Cecil Rhodes facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Cecil Rhodes

|

|

|---|---|

Rhodes, c. 1900

|

|

| 7th Prime Minister of the Cape Colony | |

| In office 17 July 1890 – 12 January 1896 |

|

| Monarch | Queen Victoria |

| Governor | Henry Loch Sir William Gordon Cameron Hercules Robinson |

| Preceded by | John Gordon Sprigg |

| Succeeded by | John Gordon Sprigg |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Cecil John Rhodes

5 July 1853 Bishop's Stortford, Hertfordshire, England |

| Died | 26 March 1902 (aged 48) Muizenberg, Cape Colony (now South Africa) |

| Citizenship | United Kingdom |

| Relations | Reverend Francis William Rhodes (father) Louisa Peacock Rhodes (mother) Frank Rhodes (brother) |

| Alma mater | Oriel College, Oxford |

| Occupation | Businessman Politician |

Cecil Rhodes (born July 5, 1853, died March 26, 1902) was a powerful businessman and politician from England. He spent most of his life in South Africa. His father was a church leader. Rhodes went to grammar school in England. When he was 16, he moved to the British colony of Natal in South Africa because he was not well. In South Africa, he started working in diamond mining. He later studied at Oxford University in England.

Rhodes founded the territory known as Rhodesia. He also started the British South Africa Company. This company controlled large areas in South Africa, which later became Southern Rhodesia and Northern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe and Zambia). He even became the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. He worked with a group called the Afrikaner Bond. But he lost their support when he backed a rebellion in 1895. This led to his resignation. In British politics, he supported the Liberal Party. Rhodes also created the famous Rhodes Scholarship. This scholarship helps students study at Oxford University. He was also a member of the Freemasons.

Contents

Early Life

Growing Up in England

Cecil Rhodes was born in Bishop's Stortford, England, in 1853. He was the fifth son of Reverend Francis William Rhodes and Louisa Peacock Rhodes. His father was a Church of England clergyman. He was known for giving short sermons. Cecil's brother, Frank Rhodes, became an army officer.

Rhodes attended Bishop's Stortford Grammar School from age nine. However, he was often sick with asthma. Because of his poor health, he left grammar school in 1869. His family worried he might have tuberculosis, a serious lung disease. His father decided to send him to South Africa. They believed the sea voyage and warmer climate would improve his health.

Starting in South Africa

When Rhodes first arrived in Africa, his aunt Sophia lent him money. He briefly stayed with Dr. P.C. Sutherland in Pietermaritzburg. Rhodes then became interested in farming. He joined his brother Herbert on a cotton farm in the Umkomazi valley. But the land was not good for cotton, and the farm failed.

In October 1871, 18-year-old Rhodes and his 26-year-old brother Herbert moved. They went to the diamond fields of Kimberley. With money from N M Rothschild & Sons, Rhodes began buying smaller diamond mines. Over the next 17 years, he bought almost all of them in the Kimberley area. In 1873, he went back to Britain to study at Oxford. However, he only stayed for one term before returning to South Africa.

By 1890, Rhodes controlled most of the world's diamond supply. He partnered with the London-based Diamond Syndicate. They worked together to control the supply and keep prices high. Rhodes also helped manage his brother's mining claims. Early partners included John X. Merriman and Charles Rudd. Rudd later became his partner in the De Beers Mining Company.

His University Education

In 1873, Rhodes left his farm to his business partner, Rudd. He sailed to England to attend university. He was accepted into Oriel College, Oxford. He only completed one term in 1873. He then returned to South Africa. He did not go back to Oxford until 1876. He was greatly inspired by a lecture from John Ruskin at Oxford. This lecture strengthened his belief in British imperialism.

At Oxford, Rhodes became friends with James Rochfort Maguire and Charles Metcalfe. Maguire later became a director of the British South Africa Company. Rhodes admired the Oxford university system. He was inspired to create his scholarship program. He believed Oxford graduates were leaders in many fields.

While at Oriel College, Rhodes joined the Freemasons. He was part of the Apollo University Lodge. Although he initially had doubts, he remained a South African Freemason until his death. He later imagined creating his own secret society. Its goal was to bring the entire world under British rule.

Diamonds and De Beers

While Rhodes was studying at Oxford, his diamond business in Kimberley grew. Before he left for Oxford, he and C.D. Rudd invested in new mining claims. These were known as old De Beers (Vooruitzicht). The land was named after Johannes Nicolaas de Beer and his brother. They had owned the farm.

In 1874 and 1875, the diamond fields faced a tough time. But Rhodes and Rudd stayed and bought more interests. They believed many diamonds were hidden deep in the hard "blue ground." This was below the softer yellow layer. During this time, mines often flooded with water. Rhodes and Rudd got the job of pumping water out of the three main mines. After his first term at Oxford, Rhodes lived with Robert Dundas Graham. Graham later became a mining partner with Rudd and Rhodes.

On March 13, 1888, Rhodes and Rudd officially started De Beers Consolidated Mines. They combined many smaller claims into one big company. Rhodes was the secretary of the company, which started with £200,000. This made it the largest owner in the mine. Rhodes became the chairman of De Beers when it was founded in 1888. N M Rothschild & Sons Limited provided the funding for De Beers in 1887.

Founding Rhodesia

The British South Africa Company (BSAC) had its own police force. This force was called the British South Africa Police. They used it to control Matabeleland and Mashonaland. These areas are now part of Zimbabwe. The company hoped to find a "new Rand" (a rich gold area) from old gold mines. These mines belonged to the Shona. But the gold was not as plentiful. So, many white settlers became farmers instead of miners.

The Ndebele and the Shona were two main groups. They both rebelled against the European settlers. The BSAC defeated them in the First Matabele War and Second Matabele War. After hearing that the Ndebele spiritual leader, Mlimo, was killed, Rhodes did something brave. He walked unarmed into the Ndebele stronghold in Matobo Hills. He convinced the Impi (warriors) to stop fighting. This ended the Second Matabele War.

By the end of 1894, the BSAC controlled a huge area. This land was called "Zambesia" after the Zambezi River. It covered 1,143,000 square kilometers. In May 1895, its name was officially changed to "Rhodesia." This showed Rhodes's popularity among the settlers. They had been using the name since 1891. The southern part became Southern Rhodesia in 1898 (now Zimbabwe). The northern parts became North-Western and North-Eastern Rhodesia (later Northern Rhodesia, then Zambia).

Rhodes stated in his will that he wanted to be buried in Matobo Hills. After he died in the Cape in 1902, his body was taken by train to Bulawayo. Ndebele chiefs attended his burial. They asked that no rifles be fired, so as not to disturb the spirits. They then gave a white man the Matabele royal salute, Bayete, for the first time.

Rhodes is buried with Leander Starr Jameson and 34 British soldiers. These soldiers died in the Shangani Patrol. Even though some want his body moved to the United Kingdom, his grave remains there. It is "part and parcel of the history of Zimbabwe." Thousands of visitors come to his grave each year.

His Political Ideas

Rhodes wanted to make the British Empire bigger. He believed that the Anglo-Saxon people were meant to be great.

Rhodes wanted the British Empire to be a superpower. He imagined all British-controlled countries, like Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the Cape Colony, having a say in the British Parliament. He even made American students eligible for the Rhodes scholarships. He hoped to create American leaders who would want the United States to rejoin the British Empire.

People have different opinions about Rhodes's views on race. Some critics call him an "architect of apartheid" and a "white supremacist." These criticisms became stronger around 2015.

In British politics, Rhodes supported the Liberal Party. His biggest impact was his strong support for the Irish nationalist party. This party was led by Charles Stewart Parnell.

Rhodes worked well with the Afrikaners in the Cape Colony. He supported teaching both Dutch and English in public schools.

Death and Legacy

Rhodes was a key figure in southern African politics. But he had poor health throughout his life.

He was sent to Natal at age 16 because of heart problems. When he returned to England in 1872, his health worsened. His doctor thought he would only live six more months. He went back to Kimberley, where his health improved.

From age 40, his heart condition became more severe. He died from heart failure in 1902, at age 48. He passed away at his seaside cottage in Muizenberg.

The government arranged a long train journey for his funeral. The train stopped at every station from the Cape to Rhodesia. This allowed people to pay their respects. He was finally buried at World's View. This is a hilltop about 35 kilometers (22 miles) south of Bulawayo, in what was then Rhodesia. Today, his grave is part of Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe.

In 2004, he was voted 56th in the South African TV series Great South Africans.

When he died, he was considered one of the richest men in the world. In his first will, written in 1877, Rhodes wanted to create a secret society. Its goal was to bring the whole world under British rule.

Rhodes's final will left a large piece of land near Table Mountain to South Africa. Part of this land became the University of Cape Town. Another part became the Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden. Much of it was saved from building and is now an important nature area.

Rhodes Scholarship

In his last will, Rhodes set up the Rhodes Scholarship. This was the world's first international study program. The scholarship allowed students from British territories and Germany to study at Oxford University. Rhodes wanted to encourage leadership with public spirit and good character. He also hoped to "make war impossible" by promoting friendship between powerful nations.

Memorials to Rhodes

The Rhodes Memorial stands on Rhodes's favorite spot. It is on the slopes of Devil's Peak in Cape Town. From there, you can see north and east towards the Cape to Cairo route. From 1910 to 1984, Rhodes's house in Cape Town, Groote Schuur, was the official home for South African Prime Ministers. It was also used by presidents P. W. Botha and F. W. De Klerk.

His birthplace became the Rhodes Memorial Museum in 1938. It is now called Bishops Stortford Museum. The cottage in Muizenberg where he died is a special heritage site. Today, it is a museum run by the Muizenberg Historical Conservation Society. Visitors can see many items related to Rhodes. This includes the original De Beers board room table.

Rhodes University, in Grahamstown, was named after him. It was founded by an Act of Parliament on May 31, 1904.

The people of Kimberley built a memorial for Rhodes. It was unveiled in 1907. The large bronze statue shows Rhodes on his horse. He is looking north with a map, dressed as he was when he met the Ndebele after their rebellion.

Opposition to Memorials

People have opposed memorials to Rhodes since the 1950s. At that time, some students wanted a Rhodes statue removed from the University of Cape Town. In 2015, a movement called "Rhodes Must Fall" started. Student protests at the University of Cape Town successfully led to the removal of the Rhodes statue from campus. This protest also aimed to highlight the lack of change in South African institutions after apartheid.

After protests and vandalism at the University of Cape Town, similar movements began. These movements are against Cecil Rhodes memorials in South Africa and other countries. They include a campaign to change the name of Rhodes University. They also want to remove a statue of Rhodes from Oriel College, Oxford. A documentary called The Battle for Britain's Heroes covered this campaign.

In 2020, during worldwide protests after the killing of George Floyd, thousands of people called for the statue of Cecil Rhodes to be removed from Oxford University. Protesters chanted "Take it down" and "Decolonise." They held signs saying "Rhodes Must Fall" and "Black Lives Matter." However, Oxford University decided to keep the Rhodes statue. Oriel College stated they would lose about £100 million in donations if they removed it.

Images for kids

-

French drawing of Rhodes. It shows him trapped in Kimberley during the Second Boer War. He is peering from a tower with papers.

-

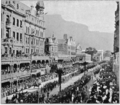

Funeral procession of Rhodes in Adderley Street, Cape Town, on April 3, 1902

See also

In Spanish: Cecil Rhodes para niños

In Spanish: Cecil Rhodes para niños