Concordat of Worms facts for kids

The Concordat of Worms was an important agreement between the Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire. It decided how bishops and abbots would be chosen in the Empire.

This agreement was signed on September 23, 1122, in Worms, Germany. Pope Callixtus II and Emperor Henry V made the deal. It ended the Investiture Controversy, a big fight between the government and the church. This fight was about who had the right to choose church leaders. It had been going on since the mid-1000s.

When Henry signed the agreement, he gave up his right to give bishops and abbots their special rings and staffs. These items were symbols of their church power. Church leaders would now be chosen by church rules. Pope Callixtus agreed that the emperor or his helpers could be at the elections. The emperor could also step in if there was a disagreement.

The emperor was still allowed to give bishops and abbots a scepter. This scepter was a symbol of the land and wealth that came with their church position.

Contents

Why the Conflict Started

In the mid-1000s, a group within the Christian Church wanted to make the Pope's power stronger. They wanted to reduce the power of European kings. In 1073, Pope Gregory VII became Pope. He made new rules to boost the Pope's authority. Some of these rules were written in a document called the Dictatus papae in 1075.

Gregory's rules said that kings and rulers had to answer to the Pope. He also said that kings could not choose church officials. This process was called "investiture."

Emperor Henry IV strongly disagreed with the Pope's ideas. He was used to choosing the bishops and abbots in his lands. This led to a big fight between the Empire and the Pope, known as the Investiture Controversy. The argument continued even after Pope Gregory VII died in 1084 and Henry IV gave up his throne in 1105.

Henry IV's son, Henry V, wanted to make peace with the church. But they could not find a lasting solution for the first 16 years of his rule. In 1111, Henry V made a deal with Pope Paschal II at Sutri. Henry would stop choosing clergy if the church gave back property that once belonged to the Empire. Henry hoped this deal would make Paschal agree to crown him emperor.

But the deal did not work. Henry then put the Pope in prison. After two months, Paschal promised to crown Henry and accept the emperor's role in choosing church leaders. He also agreed never to excommunicate Henry (kick him out of the church). Because these promises were made by force, church leaders kept fighting the Empire. The next year, Paschal broke his promises.

Efforts to Make Peace

Pope Paschal died in January 1118. Gelasius II became Pope but died a year later. Then, Callixtus II became Pope. He started talking with Emperor Henry V again to end the fight. In late 1119, two of the Pope's helpers met Henry in Strasbourg. The emperor generally agreed to stop giving new bishops and abbots their rings and staffs.

They planned a final meeting between Henry and Callixtus at Mouzon. But the meeting ended quickly. The emperor refused a last-minute change in the Pope's demands. Church leaders, meeting at a council in Reims, then excommunicated Henry. However, they did not fully support the Pope's demand that the emperor completely stop choosing church leaders. The talks failed.

Historians wonder if Callixtus truly wanted peace or if he just did not trust Henry. Callixtus had been very firm in 1111. His election as Pope might mean that the church leaders wanted to show strength to the emperor. They saw that Henry had problems with his own nobles. This made them think they could win completely.

More Talks Lead to a Deal

After the Mouzon talks failed, it became clear that Henry would not simply give up. Most church leaders then wanted to find a compromise. The strong arguments and statements that had been common during the Investiture Dispute had quieted down. Historian Gerd Tellenbach says that these years were "no longer marked by an atmosphere of bitter conflict."

This was partly because the Pope realized he could not fight two big battles at once. Callixtus had been involved in talks with the Emperor for ten years. He knew the situation well, making him the right person to try for an agreement. Historian Mary Stroll says the difference between 1119 and 1122 was not Henry. Henry had been willing to compromise in 1119. The difference was Callixtus, who had been unwilling then, but now wanted to reach a deal.

Many German nobles felt the same way. In 1121, nobles from the Lower Rhine and Duchy of Saxony, led by Archbishop Adalbert of Mainz, pressured Henry. Henry agreed to make peace with the Pope. In February 1122, Callixtus wrote to Henry in a friendly way. His letter was described as "a carefully crafted overture."

In his letter, Callixtus mentioned that they were related by blood. He said they should love each other like brothers. But he also said that German kings got their power from God through God's servants, not directly. Callixtus also said for the first time that he blamed Henry's bad advisors, not Henry himself, for the conflict. This was a big change from the Council of Reims in 1119. The Pope said the church gives what it has to all its children without making demands. This was meant to assure Henry that his position and Empire would be safe if they made peace.

Callixtus then spoke about spiritual matters. He asked Henry to remember that he was a king, but like all people, he had limits on Earth. He had armies and kings under him, but the church had Christ and the Apostles. He also hinted at Henry's excommunication (being kicked out of the church) by him. He begged Henry to allow peace to be made. This would increase the glory of the church, God, and the Emperor. But he also included a threat: if Henry did not change, Callixtus would put "the protection of the church in the hands of wise men."

Historian Mary Stroll says Callixtus took advantage of the situation. Callixtus was not strong militarily in the south and had problems with his own cardinals. Henry was also under pressure in Germany, both militarily and spiritually.

The Emperor replied through the Bishop of Speyer and the Abbot of Fulda. They went to Rome and met the Pope's helpers. One of Henry's representatives was from his political opponents in Germany. The other was a negotiator, not tied to one side. Things got complicated when there was a disputed election for the bishopric of Wurzburg in February 1122. This was exactly the kind of problem the Investiture Dispute was about. It almost started a civil war. But a truce was made in August, allowing the peace talks to continue.

In the summer of 1122, a meeting was held in Mainz. There, the emperor's helpers and church representatives agreed on the terms. The Pope showed he wanted the talks to succeed by announcing a big church council for the next year.

The Agreement at Worms

The Emperor welcomed the Pope's representatives in Worms with a formal ceremony. The actual talks seemed to happen in nearby Mainz, which was not friendly territory for Henry. So, he had to use messengers to keep up. Abbot Ekkehard of Aura wrote that discussions took over a week. On September 8, Henry met the Pope's representatives, and their final agreements were written down.

A possible compromise from England had been suggested, but it was not seriously considered. It included an oath of loyalty between the Emperor and Pope, which had caused problems in earlier talks. The Pope's group was led by Cardinal Bishop Lamberto Scannabecchi of Ostia, who later became Pope Honorius II.

Both sides looked at their past talks, including those from 1111, to see what had been agreed before. On September 23, 1122, the Pope's and Emperor's representatives signed documents outside the walls of Worms. There was not enough room in the city for all the people who came to watch. Adalbert, Archbishop of Mainz wrote to Callixtus about how hard the talks were. He said Henry believed the powers he was giving up were his by birthright as emperor. It is likely that almost every word of the final agreement was carefully chosen. The main difference from earlier talks was the Pope's willingness to make concessions.

The Concordat

The agreements made at Worms involved both sides giving things up and making promises. Henry, under oath to God, the apostles, and the church, gave up his right to give bishops and abbots their rings and staffs. He allowed church leaders to be chosen by church rules in his lands. He also recognized the traditional lands of the Pope as a legal area, not something the emperor could change. Henry promised to return church lands that he or his father had taken. He would also help the Pope get back lands taken by others. He promised to do the same for all other churches and nobles. If the Pope needed the Empire's help, he would get it. If the church came to the Empire for justice, it would be treated fairly. He also swore to stop "all investiture by ring and staff," ending an old imperial tradition.

Callixtus made similar promises about the Empire in Italy. He agreed that the emperor or his officials could be present at elections. He also gave the emperor the right to decide in cases of disputed election results, with advice from bishops. This was allowed as long as the elections were peaceful and fair. The emperor could also perform a separate ceremony. In this ceremony, he would give bishops and abbots their regalia, a sceptre. This scepter represented the imperial lands linked to their church position. This part also had a "cryptic" condition. Once the chosen bishop received this, he "should do what he ought to do according to imperial rights." In Germany, this happened before the bishop was officially made a bishop. In other parts of the empire (like Burgundy and Italy, but not the Papal States), it happened within six months. The Pope cared about the difference between Germany and other parts of the Empire. The papacy had felt more threatened by the Empire in Italy than elsewhere. Finally, the Pope gave "true peace" to the emperor and all who had supported him.

Callixtus had completely changed his strategy from the Mouzon talks. In Germany, choosing bishops would happen with very little change in the ceremony. The emperor would still be involved, but instead of "investiture," it was more like a loyalty ceremony, though the word "homage" was carefully avoided. Archbishop Adalbert, who first told Callixtus about the agreement, stressed that it still needed approval in Rome. This suggests that Adalbert and the Pope's helpers were against making concessions to the emperor. They probably wanted Callixtus to reject the deal. Adalbert believed the agreement would make it easier for the Emperor to scare bishop electors. He wrote that "through the opportunity of [the emperor's] presence, the Church of God must undergo the same slavery as before, or an even more oppressive one."

However, Stroll argues that Callixtus's concessions were "an excellent bargain." They removed the danger on the Pope's northern border. This allowed him to focus on the Normans to the south without threats. Historian Norman Cantor says the peace was achieved by letting local customs decide future relations between the king and the Pope. In most cases, this meant the king kept control over the church.

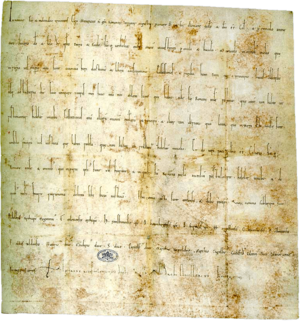

The agreement was published as two separate documents. Each one explained what one side was giving to the other. They are known as the Papal (or Calixtinum) and the Imperial (Henricianum) charters. Callixtus's document was addressed to the emperor in a personal way. Henry's was addressed to God. The bishop of Ostia gave the emperor a sign of peace from the Pope and held a church service. Through these actions, Henry was welcomed back into the church. The negotiators were praised for their difficult work, and the agreement was called "peace at the will of the pope." Neither document was signed. Both had unclear parts and unanswered questions, like the position of churches outside the Pope's lands and Germany. These questions were dealt with later, one by one. Historian Robert Benson suggests that the documents were short on purpose. He thinks the agreement is important for what it leaves out as much as for what it includes. For example, the word regalia meant two different things to each side. In Henry's document, it meant the loyalty owed to a king. In Callixtus's, it meant the church's lands and wealth. Bigger questions, like the relationship between the church and the Empire, were also not fully answered.

The Concordat was widely shared across Europe. Callixtus was not in Rome when the agreement arrived. He had left the city by late August and did not return until mid-October. He traveled to Anagni, taking the bishopric of Anagni and Casamari Abbey under his protection.

What Each Side Agreed To

| Agreement of Pope Callixtus II | Agreement of Emperor Henry V |

|---|---|

| I, Callixtus, Pope, grant to you, beloved son, Henry—Emperor of the Romans—that elections of bishops and abbots in the German kingdom will happen in your presence. There will be no unfair buying of positions or violence. If there is a dispute, you, with advice from other bishops, will help the side that is more in the right. The chosen person will receive their royal rights from you with a scepter and will perform their duties to you. But a person consecrated in other parts of your empire (like Burgundy and Italy) will receive their royal rights from you with a scepter within six months, without any demands. They will perform their duties to you (keeping all rights of the Roman Church). If you complain to me and ask for help, I will help you as my duty requires. I give true peace to you and to all who were on your side in this conflict. | In the name of the holy Trinity, I, Henry, Emperor of the Romans, for the love of God, the Holy Roman Church, and Pope Callixtus, and for my soul's salvation, give up to God, the holy apostles Peter and Paul, and the Holy Catholic Church, all power to choose church leaders using the ring and staff. I grant that in all churches in my kingdom or empire, there may be fair elections and free consecration. All the lands and royal rights of St. Peter that have been taken since this conflict began, whether by my father or me, and which I hold, I return to the Holy Roman Church. I will faithfully help get back what I do not hold. Also, the possessions of all other churches, nobles, and other people, both church and lay, that were lost in that war: I will return them as far as I hold them, according to the advice of the nobles or justice. I will faithfully help get back what I do not hold. I grant true peace to Pope Callixtus, the Holy Roman Church, and all who are or have been on its side. If the Holy Roman Church asks for help, I will grant it. If it complains to me, I will give it justice. All these things have been done with the agreement and advice of the nobles. Their names are listed here: Adalbert archbishop of Mainz; F. archbishop of Cologne; H. bishop of Ratisbon; O. bishop of Bamberg; B. bishop of Spires; H. of Augsburg; G. of Utrecht; Ou. of Constance; E. abbot of Fulda; Henry, duke; Frederick, duke; S. duke; Pertolf, duke; Margrave Teipold; Margrave Engelbert; Godfrey, count Palatine; Otto, count Palatine; Berengar, count.

I, Frederick, archbishop of Cologne and arch-chancellor, have approved this. |

How the Agreement Was Kept

The Concordat was officially approved at the First Council of the Lateran. The original document from Henry (the Henricianum) is kept at the Vatican Apostolic Archive. The Pope's document (the Calixtinum) has not survived, except in later copies. A copy of Henry's document is also in the Codex Udalrici, but it is a shorter version made for political reasons. It reduces the number of things the emperor gave up.

To show it was a victory for the Pope, Callixtus had a copy of the Henricianum painted on a wall in the Lateran Palace. While it showed the agreement as a papal victory, it also ignored the many things the Pope gave up to the emperor. This was part of what historian Hartmut Hoffmann called "a conspiracy of silence" about the Pope's concessions. In the painting, the Pope is shown sitting on a throne, and Henry is standing. This suggests they both used their power to reach this agreement. An English copy of the Calixtinum made by William of Malmesbury is mostly accurate. But it leaves out the part about using a scepter to grant the royal rights. He then criticized Henry's "German fury" but also praised him. He compared him to Charlemagne for his devotion to God and peace.

What Happened Next

The Concordat was first used not in the Empire, but by Henry I of England the next year. After a long fight between Canterbury and York that went to the Pope, Joseph Huffman says it would have been hard for the Pope to justify different rules for Germany and England. The Concordat completely ended the old "Imperial church system" where emperors had a lot of control.

The First Lateran Council was called to confirm the Concordat of Worms. This council was very large, with almost 300 bishops and 600 abbots from all over Catholic Europe. It met on March 18, 1123. One of its main goals was to make sure that local church leaders (diocesan clergy) were independent. To do this, it stopped monks from leaving their monasteries to provide spiritual care to people. This would now be only for the local church leaders. By approving the Concordat, the Council confirmed that bishops would be chosen by their clergy in the future. But, as the Concordat also said, the Emperor could refuse the loyalty of German bishops.

New rules were passed against simony (buying church positions), priests having partners, church robbers, and people who faked church documents. The council also confirmed special pardons for Crusaders. These rules, says C. Colt Anderson, "set important examples in church law that limited the influence of regular people and monks." While this led to a busy time of reform, it was important for those wanting change not to be confused with the many groups who were also criticizing the church.

The Concordat was the last major achievement for Emperor Henry. He died in 1125. An attempt to invade France in 1124 failed because of "strong opposition." Historian Fuhrmann says that Henry probably did not understand how important the events he lived through were. The peace only lasted until his death. When the nobles met to choose his successor, reformers tried to attack the emperor's gains from Worms. They argued that these gains were given to Henry personally, not to emperors in general.

However, later emperors, like Frederick I and Henry VI, still had a lot of power in choosing bishops. This was even more power than what Callixtus's document allowed them. Future emperors found the Concordat helpful enough that it stayed almost unchanged until the Empire was ended by Francis II in 1806 because of Napoleon. Popes also used the powers given to them in the Concordat to their advantage in later disagreements with their Cardinals.

Images for kids

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |