Salisbury. In late 1146, Pope Eugene III intervened to support his claims. He threatened Matilda with being removed from the Church if she did not return it. Matilda first tried to delay, then left for Normandy in early 1148. She left the castle to Henry, who then delayed returning it for many years. Matilda re-established her court in Rouen. There, she met with her sons and husband. She probably made arrangements for her future life in Normandy and for Henry's next trip to England. Matilda chose to live in the priory of Notre Dame du Pré, just south of Rouen. She lived in private rooms attached to the priory and in a nearby palace built by Henry.

Matilda increasingly focused her efforts on governing Normandy, rather than the war in England. Geoffrey sent the bishop of Thérouanne to Rome in 1148 to argue for Henry's right to the English throne. Opinion within the English Church gradually shifted in Henry's favor. Matilda and Geoffrey made peace with Louis VII. In return, Louis VII supported Henry's rights to Normandy. Geoffrey died unexpectedly in 1151, and Henry claimed the family lands. Henry returned to England once again at the start of 1153 with a small army. He gained the support of some of the major regional nobles. However, neither side's army was eager to fight. The Church helped arrange a truce. A permanent peace followed. Under this treaty, Henry recognized Stephen as king. But Henry became Stephen's adopted son and successor. Meanwhile, Normandy faced considerable disorder and the threat of noble rebellion. Matilda was unable to completely stop this. Stephen died the next year, and Henry became king. His coronation used the grander of the two imperial crowns that Matilda had brought back from Germany in 1125. Once Henry had been crowned, the problems facing Matilda in Normandy disappeared.

Matilda's Later Life

Matilda spent the rest of her life in Normandy. She often acted as Henry's representative and helped govern the Duchy. Early on, Matilda and her son issued official documents in England and Normandy in their joint names. These dealt with various land claims that had come up during the wars. Especially in the first years of his reign, the King asked her for advice on how to rule. Matilda was involved in trying to help Henry and his Chancellor Thomas Becket when they argued in the 1160s. Matilda had originally warned against appointing Becket. But when a church leader asked her for a private meeting on Becket's behalf, she gave a balanced view of the problem. Matilda explained that she disagreed with Henry's attempts to write down English customs, which Becket also opposed. But she also criticized poor management in the English Church and Becket's own stubborn behavior.

Matilda helped deal with several diplomatic problems. The first involved the Hand of St James, a religious item Matilda had brought back from Germany many years before. Frederick I, the Holy Roman Emperor, believed the hand was part of the imperial treasures. He asked Henry to return it to Germany. Matilda and Henry insisted that it should remain at Reading Abbey. It had become a popular attraction for visiting pilgrims there. Frederick was paid off with other expensive gifts from England. These included a huge, luxurious tent, probably chosen by Matilda. Frederick used it for court events in Italy. She was also approached by Louis VII of France in 1164. She helped calm a growing diplomatic argument over how money for Crusades was being handled.

In her old age, Matilda paid more attention to Church matters and her personal faith. However, she remained involved in governing Normandy throughout her life. Matilda seemed to have a special fondness for her youngest son William. She opposed Henry's plan in 1155 to invade Ireland and give the lands to William. This was possibly because she thought the project was not practical. Instead, William received large grants of land in England. Matilda was more relaxed in her later life than in her youth. But a writer from Mont St Jacques, who met her during this time, still felt that she seemed to be "of the stock of tyrants."

Matilda's Death and Burial

Matilda died on September 10, 1167, in Rouen. Her remaining wealth was given to the Church. She was buried under the main altar at the abbey of Bec-Hellouin. The service was led by Rotrou, the archbishop of Rouen. Her tomb's epitaph (words on a tombstone) included the lines "Great by birth, greater by marriage, greatest in her offspring: here lies Matilda, the daughter, wife, and mother of Henry." This became a famous phrase among people at the time. This tomb was damaged in a fire in 1263 and later repaired in 1282. It was finally destroyed by an English army in 1421. In 1684, a group of monks identified some of her remaining bones. They reburied them at Bec-Hellouin in a new coffin. Her remains were lost again after the destruction of Bec-Hellouin's church by Napoleon. But they were found once more in 1846. This time, they were reburied at Rouen Cathedral, where they are today.

Matilda as a Ruler

Government and Court Life

In the Holy Roman Empire, young Matilda's court included knights, chaplains, and ladies-in-waiting. Unlike some queens of that time, she did not have her own personal chancellor to run her household. Instead, she used the imperial chancellor. When she acted as ruler in Italy, the local leaders were willing to accept a female ruler. Her Italian administration included the Italian chancellor, supported by experienced administrators. She was not asked to make any major decisions. Instead, she dealt with smaller matters and acted as a symbol for her absent husband. She met with and helped negotiate with important nobles and church leaders.

The Anglo-Saxon queens of England had held significant official power. But this tradition had lessened under the Normans. At most, their queens ruled temporarily as regents for their husbands when they were traveling, rather than ruling in their own right. When she returned from Germany to Normandy and Anjou, Matilda called herself Empress and the daughter of King Henry. As an Empress, her status was considered higher than all men in England and France in medieval society. When she arrived in England, her official seal showed the words "Matilda by the grace of God, Queen of the Romans." Matilda's seated portrait on her round seal made her different from other important English women. Their seals were usually oval with standing portraits. Men's seals usually showed them on horseback. Her seal did not show her on horseback, as a male ruler's would have. During the civil war for England, her status was uncertain. These unique features were meant to impress her subjects. Matilda also remained "daughter of King Henry." This status emphasized that her claim to the crown was inherited from her male relatives. She was the only legitimate child of King Henry and Queen Matilda. It also showed her mixed Anglo-Saxon and Norman background. It highlighted her claim as her royal father's only heir in a century when land ownership was increasingly passed down through families, especially to the oldest son.

In contrast to her rival Stephen and his wife Matilda of Boulogne—who were called "King of the English" and "Queen of the English"—Empress Matilda used the title "Lady of the English." There are several ways to understand the title "Lady." "Domina" is the female version of the title "dominus." This word could mean anything from the head of a household to an imperial title, translated as "master" or "lord." While "queen" implied only a king's wife, "lady" was used for a woman who held power on her own, like Æthelflæd of Mercia. It's important that Matilda's husband Geoffrey never used the equivalent title "lord of the English." At first, between 1139 and 1141, Matilda referred to herself as acting "alone," highlighting her independence from her husband. Also, it was common for newly chosen kings to use "lord" until their coronation as "king." The time in between was considered an interregnum (a period when there is no king). Since she was never crowned at Westminster, during the rest of the war, she seems to have used this title rather than that of the queen of England. However, some people at the time did call her by the royal title. In spring and summer 1141, when Matilda was effectively the ruling queen, some royal documents granting lands to Glastonbury Abbey and Reading Abbey described her as "Queen of the English." Another document mentions "my crown" and "my kingdom." While Marjorie Chibnall believed these instances of "Queen of the English" were either mistakes or not real, David Crouch thought this was unlikely to be a scribal error. He pointed out that Stephen's supporters had used "King of the English" before his formal coronation. He also noted that she was hailed as "queen and lady" at Winchester in March 1141, and that she "gloried in being called" the royal title. Nevertheless, the style "Lady of the English" remained more common in documents. The writer William of Malmsebury only calls her "lady."

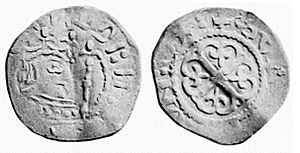

Matilda presented herself as continuing the English tradition of strong central government. She tried to maintain a government in England that ran parallel to Stephen's. This included a royal household and a chancellor. Matilda collected money from the royal lands in the counties she controlled, especially in her main territories where the sheriffs were loyal to her. She appointed earls to compete with those created by Stephen. However, she was unable to run a system of royal law courts. Her administrative resources were very limited, although some of her clerks later became bishops in Normandy. Matilda issued two types of coins in her name during her time in England. These were used in western England and Wales. The first coins were initially made in Oxford during her stay there. The design was then used by her mints at Bristol, Cardiff, and Wareham after her victory at the Battle of Lincoln. A second design was made at Bristol and Cardiff during the 1140s.

When she returned to Normandy for the last time in 1148, Matilda stopped using the title Lady of the English. She simply called herself Empress again. She never took the title of Countess of Anjou. Matilda's household became smaller. It often combined with Henry's own court when they were in Rouen together. She continued to play a special role in governing the area around Argentan. There, she held feudal rights from the grants made at the time of her second marriage.

Matilda's Church Relations

It's not clear how strong Matilda's personal religious faith was. However, people at the time praised her lifelong wish to be buried at the monastery of Bec rather than the grander but more worldly Rouen. They believed she had deep religious beliefs. Like other Anglo-Norman nobles, she gave a lot of support to the Church. Early in her life, she preferred the well-established Benedictine monastery of Cluny. She also supported some of the newer Augustinian orders, like the Victorines and Premonstratensians. As part of this support, she re-established the abbey of Notre-Dame-du-Vœu near Cherbourg.

As time went on, Matilda paid more attention to the Cistercian order. This order was very popular in England and Normandy during that period. It was dedicated to the Virgin Mary, a figure of special importance to Matilda. She had close ties to the Cistercian Mortemer Abbey in Normandy. She used monks from this house when she supported the founding of nearby La Valasse. She encouraged the Cistercians to build Mortemer on a grand scale. It included guest houses to host visitors of all ranks. She may have also helped choose the paintings for the monastic chapels.

Matilda's Legacy

How Historians See Matilda

Writers from England, France, Germany, and Italy at the time recorded many parts of Matilda's life. However, the only biography of her, seemingly written by Arnulf of Lisieux, has been lost. These writers had different opinions of her. In Germany, writers praised Matilda a lot, and her reputation as the "good Matilda" remained positive. During the years of the Anarchy, works like the Gesta Stephani had a much more negative tone. They praised Stephen and criticized Matilda. Once Henry II became king, the tone of the writers towards Matilda became more positive.

Scholars during the Tudor era were interested in Matilda's right to inherit the throne. By 16th-century standards, Matilda had a clear right to the English throne. So, academics struggled to explain why Matilda had accepted her son Henry's kingship at the end of the war, instead of ruling herself. By the 18th century, historians like David Hume understood much better the irregular nature of 12th-century law and customs. This question became less important. By the 19th century, old documents about Matilda's life, including charters, histories of foundations, and letters, were being found and studied. Historians Kate Norgate, Sir James Ramsay, and J. H. Round used these to create new, richer accounts of Matilda and the civil war. Ramsay's account, using the Gesta Stephani, was not flattering. Norgate, using French sources, was more neutral. The German academic Oskar Rössler's 1897 biography relied heavily on German documents, which English-speaking historians had not used much.

Matilda has received relatively little attention from modern English academics. She is often seen as a less important figure compared to others at the time, especially her rival Stephen. This is different from the work done by German scholars on her time in the Empire. Popular, but not always accurate, biographies were written by the Earl of Onslow in 1939 and Nesta Pain in 1978. But the only major academic biography in English remains Marjorie Chibnall's 1991 work. Interpretations of Matilda's personality have changed over time. But, as Chibnall describes, there is a "general agreement that she was either proud or at least keenly conscious of the high status of an empress." Like both Henry I and Henry II, Matilda had a certain powerful and grand manner. This was combined with a strong moral belief in her cause. Ultimately, however, she was limited by the political customs of the 12th century. The way modern historians have treated Matilda has been questioned by feminist scholars, including Fiona Tolhurst. They believe some traditional assumptions about her role and personality show bias based on gender. In this view, Matilda has been unfairly criticized for showing qualities that have been praised when seen in her male contemporaries.

Matilda in Popular Culture

The civil war years of Matilda's life have been featured in historical fiction. Matilda, Stephen, and their supporters appear in Ellis Peters's historical detective series about Brother Cadfael, set between 1137 and 1145. Peters shows the Empress as proud and distant, in contrast to Stephen, who is a tolerant and reasonable ruler. Matilda's reputation as a warrior may also have influenced Alfred, Lord Tennyson's decision to name his 1855 battle poem "Maud."

Matilda's Family Tree

Matilda's family tree:

See also

In Spanish: Matilde de Inglaterra para niños

In Spanish: Matilde de Inglaterra para niños