Pope Adrian IV facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Pope Adrian IV |

|

|---|---|

| Bishop of Rome | |

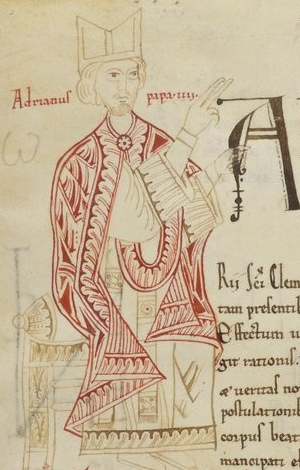

Adrian IV depicted in the Chronicle of Casauria, second half of the 12th century

|

|

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Papacy began | 4 December 1154 |

| Papacy ended | 1 September 1159 |

| Predecessor | Anastasius IV |

| Successor | Alexander III |

| Orders | |

| Created Cardinal | 1146 |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Nicholas Breakspear |

| Born | c. 1100 Abbots Langley, Hertfordshire, England |

| Died | 1 September 1159 (aged 58–59) Anagni, Papal States, Holy Roman Empire |

| Other Popes named Adrian | |

Pope Adrian IV, born Nicholas Breakspear around 1100, was the leader of the Catholic Church and the ruler of the Papal States from 1154 until his death in 1159. He is famous for being the only Englishman ever to become pope.

Adrian was born in Hertfordshire, England. Not much is known about his early life. As a young man, he traveled to southern France. There, he studied law in Arles and later joined a religious community called the St Ruf Abbey in Avignon. He became a canon regular, which is a type of priest, and eventually became the abbot, or head, of the abbey.

He visited Rome several times and caught the attention of Pope Eugene III. Eugene sent him on important missions, including one to Catalonia. There, Christians were trying to reclaim land from Muslim rule in a period known as the Reconquista. Around 1149, because his monks complained he was too strict, Pope Eugene made him the Bishop of Albano. This allowed Eugene to use Breakspear's skills as a diplomat.

As a bishop, Adrian went on another diplomatic trip to Scandinavia. He helped reorganize the Church in Norway during a civil war. He then moved to Sweden, where people admired him greatly. When he left, writers of the time called him a saint. Breakspear returned to Rome in 1154. The previous pope had just died. Breakspear was then chosen by the cardinals to be the next pope.

However, Rome was in a difficult political state. There were many people who wanted the city to be a republic, not ruled by the pope. Adrian quickly brought back the pope's authority in Rome. But his relationship with the new Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick I, started badly and got worse. Adrian then made an alliance with the Byzantine emperor, Manuel I Komnenos. Manuel wanted to regain control in southern Italy, which was then ruled by the Norman kings of Sicily, led by William I.

Adrian's alliance with the Byzantine emperor did not work out. King William defeated Manuel's forces. This forced Adrian to make peace with William at the Treaty of Benevento. This made Emperor Frederick even angrier, as he saw it as Adrian breaking their earlier agreement. Relations got worse when Frederick claimed large areas of northern Italy. Adrian's ties with England, his home country, remained good. He gave many special rights to St Albans Abbey. He also supported King Henry II of England's plans when he could. Most famously, in 1158, Adrian supposedly gave Henry a special permission called the papal bull Laudabiliter. This document is believed to have allowed Henry to invade Ireland. However, Henry did not invade for another 14 years, and historians are still not sure if the bull truly existed.

After Adrian's death in Anagni, there was disagreement over who should be the next pope. Cardinals who supported the emperor voted for one candidate, and those against the emperor voted for another. While Pope Alexander III officially took over, another pope was also elected by the opposing side. This led to a long split in the Church that lasted 22 years. Historians have studied Adrian's time as pope a lot. Many good things happened, like his building projects and improving the pope's finances. He faced powerful challenges but managed them well, even though he couldn't completely overcome them.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Political Challenges for the Pope

- Becoming Pope in 1154

- Restoring Order in Rome

- Imperial Conflict at Sutri in 1155

- Normans, Greeks, and Apulians

- Problems with Translation in 1157

- Imperial Claims in Northern Italy

- Relations with England

- Actions as Pope

- Pope Adrian's Beliefs and Views

- Personality

- Death

- Events After Adrian's Death

- Legacy and Impact

- See also

Early Life and Education

Nicholas Breakspear came from a simple family. The exact year he was born is not known, but he was probably around 55 when he became pope. Not much is known about his childhood. He was likely born near St Albans in Hertfordshire, England. Some stories about his early life might be legends from the great abbey there. It's thought he was born in a small village called Bedmond. Most of what we know comes from writers like Cardinal Boso and William of Newburgh, who wrote about him more than 30 years after his death. This means there isn't much clear information, especially dates, about Breakspear's life before he became pope.

The English writer Matthew Paris said Nicholas came from Abbots Langley. Paris also said Nicholas's father was a priest who later became a monk. This might mean Nicholas was born outside of marriage. Nicholas had a brother named Ranulf or Randall, who was a clerk in Essex. Paris is also the source for his last name, Breakspear.

Paris tells a story that Nicholas was turned away from St Albans Abbey when he wanted to become a monk. However, this story isn't quite right because the abbot mentioned didn't start his role until much later. Still, this story helped St Albans feel proud of the local boy who became pope. William of Newburgh wrote that Nicholas was too poor for much schooling. He likely traveled to France to learn how to be a clerk, which was a common way for people to get ahead in the 1100s. He might have become a canon at a priory in Merton, Surrey, before going to France.

Moving to France and Becoming a Leader

Nicholas Breakspear can be clearly identified next in Arles, a town in southern France. There, he continued his studies in canon law, which is church law. He probably also studied Roman law. After finishing his studies, he became a canon regular at the St Ruf priory in Avignon, about 40 kilometers (25 miles) north of Arles. He quickly became the prior, or second-in-command, and then the abbot of St Ruf.

While he was still a canon, he seems to have written a legal document in Barcelona in 1140. However, there were complaints that he was too strict, and the monks rebelled against him. Because of this, he was called to Rome. A temporary peace was made, but the monks rebelled again soon after. Breakspear might have visited Rome three times while at St Ruf. Each visit brought him more success, but also took many months of his time.

It was during his time at St Ruf that Breakspear caught the attention of Pope Eugenius III. Eugenius saw his strong leadership qualities. In 1147, Eugenius met with "N. abbot of St Rufus." It was probably in 1148 that Breakspear met John of Salisbury, who would become a good friend. Soon after, Eugenius made him a Cardinal-Bishop of Albano. This made Adrian only the second Englishman to reach such a high rank. He attended an important church meeting, the Council of Reims, in November 1148. Pope Eugenius might have promoted Breakspear to solve the monks' complaints. He told them to choose a new abbot they could live with peacefully, as Breakspear would no longer be their burden. Later, when Breakspear became pope, he showed great favor to St Ruf. For example, he allowed them to send people to Pisa Cathedral to get stone and columns for building.

Some historians wonder why Breakspear was promoted so quickly. His abbey was not well-known, and his reasons for visiting the papal court were often because of complaints about his behavior. However, his earlier time at Merton might explain it. The Cardinal Bishopric of Albano was a very important position, close to the pope. His quick rise to such a sensitive role shows that Eugenius must have seen special qualities in him.

Breakspear's journey to northern Europe is one of the best-documented parts of his life. When he arrived, Norway was in a civil war. The king, Inge I, was not strong or respected. Breakspear helped bring peace between the fighting groups, at least for a while. He also helped restore the monarchy. His main goals were likely to divide the Archbishopric of Lund, which covered both Norway and Sweden, into two separate national church regions. He also wanted to arrange payments to the pope (called Peter's Pence) and reorganize the church in Scandinavia to be more like the church in Italy and other parts of Europe.

Breakspear might have traveled to Norway through France and England. His arrival seemed unexpected. The Archbishop of Lund was away, and the King of Norway was on a military campaign. His first stop was Norway. Breakspear held a council in Nidaros. This council helped strengthen the church's finances and the social standing of the clergy.

Nidaros, which was important for the worship of St Olaf, had only been a bishopric until then. Adrian's council aimed to establish church laws. He made Nidaros a large church province, covering all of Norway, Iceland, Greenland, and the Faroe, Orkney, and Shetland Islands. Breakspear also approved the expansion of what would become Europe's northernmost and largest medieval cathedral, Trondheim Cathedral. While in Norway, he founded three cathedral schools. His work in Norway earned him praise from the Icelandic writer Snorri Sturluson.

After the Nidaros council, Breakspear sailed to Sweden. His work there was similar to Norway. He held another council in Linköping, which reorganized the Swedish church under the Archbishop of Lund. He also got permission from the Swedish king to introduce Peter's Pence and reduce the influence of ordinary people on the church. His visit to Sweden was recorded by writers of the time. Adrian tried to create a main church center for Sweden, but one of the provinces, Gothland, opposed it. This plan did not happen. Breakspear seemed surprised by this conflict. He later repaired relations with Archbishop Eskil, who had lost half his church area. Breakspear put Eskil in charge of the new Swedish church region.

Historians describe Adrian's mission in the north as a great success. He was even seen as the "apostle of Scandinavia." He brought peace to the kingdoms, law to the people, and order to the churches. He successfully introduced a new payment to St Peter, which showed the Scandinavian church accepted the pope's authority. He left Scandinavia in the autumn of 1154. He left a good impression, with one later story calling him "the good cardinal...now considered a saint." When he returned to Rome, he found that the previous two popes had died. The cardinals were looking for a new leader.

Political Challenges for the Pope

At this time, the pope was not fully in control of his own city. There were many new ideas, and ordinary people were gaining more power, challenging the traditional spiritual leaders.

Pope Eugenius had died in July 1153. His successor, Anastasius IV, was old and only ruled for a year. Anastasius died on December 3, 1154, just as Breakspear returned to Rome. A powerful new figure had also appeared: Frederick Barbarossa, who became the Holy Roman Emperor in 1152. Barbarossa and Pope Eugenius had made an agreement, the Treaty of Constance, to work together against King William of Sicily and the Roman Commune.

Adrian faced four main problems when he became pope. First, the city of Rome was controlled by Arnold of Brescia. Second, the new emperor, Frederick, was marching towards Rome for his coronation. Third, the Byzantine emperor had recently invaded southern Italy. Fourth, the pope's own vassals, or loyal nobles, in his lands were restless.

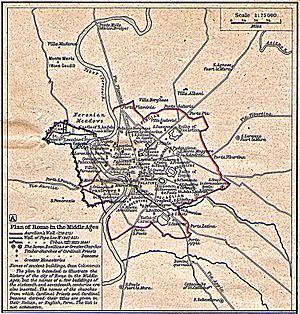

By the time Adrian became pope, Rome was a major player in politics. Since 1144, it had been governed by a republican commune, which was hostile to the pope. Arnold of Brescia, who was considered a heretic by the Church, had ruled Rome since 1146 and was very popular. His popularity meant people were hostile towards the popes. The pope's power in Rome was weak. The nobles in the pope's lands did not always obey Rome and had to be convinced or forced to return their loyalty. Papal politics faced problems both at home and abroad. The election of Adrian IV, and the popes before him, happened during this time of revolution in Rome.

Adrian inherited the Treaty of Constance from Eugenius. This treaty was a "mutual assistance pact" with the Emperor. For the popes, the most important part was that the emperor's crowning depended on Arnold of Brescia being expelled from Rome. It also promised each side support against King William in Sicily and the Byzantine Empire. Adrian confirmed this treaty in January 1155.

Pope Eugenius believed in Papal supremacy, meaning the pope had the highest authority. He said Christ gave St Peter the keys to heaven, and power over both earthly and heavenly empires. From the start of his reign, Barbarossa wanted to present himself as the heir to the Roman Emperors, seeing his empire as a continuation of theirs.

Historians say that despite public statements, the pope and emperor were often against each other for many years. No peace treaty could unite them for long. The idea of the "two swords of Christendom" (spiritual and earthly power working together) was gone. This situation was very difficult for the pope, and Adrian had to navigate it carefully.

The Eastern Emperor, Manuel I Komnenos, wanted to reunite both the Eastern and Western Roman Empires under one crown. He wanted to be crowned by the pope in Rome, just like Western emperors. The death of King Roger II of Sicily gave Manuel a chance to act. Roger II had ruled Sicily strictly, and his nobles were unhappy. His son, William, was less interested in governing, so the nobles rebelled when Roger died in 1154. This was important to the pope because the rebels were willing to ally with anyone against William.

Becoming Pope in 1154

Nicholas Breakspear was in the right place at the right time. This led to his election as pope on December 4, 1154. However, he also had special qualities, as shown by his trip to Scandinavia. He was described as rising "as if from the dust to sit in the midst of princes." Events moved quickly because the papacy was in a big crisis. Adrian was officially seated on December 5 and crowned in St Peter's Basilica on December 6. His election was seen as a unanimous agreement by the cardinals. To this day, Adrian is the only English pope. He was one of the few popes of his time who didn't need to be consecrated, or made holy, because he was already a bishop.

According to one account, Breakspear had to be forced to take the papal throne. He chose the name Adrian IV, possibly to honor Adrian I, who respected St Alban and gave special rights to St Albans Abbey. It was a smart choice, as the papacy needed energy and strength. Even though he was elected unanimously by the cardinals, the people of Rome were ignored. This meant relations between the pope and his city were bad from the start. Relations were also poor with the King of Sicily, who controlled much of southern Italy.

The situation with the Roman Commune was so bad that Adrian had to stay in the Leonine City, a walled area around St Peter's. He couldn't immediately complete his enthronement ceremony, which traditionally involved a grand entry into Rome itself. He had to stay there for the next four months. So, even though he was consecrated, he wasn't crowned in the traditional ceremony at the Lateran Palace, which would have given him feudal title to the papal lands. Because of problems with the Romans, he probably didn't receive his crown until the following Easter.

Restoring Order in Rome

Because Arnold of Brescia was in Rome, Adrian couldn't perform some important religious ceremonies. Soon after Adrian was elected, Roman republicans badly beat up a cardinal. Adrian was no more popular with the people or the Roman Commune than the popes before him. So, at Easter the next year, he left for Viterbo. His main goal was to control Emperor Frederick Barbarossa. Barbarossa had just become emperor, and for their own reasons, the pope and emperor needed each other. Adrian needed Barbarossa's military help against William, the King of Sicily, who was threatening the pope's lands. The emperor, in turn, needed Adrian to perform the traditional imperial coronation ceremony.

Adrian took a strong stance against the Roman commune. He threatened to place the city under an interdict, which meant no church services could be held, for protecting Arnold. This strategy worked. It created a division between the commune and Arnold, who was then expelled. Adrian followed through with his threat after one of his cardinals was beaten on the Via Sacra. This was a very brave act, considering Adrian was a foreign pope who had only been in office for a few weeks. He knew little about the city and its people, who were becoming more hostile to outsiders, and he had little popular support. Rome was forced to submit to the pope, and Arnold of Brescia was expelled. Although Adrian managed to restore the pope's authority in the city, he couldn't completely get rid of the idea of a republic, and the commune remained the governing body.

Imperial Conflict at Sutri in 1155

Frederick Barbarossa had received the Iron Crown of Lombardy, making him King of Italy. But he also wanted his Imperial Crown from the pope. Adrian initially saw the emperor as the church's protector.

To achieve this, Adrian and Barbarossa met at Sutri in early June 1155. This meeting quickly became a major struggle for power and influence. An Imperial writer reported that Adrian, with the whole Roman Church, met them joyfully and offered holy consecration. He also complained about the troubles he had faced from the Roman people.

Adrian might have been surprised by the emperor's quick arrival in Italy and his fast approach to Rome. The conflict began when Barbarossa refused to act as the pope's strator. This meant he wouldn't lead the pope's horse by the bridle or help Adrian dismount, as was traditionally expected. In response, the pope refused to give the emperor the "kiss of peace." The emperor was still willing to kiss Adrian's feet, though. These might seem like small insults, but in a time when symbolic actions were very important, they took on greater political meaning.

The confusion at Sutri might have been accidental. But Frederick was also offended by a painting in the Lateran Palace. It showed his predecessor, Emperor Lothar, as a liegeman, or loyal servant, of the pope. Barbarossa politely complained to the pope. He wrote in a letter, "it began with a picture. The picture became an inscription. The inscription seeks to become an authoritative utterance. We shall not endure it, we shall not submit to it." Adrian told Barbarossa he would have it removed, so that "so trifling a matter might afford the greatest men in the world an occasion for dispute and discord." However, Adrian did not remove it. By 1158, Imperial writers were calling the painting and its inscription the main cause of the conflict between the pope and emperor. Adrian was confused by the emperor's refusal to perform the squire service. He dismounted and sat on a folding stool. Barbarossa, if he wanted to be crowned, had limited options against the pope. He sought advice from his counselors, looking at old records and accounts of past ceremonies. A whole day was spent examining old documents and hearing from those who had been present at the 1131 coronation. The pope's side saw this as a sign of aggression and left Adrian for the safety of a nearby castle.

Imperial Coronation in 1155

The emperor was eventually convinced to perform the necessary services. He was crowned in Nepi on June 18. Peace was kept at Nepi, and both the pope and emperor dined together, wearing their crowns to celebrate the Feast of Saints Peter and Paul. There was much celebration, with some saying that "a single state had been created from two princely courts." However, some historians argue that the emperor's power was clearly less than the pope's. Adrian himself made it even less in his version of the coronation ceremony. There was also no official enthronement for the new emperor.

This ceremony was a new version of the traditional one. It highlighted the difference between anointing a regular person and a priest. Before, emperors were anointed on the head, like a priest. This time, Adrian anointed Barbarossa between the shoulders. Also, the pope gave him a sword. This emphasized the emperor's role, as Adrian saw it, as the defender of the papacy and its rights. Adrian, however, did not allow his officials to call the emperor by his preferred titles, augustus semper or semper augustus. Adrian might have been scared by the emperor's strong approach to Rome. He had been forcing cities to obey him and claiming imperial rights. If so, this might have made him overreact to what seemed like a small insult.

After the imperial coronation, both sides seemed to be extra careful to follow the Treaty of Constance. For example, Barbarossa refused to meet with representatives from the Roman commune. However, he did not defend the papacy as Adrian had hoped. He stayed in Rome only long enough to be crowned, then left immediately. This was "dubious protection" for the pope. Before he left, his army clashed violently with Rome's citizens, who were angry at what they saw as a show of imperial power in their city. Over 1,000 Romans died. The Senate continued to rebel in Rome, and William of Sicily remained strong in the pope's lands. Adrian was caught between the king and the emperor. Barbarossa's failure to suppress the Roman commune for Adrian led the pope to believe the emperor had broken the Treaty of Constance. Also, on his march north, the emperor's army looted and destroyed the town of Spoleto. Adrian also left Rome, as his relations with the commune were too fragile to guarantee his safety after the emperor left. As a result, the pope was in "virtual exile" in Viterbo, and relations between the two leaders got even worse.

Normans, Greeks, and Apulians

Because of these problems, Adrian responded positively to offers from the Byzantine Emperor Manuel I. He also welcomed the local nobles of Southern Italy. They saw Adrian's support as a chance to overthrow King William of Sicily. Adrian had recently excommunicated William for invading the pope's lands. The rebellion started well, with rebels winning battles in Bari, Trani, and Andria. They had already found a powerful ally in Emperor Manuel and welcomed anyone, including Adrian, who was against William. Their leader, Count Robert of Loritello, had been accused of treason by William but had escaped north. William was temporarily sick, which brought out his enemies. Among them, Adrian excommunicated William. By 1154, William had captured important towns in the pope's territory. In the summer of 1155, a rebellion broke out in southern Italy by the local nobles against King William. One group of rebels, with Emperor Manuel's support, took over Ancona. By winter 1155, few people thought the Sicilian monarchy would survive. According to one account, the rebels asked Adrian to come to them as their feudal lord, to be their spiritual guide, and to bless their efforts. Adrian, believing William's kingdom would soon collapse, tried to take advantage of William's weakness and allied with the rebels in September. This turned out to be a mistake. William had already asked Adrian for a peace meeting, which the pope had rejected scornfully.

Alliance with Manuel I in 1156

Emperor Manuel I had started his own military operation against William in southern Italy in 1154. He found Adrian to be a willing ally. Adrian expressed his wish "to help in bringing all the brethren into one church." He compared the Eastern Church to a lost coin, a wandering sheep, and Lazarus who had died. Adrian's isolation led him to make an agreement with the Eastern Empire in 1156. He was reacting to outside political pressures, not starting a new policy. As a result, he "became involved in a fruitless Byzantine plan to overcome the Normans." This plan ended, as often happened when popes ventured south with armies, in a Norman victory. Adrian organized a papal army made up of Roman and Campagnan nobles and crossed into Apulia in September 1155.

It has been suggested that Manuel offered to pay Adrian a large sum of money to give him certain Apulian cities. However, it seems unlikely this ever happened. Adrian was completely against the idea of a Byzantine kingdom right next to his own lands. This was true even though Manuel was not pushing his ancestors' historical claim to all of southern Italy. Manuel was mainly interested in the coastal areas. Initially, his campaign succeeded, and by 1155, he had occupied the area from Ancona to Taranto. Byzantine money allowed Adrian to temporarily restore his vassal, Robert, Count of Loritello. However, on one occasion, William managed to capture 5,000 pounds of gold from Manuel that was meant for the pope's war. There was talk of an alliance between the Roman Pope and the Eastern Emperor. Adrian sent Anselm of Havelberg to the East to arrange it, but the talks failed. Some historians argue that Adrian would not have been interested in an alliance without the lure of Byzantine gold. Although the Byzantine Emperor sent his army to support the pope in Italy, Adrian believed that the emperor's power could not be independent of the pope. Adrian was open to Manuel's idea of uniting the Eastern and Western Roman Empires, but he didn't like how the offer was made. He especially disliked Manuel's suggestion that the pope's power was only spiritual. Adrian believed that all Christians, East or West, should be under the authority of the Church of St Peter.

Norman Victory

King William's strategic position was not good. He offered Adrian large sums of money for the pope to withdraw his forces. However, most of Adrian's advisors were against negotiating with the Sicilians, and the king's offer was rejected somewhat proudly. This turned out to be a big mistake. William soon won decisive victories over both the Greek and Apulian armies in mid-1156. This ended with the final defeat of the Eastern Empire at the Battle of Brindisi. When William soundly defeated the rebels, Adrian, who was now even more stuck with the problems in Rome and without allies, had to ask for peace on the king's terms. This was another external event that Adrian couldn't control but had to deal with. He was effectively captured and forced to agree to terms at Benevento three weeks later. This one event changed Adrian's policy for good.

As a result, at the Concordat of Benevento, Adrian had to grant William the lands he claimed in southern Italy. This was symbolized by the pope giving William his own flag-decorated lances and the kiss of peace. The pope was accepted as William's feudal overlord. However, Adrian was forbidden from entering Sicily without an invitation from the king. This gave William effective authority over the church in his own land. In return, William pledged his loyalty to the pope. He also agreed to pay an annual tribute and provide military support when asked. The treaty gave extended powers to the Kings of Sicily that they would enjoy for at least the next 40 years. This included powers over church appointments that were traditionally held by the popes as the region's feudal lord. Adrian's treaty with William angered the emperor. Frederick saw it as a personal insult that Adrian had dealt with the two rivals to the Empire in Italy. This confirmed his view of Adrian's papal arrogance. This, some historians suggest, planted the seeds for the disputed election after Adrian's death.

The defeat of Manuel's army left the pope vulnerable. In June 1156, Adrian was forced to make peace with the Sicilian King. However, the terms were generous. They included loyalty and obedience, payment for recent invasions of papal lands, help against the Romans, and freedom from royal control for the Sicilian church. Adrian's new alliance with William made relations with Barbarossa worse. Frederick believed that Adrian had broken the Treaty of Constance twice by allying with both King William and the Byzantine Emperor. Relations between the pope and emperor were "irreparably damaged." Adrian probably acted as a mediator the following year to make a peace treaty between William and Manuel. The emperor tried to stop the treaty by sending his most experienced diplomat to intervene. He likely saw a Sicilian-Byzantine alliance as being directed against him.

The alliance with William had probably been strengthened by the pope's belief that Barbarossa had already broken the Treaty of Constance. At the Treaty of Benevento, Adrian was represented by three cardinals. The papacy was forced to give up much valuable land, rights, and income to William. The emperor felt personally betrayed. According to a writer of the time, the pope "wished to be an enemy of Caesar." However, some historians suggest that the imperial alliance with the papacy had only ever been for convenience. It was ready to be discarded when it had served its purpose. Others suggest that because Benevento was an imperial town, Adrian staying there for eight more months after the treaty showed he was asserting his power.

Problems with Translation in 1157

By 1157, Adrian was able to live in Rome again. He had secured the southern border with Sicily and the commune was peaceful. He was in a more secure position than any pope had been for decades. However, relations with the emperor worsened in 1157. In a letter to the emperor, Adrian used the Latin word beneficium. Some of Barbarossa's advisors translated this as "fief," which meant a piece of land held in return for service to a lord. This implied that the pope saw the Empire as being under the papacy. The emperor had to stop one of his dukes from attacking the pope's messengers.

However, some historians argue that Adrian's use of the word was harmless. He meant that he conferred the Imperial crown as a "favor" or "good deed." Historians disagree on whether the use of the word was deliberate. Some believe it was a deliberate provocation by an anti-Imperial group within the pope's court. This group wanted to justify Adrian's treaty with King William. Others say this view is "scarcely credible." Adrian was not in a strong position to threaten Frederick. He also knew the emperor was planning a campaign against Milan the next year and wouldn't want to provoke him into marching on the Papal States.

In October 1157, Barbarossa was celebrating his wedding in Besançon with an Imperial Diet, a formal assembly. Papal messengers, Cardinals Roland and Bernard, visited him. Their mission was important, bringing personal letters from Adrian. They were met "with honor and kindness," claiming to bring good news. The pope complained that no one had found out who attacked Eskil, the Archbishop of Lund, while he traveled through Imperial territory. Adrian complained that Eskil had been captured "by certain godless and infamous men" in Germany, and Frederick had done nothing to free him. Adrian's letter criticized the emperor for "dissimulation" and "negligence." It also accused Rainald of Dassel, one of the emperor's advisors, of being a "wicked counsellor." However, some describe it as a "mild rebuke." The tone was that of someone surprised and a little hurt. Adrian felt that after treating Frederick so kindly, he hadn't received a better response. But the words used caused immediate offense. Adrian's defense of Eskil further damaged his relationship with Barbarossa. Adrian's timing for rebuking the emperor was sure to offend him. Even if unintentional, the pope should have told his delegates to meet Barbarossa privately, not in public. Equally provocative, Adrian later said that letters criticizing the emperor's behavior were somehow to his advantage. Adrian's "sharp" words also made the emperor's advisors more unhappy with his messengers. The pope had also ordered that before any talks, the emperor's council must accept Adrian's letters "without any hesitation...as though proceeding from our mouth." The cardinals made things worse by calling Frederick "brother."

The emperor was also annoyed to find blank parchments with the papal seal attached when he searched the messengers' rooms. He understood this to mean that the messengers planned to present supposed direct instructions from the pope whenever they felt it was necessary. Barbarossa claimed that he held his crowns directly from God and that Adrian "did not understand his Petrine commission if he thought otherwise." After Adrian's letter was read, there was an uproar. Worse, according to Barbarossa's writer Otto of Freising, the messengers added to the insult by asking those present, "from whom does he have the empire, if not from our lord the pope?" The two churchmen were almost beaten up, but the emperor helped them escape quickly.

Explaining the Translation

In June 1158, representatives from both sides met in Augsburg. Adrian tried to calm the emperor. He claimed that he did not mean "fief" but "good deed." He wrote, "Among us beneficium means not a fief but a good deed." However, this explanation was not very convincing. On the other hand, the emperor, Frederick, could not read. He relied on others to translate everything for him. So, he was always at risk of relying on wrong translations. It is possible that this happened at Besançon. If taken literally, this phrase seemed to say that Adrian was the emperor's feudal overlord.

Some historians argue that the mistranslation was a deliberate trick by Rainald of Dassel, Barbarossa's chief official. Rainald was a "multilingual provocateur" whose office was spreading propaganda against Adrian. The pope had earlier condemned Rainald's election as Archbishop of Cologne and believed Rainald was the "Devil's agent." Rainald might have intended to cause trouble between the emperor and the pope. If so, he succeeded, as Barbarossa was barely stopped from sending an army against Adrian. The emperor did make a public statement against Adrian, calling for him to be removed from office. He claimed that Adrian, as the son of a priest, was not a proper pope. However, this argument was a "double-edged weapon." If Adrian was not a proper pope, then Frederick was not a proper emperor. This is likely why this point was not pushed further. Adrian's letter from Augsburg can be understood differently depending on how one views the original offense. If the Besançon letter was not seen as deliberately provocative, then there was no need for Adrian to withdraw from that provocation.

Adrian's choice of words might also have been a "calculated ambiguity." He never publicly said which meaning he intended. This allowed him to suggest the emperor misunderstood him, while also hinting to his own church that the emperor was indeed a papal vassal. Adrian "trivialized" Barbarossa's anger with irony. He commented that "this should not have vexed the heart of even one in lowly station, to say nothing of so great a man." The Augsburg meeting seemed to improve relations between the pope and emperor. However, the main problem remained unsolved. Any improvement was temporary. They fell out again later that year over the appointment of the next Archbishop of Ravenna. This brought up the question of their roles again, as nominations were split between their preferences. In the end, the emperor's choice was elected against Adrian's wishes. There was also growing disagreement over the traditional Imperial tax levied in northern Italy.

Imperial Claims in Northern Italy

Adrian's opposition to the appointment of Guido of Biandrate made the emperor so angry that he stopped putting the pope's name before his own in their letters. This had been a traditional sign of honor. Furthermore, he began strongly asserting his claims over Lombardy. In 1159, the Diet of Roncaglia issued a series of decrees claiming large lands in northern Italy. This caused enough concern that the cities of Milan, Brescia, Piacenza, and Crema approached Adrian for help. Milan had already been "half-destroyed" by Barbarossa, and Crema had suffered a "brutal siege." Since the lands concerned were part of the pope's territory, Adrian, who was in Bologna, rejected Barbarossa's claim. He gave him 40 days to withdraw his claims, or face excommunication, which meant being cut off from the Church. However, Adrian's involvement in a dispute between the emperor and the Lombard towns was "inevitable," but it became one of the most explosive issues of his time.

The situation facing Adrian was very serious. Accepting Frederick's claims would have meant Adrian "abandoning the whole Italian church." Adrian also had his own demands. Frederick was to stop sending envoys to Rome without papal permission. He should only be paid the Imperial tax from his Italian lands while he was in Italy. Also, papal lands in northern Italy should be returned to the church. Adrian's demands were not well received. Adrian died before his 40-day deadline expired. As relations between the emperor and pope worsened, Barbarossa began putting his own name before Adrian's in their letters. He also addressed the pope using the singular "you," which was a sign of disrespect. By this time, the emperor viewed Adrian with contempt.

Relations with England

Pope Adrian "was not unmindful of the interests and well-being of his English homeland." His time as pope was when English influence was strongest in the papal court. Adrian remained loyal to the worship of St Alban and often supported King Henry's political goals when he could. For example, John of Salisbury, after spending a long time with Adrian, seemed to believe he would become a cardinal. However, John fell out with King Henry for an unknown reason. Adrian, who wanted to help his friend but was also a diplomat, could not afford to anger his only major supporter in northern Europe. Adrian also welcomed at least two official visits from St Albans in 1156 and 1157. In 1156, Adrian ordered King Henry II to appoint an unknown person named Hugh to a church position in London. Two months after Adrian's election, he wrote to Roger, Archbishop of York, confirming the papal legates in their roles.

Adrian had been away from England since 1120. It should not be assumed that he automatically felt affection for the country that had given him "no reasons to cherish warm feelings." However, in 1156, when John of Salisbury fell out of favor with the English King, Adrian regularly asked Henry to reinstate his friend. This was eventually achieved, but it took a year. Anglo-Papal relations at this time were marked by "persistent intervention" from the pope and a degree of acceptance from the English Church. However, Adrian was willing to get involved in English church affairs when it suited him. For example, in February 1156, he threatened Nigel, Bishop of Ely, with suspension from office. This was because Nigel had "stripped-down, sold, or used as security, a quite astounding number of Ely's monastic treasures."

Among other favors, he confirmed the nuns of St Mary's Priory in Neasham in possession of their church. He also gave St Albans Abbey "a large dossier of privileges and directives." These exempted it from the authority of its bishop, Robert de Chesney. He also confirmed that the Archbishop of York had authority over Scottish bishops and was independent from the Archbishop of Canterbury. He also granted papal protection to Scottish towns, like Kelso, in 1155. On occasion, he sent his young students to King Henry's court to learn aristocratic skills like hunting, falconry, and martial arts.

Adrian had a "special relationship" with his "home abbey" of St Albans. This was shown in his very generous and wide-ranging privilege called Incomprehensibilis, issued in Benevento on February 5, 1156. With this grant, Adrian allowed the abbot the right to wear special robes, effectively removing the abbot from the bishop's authority. The monks were also allowed to elect their abbot without needing the bishop's approval. They could not be forced by the bishop to allow him or his agents into the abbey, or to attend bishop's meetings. In two follow-up letters, Adrian gave the Abbot of St Albans authority to replace clerks in churches under his control with his preferred candidates. Adrian "rained privilege after privilege upon the abbey."

The Laudabiliter Bull

Perhaps Adrian's "most striking" gift to England was the Papal Bull Laudabiliter from 1155. This was supposedly issued while Adrian was in Benevento or had moved to Florento. John of Salisbury later claimed credit for it. He wrote that "at my request [Adrian] conceded and gave Ireland as a hereditary possession to the illustrious king of the English, Henry II." This document granted the island of Ireland to Henry II as his property. Adrian's reason was that, ever since the Donation of Constantine, a forged document that claimed the pope had authority over Western Europe, the pope had the right to distribute Christian countries as he wished.

The Bull "granted and gave Ireland to King Henry II to hold by hereditary right, as his letters witness unto this day." It was also accompanied by a gold papal ring "as a token of investiture," meaning a symbol of the transfer of power.

Actions as Pope

In 1155, the city of Genoa asked Adrian for help to protect their trading rights in the East. The same year, Adrian issued a decree called Dignum est. This allowed serfs, who were like servants tied to the land, to marry without needing their lord's permission, which had been the tradition. Adrian's reasoning was that a sacrament, like marriage, was more important than a feudal duty. He believed no Christian had the right to stop another from receiving a sacrament. This became the final statement defining marriage as a sacrament. It remained so until church law was rewritten in 1917. The same year, Adrian consecrated Enrico Dandolo as the Primate of Dalmatia. Two years later, Adrian granted him authority over all Venetian churches in the Eastern Empire. This was a remarkable move. It was the first time one church leader was given authority over another, creating a Western equivalent of an Eastern Patriarch. He also confirmed the punishment of Baume Abbey for not obeying a papal messenger.

Adrian confirmed the special rights of the Knights Templar and recorded them in a book called the Liber Censuum. He also enforced rules against unfair church elections and condemned church officials who used physical force against the church. Perhaps remembering his own past, he also issued several official documents favoring the Augustinian canons. Again, he focused on religious houses he had personal connections with. St Ruf, for example, received at least 10 special documents. In one of these, he expressed a "special bond of affection" for his old abbey, which he said had been like a mother to him.

Adrian argued that in the difficult succession to Alfonso I of Aragon, even though Alfonso had legally named his brother as heir, his brother was not a direct heir because Alfonso had no son. This was the background for a planned crusade into Spain, suggested by the Kings of England and France, which Adrian rejected. However, he welcomed their new friendship.

It was probably Adrian who made Sigfrid of Sweden a saint around 1158, making Sigfrid Sweden's "apostle." Adrian's interest in Scandinavia continued during his time as pope. He especially worked to create a main church center in Sweden. He was also keen to protect its church from interference by ordinary people. In January 1157, Archbishop Eskil personally asked Adrian in Rome for protection from King Swein of Denmark. Adrian appointed the Bishop of Lund as his representative in the region and recognized him as the main church leader over both Sweden and Denmark.

Other cardinals Adrian appointed included Alberto di Morra in 1156. Di Morra, also a canon regular like Adrian, later became Pope Gregory VIII in 1187. Boso, who was already the pope's financial manager since 1154, was appointed to a higher role the same year. Adrian also promoted Walter to his own Cardinal Bishopric of Albano. Walter is thought to have been English, possibly also from St Ruf, but little is known about his career. In contrast, his appointment of Raymond des Arénes in 1158 was a well-known lawyer with an established career under Adrian's predecessors. These were all good additions to the pope's staff. They were experienced, educated, and skilled in administration and diplomacy, which shows Adrian's wisdom in choosing them. He may have received the hermit and later saint Silvester of Troina, whose only recorded journey was from Sicily to Rome during Adrian's time as pope.

Adrian continued to reform the pope's finances, which had started under his predecessor, to increase income. However, he often had to ask for large loans from important noble families. His appointment of Boso as the pope's financial manager greatly improved the pope's finances by making the system more efficient. However, he also recognized the cost of defending the papacy, saying "no-one can make war without pay." Adrian also strengthened the pope's position as the feudal lord of the regional nobles. His success in this has been described as "never less than impressive." In 1157, for example, Adrian made Oddone Frangipane donate his castle to him. Adrian then granted it back to Oddone as a fief. Sometimes Adrian simply bought castles and lordships for the papacy, as he did with Corchiano. Adrian received personal oaths of loyalty from a number of nobles north of Rome, making them direct vassals of St Peter. In 1158, for example, Ramon Berenguer, Count of Barcelona, was accepted "under St Peter's and our protection" for fighting in the Reconquista against the Saracens. In 1159, Adrian approved an agreement with the leaders of Ostia, a semi-independent town. They agreed to pay the pope an annual feudal rent for his lordship. Adrian's vassals, and their families and vassals, took oaths of loyalty to the pope. This meant the vassal's own vassals were now directly loyal to the papacy. One of Adrian's greatest achievements, according to Boso, was acquiring Orvieto as a papal fief. This city had "for a very long time withdrawn itself from the jurisdiction of St Peter." Adrian, in 1156, was the first pope to enter Orvieto and have any temporal power there.

Adrian seems to have supported crusades since his time as abbot of St Ruf. As pope, he was equally keen to restart the crusading spirit among Christian rulers. The most recent crusade had ended badly in 1150. But Adrian made a "novel approach" to launching a new one. In 1157, he announced that indulgences, which were special spiritual benefits, would now be available not only to those who fought in the East, but also to those who supported the war effort without campaigning abroad. This meant people who gave money, men, or supplies could also receive the benefits of crusading. However, his proposal did not get much interest, and no further crusading took place until 1189. He did not approve of crusading within Christendom itself. When the French and English kings proposed a crusade into Muslim Spain, he urged them to be careful. In his letter of January 1159, he advised that "it would seem to be neither wise nor safe to enter a foreign land without first seeking the advice of the princes and people of the area." Adrian reminded Henry and Louis of the bad consequences of poorly planned crusades, referring to the Second Crusade, which Louis had led. He reminded him that Louis had invaded "without consulting the people of the area."

Adrian also started building projects throughout Rome and the papal lands. However, because his time as pope was short, not much of his work is still visible today. The work included restoring public buildings and spaces, and improving the city's defenses. One writer reported how, for example, "in the church of St Peter [Adrian] richly restored the roof of St. Processo which he found collapsed." In the Lateran, he "caused to be made a very necessary and extremely large cistern." Because he traveled a lot during his time as pope, he also built many summer palaces across the papal lands, including in Segni, Ferentino, Alatri, Anagni, and Rieti. Much of this fortification and building work, especially near Rome, was to protect pilgrims. Adrian was responsible for their safety both spiritually and physically.

Although his time as pope was relatively short, lasting four years, six months, and 28 days, he spent nearly half that time outside of Rome. He was either in Benevento or traveling around the Papal States. Especially in the early years of his reign, his travels reflected the political situation. He made "short bursts" of travel as he tried to meet or avoid the emperor or William of Sicily, depending on what the situation required.

Pope Adrian's Beliefs and Views

Pope Adrian was aware of the huge responsibilities of his office. He told John of Salisbury that his papal crown felt "splendid because it burned with fire." He also deeply respected the history of the Petrine tradition, which refers to the authority passed down from St Peter. More than many popes before him, Adrian upheld the "unifying and co-ordinating role of the Papal office." He often said he saw his position as being like a steward, someone who manages things for others. He also recognized his own smallness within that tradition. He told John of Salisbury that "the Lord has long since placed me between the hammer and the anvil, and now he must support the burden he has placed upon me, for I cannot carry it." This explains why he used the title Servus servorum Dei, which means "Servant of the Servants of God." This title combined his ideas of "stewardship, duty and usefulness" in three words.

Adrian was keen to emphasize that the Western Church was superior to the Eastern Church. He took every chance to tell members of the Eastern Church this. Adrian described his approach to relations with his political rivals in a letter to the Archbishop of Thessaloniki. He argued that St Peter's authority could not be divided or shared with earthly rulers. As the descendant of St Peter, he believed his authority should also not be shared. Central to Adrian's view of his papacy was the belief that his court was the highest court in Christendom. It was the final court of appeal, and he encouraged appeals from many countries. In an early letter, defending the idea of the pope as a monarch, he compared Christendom to the human body. All parts can only work properly if they have a main guide and helper. To Adrian, Christian Europe was the body, and the pope was the head. One historian has suggested that Adrian firmly believed in "enlarging the borders of the Church, setting bounds to the progress of wickedness, reforming evil manners, planting virtue, and increasing the Christian religion." Adrian wanted to know what people thought of the Roman Church, and he often asked John of Salisbury. John also recorded Adrian's views on the papacy accepting gifts from Christians. Some people thought this was like simony, which is buying or selling church offices, and a sign of corruption. Adrian, John reported, replied by referring to the fable of the belly. This fable explains that the church has the right to receive and distribute resources to the Christian body based on merit and usefulness.

Adrian was a man of action who didn't like long theoretical discussions. However, he could also be hesitant. For example, after his big policy change at Benevento, he might not have fully understood how significant his actions were. He certainly didn't fully use the new policy. Adrian was a skilled administrator who used capable agents. He was also a traditionalist. He strongly followed Pope Gregory VII's ideas and believed it was his duty to not only believe in those ideals but to enforce them. He also believed in the need for reform, as shown by his clarification of the marriage sacrament and his enforcement of free elections for bishops.

Writings

A 16th-century writer, Augustino Oldoini, said that Adrian had written several works before he became pope. These included a book about the Conception of the Blessed Virgin, a detailed report about his diplomatic mission, and a catechism, or religious instruction book, for the Scandinavian church. Some of his letters still exist. One letter, from Hildegard, urged him to crush the Roman commune. Editors of Hildegard's letters note that this was "perhaps unneeded," as Adrian placed the city under Interdict almost immediately. Many of Adrian's letters with Archbishop Theobald and John of Salisbury have also been published in collections of John's letters.

Adrian's official record book is now lost, but some of his formal rulings, called decretals, still exist. These covered questions like whether a priest could return to his office after causing the death of an apprentice, the payment of tithes (church taxes), and the marriage of unfree people. Adrian's ideas on tithe payment also became part of Church Law. They were recognized by people at the time as very important and were included in collections of church law being put together then.

Personality

Adrian's character seems to have been a mix of different traits. Some historians see him as tough and unyielding, while others see him as a relatively mild man who could be influenced by those around him. However, he was not a puppet to be controlled by cardinals, nor was he overly dramatic. Instead, he was a disciplined man who followed existing rules and routines. He was a practical man who responded carefully to problems brought before him.

Adrian's financial manager, Boso, who later wrote about Adrian's life, described the pope as "mild and kindly in bearing, of high character and learning, famous as a preacher, and renowned for his fine voice." He was also described as eloquent, capable, and having "outstanding good looks." Some believed Adrian was "as firm and as unyielding as the granite of his tomb." However, others suggest that, at least after the Treaty of Benevento, he must have been more open to change. Some wonder if he deliberately used these traits to advance his career. Boso's description might mean that Adrian was good at making friends and influencing powerful people through charm. Similar traits can be seen in the accounts from John of Salisbury, who was a close friend of the pope.

Adrian's own view of his office is summed up in his words: his "pallium was full of thorns and the burnished mitre seared his head." He supposedly would have preferred the simple life of a canon at St Ruf. However, he also respected those who worked under him in the church's administration. He once said that "we ought to reward such persons with ecclesiastical benefices when we conveniently can." This approach is reflected in his promotion of other Englishmen, like Walter, and possibly John of Salisbury, to high office. Adrian "had not forgot his origins; he liked to have Englishmen about him."

His increasing control over Rome and the papal lands shows that he was an effective organizer and administrator. Adrian's strength of personality can be seen in his election itself. Despite being an outsider, a newcomer, and lacking support from an Italian noble family, he reached the highest position in his church. These qualities made him independent.

His biographer, Cardinal Boso, was a close friend who visited Adrian in Rome. John of Salisbury's feelings for Adrian were so strong that they have been compared to the strong bonds between kings.

Modern historians have not always praised Adrian. Some argue that Adrian used shameful arguments in his dispute with Barbarossa. Others have called Adrian "petulant" and criticized his "sarcastic" manner towards Barbarossa.

Death

By the autumn of 1159, it might have been clear to Adrian's household that he did not have long to live. This might have been partly caused by the stresses of his time as pope, which, though short, was difficult. Pope Adrian died in Anagni, where he had gone for safety from the emperor, from a severe throat infection on September 1, 1159. He died "as many Popes had died before him, an embittered exile; and when death came to him, he welcomed it as a friend." He was buried three days later in a simple 3rd-century stone coffin that he chose himself. In 1607, an Italian archaeologist opened Adrian's tomb. He described the body, which was still well preserved, as that of an "undersized man, wearing Turkish slippers on his feet and, on his hand, a ring with a large emerald," and dressed in a dark robe.

At the time of Adrian's death, the emperor's pressure on the papacy was stronger than it had been in a long time. It is not surprising that the cardinals could not agree on his successor. It is likely that in the months before his death, the cardinals knew a split was likely to happen soon. Some historians suggest that Adrian's own policies made a split in the College of Cardinals almost certain, regardless of the emperor's influence. Others argue that the different beliefs of individual cardinals were causing divisions in the pope's court in Adrian's last months. However, some believe Frederick Barbarossa himself caused the split.

In September 1159, Adrian had agreed to excommunicate Barbarossa, but he did not swear to it. He also did not have time to decide on the request of Scottish messengers who had been in Rome that summer. They wanted the Diocese of St Andrews to become a main church center and for Waltheof of Melrose to be made a saint. One of his final acts was blessing his preferred successor, Bernard, Cardinal-Bishop of Porto. This could have been Adrian's "masterstroke." The election of Bernard, as a candidate acceptable to the emperor, might have prevented the future split. The fact that the cardinals eventually agreed with Adrian's choice shows he had chosen wisely.

Pope Adrian was buried in St Peter's on September 4, 1159. Three imperial ambassadors who had been with the pope when he died were present. They were Otto of Wittelsbach, Guido of Biandrate, and Heribert of Aachen. However, as soon as the emperor heard of the pope's death, he "sent a group of agents and a great deal of money to Rome" to try to ensure a successor with pro-Imperial sympathies was elected.

Events After Adrian's Death

The meeting between Adrian and the city envoys in June 1159 might have discussed the next papal election. Adrian was known to have been with 13 cardinals who supported his pro-Sicilian policy. Cardinal Roland's election to succeed Adrian led to both the conflict with the Empire getting worse and the alliance with William of Sicily becoming stronger. The split in the Church affected papal policy in Italy, making the pope a passive observer of events in his own region. A disputed election was an inevitable result whenever the pope and emperor had a falling out. Relations between Barbarossa and Manuel, which were already poor, ended completely after Manuel's German wife died earlier in 1159.

After Adrian's death, the Church faced "another long and bitter schism," or split. Tensions between different groups led to two popes being elected, with "mutually unacceptable candidates." This led to "disgraceful scenes" in Rome. But since neither side was powerful enough to defeat the other, each appealed to the European powers for support.

Although the pope's forces were not enough to defeat Barbarossa completely, the war in Lombardy gradually turned against the emperor. After the Kings of France and England recognized the pope, the military situation became more balanced. However, peace was not established between the Papacy, the Empire, Sicily, and the Byzantine Emperor until Barbarossa was defeated at the Battle of Legnano in 1176 and the Treaty of Venice the following year. The split continued until the election of Pope Alexander III in 1180. During this time, the emperor's officials spread a series of fake letters, some supposedly written by Adrian, to support the imperial candidate. One such letter, supposedly to Archbishop Hillin of Trier, contained a deliberately wrong rewriting of Charlemagne's assumption of the imperial title. In it, Adrian supposedly condemned the German kings who owed everything to the papacy yet refused to understand that. This letter was clearly meant to anger its imperial audience. Another letter, from the emperor to an archbishop, called Adrian's church "a sea of snakes," a "den of thieves and a house of demons," and Adrian himself as "he who claims to be the Vicar of Peter, but is not." Adrian, in turn, supposedly called the emperor "out of his mind." These letters are interesting because they show what Barbarossa believed were the most important arguments between him and Adrian.

Further away, war was threatening between England and France. Lands lost by Adrian to Sicily at the Treaty of Benevento were eventually regained by Pope Innocent III early in the next century. By then, the Kingdom of Sicily had merged with the Empire. Innocent saw Adrian's original grant as taking away from the privilege of the Apostolic See, and he made strong and successful efforts to remove the Empire from southern Italy.

The 1159 Papal Election

The 1159 papal election was disputed. The College of Cardinals split into two groups: the "Sicilian" group, who wanted to continue Adrian's pro-William policy, and the "Imperial" group. The Sicilian group supported Cardinal Roland. The Imperial group supported Ottaviano de Monticelli. Roland was elected Pope Alexander III. His opponents did not accept the result and elected another pope, Victor IV. The Imperial party disagreed with the new friendly policy towards Sicily and favored the traditional alliance with the Empire. A letter from the Imperial group of electors claimed that Adrian was a "dupe" of the Sicilian faction within the cardinals. The emperor's willingness to serve Victor, for example by holding the Antipope's horse and kissing his feet, showed his attitude towards his candidate. The election to choose Adrian's successor was a "riotous and undignified spectacle." Alexander was elected by two-thirds of the cardinals, while Victor's support dropped from nine to five cardinals. Two more antipopes were elected before Alexander's death in 1181, when a unity candidate was found. Alexander inherited a difficult situation from Adrian, who had created a powerful enemy for the papacy in the emperor. However, Alexander managed to navigate through many crises and held his own. Within a year, Emperor Manuel recognized Alexander, as did the English King Henry, although Henry waited nine months to do so. Although Octavian received less support from the cardinals, he had the support of the Roman commune. As a result, Alexander and his supporters were forced into the safety of the Leonine Borgho, a walled area.

Legacy and Impact

In the 1300s, Adrian was recorded in St Albans' Book of Benefactors. This "ensured that the memory of the English Pope would remain forever." A 19th-century bishop described Adrian IV as "a great pope; that is a great constructive pope, not a controversial one." Some historians say Adrian's time as pope is often remembered only for him being the only English pope or as a small detail in Anglo-Irish history. However, because he lived in many different countries over the years, he shows how connected 12th-century religion was across Europe.

Adrian's time as pope was important because he was the first pope to face the "newly released forces" of the recently crowned King Henry and Emperor Frederick. On the other hand, by rejecting the request of Kings Louis and Henry to crusade in Spain, Adrian likely prevented the secular powers from embarrassing themselves. It's possible Adrian saved the Iberian Peninsula from a disaster like the Second Crusade to the East.

Some historians argue that while Adrian "did more than any of his predecessors to secure the papal position in central Italy," he was "much less successful in his conduct of relations with the empire." Others agree that Adrian was "the greatest pope since Urban II," but that he stood out because the popes before him were not as strong. He is also overshadowed by his powerful successor. However, Adrian played a key role in guiding the papacy through a very critical phase of its long history.

Adrian has been described as "diplomatically very well versed and experienced, dispassionate and purposeful in his government." Adrian, "the pope of action," made papal theory very practical. However, he was not a dictator. Adrian's new approach to gaining support for a crusade in 1157 became "a pivotal feature of crusading from the reign of Innocent III onwards." Innocent III himself recognized how much he owed to Adrian's time as pope. Innocent made Adrian's changes to the Imperial coronation official procedure. Even the Besançon affair, where he stood firm against the emperor, makes him look strong compared to the noisy Germans.

The period just before Adrian became pope was one where "even without a direct imperial threat, Roman feuds, Norman ambitions and incompetently led crusades could reduce grandiose papal plans to ashes." The papacy itself was in a constant struggle. However, historians disagree on how much the papacy was to blame for this. It's important to recognize how vulnerable the papacy was. Adrian's policy, if he had one, was shaped by events rather than him shaping them. There was a perfect match between Adrian's symbolic actions and his government actions. Adrian and his pro-Sicilian cardinals were blamed in 1159 for the conflict that followed.

Adrian IV is described as a "true son of the reforming papacy." However, the papal reform movement did not seem to believe that Adrian would carry out its program. Leading reformers of the day sought church renewal in other ways. Adrian is credited with starting the process by which the popes expanded their own lands. Adrian brought Rome back under strong papal control with considerable success. He also expanded the pope's property around the city, especially in northern Lazio.

Although his time as pope was shorter than others, he acquired more castles and lordships within papal control than either of them. He did this in a more difficult political situation. He was also a tougher pope than his two immediate predecessors. His papacy was "extremely formative," and his policy of reform was continued by reforming popes of the 1200s. However, his papacy was "fraught with political intrigue and conflict." Adrian has been described as having "theocratic pretensions," meaning he believed in the pope's supreme authority. It was also during his time as pope that the term "Vicar of Christ" became a common way to refer to the pope.

Adrian left a high reputation after his death. He became "something of a role model for later popes." Some historians suggest that the blame for the poor relations between Adrian and Frederick can be placed on their advisors, who focused on principles rather than compromise. Although England did not provide any more popes, relations between England and the papacy remained strong after Adrian's death and into the 1200s. Adrian's generous treatment of St Albans also had consequences. He had granted it such broad and grand privileges, which were confirmed by his successors, that they caused anger and jealousy in the English church.

Adrian is seen as the one who began restoring the Papal monarchy, which would reach its peak under Innocent III. Only Innocent, the great Roman, realized the value to the papacy of following where Adrian, the unique Englishman, had led.

Nicholas Breakspear School in St Albans, England, built in 1963, is named in his honor.

See also

In Spanish: Adriano IV para niños

In Spanish: Adriano IV para niños

- List of popes

- Cardinals created by Adrian IV