Battle of Legnano facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Legnano |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Guelphs and Ghibellines | |||||||

The defense of the Carroccio during the battle of Legnano (by Amos Cassioli, 1860) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Papal States | Holy Roman Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Pope Alexander III | Frederick I Barbarossa | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 12,000 | 3,000 (incl. 2,500 knights) |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| heavy | heavy | ||||||

The Battle of Legnano was a very important fight that happened on May 29, 1176. It was fought near the town of Legnano in Lombardy, Italy. On one side was the army of Frederick Barbarossa, who was the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. On the other side were the soldiers of the Lombard League, a group of cities in Northern Italy.

Even though both sides knew the other was nearby, they met by surprise. This meant they didn't have time to plan their battle moves.

This battle was a big moment in a long war. Emperor Frederick Barbarossa wanted to control the cities of Northern Italy. But these cities decided to stop fighting each other and team up. They formed the Lombard League, which was supported by Pope Alexander III.

The Battle of Legnano was the last time Emperor Frederick Barbarossa came to Italy with his army. After losing, he decided to try talking instead of fighting. This led to the Peace of Constance in 1183. In this agreement, the Emperor finally recognized the Lombard League. He also gave the cities more freedom to govern themselves. This officially ended his attempts to rule Northern Italy.

The battle is even mentioned in Italy's national anthem, Canto degli Italiani. It says: "From the Alps to Sicily, Legnano is everywhere." This remembers the victory of Italian people over foreign rulers. Legnano is special because it's the only city besides Rome mentioned in the anthem. Every year since 1935, Legnano holds the Palio di Legnano to remember the battle. May 29th is also a regional holiday in Lombardy.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

A Long-Running Conflict

The fight between the cities of Northern Italy and the Emperor started a long time ago. It was part of a bigger argument called the "struggle for investitures." This was a conflict between the Papacy (the Pope) and the Holy Roman Empire over who had the right to appoint important church leaders like bishops. People who supported the Pope were called "Guelphs" and those who supported the Emperor were called "Ghibellines".

But it wasn't just about church leaders. Cities in Northern Italy were growing rich and powerful. They wanted to be free from the Emperor's rule. The Italian lands of the Holy Roman Empire were very different from the German ones. People in Italy didn't like being ruled by a German emperor.

Because of these problems, cities in Northern Italy started to govern themselves. They created a new system called the "medieval commune". This meant citizens elected their own leaders, called consuls, to handle city matters. This happened when bishops were busy with the Pope-Emperor conflict. Citizens became more involved in their city's public life and wanted to manage things themselves.

Earlier emperors didn't pay much attention to Northern Italy. This allowed cities to grow and even fight each other to become more powerful. For example, Milan conquered nearby cities like Lodi and Como.

But Frederick Barbarossa was different. He wanted to bring Northern Italy back under his control. Some cities even asked him to step in and stop Milan from becoming too strong.

Relations got even worse because of harsh actions by the Emperor. In 1160, Frederick destroyed farms and crops around Milan to cut off supplies. He ruined areas like Legnano and Rho. After Milan surrendered in 1162, the Emperor's officials made farmers pay very heavy taxes. This made the people even more against imperial rule.

Frederick's First Journeys to Italy

Frederick Barbarossa crossed the Alps five times with his army to try and control Northern Italy.

- First Journey (1154): He came with a small army and attacked some rebellious cities. He didn't attack Milan because he didn't have enough soldiers. He then held a meeting where he said the Emperor was in charge again. He was crowned Emperor in Rome in 1155. But he had a bloody fight with the people of Rome, which started problems between the Empire and the Pope. Frederick showed he wanted to fully control Northern Italy.

- Second Journey (1158): Milan and its allies were still rebellious. Frederick attacked Milan, which surrendered to avoid a long fight. Milan lost its conquered lands. Frederick held another meeting where he said all taxes should go to the Emperor. This made the Italian cities rebel again. After getting more soldiers, Frederick attacked Milan again in 1162 and completely destroyed it. He put his own officials in charge of rebel cities, taking away their self-rule. Meanwhile, the new Pope, Pope Alexander III, supported the Italian cities and was against the Emperor.

- Third Journey (1163): Some cities in northeastern Italy rebelled, forcing Frederick to come back. But his army was too small, so he couldn't win a clear victory. He returned to Germany.

The Lombard League Forms

- Fourth Journey (1166): Frederick came to Italy again with a strong army. This time, his main goal was to deal with the Pope. He supported a different Pope, but a sickness (maybe malaria) spread through his army. This forced him to leave Rome and go back north for more soldiers.

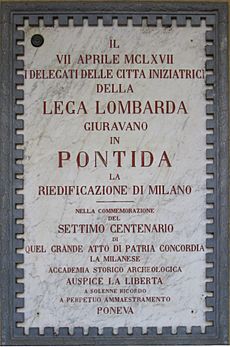

A few months before this sickness, many cities in Northern Italy had joined forces. They formed the Lombard League, a military alliance. It's traditionally said they made an oath in Pontida on April 7, 1167. However, historians aren't sure about this exact event, as it's not mentioned in writings from that time. The Lombard League grew even bigger in December 1167. Frederick tried to fight them but couldn't win, so he went back to Germany in 1168.

After Frederick left, the League founded a new city called Alessandria, named after Pope Alexander III. This was a big challenge to the Emperor's power, as they built a city without his permission. Frederick Barbarossa decided he needed to solve the Italian problem once and for all.

Frederick's Last Journey

In 1174, Frederick Barbarossa came to Italy for the fifth and final time with a large army of about 10,000 men. He tried to capture Alessandria but failed. His army was tired, so he went to Pavia, an allied city, to try and make a peace deal with the Lombard League.

During these talks, Frederick thought a deal was close. So, he sent most of his army away. But the talks failed in May 1175, and both sides got ready for war again. Frederick realized his mistake. He asked his cousin, Henry the Lion, and other leaders for more soldiers. He got some, but fewer than he hoped for.

Despite not having enough soldiers, the Emperor decided to march from Como to Pavia. This was through enemy land, but there were thick forests that offered some safety. He wanted to meet his other troops and fight the League's army. He thought a fast march would stop the League from catching him.

However, the Lombard League decided to fight the Emperor's army as soon as possible. They wanted to stop Frederick's armies from joining up. The League had about 15,000 men, but not all their forces had arrived yet. The League's military operations were led by Guido da Landriano from Milan, an experienced knight.

The Battle Unfolds

Frederick at Cairate

On the night of May 28-29, 1176, Frederick Barbarossa and his troops stopped at a monastery in Cairate. This stop caused a delay that turned out to be a big mistake. The Emperor likely spent the night in Castelseprio, a place whose rulers were enemies of Milan. Frederick wanted to cross the Olona River and reach Pavia, which was about 50 km away.

Most historians believe the Emperor's army at Cairate had about 3,000 men. Most of these were heavy cavalry (knights on horseback). Even though they were fewer in number, they were professional soldiers. The League's army, on the other hand, was mostly made up of ordinary citizens and farmers who were called to fight when needed. The League's knights were from rich families, as horses and armor were very expensive.

The Carroccio at Legnano

The leaders of the Lombard League didn't know Frederick was so close. They thought he was still far away. So, they moved their special battle wagon, the Carroccio, from Milan to Legnano. The Carroccio was a symbol of the cities' freedom and carried a cross. It was guarded by a few hundred men.

In Legnano, the Carroccio was placed on a slope near the Olona River. This was meant to give it a natural defense. The League thought Frederick would attack from one side, but he came from the opposite direction. This meant the League's escape route was blocked by the river. Another reason for placing the Carroccio in Legnano was to stop Frederick from joining forces with allies in the Seprio region.

The main part of the Lombard League army, about 15,000 men (3,000 knights and 12,000 foot soldiers), followed behind. Legnano was a good place to defend because it controlled a valley that led to Milan. There was also an important Roman road there.

Legnano also had an old castle, the Cotta castle, which was used as a military outpost. This castle, along with walls and a moat, made Legnano a fortified town. The people of Legnano were also friendly to the League's troops because Frederick Barbarossa had destroyed their lands a few years earlier. So, Legnano was a good strategic spot to stop the Emperor from attacking Milan or reaching Pavia.

First Clash at Borsano

After his stop in Cairate, Frederick Barbarossa continued his march towards the Ticino River. Meanwhile, about 700 knights from the Lombard League, who were ahead of the main army, were scouting the area.

About 4.5 km from Legnano, near Cascina Brughetto, these 700 League knights met 300 imperial knights. These were just the front-line soldiers of Frederick's army. Since the League knights were more in number, they attacked first and seemed to be winning.

But then, Frederick Barbarossa arrived with the main part of his army and charged the League's troops. Some people say Frederick's advisors told him to wait, but he wanted to attack right away. The battle turned, and the imperial troops forced the League's knights to retreat towards Milan.

This left the soldiers defending the Carroccio in Legnano alone. Frederick decided to attack the Carroccio with his cavalry, thinking the foot soldiers defending it would be easy to defeat.

Defending the Carroccio

What happened next was unusual for the time. The League's foot soldiers, with the few remaining knights, stood firm around the Carroccio. They formed defensive lines in a wide semicircle. Soldiers held up their shields, and long spears pointed out between them. The first row of soldiers even fought on their knees, creating a wall of spears.

The fight lasted for eight to nine hours. The imperial army charged many times, but the League's soldiers held strong. The first few lines of defense might have given way, but the last line held firm.

Meanwhile, the League's knights who had retreated towards Milan met the rest of the Lombard League army. The reunited army then moved back towards Legnano. They attacked Frederick's tired imperial troops from the sides and from behind. With the cavalry's return, the foot soldiers around the Carroccio also started to push back.

Frederick Barbarossa, known for his bravery, rode into the thick of the fight to encourage his men. But it didn't help. His horse was badly wounded, and the Emperor disappeared from sight. The imperial army's flag-bearer was also killed. Attacked from two sides, the imperial soldiers lost heart and began to lose badly.

The imperial army tried to escape towards the Ticino River. But the League's troops chased them for about 13 km. Many imperial soldiers were captured or killed, especially at the river. Frederick himself barely escaped and managed to reach Pavia.

After the battle, the Milanese wrote to their allies, saying they had captured a lot of gold, silver, the Emperor's banner, shield, and spear. They also took many prisoners, including important princes and nobles.

Losses

We don't have exact numbers for how many soldiers died on each side. But it's clear that the imperial army suffered heavy losses. The Lombard League, on the other hand, had fewer casualties.

Some historians believe that many of the dead from the Battle of Legnano were buried near a small, old church called San Giorgio in Legnano.

Where the Battle Happened

It's hard to know the exact spots where the fighting happened. This is because the old writings from that time are very short and sometimes mix up place names.

Most Milanese writings from the time say the battle was fought "at Legnano" or "between Legnano and the Ticino River." Other sources from the League also say "at Legnano." Imperial writings don't usually name the exact places.

Later writings, about a century after the battle, say it happened "between Borsano and Legnano."

The first part of the battle, where the two armies first met, seems to have happened between Borsano and Busto Arsizio. This is supported by an old document that says the Milanese met the Emperor's forces "between Borsano and Busto Arsizio."

For the final part of the battle, where the Carroccio was defended, one important old writing says it was "15 miles from the city" (Milan). This is about 22 km, which is the exact distance between Legnano and Milan. This writing also mentions the first clash was about 4.5 km from Legnano, fitting the Borsano/Busto Arsizio area.

One old writing says the Lombard League placed their army "inside a large pit" to prevent anyone from escaping. This suggests the Carroccio was on the edge of a steep slope near the Olona River. This way, the Emperor's cavalry would have to attack uphill. This could mean the main fight happened in the San Martino area of Legnano, near the old church of San Martino, which is on a slope. Or it could be in the Costa San Giorgio area, where there's still a steep slope today.

A popular story says that Frederick Barbarossa escaped through a secret tunnel from San Giorgio su Legnano to the Visconti castle in Legnano. In recent times, parts of very old tunnels have been found in both areas, but they were blocked for safety.

What Happened After

The Battle of Legnano ended Frederick Barbarossa's attempts to control the cities of Northern Italy by force. He also lost the support of German princes, who weren't willing to send more soldiers. Without military help, Frederick decided to try diplomacy.

This led to the Treaty of Venice in 1177. In this agreement, the Emperor recognized Pope Alexander III as the true Pope. This ended a split in the church that had lasted for years. Frederick's wife, Beatrice, also stopped being called "Empress" because her crowning was done by the wrong Pope.

The final peace talks happened in Piacenza in 1183. The Lombard League demanded full freedom for their cities, including the right to build walls, be free from most taxes, and have no interference from the Emperor. Frederick Barbarossa was against these demands at first. Before these talks, Alessandria, the city founded by the League, agreed to join the Empire.

The talks led to the signing of the Peace of Constance on June 25, 1183. This treaty officially recognized the Lombard League. Frederick gave the cities a lot of freedom in how they managed their lands, courts, and armies. They could recruit soldiers and build defenses. Imperial officials would only get involved in big court cases. The Emperor also confirmed the local laws the cities had won over years of fighting. He officially allowed cities to have their own elected leaders, called consuls, who would swear loyalty to the Emperor.

In return, the Lombard League cities formally recognized the Emperor's authority. They agreed to pay some taxes, but not the main royal taxes. They also agreed to pay the Empire a one-time payment and a yearly sum. Not only the Italian cities, but also the Pope, gained from this defeat of Frederick Barbarossa. The Peace of Constance was very important because it was the only time an Emperor officially recognized the freedoms of Italian cities. It was celebrated for centuries.

Alberto da Giussano and the Company of Death

The name Alberto da Giussano first appeared in a historical story written about 150 years after the Battle of Legnano. This story was by a monk named Galvano Fiamma in the 1300s. Alberto da Giussano was described as a brave knight who, along with his brothers, fought well in the battle.

According to Galvano Fiamma, Alberto led a group of 900 young knights called the Company of Death. This group got its name because its members swore to fight until their last breath. Fiamma said the Company of Death bravely defended the Carroccio and then charged the imperial army at the end of the battle.

However, writings from the time of the Battle of Legnano do not mention Alberto da Giussano or the Company of Death. Historians believe that Galvano Fiamma's stories might not be entirely accurate and include some legendary parts.

Images for kids

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |