History of the Jews in England facts for kids

The history of the Jews in England tells the story of Jewish people living in England, starting from the time of William the Conqueror. While there might have been some Jewish people in England during the Roman period, we don't have clear proof of a community until 1070. Jewish settlement continued until King Edward I ordered them to leave in 1290.

After this expulsion, there wasn't an open Jewish community in England for a long time. Some individuals might have practiced Judaism secretly. It wasn't until the time of Oliver Cromwell in the 1600s that a small group of Sephardic Jews (Jews from Spain and Portugal) were found living in London in 1656 and allowed to stay.

In 1753, a law called the Jewish Naturalisation Act 1753 tried to make it legal for Jews to live in England, but it only lasted a few months. Historians often say that Jewish people gained full rights in England around 1829 or 1858. Interestingly, Benjamin Disraeli, who was born Jewish but became an Anglican, was elected Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice in the late 1800s. In 1846, a old British law that made Jews wear special clothes was removed.

Because there wasn't much anti-Jewish violence in Britain in the 1800s, the country became known for its religious tolerance. Many Jewish people from Eastern Europe moved there. By the start of World War II, about half a million European Jews tried to escape the Nazis by coming to England. However, only about 70,000 (including almost 10,000 children through the Kindertransport) were allowed to enter.

Jews in Britain sometimes faced antisemitism (prejudice against Jews) and stereotypes. During World War I, antisemitism often mixed with anti-German feelings, even though the British royal family had some German roots. This led many Ashkenazi Jews (Jews from Central and Eastern Europe) to change their German-sounding names to English ones.

Today, there are about 275,000 Jews in the UK, with over 260,000 living in England. This makes England home to the second largest Jewish population in Europe (after France) and the fifth largest Jewish community worldwide. Most Jews in England live in and around London. Other important communities are in Greater Manchester, Leeds, Gateshead, Brighton, Liverpool, Birmingham, and Southend.

Contents

Early Jewish Life in England

Roman and Anglo-Saxon Times

It's possible that Jewish people lived in Roman Britain, perhaps as soldiers, slaves, or traders. However, there isn't much clear proof. One story from Caerleon (in Wales) mentions two Roman-era Christian martyrs named Julius and Aaron, and the name Aaron might suggest Jewish origins.

There's little to suggest a settled Jewish community in Anglo-Saxon England. Although Jewish religion and its connection to Christianity were discussed in writings, the few mentions in Anglo-Saxon church laws only relate to Jewish practices around Easter.

Jewish Life in Norman England (1066–1290)

William of Malmesbury wrote that William the Conqueror brought Jews from Rouen in France to England during the Norman Conquest. William likely wanted them to help with his plan to collect taxes in coins instead of goods. For this, he needed people across the country who could provide coins.

How Jews Lived in England

Before they were expelled in 1290, the lives of Jews in England depended completely on the king. English Jews were legally under the king's control. He protected them because they were important for the economy. They were like "royal serfs," meaning they belonged to the king. This allowed them to travel freely, avoid certain taxes, own land directly from the king, and find safety in the king's many castles.

Jews in London were protected by the Constable of the Tower. They could seek refuge in the Tower of London when there was mob violence. This happened several times, with many Jews staying there for months. Records even show Jewish men-at-arms helping to guard the Tower in 1267 during a civil war.

King Henry I gave a special charter (a legal document) to Rabbi Joseph, the chief Rabbi of London, and his followers. This charter allowed Jews to travel without paying tolls, to buy and sell, and to sell items they had taken as security for loans after a year and a day. They could also be judged by other Jews and swear oaths on the Torah instead of a Christian Bible. A Jew's oath was considered very important. The charter also said Jews could move wherever they wanted, as if they were the king's own property. Because they were the king's property, English Jews could be taxed heavily without the permission of Parliament, and they eventually became the main group paying taxes.

Jews in England had a "golden age" under Henry II in the late 1100s. This was due to a big growth in the economy and a high demand for loans. Many Jews became very wealthy in cities like London, Oxford, and Lincoln, England. The king also benefited from their wealth. Besides many unfair taxes, Richard I created the Ordinance of the Jewry in 1194 to organize the Jewish community. This law made sure that royal officials kept records of all Jewish business deals. Every debt was recorded, giving the king full access to Jewish property. Richard also set up a special office to collect any unpaid debts after a Jewish lender died. This office, called the Exchequer of the Jews, meant that all Jewish business was taxed by the king, plus 10% of all money Jews recovered with the help of English courts. So, even though the First and Second Crusades increased anti-Jewish feelings, Jews in England were mostly safe under the king's protection. Their population and wealth grew.

The situation for Jews in England got much worse in the late 1100s. As the government became stronger and religious devotion deepened, Jews became more isolated from the rest of English society. Even though church and state leaders used Jewish advancements in business, ordinary people's anti-Jewish feelings grew. This was because of Jewish prosperity and their close ties to the king and courts. Outside pressures, like the false story of the blood libel (a lie that Jews killed Christian children for rituals), religious tensions from the Crusades, and the involvement of Pope Innocent III, created a very dangerous environment for English Jews. Mob violence increased against Jews in London, Norwich, and Lynn. Entire Jewish communities were murdered in York. However, because they were so useful financially, English Jews still received royal protection. Richard I continued to order their protection, setting up official record-keeping places to better protect records of all Jewish transactions.

The poor leadership of King John in the early 1200s made even the wealthiest Jews poor. And though they had some time to recover, Henry III's equally bad financial management took about £70,000 from a Jewish population of only 5,000. To pay this, Jews had to sell many of their loan agreements to rich nobles. The Jews then became the target of hatred from these debtors, and violence increased again in the mid-1200s. Their legal status didn't change until Henry's son, Edward I, took control. He passed strict laws, stopping them from lending money, which was how they made a living. With almost no way to earn money and their property being taken, the Jewish population shrank. New waves of religious passion in the 1280s, along with anger over debts, pushed Edward to expel the remaining Jewish community in 1290.

Kings' Views on Jews

Relations between Christians and Jews in England were troubled under King Stephen. He burned down a Jewish man's house in Oxford (some say with the man inside) because he refused to pay money to the king. In 1144, the first report of the blood libel against Jews appeared, in the case of William of Norwich. Anthony Julius says that the English were very creative in making up anti-Jewish accusations. He believes England became the main place for inventing literary antisemitism. He argues that the blood libel was key because it included ideas that Jews were evil, always plotting against Christians, powerful, and cruel. Other stories included Jews poisoning wells or buying and selling Christian souls.

While Crusaders were killing Jews in Germany, King Stephen prevented similar attacks against Jews in England, according to Jewish writers.

When order was restored under Henry II, Jews became active again. Within five years of his rule, Jews were found in many towns like London, Oxford, and Cambridge. However, they were only allowed to bury their dead in London until 1177. Their presence across the country allowed the king to get money from them when needed. He paid them back with notes that county sheriffs had to honor. Strongbow's conquest of Ireland (1170) was paid for by Josce, a Jewish man from Gloucester. The king fined Josce for lending money to people the king disliked. Generally, Henry II didn't seem to limit Jewish financial activities. The good position of English Jews was shown by visits from important Jewish scholars like Abraham ibn Ezra in 1158. Also, Jews who were forced out of the king's lands in France by Philip Augustus in 1182 moved to England.

In 1168, when making an alliance with Frederick Barbarossa, Henry II arrested the main Jewish leaders and sent them to Normandy. He then demanded a tax of 5,000 marks from the rest of the community. However, when he asked the rest of the country to pay a tithe (a tax for the church) for the Crusade against Saladin in 1188, he demanded a quarter of all Jewish belongings. This "Saladin tithe" was estimated at £70,000, with the Jewish quarter being £60,000. This meant the value of Jewish personal property was considered one-fourth of the entire country's wealth. It's unlikely the full amount was paid at once, as arrears were demanded from Jews for many years.

Aaron of Lincoln is thought to have been the wealthiest man in 12th century Britain. His wealth might have been more than the king's. The king probably made this large demand on English Jewry's money because of the surprising amount of wealth that came to his treasury when Aaron died in 1186. All property gained through lending money with interest, whether by a Jew or Christian, went to the king when the lender died. Aaron of Lincoln's estate included £15,000 worth of debts owed to him. A special part of the treasury, called "Aaron's Exchequer", was set up to handle this large amount.

In the early years of Henry II's reign, Jews got along well with their non-Jewish neighbors, including church leaders. They could enter churches freely and found safety in abbeys during times of trouble. Some Jews lived in grand houses and helped build many of the country's abbeys and monasteries. However, by the end of Henry's reign, they had upset the upper classes. Anti-Jewish feelings, encouraged by the Crusades, spread throughout the nation.

Persecution and Expulsion

The persecution of Jews in England was harsh. Massacres happened in London, Northampton, and York during the crusades in 1189 and 1190. The massacre at York was said to be more about greed than religious reasons. In 1269, Henry III made blasphemy by Jews a crime punishable by hanging. When Edward returned from a Crusade, he passed the Statute of Jewry in 1275. There were about 2,000 Jews in England at this time.

To pay for his war against Wales in 1276, Edward I taxed Jewish moneylenders. When they couldn't pay, they were accused of disloyalty. Edward had already limited their jobs. He then took away their right to lend money, restricted their movements, and forced Jews to wear a yellow patch. The heads of Jewish families were arrested, with over 300 taken to the Tower of London and executed. Others were killed in their homes.

On November 17, 1278, all Jews in England, thought to be around 3,000 people, were arrested because they were suspected of coin clipping (shaving off small bits of precious metal from coins) and counterfeiting. All Jewish homes were searched. Coin clipping was common then, done by both Jews and Christians. It caused a financial crisis, reducing the value of money by half. In 1275, coin clipping became a crime punishable by death. In 1278, raids were carried out on suspected coin clippers. The Bury Chronicle said, "All Jews in England of whatever condition, age or sex were unexpectedly seized … and sent for imprisonment to various castles throughout England." About 680 were held in the Tower of London. More than 300 are believed to have been executed in 1279. Those who could afford to pay for a pardon and had a powerful friend at the royal court escaped punishment.

Edward I showed more and more antisemitism. In 1280, he allowed a special toll to be charged at the Brentford bridge: 1 penny for Jews and Jewesses on horseback, and 0.5 penny on foot, while all other travelers were free. This dislike eventually led him to order the expulsion of all Jews from the country in 1290. Most were only allowed to take what they could carry. A few Jews favored by the king could sell their properties first, but most of the money and property of these dispossessed Jews was taken by the king. Almost all proof of a Jewish presence in England would have been lost if it weren't for a monk named Gregory of Huntingdon, who bought all the Jewish texts he could to translate them.

From then until 1655, there is no official record of Jewish communities in England, except for a few individuals like Jacob Barnet, who was arrested and exiled.

Jewish Resettlement (16th–19th Centuries)

Henry VIII and Jewish Culture

During his rule, Henry VIII became interested in Judaism. When he tried to end his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, his representatives talked with important Italian Jews. He even tried to use laws from the Old Testament to justify his annulment. Later, in 1524, Hebrew was first printed in England, and in 1549, people were allowed to use Hebrew in private worship.

Hidden Jewish People in England

Starting in the 1500s, after the Spanish Inquisition, some Jewish people began to return to England. Even though they had to hide their religion, many became known as Jews. Many hidden Jews became famous in England. One Marrano (a Jew who pretended to be Christian) from Spain, Hector Nunes, was important in English spying. He sent information from Spain to Queen Elizabeth's spymaster, Sir Francis Walsingham, using his merchant ships. This information helped England defeat the Spanish Armada in 1588. Another Jew, Joachim Gaunse from Bohemia, came to England as a metal expert to help defeat Spain. Because of his work, Sir Walter Raleigh invited Gaunse to sail with him to North America. He became the first Jew to set foot on North American soil.

Another Marrano gained attention for less positive reasons. Roderigo Lopez, Queen Elizabeth I's personal doctor, was bribed by the Spanish king to poison the Queen. He was executed when the plan was discovered. This caused a wave of anti-Jewish feeling in England, the first since the expulsion. After his trial, famous plays like William Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice and Christopher Marlowe's The Jew of Malta were written, both showing Jews in negative ways.

By the mid-1600s, many Marrano merchants settled in London and formed a secret community. They did a lot of business with places like the Levant (Middle East), East and West Indies, and Brazil.

Francis Drake's quartermaster during his trip around the world was named "Moses the Jew." There is also proof of Jews living in Plymouth in the 1600s.

Official Resettlement in 1655

Before their official return, a growing positive feeling towards Jews, called philo-Semitism, made England a more welcoming place. After the English Reformation, Anglicans (members of the Church of England) started to see their practices as more similar to Jewish ones than Catholic ones. In 1607, Cambridge University got its first rabbi to teach Hebrew. Many students then helped translate the King James Bible. This translation started to make biblical names sound more Hebrew. For example, Elias became Elijah. Many Puritans loved these Old Testament names, and Puritan children were often given new Hebrew spellings. Puritans also adopted Jewish practices like strict observation of the Sabbath. When they criticized Anglican practices for being too Catholic, Richard Hooker, a famous Anglican theologian, cleverly linked these practices to Jewish ones to quiet the Puritans. By the 1600s, Englishmen like Edwin Sandys and Laurence Aldersey became interested in Jewish culture, visiting Jewish neighborhoods and synagogues. Oliver Cromwell believed the English were one of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, and so deserved the blessings promised in the Old Testament. Under his rule after the English Civil War, philo-Semitism grew, making it the right time for Jews to propose their official return.

In the 1650s, Menasseh Ben Israel, a rabbi and leader of the Dutch Jewish community, asked Cromwell to allow Jews back into England. Cromwell agreed. Although he couldn't force a council in December 1655 to formally agree, he made it clear that the ban on Jews would no longer be enforced. In 1655–56, there was a big debate about allowing Jews back. The issue divided religious radicals and more traditional people. The Puritan William Prynne was strongly against it, while the Quaker Margaret Fell was passionately in favor. In the end, Jews were allowed back in 1655. By 1690, about 400 Jews had settled in England. A sign of this progress was when William III of England knighted Solomon de Medina in 1700, the first Jew to receive such an honor.

The 1700s

Jewish Naturalization Act of 1753

The Jewish Naturalisation Act was approved by George II on July 7, 1753. However, it was cancelled in 1754 because many people opposed it.

During the Jacobite rising of 1745, Jews showed great loyalty to the government. Their main financier, Samson Gideon, helped strengthen the stock market. Several young Jewish men volunteered to defend London. Perhaps as a reward, Henry Pelham introduced the Jew Bill of 1753, which allowed Jews to become naturalized citizens by applying to Parliament. It passed the Lords easily, but in the House of Commons, the Tories strongly protested, calling it an "abandonment of Christianity." However, the Whigs pushed for it as part of their policy of religious toleration, and the bill passed.

In 1798, Nathan Mayer von Rothschild started a business in Manchester, and later the N M Rothschild & Sons bank in London. He was sent to the UK by his father Mayer Amschel Rothschild. This bank helped fund Wellington in the Napoleonic Wars. It also financed the British government's purchase of Egypt's share in the Suez Canal in 1875 and supported Cecil Rhodes in developing the British South Africa Company. Beyond banking, members of the Rothschild family in UK became famous academics, scientists, and gardeners.

Some English ports, like Hull, began to receive Jewish immigrants and traders, known as "port Jews," around 1750.

Jewish Rights and Prosperity (19th Century)

With Catholic Emancipation in 1829 (when Catholics gained more rights), Jews hoped for similar changes. The first step for them came in 1830 when a petition signed by 2,000 merchants from Liverpool was presented to Parliament. This was followed by a bill that would be debated for the next thirty years.

In 1837, Queen Victoria knighted Moses Haim Montefiore. Four years later, Isaac Lyon Goldsmid became the first Jew to receive a hereditary title (baronet). The first Jewish Lord Mayor of London, Sir David Salomons, was elected in 1855. Then, in 1858, Jews gained full rights. On July 26, 1858, Lionel de Rothschild was finally allowed to sit in the British House of Commons when the law requiring a Christian oath of office was changed. Benjamin Disraeli, who was born to Jewish parents but baptized as a Christian, was already an MP. In 1868, Disraeli became Prime Minister. In 1884, Nathan Mayer Rothschild, 1st Baron Rothschild became the first Jewish member of the British House of Lords.

By 1880, the thriving Jewish community in Birmingham was centered around its synagogue. Men worked together to protect the community's reputation and interests. Funerals and burials brought together rich and poor, men and women. Marriage outside the community was rare. However, when Jews from Eastern Europe arrived after 1880, it caused a split between the older, more English, middle-class Jews and the generally poorer new immigrants who spoke Yiddish.

By 1882, 46,000 Jews lived in England. By 1890, Jews had full rights in all areas of life. Since 1858, Parliament has always had Jewish members. At this time, many Jews from the East End moved to wealthier parts of East London like Hackney or to North London areas like Stoke Newington.

Synagogues were built openly across the country. Some were large and grand buildings in styles like classical, Romanesque, or Victorian Gothic, such as Singers Hill Synagogue in Birmingham.

All Jewish Rifle Volunteer Corps (1861)

In 1857, fears of invasion led to the creation of the Volunteer Force, which included rifle units. These units were formed by local communities with permission from their local leader.

The leader of the Tower Hamlets area (which was larger than the modern borough) gave permission for Jews from East London to form the East Metropolitan Rifle Volunteers (11th Tower Hamlets).

The Jewish Chronicle reported on the 165 Jewish volunteers, marching with music, calling it "a sight never before seen in Britain."

Like most Volunteer Force units, the East Metropolitan Rifle Volunteers existed for only a short time before joining other units. But their creation caused a discussion in the Jewish community about whether separate or mixed military units were better.

Modern Times

From the 1880s to 1920

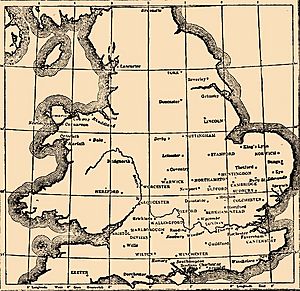

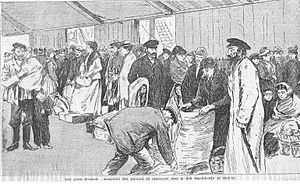

From the 1880s into the early 1900s, terrible attacks (called pogroms) and harsh laws in Russia forced many Jews to leave their homes. Of the Jewish people who left Eastern Europe, 1.9 million (80%) went to the United States, and 140,000 (7%) came to Britain. Many came through "chain migration," where the first successful family members sent money or tickets to help others follow. These Ashkenazi Jews traveled by train across Europe to ports on the North Sea and Baltic, entering England through London, Hull, Grimsby, and Newcastle. The Jewish communities in these northern ports grew with both temporary visitors and those heading to New York, Buenos Aires, or other British cities.

In 1917, Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild helped set the stage for the Balfour Declaration. This declaration promised a homeland in Palestine for Jews in a new Zionist State.

The Jewish population in England grew from 46,000 in 1880 to about 250,000 in 1919. They mostly lived in big industrial cities, especially London, Manchester, and Leeds. In London, many Jews lived near the docks in Spitalfields and Whitechapel, making the East End known as a Jewish neighborhood. Unlike many Jewish communities in Poland, Jews in England generally wanted to fit into wider English culture. They started Yiddish and Hebrew newspapers and youth groups like the Jewish Lads' Brigade. Immigration was eventually limited by the Aliens Act 1905, after pressure from groups like the British Brothers' League. This law was followed by the Aliens Restriction (Amendment) Act 1919.

Marconi Scandal (1912–1913)

The Marconi scandal brought antisemitism into politics. It was claimed that senior ministers in the Liberal government secretly profited from knowing about deals related to wireless telegraphy. Some of the main people involved were Jewish.

First World War

About 50,000 Jews served in the British Armed Forces during World War I, and around 10,000 died. Britain's first all-Jewish regiment, the Jewish Legion, fought in Palestine. An important result of the war was Britain taking control of the Palestinian Mandate and the Balfour Declaration. This was an agreement between the British Government and the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland to work towards creating a homeland for Jews in Palestine.

Entrepreneurs

Jews from Eastern Europe had a long history as skilled business people. They were more likely to start their own businesses than their non-Jewish neighbors, especially in the clothing industry, retail, entertainment, and real estate. London offered great chances for business owners.

Sports

Antisemitism was a big problem for British Jews, especially the common idea that Jews were weak or cowardly. The Zionist writer Max Nordau used the term "muscle Jew" to fight this stereotype. Challenging this idea was a key reason for serving in the Boer War and the First World War. It also motivated participation in sports that appealed to working-class Jewish youth.

From the 1890s to the 1950s, British boxing was dominated by Jews whose families had moved from Russia or the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Jews were very involved in boxing as fighters, managers, and fans. Their high visibility in a popular sport helped reduce antisemitism and made them more accepted in British society. The Jewish community worked hard to encourage boxing among young people, as a way to help them adopt British character traits and cultural values. Young people eagerly took part, though interest sharply declined after World War II as they moved into the middle class.

The most famous Jewish athlete in Britain was Harold Abrahams (1899–1978). He became famous from the film Chariots of Fire for winning the gold medal in the 100-meter sprint at the 1924 Paris Olympics. Abrahams was very English in his culture, and his fitting into society went hand-in-hand with his sports achievements. He became a hero to the British Jewish community.

Before and During World War II

While antisemitism grew in the 1930s, there was also strong support for British Jews in their local communities. This led to events like the Battle of Cable Street, where socialists, trade union members, Jews, and their neighbors strongly resisted antisemitism and fascism. They successfully stopped a British Union of Fascists rally from going through a heavily Jewish area, despite police efforts.

Britain's history was complex, and it wasn't very welcoming to Jewish refugees fleeing the Nazi regime in Germany and other fascist states in Europe. About 40,000 Jews from Austria and Germany were eventually allowed to settle in Britain before the War, along with 50,000 Jews from Italy, Poland, and other parts of Eastern Europe. Despite increasingly serious warnings from Germany, Britain refused at the 1938 Evian Conference to allow more Jewish refugees into the country. The main exception allowed by Parliament was the Kindertransport. This was an effort just before the war to bring Jewish children (their parents were not given visas) from Germany to Britain. Around 10,000 children were saved by the Kindertransport.

During the Nazi occupation of the Channel Islands, three Jewish women from Guernsey—Marianne Grunfeld, Therese Steiner, and Auguste Spitz—were sent to Saint-Malo, Nazi-occupied France, and eventually killed at Auschwitz concentration camp. They were the only Jews deported from British soil and killed in the Holocaust.

When war was declared, 74,000 German, Austrian, and Italian citizens in the UK were held as enemy aliens. After individual reviews, most, who were largely Jewish and other refugees, were released within six months.

Even more important to many Jews was the permission to settle in Mandatory Palestine, which was controlled by Britain. To try to keep peace between Jewish and Arab populations, especially after the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, Britain strictly limited immigration. This limit became almost absolute after the White Paper of 1939 nearly stopped all legal immigration. During the War, Zionists organized an illegal immigration effort, led by "Hamossad Le'aliyah Bet" (the group that later became the Mossad). They rescued tens of thousands of European Jews from the Nazis by shipping them to Palestine in old boats. Many of these boats were stopped, and some sank with great loss of life. The efforts began in 1939. The last immigrant boat to try to enter Palestine before the end of the war was the MV Struma, which was sunk by a Soviet Navy submarine in February 1942, leading to the loss of nearly 800 lives.

Many Jews joined the British Armed Forces, including about 30,000 Jewish volunteers from Palestine alone. Some of these fought in the Jewish Brigade. Many formed the core of the Haganah (a Jewish paramilitary organization) after the war.

By July 1945, 228,000 troops of the Polish Armed Forces in the West, including Polish Jews, were serving under the British Army's command. Many of these men and women were originally from eastern Poland and had been sent to Siberia by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin from 1939–1941. They were then released from the Soviet Gulags to form the Anders Army and marched to Iran to form the II Corps (Poland). The Polish II Corps then moved to the British Mandate of Palestine, where many Polish Jews, including Menachem Begin, left the army to help create the state of Israel. Other Polish Jews stayed in the Polish Army to fight with the British in North Africa and Italy. Around 10,000 Polish Jews fought under the Polish flag and British command at the Battle of Monte Cassino. All of them were allowed to settle in the UK after the Polish Resettlement Act 1947, Britain's first major immigration law.

|

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |