Angevin kings of England facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Angevins |

|

|---|---|

Arms adopted in 1198 |

|

| Parent house | House of Châteaudun |

| Country | England, France |

| Founder | King Henry II of England |

| Current head | Extinct |

| Final ruler | John, King of England |

| Titles |

|

The Angevins (pronounced AN-juh-vinz) were a powerful royal family from a place in France called Anjou. They ruled England and parts of France during the 12th and early 13th centuries. The most famous Angevin kings of England were Henry II, Richard I, and John.

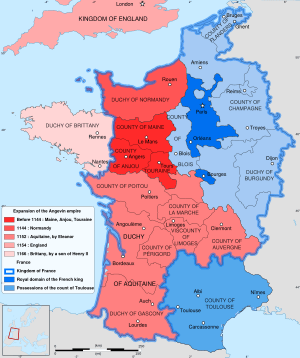

Henry II gained control of a huge amount of land in western Europe. This collection of lands was later called the Angevin Empire. It was different from the kingdoms that came before or after it. Henry's father, Geoffrey of Anjou, became the Duke of Normandy in 1144. In 1152, Henry married Eleanor of Aquitaine, which added even more land to his control. Henry also had a claim to the English throne through his mother, Empress Matilda. He became King of England in 1154 after King Stephen died.

Henry's third son, Richard, became king after him. Richard was known for being a great warrior, earning him the nickname "Lionheart." He was born in England but spent most of his adult life away from it. Despite this, Richard is still a very famous figure in both England and France. He is one of the few English kings remembered by his nickname instead of a number.

When Richard died, his younger brother John became king. John was Henry's fifth and last surviving son. In 1204, John lost many of the Angevins' lands in France, including Anjou, to the French king. Even though they lost Anjou, John and the kings after him were still known as dukes of Aquitaine. The loss of Anjou, which gave the family its name, meant John was the last Angevin king of England. However, some historians don't separate the Angevins from the Plantagenets. They see Henry II as the first Plantagenet king. The family line continued successfully through John until the time of Richard II. After that, it split into two rival branches: the House of Lancaster and the House of York. Later, in the 1600s, historians started using the name "Plantagenet" to describe the whole family.

Contents

Understanding Key Terms

What Does Angevin Mean?

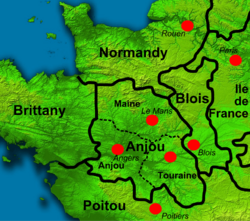

The word "Angevin" is often used in English history. It describes the kings who were also counts of Anjou, starting with Henry II. These kings were descendants of Geoffrey and Matilda. It also refers to their characteristics, their family members, and the time period from the mid-1100s to the early 1200s. The word "Angevin" can also describe anything related to Anjou or any ruler from there. As a noun, it means someone from Anjou or an Angevin ruler. Other rulers, like the ancestors of the three kings, their cousins who ruled Jerusalem, and later French royal family members, were also called Angevin.

What Was the Angevin Empire?

The term "Angevin Empire" was first used in 1887 by a historian named Kate Norgate. At the time these lands existed, there wasn't a single name for them. People would use long phrases like "our kingdom and everything under our rule." While the "Angevin" part of the name is generally accepted, the "empire" part has been debated. In 1986, a group of historians decided that there wasn't really an Angevin state or empire. However, they agreed that the term espace Plantagenet (Plantagenet area) was acceptable.

Who Were the Plantagenets?

Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York, chose "Plantagenet" as his family name in the 1400s. "Plantegenest" was a nickname for his ancestor Geoffrey in the 1100s. Geoffrey was the Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy. One popular idea is that the nickname came from the common broom plant. This plant has bright yellow flowers and was called genista in medieval Latin.

It's not clear why Richard chose this name. But during the Wars of the Roses, it helped show that he was a direct descendant of Geoffrey. Using the name for all of Geoffrey's male descendants became popular during the Tudor dynasty. This might have been because it gave more legitimacy to Richard's great-grandson, Henry VIII. By the late 1600s, this name was commonly used by historians.

Family Beginnings

The Angevin family line started with Geoffrey II, Count of Gâtinais and Ermengarde of Anjou. In 1060, they inherited the county of Anjou from an older family line. The marriage of Count Geoffrey to Matilda was very important. Matilda was the only surviving child of King Henry I of England. This marriage was part of a power struggle among different lords and kings in France during the 900s and 1000s.

From this marriage, Geoffrey's son, Henry, inherited claims to England, Normandy, and Anjou. This marked the beginning of the Angevin and Plantagenet dynasties. Geoffrey's father, Fulk V, had tried twice before to form an alliance with Normandy through marriage. His daughter Matilda married Henry I's heir, William Adelin, but William drowned in the White Ship. Fulk then married his daughter Sibylla to William Clito, another heir. But King Henry I had that marriage canceled to avoid strengthening William's claim to his lands.

How Inheritance Worked

In the 11th century, as society became more stable, new rules for inheritance developed. Daughters could now inherit important lands if there were no sons. A historian from the 1100s, Ralph de Diceto, noted that the counts of Anjou grew their power through marriage, not just by fighting. Geoffrey's marriage to Matilda, the king's daughter and a former empress, happened during this time.

It's not known if King Henry I planned for Geoffrey to be his heir. But the threat from William Clito made Henry's position weak. If the marriage had no children, King Henry probably would have chosen a relative like Stephen of Blois to succeed him. Stephen did, in fact, seize the English crown after Henry I died. King Henry I was very relieved in 1133 when Geoffrey and Matilda had a son, who was called "the heir to the Kingdom."

Later, a second son was born. This raised the question of whether the first son would get the mother's inheritance and the second son, Geoffrey, would get the father's. According to a historian named William of Newburgh, this plan didn't work out because Geoffrey died early in 1151. On his deathbed, Geoffrey decided that Henry should have both inheritances. This was so Henry would have enough resources to defeat Stephen. Geoffrey asked Henry to promise that once England and Normandy were secure, his younger brother Geoffrey would get Anjou. Henry's brother Geoffrey died in 1158, too soon to receive Anjou.

The unity of Henry's lands depended a lot on the ruling family. Many historians believe this made the "empire" unstable. French customs at the time often led to lands being divided among heirs. If Henry II's sons, Henry the Young King and Geoffrey of Brittany, hadn't died young, the inheritance would have been very different. Both Henry and Richard planned to divide their lands when they died. But they also tried to keep the lands together under one main ruler. For example, Henry tried to make Richard promise loyalty to his older brother for Aquitaine. Later, Richard took Ireland from John. This was complicated because the Angevins were also subjects of the kings of France. The French kings felt they had the right to loyalty from these lands. By the mid-1200s, there was a clear unified Plantagenet kingdom. But it couldn't be called an "Angevin Empire" anymore, as Anjou and most of the French lands had been lost.

The Angevins Arrive in England

King Henry I of England named his daughter Matilda as his heir. But when he died in 1135, Matilda was far away in France. Her cousin Stephen was closer, which gave him the chance to race to England and be crowned king. Matilda's husband Geoffrey wasn't very interested in England, but he started a long fight for control of Normandy.

To create another problem for Stephen, Matilda landed in England in 1139. This started a civil war known as the Anarchy. In 1141, she captured Stephen at the Battle of Lincoln, which made many of his supporters leave him. While Geoffrey conquered Normandy, Matilda lost her advantage because she was arrogant and not kind in victory. She even had to release Stephen in exchange for her half-brother. This allowed Stephen to regain control of much of England.

Geoffrey never came to England to help directly. Instead, he sent his son Henry, who was only 9 in 1142. The idea was that if England was conquered, Henry would become king. In 1150, Geoffrey also gave Henry the title of Duke of Normandy, but Geoffrey still held most of the power. Three lucky events helped Henry finally win the conflict:

- In 1151, Count Geoffrey died before he could divide his lands between his sons Henry and Geoffrey.

- Louis VII of France divorced Eleanor of Aquitaine. Henry quickly married her, which greatly increased his power and lands by adding Aquitaine.

- In 1153, Stephen's son Eustace died. Stephen, who had also recently lost his wife, gave up the fight. With the Treaty of Wallingford, he agreed to the peace offer Matilda had refused earlier. Stephen would be king for life, and Henry would be his successor. Stephen died soon after, and Henry became king in late 1154.

Henry faced many challenges to secure his lands. He needed to re-establish his authority over old territories and expand into new ones. In 1162, Theobald, the Archbishop of Canterbury, died. Henry saw this as a chance to regain control over the church in England. He appointed his friend Thomas Becket to be the new archbishop. However, Becket turned out to be a poor politician. His defiance angered the king and his advisors.

Henry and Becket argued many times over church property, Henry's brother's marriage, and taxes. Henry reacted by making Becket and other church leaders agree to 16 old customs. These rules, called the Constitutions of Clarendon, described the relationship between the king, his courts, and the church. When Becket tried to leave the country without permission, Henry tried to ruin him with lawsuits. Becket then fled into exile for five years.

Relations later improved, and Becket returned. But things went bad again when Becket saw the coronation of Henry's son as co-ruler by another archbishop as a challenge to his power. Becket then punished those who had offended him. When Henry heard this, he was very angry. Three of Henry's men killed Becket in Canterbury Cathedral after a failed attempt to arrest him. Many people in Europe believed Henry was involved in Becket's death. This act against the church made Henry an outcast. As a punishment, he walked barefoot into Canterbury Cathedral and was whipped by monks.

In 1171, Henry invaded Ireland. He was worried about the success of some knights he had allowed to recruit soldiers in England and Wales. These knights, including Strongbow, were becoming powerful rulers in Ireland. Pope Adrian IV had given Henry his blessing to expand his power into Ireland and reform the Irish church. Henry had originally planned to give some territory to his brother William, but William had died. Instead, Henry gave the lordship of Ireland to his youngest son, John.

In 1172, Henry II tried to give his youngest son John, who had no land, three castles as a wedding gift. This angered his 18-year-old son, Henry the Young King, who had not yet received any lands from his father. This led to a rebellion by Henry II's wife and three oldest sons. Louis VII supported the rebellion to weaken Henry II. William the Lion and other subjects of Henry II also joined the revolt. It took 18 months for Henry to force the rebels to surrender.

In 1182, Henry II gathered his children to plan how his lands would be divided after his death. His eldest son, Henry, would inherit England, Normandy, and Anjou. Richard would get Aquitaine. Geoffrey would get Brittany, and John would get Ireland. This plan led to more conflict. The younger Henry rebelled again before he died of dysentery. In 1186, Geoffrey died after a tournament accident. In 1189, Richard and Philip II of France took advantage of Henry's poor health. They forced him to accept humiliating peace terms, including naming Richard as his only heir. Two days later, the old king died, defeated and sad that even his favorite son John had rebelled. Many saw this as the punishment for Becket's murder.

The Angevin Decline

On the day of Richard's English coronation, there was a terrible attack on Jewish people. After his coronation, Richard put his lands in order. Then, in early 1190, he joined the Third Crusade to the Middle East. People had mixed opinions of Richard. He had angered the King of France's sister and taken over Cyprus. He had also insulted Leopold V, Duke of Austria and supposedly arranged the killing of Conrad of Montferrat. His cruelty was shown when he killed 2,600 prisoners in Acre. However, Richard was also respected for his military leadership and polite manners. Despite winning battles in the Third Crusade, he failed to capture Jerusalem. He returned from the Holy Land with only a few followers.

Richard was captured by Leopold on his way home. He was then handed over to Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor. A large tax was needed to pay his huge ransom. Philip II of France had taken over Normandy, and John of England controlled much of Richard's remaining lands. However, when Richard returned to England, he forgave John and regained control. Richard left England for good in 1194. He fought Philip for five years to get back the lands Philip had seized while Richard was imprisoned. Just as he was about to win, he was wounded by an arrow during a siege and died ten days later.

Richard's failure to have an heir caused a problem with who would rule next. Anjou, Brittany, Maine, and Touraine chose Richard's nephew Arthur as their ruler. But John became king in England and Normandy. Philip II of France again tried to cause trouble in the Plantagenet lands in Europe. He supported his vassal Arthur's claim to the English crown. Eleanor supported her son John, who won a battle and captured the rebel leaders.

Arthur was killed (some say by John), and his sister Eleanor spent the rest of her life in prison. John's actions made many French nobles side with Philip. The rebellions by Norman and Angevin nobles ended John's control of his lands in France. This was the end of the Angevin Empire in practice, though Henry III would continue to claim these lands until 1259.

After regaining his power in England, John planned to retake Normandy and Anjou. He wanted to draw the French army away from Paris while another army attacked from the north. However, his allies were defeated at the Battle of Bouvines. This was one of the most important battles in French history. John's nephew retreated and was soon overthrown. John agreed to a five-year truce. Philip's victory was very important for the political order in England and France. The battle helped establish strong, absolute rule in France.

John's defeats in France weakened his position in England. His English nobles rebelled, which led to the signing of Magna Carta. This document limited the king's power and established common law. It became the basis for many constitutional battles in the 1200s and 1300s. The nobles and the king failed to follow Magna Carta. This led to the First Barons' War, where rebel nobles invited Prince Louis to invade.

Many historians use John's death and William Marshal's appointment as protector for the nine-year-old Henry III to mark the end of the Angevin period. This also marks the beginning of the Plantagenet dynasty. Marshal won the war with victories in 1217, leading to a peace treaty where Louis gave up his claims. After the victory, the Marshal Protectorate reissued Magna Carta as the basis for future government.

Lasting Impact

The Plantagenet Family

Historians often say that the invasion by Prince Louis marks the end of the Angevin period. It also marks the start of the Plantagenet family's rule. The war was still uncertain when John died. William Marshal saved the family by winning battles and forcing Louis to give up his claim. However, Philip had captured all the Angevin lands in France except for Gascony. This collapse happened for several reasons. These included changes in economic power, growing cultural differences between England and Normandy, and the fragile nature of Henry's empire. Henry III tried to get back Normandy and Anjou until 1259. But John's losses in France and the rise of French power were a "turning point in European history."

Richard of York adopted "Plantagenet" as a family name for himself and his descendants in the 1400s. "Plantegenest" was a nickname for Geoffrey, and his symbol might have been the common broom plant. It's not clear why Richard chose the name. But it showed his high status as a direct descendant of Geoffrey and six English kings during the Wars of the Roses. Using the name for Geoffrey's male descendants became popular during the Tudor period. This might have been because it gave more legitimacy to Richard's great-grandson Henry VIII of England.

Family Tree

Through John, many people are descended from the Angevins, including all later kings and queens of England and the United Kingdom. John had five children with Isabella:

- Henry III – King of England for most of the 1200s.

- Richard – a famous European leader and King of the Romans.

- Joan – married Alexander II of Scotland, becoming his queen.

- Isabella – married the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II.

- Eleanor – married William Marshal's son and later, the English rebel Simon de Montfort.

John also had children with other women. The most famous was Joan, who married Prince Llywelyn the Great of Wales.

What People Thought Then

A historian named Gerald of Wales used parts of a legend to say the Angevins had a demonic origin. The kings were said to joke about these stories.

Henry was often criticized by people at the time, even in his own court. However, William of Newburgh, writing after Henry's death, said that "the experience of present evils has revived the memory of his good deeds." He added that Henry, who was hated in his own time, was now seen as an excellent ruler. Henry's son Richard's image was more complex. He was the first king who was also a knight. He was known as a brave and skilled military leader. But historians criticized him for taxing the church for the Crusade and his ransom, as church members were usually exempt from taxes.

Historians like Richard of Devizes and William of Newburgh were generally not kind to John's behavior when Richard was king. But they were more understanding of the early years of John's rule. Accounts of his later years are limited. His bad reputation was set by two historians writing after his death. One even claimed John tried to convert to Islam, but modern historians don't believe this.

Impact on Government

Many changes Henry made during his rule had long-lasting effects. His legal changes are part of the basis for English law. Henry's traveling judges also influenced legal reforms in other countries. Henry's actions in Brittany, Wales, and Scotland had a big impact on their societies and governments. John's reign, despite its problems, and his signing of Magna Carta, were seen by some historians as positive steps. They believed it helped England's government and economy develop. Magna Carta was reissued and became a foundation for future government.

Buildings, Language, and Books

There wasn't a special Angevin or Plantagenet culture that made them different from their neighbors. A historian recorded that Henry built or renovated castles throughout his lands. However, these buildings didn't have a unique style. Similarly, there wasn't a single type of literature among the different languages spoken, such as French, English, and Occitan. French was the main language for the powerful, and Latin was used by the church.

The Angevins were closely connected to the Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou. Henry's aunt was the Abbess, and Eleanor retired there to be a nun. The abbey was originally where Henry, Eleanor, Richard, his daughter Joan, and John's wife were buried. Henry III visited the abbey in 1254 to rearrange these tombs.

How Historians See Them

According to historian John Gillingham, Henry and his rule have interested historians for many years. Richard is remembered mostly for his military actions. Historian Steven Runciman wrote that Richard "was a bad son, a bad husband, and a bad king, but a gallant and splendid soldier."

In the 1700s, historian David Hume wrote that the Angevins were key to creating a truly English monarchy. Interpretations of Magna Carta have changed. While its symbolic value for later generations is clear, most historians see it as a failed peace agreement. John's opposition to the Pope and his support for royal rights made him popular with the Tudors in the 1500s. Some saw John as an early Protestant hero. Later Protestant historians also praised Henry's role in Thomas Becket's death and his arguments with the French.

More access to old records in the late 1800s led to a recognition of Henry's contributions to English law. William Stubbs called Henry a "legislator king" because of his major reforms in England. In contrast, Stubbs called Richard "a bad son, a bad husband, a selfish ruler, and a vicious man."

The growth of the British Empire led historian Kate Norgate to research Henry's lands in Europe. She created the term "Angevin Empire" in the 1880s. However, historians in the 1900s challenged many of these ideas. In the 1950s, historians focused on the nature of Henry's "empire." French scholars, in particular, looked at how royal power worked during this time. Historians began to combine British and French views of the period in the 1980s.

Detailed study of Henry's records has raised doubts about earlier interpretations. There are still big gaps in understanding Henry's rule in Anjou and southern France.

During the Victorian period, interest in the morality of historical figures grew. This led to more criticism of Henry's behavior and Becket's death. Historians focused on John's character. Norgate wrote that John's downfall was not due to his military failures but his "almost superhuman wickedness."

Historians today have different opinions. Some argue that John's failures were exaggerated by historians in the 1100s and 1200s. Others say that modern historians have been too kind in judging John's flaws.

In Popular Culture

Henry II appears as a character in several modern plays and films. He is a main character in James Goldman's play The Lion in Winter (1966). This play shows an imaginary meeting between Henry's family and Philip Augustus. In the 1968 film, Henry is a strong and determined king. Henry also appears in Jean Anouilh's play Becket, which was filmed in 1964. The conflict with Becket is also the basis for T. S. Eliot's play Murder in the Cathedral.

During the Tudor period, John was often shown in plays. He appeared as a "proto-Protestant martyr" in plays like The Troublesome Reign of King John. John Bale's play Kynge Johan showed John trying to save England from the "evil agents of the Roman Church." Shakespeare's play King John shows John as both a victim of Rome and a weak ruler.

Richard is the subject of two operas. In 1719, George Frideric Handel used Richard's invasion of Cyprus for his opera Riccardo Primo. In 1784, André Grétry wrote Richard Coeur-de-lion.

Robin Hood Stories

The earliest stories of Robin Hood usually linked him to a king named "Edward." But around the 1500s, Robin Hood tales started to mention him as a supporter of Richard. Robin became an outlaw during John's bad rule, while Richard was away on the Third Crusade. Later plays focused on John's unfair rule. Unfavorable depictions of John in the 1800s were influenced by Sir Walter Scott's novel Ivanhoe. These, in turn, influenced Howard Pyle's The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (1883), which made John the main villain. In the 1900s, John also appeared in Robin Hood books and films. In the 1922 film, John does terrible things. In the 1938 version with Errol Flynn, John is shown as weak and cowardly. This film trend made John highlight Richard's good qualities. In the Disney cartoon version, John is a "cowardly, thumbsucking lion."

Medieval Legends

During the 1200s, a folktale grew about Richard's minstrel Blondel. The story says Blondel traveled around singing a song only he and Richard knew to find Richard's prison. This story inspired an opera and the opening of a film version of Ivanhoe. Tales from the 1500s about Robin Hood began to describe him as living at the same time as Richard the Lionheart. Robin became an outlaw during the rule of Richard's evil brother, John, while Richard was fighting in the Third Crusade.

See Also

- Angevin Empire, for further information on the Angevin domains

- House of Plantagenet, for details on the successors of the Angevins and the wider family

- Capetian House of Anjou and Valois House of Anjou, other dynasties called "Angevin" by some historians

- Treaty of Louviers, for a peace agreement between King Richard I of England and King Philip II of France

- Capetian-Plantagenet rivalry, for an overview of the conflict between Henry II and his descendants against the Kings of France

Images for kids