Wolverhampton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Wolverhampton

|

||

|---|---|---|

|

Wolverhampton Skyline

Queen Square

Queens Building

Metro

|

||

|

||

Nickname(s):

|

||

| Motto(s):

Out of darkness cometh light

|

||

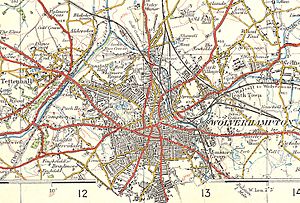

Wolverhampton shown within the West Midlands county

|

||

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom | |

| Country | England | |

| Region | West Midlands | |

| Ceremonial county | West Midlands | |

| Historic County | Staffordshire | |

| Founded | 985 | |

| City | 2000 | |

| Metropolitan borough | 1 April 1974 | |

| Founded by | Lady Wulfruna | |

| Named for | Lady Wulfruna | |

| Admin. HQ | Wolverhampton Civic Centre | |

| Suburbs of the city (Within 2 miles) |

List

Aldersley

All Saints Blakenhall Bradmore Chapel Ash Claregate Compton Deansfield Dunstall Hill East Park Ettingshall Fallings Park Gorsebrook Graiseley Heath Town Horseley Fields Merridale Monmore Green Newbridge Old Fallings Park Village Scotlands Springfield Stow Heath Tettenhall (village) Tettenhall Wood Wednesfield (town) Whitmore Reans |

|

| Government | ||

| • Type | Metropolitan borough | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 26.81 sq mi (69.44 km2) | |

| Elevation | 535 ft (163 m) | |

| Population | ||

| • Total | 263,700 | |

| • Density | 8,820/sq mi (3,407/km2) | |

| Demonym(s) | Wulfrunian | |

| Ethnicity (2021) | ||

| • Ethnic groups |

List

|

|

| Religion (2021) | ||

| • Religion |

List

43.8% Christianity

27.8% no religion 12% Sikhism 5.5% Islam 5.5% not stated 3.7% Hinduism 1.2% other 0.3% Buddhism 0.1% Judaism |

|

| Time zone | UTC+0 (Greenwich Mean Time) | |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (British Summer Time) | |

| Postcode |

WV

|

|

| Area code(s) | 01902 | |

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-WLV | |

| ONS code | 00CW (ONS) E08000031 (GSS) |

|

| OS grid reference | SO915985 | |

| NUTS 3 | UKG39 | |

Wolverhampton (![]() i/ˌwʊlvərˈhæmptən/ WUUL-vər-HAMP-tən) is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is about 12 miles (20 km) north of Birmingham. Wolverhampton is part of the larger West Midlands conurbation, with Walsall to the east and Dudley to the south. In 2021, its population was 263,700, making it the third largest city in the West Midlands.

i/ˌwʊlvərˈhæmptən/ WUUL-vər-HAMP-tən) is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands of England. It is about 12 miles (20 km) north of Birmingham. Wolverhampton is part of the larger West Midlands conurbation, with Walsall to the east and Dudley to the south. In 2021, its population was 263,700, making it the third largest city in the West Midlands.

Historically, Wolverhampton was part of Staffordshire. It started as a market town known for its wool trade. During the Industrial Revolution, it became a major hub for coal mining, steel, lock making, and car manufacturing. Today, the city's economy still focuses on engineering, including a big aerospace industry, and the service sector. Wolverhampton is also home to the University of Wolverhampton. It was a town for most of its history but became a city in 2000.

The M6 motorway runs near Wolverhampton's east and northeast sides. The M54 motorway starts to the north, connecting the city to Telford. For train travel, Wolverhampton station serves the city. The West Midlands Metro tram network also has its western end in Wolverhampton.

Wolverhampton is famous for its many musicians and artists. In sports, it's known for the Premier League football team Wolverhampton Wanderers FC, who play at Molineux Stadium. The city has a large Sikh community, who moved there from India between the 1930s and 1970s. They have helped shape the city's identity. Wolverhampton also has more Hindus and Muslims than the national average.

Contents

- What's in a Name? The Story of Wolverhampton's Name

- A Look Back: Wolverhampton's History

- Art and Culture in Wolverhampton

- Wolverhampton's Location and Environment

- How Wolverhampton is Governed

- People and Population in Wolverhampton

- Wolverhampton's Economy and Jobs

- Getting Around: Transport in Wolverhampton

- Culture and Entertainment

- Sports in Wolverhampton

- Places to Visit in Wolverhampton

- Famous People from Wolverhampton

- Images for kids

- See also

What's in a Name? The Story of Wolverhampton's Name

The city gets its name from Wulfrun, who founded the town in 985. The name comes from the old Anglo-Saxon words Wulfrūnehēantūn, meaning "Wulfrūn's high or main farm". Before the Norman Conquest in 1066, the area was called Heantune or Hamtun. The name Wulfrun was added around 1070.

Some people think the name might come from Wulfereēantūn, after King Wulfhere of Mercia. He was said to have started an abbey in 659, but there's no proof of this. The word Wulfrunian is used to describe someone from Wolverhampton.

A Look Back: Wolverhampton's History

A local story says that King Wulfhere of Mercia founded an abbey in Wolverhampton in 659.

Wolverhampton was the site of an important battle in 910. The Mercian Angles and West Saxons fought against the Danish invaders. Sources aren't clear if the battle was in Wednesfield or Tettenhall, both now part of Wolverhampton. The Mercians and West Saxons won a big victory.

In 985, King Ethelred the Unready gave land at a place called Heantun to Lady Wulfrun. This is how the settlement began.

In 994, a monastery was built in Wolverhampton. Wulfrun gave land for it in several nearby areas. This monastery became the site of the current St. Peter's Church. You can see a statue of Lady Wulfrun outside the church.

The Domesday Book of 1086 mentions Wolverhampton as a large settlement in Staffordshire. It had fifty households.

In 1179, there was a market in the town. In 1204, King John noticed the town didn't have a special Royal Charter for its market. King Henry III finally granted this charter on 4 February 1258, allowing a weekly market on Wednesdays.

In the 14th and 15th centuries, Wolverhampton was a key place for the wool trade. This is why a woolpack is on the city's coat of arms. Many small streets in the city centre are still called "Fold," like Blossom's Fold and Farmers Fold.

In 1512, Sir Stephen Jenyns, a former Lord Mayor of London who was born in the city, founded Wolverhampton Grammar School. It's one of Britain's oldest schools still running today.

From the 16th century, Wolverhampton became known for metal industries. These included making locks and keys, and working with iron and brass.

Wolverhampton had two big fires. The first was in April 1590, leaving almost 700 people without homes. The second was in September 1696, destroying 60 homes quickly. After the second fire, the city bought its first fire engine in 1703.

On 27 January 1606, two farmers were executed in Queen Square. They had hidden two of the Gunpowder Plotters.

Wolverhampton might also be where the first working Newcomen Steam Engine was used in 1712.

Wolverhampton in the 1800s

In the 1830s, before she became Queen, Queen Victoria visited Wolverhampton. She called it "a large and dirty town" but said people welcomed her warmly. During the Victorian times, Wolverhampton became rich because of its many industries. This was thanks to the large amounts of coal and iron found nearby.

You can still see this wealth in houses like Wightwick Manor and The Mount. These were built for the rich Mander family, who made varnish and paint. Many other grand houses were taken down in the 1960s and 1970s.

Wolverhampton got its first members of parliament in 1832. It was one of 22 large towns to get two MPs. In 1848, Wolverhampton became a municipal borough, and then a county borough in 1889.

Trains arrived in Wolverhampton in 1837. The first station was at Wednesfield Heath. This station was removed in 1965, but the area is now a nature reserve.

In 1866, a statue of Prince Albert was put up in Queen Square. Queen Victoria came back to Wolverhampton for its unveiling. This was her first public appearance after her husband's death. She was so happy with the statue that she knighted the mayor, John Morris. Market Square was renamed Queen Square in honor of her visit. The statue is still there and is known as "The Man on the Horse."

Wolverhampton in the 1900s

Wolverhampton had a busy bicycle industry from 1868 to 1975. Over 200 bicycle companies existed here, but none remain today.

Wolverhampton High Level station (the main train station today) opened in 1852. The original building was taken down in 1965 and rebuilt. Wolverhampton Low Level station opened in 1855 but closed to passengers in 1972. Part of it is now a hotel.

In 1918, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George gave his "Homes fit for heroes" speech at Wolverhampton Grand Theatre. This idea was important for his election campaign.

After World War I, Wolverhampton started building many council housing estates to rehouse families from poor areas. The Low Hill estate, built by 1927, had over 2,000 new houses. Building continued into the 1930s but stopped during World War II.

Wolverhampton St George's was the northern end of the West Midlands Metro tram system. An extension to the railway station opened in 2023. Wolverhampton was one of the few towns to use special surface contact trams. Trolleybuses also ran here from 1923, and for a short time in 1930, Wolverhampton had the world's largest trolleybus system. The last trolleybus ran in 1967.

England's first automatic traffic lights were put in Princes Square in 1927. The modern traffic lights there still have striped poles to remember this. Princes Square also had the UK's first pedestrian safety barriers, put up in 1934. In 1927, the A4123 New Road opened, connecting the city to Birmingham. This was the UK's first purpose-built intercity highway of the 20th century.

After World War II, the council built many new houses and flats. By 1975, almost a third of Wolverhampton's population lived in council housing. Some older areas, like Heath Town, were completely rebuilt in the 1960s with tall flats. However, these became unpopular, and some have been taken down and replaced.

Many black and Asian immigrants settled in Wolverhampton from the 1950s and 1960s. Today, about 12% of the city's population is Sikh.

In 1974, Wolverhampton became a metropolitan borough. On 31 January 2001, it was granted city status, becoming one of three "Millennium Cities."

Many buildings in the city centre are from the early 20th century or older. The oldest is St Peter's Collegiate Church, built in the 13th century. A 17th-century timber building on Victoria Street is also very old.

On 23 November 1981, a small tornado touched down in Fordhouses and moved over the city centre, causing some damage.

The Wolverhampton Ring Road goes around the city centre. It was built in parts between 1960 and 1986.

The city centre has changed a lot since the 1960s. The Mander Centre shopping mall opened in phases in 1968 and 1971. The Wulfrun Centre, another shopping area, opened in 1968 and was later covered with a roof.

The main police station was built on Bilston Street and opened by Diana, Princess of Wales in 1992.

The last city centre cinema, the ABC Cinema, closed in 1991. It was later a nightclub and was taken down in 2019 for a college extension. The Wolverhampton Combined Court Centre, a modern courthouse, opened in 1990.

Wolverhampton in the 2000s

Some department stores like Marks & Spencer and Next are in Wolverhampton city centre. Debenhams opened a store in the Mander Centre in 2017 but has since closed.

In 2021, a blue plaque was put up for Paulette Wilson, an immigrant rights activist from the Windrush generation. The plaque is at the Wolverhampton Heritage Centre.

Government Offices in Wolverhampton

On 20 February 2021, it was announced that the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (now the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government) would open a headquarters outside London. About 500 jobs, including senior staff, were planned to move to Wolverhampton by 2025. The Ministry's new offices in the i9 building opened on 10 September 2021.

Art and Culture in Wolverhampton

From the 1700s, Wolverhampton was known for making japanned ware (decorated metal) and steel jewelry. Famous artists like Joseph Barney and Edward Bird were born here and started as japanned ware painters.

The School of Practical Art opened in the 1850s. Many talented artists and sculptors studied or taught there.

Wolverhampton Art Gallery opened in 1884, and Wolverhampton Grand Theatre opened in 1894.

Wolverhampton has a Creative Industries Quarter with places like the Slade Rooms for music, the Light House Media Centre (an art house cinema that closed in 2022), and the Arena Theatre at the University of Wolverhampton.

The city has a rich history in painting designs on cast iron safes. Companies like Chubb Lock and Safe Company became famous worldwide for their artistic safes. The Chubb Building is now a historic landmark with a cinema, art galleries, and offices.

In 2017, the city had a big public art display called Wolves in Wolves. Thirty wolf sculptures were placed around the city centre and West Park. They were later sold to raise money for charity.

Exhibitions and Shows

As Wolverhampton grew, it took part in and hosted important exhibitions. The The Great Exhibition of 1851 in London showed locks, japanned ware, and papier-mâché products made in Wolverhampton.

In 1869, the Exhibition of Staffordshire Arts and Industry was held in a temporary building at Molineux House.

The biggest exhibition was the Arts and Industrial Exhibition in 1902. It had halls for machinery, industrial products, a concert hall, and a fun fair. It was opened by the Duke of Connaught.

Wolverhampton's Location and Environment

Wolverhampton is about 13 miles (21 km) northwest of Birmingham. It's the second largest part of the West Midlands conurbation. To the north and west, you'll find the countryside of Staffordshire and Shropshire.

The city centre of Wolverhampton is outside the area traditionally called the Black Country. However, some parts, like Bilston and Heath Town, are within the Black Country coalfields. Today, the term "Black Country" usually refers to the western part of the West Midlands county, not including Birmingham, Solihull, or Coventry.

The city sits on the Midlands Plateau, about 163 meters (535 ft) above sea level. There are no major rivers in the city itself. However, the River Penk and River Tame (which flow into the River Trent) start here. Also, Smestow Brook, which flows into the River Stour and then the River Severn, begins in Wolverhampton. This means the city is on a main watershed in England.

The ground beneath the city is a mix of different types of rock, including Triassic and Carboniferous geology.

Wolverhampton's Weather

Wolverhampton has an oceanic climate, which means it's quite mild. In July, the average high temperature is around 21°C (70°F). In January, the average daytime high is about 6.9°C (44.4°F).

The nearest weather station is at Penkridge, about 10 miles (16 km) north of the city.

| Climate data for Wolverhampton (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 14 (57) |

18 (64) |

21 (70) |

25 (77) |

27 (81) |

31 (88) |

35 (95) |

35 (95) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

21 (70) |

16 (61) |

35 (95) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

7.3 (45.1) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.8 (55.0) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.1 (66.4) |

21.5 (70.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

18.2 (64.8) |

14 (57) |

10 (50) |

7.2 (45.0) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.5 (34.7) |

1.2 (34.2) |

2.9 (37.2) |

4 (39) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.6 (49.3) |

11.7 (53.1) |

11.5 (52.7) |

9.6 (49.3) |

6.9 (44.4) |

3.9 (39.0) |

1.6 (34.9) |

5.9 (42.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −13 (9) |

−13 (9) |

−11 (12) |

−6 (21) |

−3 (27) |

−1 (30) |

3 (37) |

3 (37) |

−1 (30) |

−7 (19) |

−10 (14) |

−15 (5) |

−15 (5) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 58.2 (2.29) |

39.7 (1.56) |

47.6 (1.87) |

51.1 (2.01) |

55.7 (2.19) |

58.5 (2.30) |

55.5 (2.19) |

59 (2.3) |

60.5 (2.38) |

67.4 (2.65) |

64.5 (2.54) |

63.5 (2.50) |

681.2 (26.78) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 47.9 | 65.5 | 97.5 | 139.6 | 179.6 | 164.2 | 183.6 | 168.1 | 124.9 | 97.8 | 57.3 | 38.3 | 1,364.3 |

| Source: Penkridge extremes (nearest station) | |||||||||||||

Parts of the City

Most areas in Wolverhampton have names from Old English (Anglo-Saxon) times. Some exceptions include Penn and more modern names like Parkfields.

Here are some areas in the City of Wolverhampton:

- Aldersley

- All Saints

- Ashmore Park†

- Bilston †

- Blakenhall

- Bradley†

- Bradmore

- Bushbury

- Castlecroft

- Chapel Ash

- Claregate

- Compton

- Coseley (part) †

- Dunstall Hill

- East Park

- Ettingshall†

- Fallings Park

- Finchfield

- Fordhouses

- Goldthorn Park†

- Gorsebrook

- Graiseley

- Heath Town

- Horseley Fields

- Lanesfield†

- Low Hill

- Lower Penn (part) ††

- Merridale

- Merry Hill

- Monmore Green

- Newbridge

- Old Fallings

- Oxley

- Parkfields

- Park Village

- Pendeford

- Penn

- Penn Fields

- Portobello†

- Scotlands Estate

- Stow Heath

- Tettenhall†

- Tettenhall Wood†

- Warstones

- Wednesfield †

- Whitmore Reans

- Wightwick†

- Wood End†

- Woodcross†

- Notes

- †–These areas were partly added to Wolverhampton in 1966.

- ††–Areas within the Wolverhampton Urban Sub-division but managed by South Staffordshire District Council.

Nearby Places

Towns near Wolverhampton

Villages near Wolverhampton

- Albrighton

- Bilbrook

- Codsall

- Featherstone

- Himley

- Lower Penn

- Pattingham

- Penkridge

- Perton

- Seisdon

- Wombourne

Green Spaces in the City

Wolverhampton has green belt areas within its borders. These are green spaces that help stop the city from spreading out too much and protect natural areas. These green areas are mostly in the western half of the city.

Some of these green belt areas include:

- Moseley Parklands

- Ashmore Park

- Goldthorn/Lower Penn Green

- Smestow Valley/Valley Park

|

Telford | Penkridge | Cannock |  |

| Shrewsbury | Walsall | |||

| Swindon | Dudley | West Bromwich |

How Wolverhampton is Governed

Most of Wolverhampton is managed by the City of Wolverhampton Council. However, some smaller urban areas are managed by South Staffordshire District Council.

The City Council area has three Members of Parliament (MPs) representing Wolverhampton West, Wolverhampton South East, and Wolverhampton North East.

City of Wolverhampton Council

The City of Wolverhampton is a metropolitan borough. Its City Council acts as a single authority, providing most local services. The council offices are in the Wolverhampton Civic Centre in the city centre. The city council's motto is 'Out of darkness cometh light'.

The Labour Party currently controls the council. They have been the majority party since 1974, with only a few short breaks. In the 2023 election, the Labour party won 47 out of 60 council seats.

Local Government History

Wolverhampton started to get modern local government in 1777. Town Commissioners were set up to improve the area, like fixing drainage and adding street lighting. They also appointed watchmen for policing.

In 1837, the Wolverhampton Borough Police was formed. It later became part of the larger West Midlands Constabulary in 1966, which then became the West Midlands Police in 1974.

Wolverhampton became a municipal borough in 1848 and a County Borough in 1889.

In 1933, the borough's boundaries expanded. In 1966, more areas like Bilston, Tettenhall, and Wednesfield were added.

In 1974, Wolverhampton became part of the new West Midlands Metropolitan County. It was one of only two County Boroughs that didn't have its boundaries changed much during this time.

Police Services

The main police station for Wolverhampton is on Bilston Street in the city centre. Policing in the city is currently handled by West Midlands Police.

People and Population in Wolverhampton

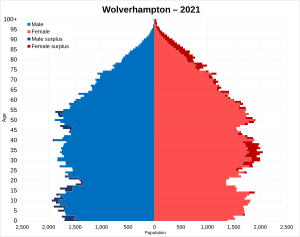

The 2021 Census shows that Wolverhampton's urban area is the second largest in the West Midlands conurbation, with 263,727 people. Slightly more females live in the city (50.9%) than males (49.1%).

Wolverhampton has a diverse population. In the 2021 census, 60.6% of people were white, 21.2% were Asian, 9.3% were Black, 5.3% were mixed, and 3.6% were from other ethnic groups.

Based on the 2021 census, 43.8% of Wolverhampton's population is Christian. About 27.8% said they had no religion. Sikhism is the second largest religion, with 12% of the population in 2021. This means Wolverhampton has the largest percentage of Sikhs in England and Wales. The proportion of people following Islam was 5.5%, and Hinduism was 3.7%.

Wolverhampton is among the top 11% of local areas in England and Wales for using public transport to get to work (16%). Most people (63%) use private transport. Car ownership is lower than the national average, with 35.2% of households not owning a car.

Population Changes Over Time

The tables below show how the population of Wolverhampton and the area it covers has changed since 1750.

| Historical population of Wolverhampton | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Issac Taylor's Map 1750 • Township 1801–1881 • Urban Sanitary District 1891 • County Borough 1901–1971 • Urban Subdivision 1981–2011 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical population of area now administered by Wolverhampton City Council | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Vision of Britain | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ethnic Groups in Wolverhampton

| Ethnic Group | 1971 estimations | 1981 estimations | 1991 census | 2001 census | 2011 census | 2021 census | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| White: Total | 240,313 | 89.3% | 215,659 | 85% | 201,644 | 81.1% | 184,044 | 77.8% | 169,682 | 68% | 159,707 | 60.5% |

| White: British | – | – | – | – | – | – | 178,319 | 75.4% | 160,945 | 64.5% | 144,303 | 54.7% |

| White: Irish | – | – | – | – | – | – | 2,422 | 1,526 | 1,170 | 0.4% | ||

| White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 209 | 706 | 0.30% | |

| White: Other | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3,303 | 1.4% | 7,002 | 2.8% | 13,528 | 5.1% |

| Asian or Asian British: Total | – | – | 25,744 | 10.1% | 32,289 | 13% | 34,713 | 14.7% | 44,960 | 18% | 55,901 | 21% |

| Asian or Asian British: Indian | – | – | 23,184 | 28,887 | 29,153 | 12.3% | 32,162 | 12.9% | 42,052 | 15.9% | ||

| Asian or Asian British: Pakistani | – | – | 1,548 | 2,074 | 2,931 | 4,415 | 6,676 | 2.5% | ||||

| Asian or Asian British: Bangladeshi | – | – | 110 | 187 | 211 | 432 | 531 | 0.2% | ||||

| Asian or Asian British: Chinese | – | – | 306 | 395 | 843 | 1,376 | 802 | 0.3% | ||||

| Asian or Asian British: Other Asian | – | – | 596 | 746 | 1,575 | 6,575 | 5,840 | 2.2% | ||||

| Black or Black British: Total | – | – | 10,939 | 4.3% | 12,938 | 5.2% | 10,874 | 4.6% | 17,309 | 6.9% | 24,636 | 9.3% |

| Black or Black British: Caribbean | – | – | 8,846 | 10,364 | 9,116 | 9,507 | 9,905 | 3.8% | ||||

| Black or Black British: African | – | – | 283 | 319 | 690 | 4,081 | 11,158 | 4.2% | ||||

| Black or Black British: Other Black | – | – | 1,810 | 2,255 | 1,068 | 3,721 | 3,573 | 1.4% | ||||

| Mixed or British Mixed: Total | – | – | – | – | – | – | 6,441 | 2.7% | 12,784 | 5.1% | 14,065 | 5.4% |

| Mixed: White and Black Caribbean | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4,238 | 8,495 | 8,495 | 3.2% | ||

| Mixed: White and Black African | – | – | – | – | – | – | 232 | 554 | 939 | 0.4% | ||

| Mixed: White and Asian | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1,144 | 2,160 | 2,573 | 1.0% | ||

| Mixed: Other Mixed | – | – | – | – | – | – | 827 | 1,575 | 2,058 | 0.8% | ||

| Other: Total | – | – | 1,314 | 0.5% | 1,630 | 0.7% | 510 | 0.2% | 4,735 | 1.9% | 9,417 | 3.6% |

| Other: Arab | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 359 | 966 | 0.4% | |

| Other: Any other ethnic group | – | – | 1,314 | 0.5% | 1,630 | 0.7% | 510 | 0.2% | 4,376 | 1.8% | 8,451 | 3.2% |

| Ethnic minority | 28,853 | 10.7% | 37,997 | 15% | 46,856 | 18.9% | 52,538 | 22.2% | 79,788 | 32% | 96,434 | 39.5% |

| Total | 269,166 | 100% | 253,656 | 100% | 248,500 | 100% | 236,582 | 100% | 249,470 | 100% | 263,726 | 100% |

Religion in Wolves (2021) Christianity (43.85%) No Religion (27.80%) Sikhism (12.05%) Islam (5.49%) Hinduism (3.75%) Buddhism (0.35%) Judaism (0.04%) Other Religions (1.20%) Religion not Stated (5.48%)

Religious Beliefs in Wolverhampton

The table below shows the religious beliefs of people in Wolverhampton from recent censuses.

| Religion | 2001 Census | 2011 Census | 2021 Census | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Christian | 157,300 | 66.49% | 138,394 | 55.48% | 115,640 | 43.85% |

| Sikh | 17,944 | 7.58% | 22,689 | 9.09% | 31,769 | 12.05% |

| Muslim | 4,060 | 1.72% | 9,062 | 3.63% | 14,489 | 5.49% |

| Hindu | 9,198 | 3.89% | 9,292 | 3.72% | 9,882 | 3.75% |

| Buddhist | 737 | 0.31% | 1,015 | 0.41% | 915 | 0.35% |

| Jewish | 104 | 0.04% | 88 | 0.04% | 94 | 0.04% |

| Other religion | 511 | 0.22% | 3,057 | 1.23% | 3,158 | 1.20% |

| No religion | 26,927 | 11.38% | 49,821 | 19.97% | 73,317 | 27.80% |

| Religion not stated | 19,801 | 8.37% | 16,052 | 6.43% | 14,465 | 5.48% |

| Total | 236,582 | 100.00% | 249,470 | 100.00% | 263,729 | 100.00% |

Wolverhampton's Economy and Jobs

Wolverhampton's economy used to be mainly about iron, steel, cars, and manufacturing. Many of these older industries have closed or become much smaller. However, by 2008, the service sector was the biggest part of the economy, providing 74.9% of jobs.

The largest employers in the service sector are public administration, education, and health. Other big parts are shops, hotels, restaurants, finance, and IT. Manufacturing still makes up 12.9% of jobs. Tourism also supports 5.2% of jobs.

The biggest employer in the city is Wolverhampton City Council, with over 12,000 staff. Other large employers include:

- Banking: Birmingham Midshires (Headquarters)

- Building materials: Tarmac and Carvers Builders Merchant

- Education: University of Wolverhampton and City of Wolverhampton College

- Brewing: Marston's (Headquarters)

- Aerospace: H S Marston, MOOG and Goodrich Actuation Systems

- Manufacturing: Chubb Locks, Jaguar Land Rover (Engine Assembly Plant)

- NHS: New Cross Hospital

Jaguar Land Rover's Engine Plant

In 2014, Jaguar Land Rover opened a £500 million engine assembly plant at the i54 business park in Wolverhampton. Queen Elizabeth II officially opened the plant. It makes 2.0-litre 4-cylinder Ingenium diesel and petrol engines. The factory has already been expanded once. In 2015, it was announced that the factory would double in size, costing $450 million. This expansion was expected to double the workforce from 700 to 1,400.

Goodyear Tyre Factory

Goodyear opened a large factory in Fordhouses in 1927. However, in December 2003, they decided to stop making tyres there, leading to over 400 job losses. Tyre production ended in 2004, but the factory still did tyre moulding and tractor tyre production.

Wolverhampton Wanderers Football Club

The success of Wolverhampton Wanderers (Wolves) since 1877 has also helped Wolverhampton's economy. The club's best years were from 1949 to 1960, when they won the league title three times and the FA Cup twice. They also played famous friendly matches against top European clubs. Wolves often attracted crowds of 40,000 to 50,000 people.

Wolves won the Football League Cup in 1974 and 1980. The 1980s were tough for the club, with three relegations and falling attendance. This happened when Wolverhampton's economy was also struggling. However, Wolves improved in the late 1980s with two promotions, thanks to striker Steve Bull. This brought more fans and boosted the local economy. The stadium was rebuilt in the 1990s, adding restaurants and offices. In 2018, Wolves were promoted to the FA Premier League.

Tallest Buildings in Wolverhampton

| Rank | Building | Use | Height | Floors | Built |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Victoria Halls (Building 1) | Residential | 246 ft (75 m) | 25 | 2009 |

| 2= | Brockfield House | Residential | 203 ft (62 m) | 22 | 1969 |

| 2= | Hampton View | Residential | 203 ft (62 m) | 22 | 1969 |

| 4= | St. Cecilias | Residential | 184 ft (56 m) | 20 | 1970 |

| 4= | Wodensfield Tower | Residential | 184 ft (56 m) | 20 | 1966 |

| 4= | William Bentley Court | Residential | 184 ft (56 m) | 20 | 1966 |

| 4= | Longfield House | Residential | 184 ft (56 m) | 20 | 1969 |

| 4= | Campion House | Residential | 184 ft (56 m) | 20 | 1969 |

| 9 | St Peter's Collegiate Church | Church | 171 ft (52 m) | 1480 | |

| 10 | Pennwood Court | Residential | 151 ft (46 m) | 17 | 1968 |

City Improvements and New Projects

Wolverhampton City Council has been working on many city improvements. One big project was "Summer Row," a new shopping area planned for the city centre. This project was cancelled in 2011 due to the 2008 recession.

Mander Centre Shopping Mall Changes

Debenhams wanted to open a department store in Wolverhampton. They opened a large store in a £35 million redevelopment of the Mander Centre in 2017. This created 120 jobs. The Mander Centre was also fully updated and rearranged. Debenhams closed in January 2020. In 2019, Wilkinson moved into the Mander Centre, and B & M Stores opened in part of the old BHS store.

Wolverhampton Interchange Project

Wolverhampton's Interchange Project is a big plan to redevelop the city's east side, costing around £120 million.

- Phase 1: Finished in 2012, this involved taking down the old bus station and building a new £22.5 million one. It also included a new footbridge to the train station and new offices.

- Phase 2: Finished in late 2015, this built the £10.6 million i10 building next to the new bus station. This building has shops and restaurants on the ground floor and offices above.

- Phase 3: Started in early 2016, this expanded the train station's multi-storey car park. It was finished in December 2016, increasing spaces from 450 to over 800.

- Phase 4: This involved building the i9 development. The offices in i9 are used by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, part of the central government.

Getting Around: Transport in Wolverhampton

Road Travel

Wolverhampton city centre is a key point for roads in the northwest of the West Midlands conurbation. The city's roads are managed by Wolverhampton City Council.

Important road improvements include Thomas Telford's Holyhead Road (now part of A41), built between 1819 and 1826. In 1927, the A4123 Birmingham-Wolverhampton New Road was built. This was the UK's first purpose-built inter-city highway of the 20th century. Also in 1927, the first automatic traffic lights in the UK were installed in Princes Square. This square also had the UK's first pedestrian safety barriers in 1934.

In 1960, plans for a Ring Road around the city centre were announced. Most of it was finished by the end of the 1960s, and the final part was completed in 1986.

Wolverhampton is close to several motorways. The M6 opened between 1966 and 1970, connecting the city to the north-west, Scotland, Birmingham, and London. The M5 opened in 1970, linking the city to the south-west. These two motorways help bypass the city. The M6 Toll road, opened in 2003, helps ease traffic on the busy M6.

The M54 motorway forms a northern bypass for the city. It connects Wolverhampton to Telford, Shrewsbury, and Wales. It opened in 1983.

Train Travel

Wolverhampton has good train connections to other parts of England and Wales. However, many suburbs no longer have train stations.

Wolverhampton's first railway opened in 1837. The main station was at Wednesfield Heath, which is now a nature reserve.

The first city centre station opened in 1849. The permanent station, now called Wolverhampton station, opened in 1852. Another station, Wolverhampton Low Level, opened in 1855 but closed to passengers in 1972.

Today, Wolverhampton station is a main station on the West Coast Main Line. It has regular services to London Euston, Birmingham New Street, and Manchester Piccadilly. There are also local services to Wales, Walsall, Telford, Shrewsbury, and Stafford.

The station buildings from the 1960s were taken down and replaced with a modern station. Phase 1 opened in spring 2020, and Phase 2 opened on 28 June 2021. This new station includes a stop for the Metro tram line, which opened in September 2023.

Bus Services

National Express West Midlands is the biggest bus company in Wolverhampton. Other companies include Diamond West Midlands and Arriva Midlands. Buses from the city centre go to suburbs and other towns like Birmingham, Walsall, Telford, and Dudley.

Transport for West Midlands runs Wolverhampton bus station on Pipers Row. It was completely rebuilt in 2011 and is near the train station, making it easy to switch between bus, train, and tram.

West Midlands Metro Tram System

The West Midlands Metro, a light rail system, connects Wolverhampton St George's to Grand Central tram stop in Birmingham. It mostly follows the route of an old railway line. There were plans for more lines in the city, but these were cancelled in late 2015.

All seven of the westernmost stations on the network are in Wolverhampton. This number increased to nine when Pipers Row and Wolverhampton station were connected to the network.

In 2014/15, Centro announced they would replace all 16 old trams with 21 new CAF Urbos 3 trams. The new trams are longer and can carry more passengers. The Metro line was extended from Wolverhampton St George's to Wolverhampton railway station, adding a stop at Wolverhampton bus station. This extension opened in summer 2023.

In 2021, funding was given for new Metro projects, including a line from Wolverhampton to New Cross Hospital. This new line will extend the existing line from Wolverhampton Interchange to the hospital.

Air Travel

Wolverhampton's first airport was at Pendeford, which opened in 1938 and closed in 1970. The current Wolverhampton Airport, formerly Halfpenny Green, is a small airfield about 8 miles (13 km) southwest of the city. It hosts various events and was an original World War Two airfield.

The closest major airport is Birmingham Airport, about 25 miles (40 km) away. It's easy to reach by train, taking about 36 minutes. By car, it takes about 45 minutes.

Waterways and Canals

Wolverhampton doesn't have navigable rivers, but it has 17 miles (27 km) of navigable canals. The Birmingham Canal Main Line goes through the city centre. It connects with other canals like the Wyrley & Essington Canal and the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal. The canal also goes through 21 locks in Wolverhampton.

Cycling in Wolverhampton

Most places in the city and nearby villages are easy to reach by bike. The city centre has a 20 mph (32 km/h) speed limit, and there are quieter routes to avoid busy roads. Wolverhampton is on Sustrans National Cycle Network Route 81. This route follows canal towpaths and also has a path through the city centre and West Park. The lanes in nearby South Staffordshire and east Shropshire are great for bike tours.

Culture and Entertainment

Music Scene

Many famous music groups and artists come from Wolverhampton. These include rock bands Slade and Cloven Hoof, electronic musician Bibio, soul singer Beverley Knight, and drum and bass artist Goldie. Kevin Rowland of Dexys Midnight Runners was born in Wednesfield.

Hip Hop producer S-X, who has worked with big names like T.I. and Lil Wayne, was born and raised in Wolverhampton. In 2010, Wolverhampton-born singer Liam Payne (1993–2024) became famous with his boy band One Direction. They were the first British group to reach number one on the US music charts with their first album.

Wolverhampton has several places for live music. The largest is sometimes the football ground, Molineux Stadium. The biggest indoor venue is Wolverhampton Civic Hall, which can hold 3,000 people. Wulfrun Hall, part of the same complex, holds over 1,100. The Slade Rooms, named after the 1970s rock band, holds about 550. There are also smaller venues. The 18th-century St John's Church hosts classical concerts.

Arts and Museums

The Grand Theatre on Lichfield Street is Wolverhampton's largest theatre. It opened on 10 December 1894. Famous people like Charlie Chaplin have performed there. Politicians like Winston Churchill also used it.

The Arena Theatre at the University of Wolverhampton is a smaller theatre, seating 150. It hosts both professional and amateur shows.

For movies, there's a Cineworld multiplex at Bentley Bridge, Wednesfield. The Light House Media Centre, located in the former Chubb Buildings, showed older and subtitled films. The Lighthouse closed on 3 November 2022.

The city's Arts & Museums service runs three sites:

- Wolverhampton Art Gallery: Home to one of England's biggest Pop art collections.

- Bantock House: A historic house with an Edwardian interior and a museum about Wolverhampton.

- Bilston Craft Gallery: Shows contemporary crafts.

The Black Country Living Museum in nearby Dudley has many items and buildings from the Black Country, including some from Wolverhampton.

Eagle Works Studios and Gallery in Chapel Ash is run by artists. It has studios for visual artists and a gallery for contemporary art.

The National Trust owns two properties near the city that are open to the public:

- Wightwick Manor: A Victorian manor house built and furnished in the Arts and Crafts movement style.

- Moseley Old Hall: Famous as a hiding place for Charles II of England when he was escaping to France in 1651.

English Heritage owns Boscobel House in Shropshire, another place where Charles II hid.

Libraries in Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton Central Library is a Grade II listed building on Garrick Street. It was designed by Henry T. Hare and opened in 1902. It was built to celebrate Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee. The outside of the building has carvings of the Royal Coat of Arms and the Wolverhampton Coat of Arms. It also features names of famous English writers like Shakespeare and Milton.

Wolverhampton City Council also runs 14 other branch libraries around the city.

Local Media

Wolverhampton is home to the Express & Star newspaper. It has the largest circulation of any local daily evening newspaper in the UK.

Local TV news is provided by BBC Midlands Today and ITV News Central.

The local BBC radio station is BBC Radio WM on 95.6 FM.

Wolverhampton used to have several local radio stations. Now, the only one based in the city is the community radio station WCR FM, which broadcasts on 101.8FM.

In 2005, the BBC asked poet Ian McMillan to write a poem about Wolverhampton. The film Made in Wolverhampton (2013) explores the city's hidden history and architecture.

Sports in Wolverhampton

Football

Wolverhampton is represented in the Premier League, the top level of English football, by Wolverhampton Wanderers FC. Known as 'Wolves', they are one of England's oldest football clubs and were one of the 12 founding members of the Football League. Their most successful time was the 1950s, when they won three league titles and two FA Cups. They also played in early European friendly matches.

In total, Wolves have won three top-division titles, four FA Cups, and two League Cups. They reached the UEFA Cup Final in 1972. They are one of only two clubs to have won five different league titles in England.

Wolves have a long-standing rivalry with West Bromwich Albion. They are also rivals with Aston Villa and Birmingham City FC.

Several other local clubs play non-league football, including AFC Wulfrunians and Wolverhampton Sporting Community F.C..

Athletics

Wolverhampton's Aldersley Leisure Village is home to Wolverhampton & Bilston Athletics Club. This club has won national titles and represented Britain in European competitions.

Olympic medalists in athletics, Sonia Lannaman and Tessa Sanderson, lived in the city.

Cricket

There are several cricket clubs in the city, such as Wolverhampton Cricket Club and Fordhouses Cricket Club.

Field Hockey

Wolverhampton has a few field hockey clubs that play in the Midlands Hockey League. These include Wolverhampton & Tettenhall Hockey Club.

Cycling

Wolverhampton Wheelers is the city's oldest cycling club, formed in 1891. It was home to Hugh Porter, who won four world championship pursuit titles. Percy Stallard is credited with starting cycle road racing in Britain with a race from Llangollen to Wolverhampton in 1942. Wolverhampton Wheelers use the velodrome at Aldersley Stadium.

Wolverhampton has also hosted the Tour of Britain cycling race several times.

Horse and Greyhound Racing

Wolverhampton Racecourse is at Dunstall Park, north of the city centre. It was one of the first all-weather horse racing courses in the UK and is Britain's only floodlit horse race track. There is also greyhound racing at Monmore Green. West Park, a large park, used to be a racecourse.

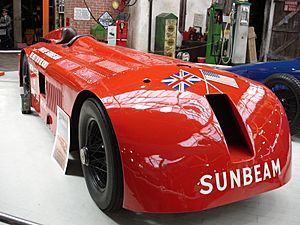

Motor Sports

Sunbeam built many early Grand Prix cars. It was the only British company to win a Grand Prix in the first half of the 20th century. Sunbeam also built cars that set Land speed records, including the first vehicle to go over 200 mph (320 km/h).

AJS was very involved in motorcycle racing, winning the 1949 World Championship in the 500cc category.

Wolverhampton Wolves, a leading speedway club, represents the city. They race in the Elite League at Monmore Green stadium. Wolverhampton Speedway is one of the oldest speedway tracks still in use.

Le Mans 24 Hours winner Richard Attwood is from the city.

Marathon Race

Wolverhampton hosts the Carver Wolverhampton City Marathon. This marathon helps raise money for charity.

Obstacle Course Race

The Tough Guy Race, considered the first civilian obstacle course race, is held annually near Wolverhampton.

Commonwealth Games

Wolverhampton hosted the Cycling Time Trials for the 2022 Commonwealth Games on 4 August 2022. The race started and finished at West Park, going through the city centre and suburbs.

Places to Visit in Wolverhampton

| Key | |

| Owned by the National Trust | |

| Owned by English Heritage | |

| Owned by the Forestry Commission | |

| A Country Park | |

| An Accessible open space | |

| Museum (free) | |

| Museum (charges entry fee) | |

| Heritage railway | |

| Historic House | |

- Bantock House Museum and Park

- Bilston Craft Gallery

- Mander Centre

- Molineux Stadium (Wolverhampton Wanderers F.C.)

- Moseley Old Hall

- St Peter's Collegiate Church

- West Park

- Wightwick Manor

- Wolverhampton City Archives

- Wolverhampton Art Gallery

- Wolverhampton Civic Hall

- Wolverhampton Grand Theatre

- Wolverhampton Racecourse

- Wolves in Wolves

Famous People from Wolverhampton

Many notable people are connected to Wolverhampton.

In politics, figures include Enoch Powell MP, Sir Charles Pelham Villiers MP (who served the longest as an MP), and Helene Hayman, Baroness Hayman, the first Lord Speaker in the House of Lords. Former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson briefly worked as a writer for the Express & Star.

Sports stars from the city include footballers Billy Wright and Steve Bull. Cyclists Percy Stallard and Hugh Porter, Olympic swimmer Anita Lonsbrough, and athletes Tessa Sanderson and Denise Lewis are also from here.

Entertainers include actors Nigel Bennett, Goldie, and Meera Syal. Musicians include Noddy Holder, Beverley Knight, Robert Plant, and Liam Payne from One Direction.

In business and industry, famous names include Sir Alfred Hickman (first Chairman of Tarmac) and Mervyn King, the former Governor of the Bank of England.

List of Freemen of the City of Wolverhampton

The following people have been given the special title 'Freeman of Wolverhampton':

- Henry Hartley Fowler, MP, 11 February 1892

- Charles Pelham Villiers MP, 11 May 1897

- Sir Charles Tertius Mander, 24 May 1897

- Sir Joseph Cockfield Dimsdale, MP, 29 July 1902

- Sir Alfred Hickman, MP, 29 July 1902

- William Highfield Jones, 29 July 1902

- Sir George Hayter Chubb, 14 October 1909

- John Marston, 14 October 1909

- Joseph Jones, 14 August 1912

- David Lloyd George MP, 23 November 1918

- Field Marshal Earl Haig of Bemersyde, 16 October 1919

- Albert Baldwin Bantock, 9 November 1926

- Levi Johnson, 9 November 1926

- Thomas William Dickinson, 18 July 1938

- Thomas Austin Henn, 7 October 1943

- Alan Davies, 29 October 1945

- Sir Charles Arthur Mander, 29 October 1945

- Joseph Harold Sheldon (1920–1964), 24 March 1958. Pediatrician, see Freeman–Sheldon syndrome

- Sir Charles Wheeler, 24 March 1958

- Denise Lewis, 13 December 2000

- Sir Jack Hayward, 9 July 2003

- Dennis Turner, Baron Bilston, 20 December 2006

- Hugh Porter, 17 December 2008

- Baroness Heyhoe Flint, 3 November 2010

- Beverley Knight, 16 May 2018

- Steve Bull, 11 September 2018

On 19 August 2006, freedom was also given to veterans of the Princess Irene Brigade. These were members of the Dutch Army who were stationed at Wrottesley Park during World War II.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Wolverhampton para niños

In Spanish: Wolverhampton para niños

| Sharif Bey |

| Hale Woodruff |

| Richmond Barthé |

| Purvis Young |