Charles Stewart Parnell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Charles Stewart Parnell

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party | |

| In office 11 May 1882 – 26 November 1891 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | John Redmond |

| Leader of the Home Rule League | |

| In office 16 April 1880 – 11 May 1882 |

|

| Preceded by | William Shaw |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Member of Parliament for Cork City |

|

| In office 5 April 1880 – 6 October 1891 |

|

| Preceded by | Nicholas Daniel Murphy |

| Succeeded by | Martin Flavin |

| Member of Parliament for Meath |

|

| In office 21 April 1875 – 5 April 1880 |

|

| Preceded by | John Martin |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Martin Sullivan |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Charles Stewart Parnell

27 June 1846 Avondale, County Wicklow, Ireland |

| Died | 6 October 1891 (aged 45) Hove, East Sussex, England |

| Cause of death | Pneumonia |

| Resting place | Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin, Ireland |

| Political party | Irish Parliamentary Party (1882–1891) Home Rule League (1880–1882) |

| Spouses | Katharine O'Shea (m. 1891; d. 1921) |

| Relations |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | Magdalene College, Cambridge |

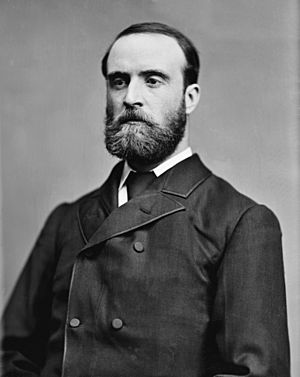

Charles Stewart Parnell (born June 27, 1846 – died October 6, 1891) was an important Irish nationalist politician. He was a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1875 to 1891. He led the Home Rule League from 1880 to 1882 and then the Irish Parliamentary Party from 1882 to 1891. His party was very powerful in the House of Commons during debates about Home Rule in the mid-1880s.

Parnell came from a wealthy Irish family with English roots who owned land. He was a Protestant in County Wicklow. He worked to change land laws and started the Irish National Land League in 1879. He became the leader of the Home Rule League, which worked on its own, separate from the main British parties. He became very influential by balancing different political ideas and using parliament's rules cleverly.

He was put in Kilmainham Gaol prison in Dublin in 1882. He was let out after he agreed to stop supporting violent actions outside of parliament. That same year, he changed the Home Rule League into the Irish Parliamentary Party. He controlled this party very closely, making it Britain's first well-organized political party.

In the 1885 election, no single party won enough seats to have full control. This meant Parnell's party held the "balance of power." They could decide which party would lead the government. His power helped convince William Gladstone's Liberal Party to make Home Rule their main goal. Parnell's reputation was at its highest from 1889 to 1890. This was after letters published in The Times newspaper, which falsely linked him to the Phoenix Park killings of 1882, were proven to be fake. However, his party split in 1890 due to a personal challenge. He led a small group of supporters until he died in 1891.

Parnell is remembered as the best organizer of an Irish political party of his time. He was one of the most powerful figures in parliamentary history. Even with his great political talent, his career faced a personal challenge that he could not fully recover from. He was never able to achieve his main goal of getting Home Rule for Ireland during his lifetime.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Charles Stewart Parnell was born at Avondale House, in County Wicklow, Ireland. He was the seventh of eleven children. His father, John Henry Parnell, was a wealthy landowner. His mother, Delia Tudor Stewart, was American. Her father was Admiral Charles Stewart (1778-1869), a hero of the American navy. Parnell's family had many important connections. They were linked to old Irish politics and to the American War of Independence.

The Parnell family came from England in the 1600s. They had many famous members, including a poet and a politician. Charles's grandfather, William Parnell, was also an MP for Wicklow. So, Charles Stewart Parnell had many ties to different parts of society. He was part of the Church of Ireland, which was the official church at the time. Yet, he became famous as a leader of Irish nationalism.

Parnell's parents separated when he was six years old. He went to different schools in England and had a difficult childhood. When his father died in 1859, Charles inherited the Avondale estate. He studied at Magdalene College, Cambridge from 1865 to 1869. However, he often had to be away because of money problems with his estate. He never finished his degree. In 1871, he traveled through the United States with his older brother, John Howard Parnell.

In 1874, he became the High Sheriff of Wicklow, which was a local official role. He was known for improving his land and helping to bring industry to south Wicklow. He became interested in the Home Rule League. This group was formed in 1873 by Isaac Butt. It wanted Ireland to have some self-government. Parnell tried to run for election in Wicklow to support this movement. But as high sheriff, he was not allowed to. He tried again in 1874 in County Dublin but did not win. Some historians believe Parnell joined the Irish cause because he strongly disliked England. This feeling might have come from his school days or his mother's views.

Political Beginnings

On April 17, 1875, Parnell was first elected to the House of Commons. He won a special election for Meath. He was a Home Rule League MP. He replaced John Martin, an older politician who had died. Later, Parnell represented Cork City from 1880 to 1891.

During his first year as an MP, Parnell mostly watched how parliament worked. He first gained public attention in 1876. He said in the House of Commons that he did not believe Fenian members had committed murder in Manchester. This caught the attention of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). The IRB was an Irish group that wanted independence, sometimes using force. Parnell worked to gain support from Fenian groups in Britain and Ireland. He joined the more radical part of the Home Rule League.

Parnell and others used a tactic called obstructionism. This meant using parliament's rules to slow down its work. They gave long speeches that were not always on topic. Their goal was to make the House of Commons pay more attention to Irish issues. The leader of the Home Rule League, Isaac Butt, did not like this tactic.

Parnell visited the United States in 1877. It is debated whether he ever officially joined the IRB. However, he became president of the Home Rule Confederation of Great Britain in August 1877. This happened after Butt was removed from the role. Parnell was a quiet speaker in parliament. But his skills in organizing, analyzing, and planning were highly praised. This helped him become the leader of the British organization. When Isaac Butt died in 1879, Parnell became the leader of the Home Rule League Party.

New Ideas for Ireland

From 1877, Parnell met privately with important Fenian leaders. He met John Devoy, a strong leader of the American-Irish group Clan na Gael. In 1878, Devoy offered Parnell a "New Departure" deal. This deal suggested that peaceful political action and more forceful actions could work together for Irish self-government. It had conditions, like focusing on farmers owning their land and resisting unfair laws.

Parnell preferred to keep his options open. He spoke to farmer groups in 1879. He began to understand how powerful the land reform movement could be. He worked with Michael Davitt, who was impressed by Parnell. Parnell then took on the role of leader for this "New Departure." He held many public meetings across the country.

Leading the Land League

Parnell was chosen as president of Davitt's new Irish National Land League in Dublin on October 21, 1879. He signed a strong statement for the Land League, pushing for land reform. By doing this, he connected the large public movement with political action in parliament. This had big effects on both.

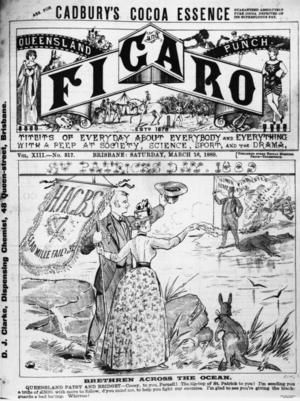

He traveled to America in December 1879 with John Dillon. They wanted to raise money for famine relief and support for Home Rule. They collected £70,000 to help people in Ireland. During his successful trip, Parnell met American President Rutherford B. Hayes. On February 2, 1880, he spoke to the United States House of Representatives about Ireland. He spoke in 62 cities in the United States and Canada. He was so popular in Toronto that people called him "the uncrowned king of Ireland." He tried to keep Fenian support but said he could not join a secret group himself. He often used unclear language in his speeches, letting people interpret his words in different ways.

His trip ended suddenly when a general election was announced for April 1880. He returned to Ireland to run. The Conservatives lost to the Liberal Party. William Gladstone became Prime Minister again. Sixty-three Home Rule politicians were elected. Twenty-seven of them supported Parnell. Parnell won three seats: Cork City, Mayo, and Meath. He chose to represent Cork. His success helped him become the leader of the new Home Rule League Party in May. Ireland was on the edge of a "land war" at this time.

Even though the Land League discouraged violence, attacks on farms increased. Parnell saw that he needed to replace violence with large public meetings. He also used Davitt's idea of a boycott. This was a way to achieve his goal of self-government. Gladstone was worried about the Land League's power in late 1880. He tried to solve the land problem with the Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881. This law created a Land Commission that lowered rents. It also allowed some farmers to buy their land. This stopped unfair evictions, but not if rent was unpaid.

Historian R. F. Foster says that in the countryside, the Land League helped make Catholic Irish people more politically aware. It did this by showing their identity against landlords and English ways.

The Kilmainham Agreement

Parnell's own newspaper, United Ireland, criticized the Land Act. He was arrested on October 13, 1881. Many of his party members, like William O'Brien and John Dillon, were also arrested. They were put in Kilmainham Gaol under a special law. They were accused of "sabotaging the Land Act." From prison, Parnell and others signed the No Rent Manifesto. This paper called for farmers across the country to stop paying rent. The Land League was quickly shut down.

While in prison, Parnell made a deal with the government in April 1882. This deal was worked out through MP William O'Shea. Parnell agreed that if the government helped 100,000 tenants with their unpaid rents, he would withdraw the manifesto. He also promised to work against farm-related crime. He realized that violence would not win Home Rule. He also promised to work well with the Liberal Party in the future.

His release on May 2, after what was called the Kilmainham Treaty, was a key moment for Parnell's leadership. He returned to working within parliament and constitutional politics. This made him lose some support from American-Irish groups. His political skill helped save the Home Rule movement. This was especially important after the Phoenix Park killings on May 6. In this event, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, Lord Frederick Cavendish, and his assistant, T. H. Burke, were murdered in Dublin. Parnell was so shocked that he offered to resign as an MP. The group responsible, the Invincibles, fled to the United States. This allowed Parnell to cut ties with radical Land League members. In the end, this led to Parnell and Gladstone working closely together. Many members left the IRB and joined the Home Rule movement. For the next 20 years, the IRB was not a major force in Irish politics. Parnell and his party became the main leaders of the nationalist movement in Ireland.

Building a Stronger Party

Parnell now wanted to use his experience and huge support to push for Home Rule. On October 17, 1882, he brought back the Land League as the Irish National League (INL). This new group combined moderate ideas about land, a Home Rule plan, and election work. It was organized like a pyramid, with Parnell having great power and direct control over parliament. Working within parliament was now the future path. The INL and the Catholic Church formed an informal alliance. This was a main reason why the Home Rule cause became strong again after 1882. Parnell knew that the Catholic Church's support was vital for his success. He worked closely with Catholic leaders to gain control over Irish voters. Church leaders mostly saw Parnell's party as protectors of church interests. By the end of 1885, the INL had 1,200 branches across the country. Parnell left the daily running of the INL to his assistants. Its continued work for farmers led to new Irish Land Acts. These laws changed Irish land ownership over three decades. They replaced large estates owned by wealthy families with land owned by farmers.

Parnell then focused on the Home Rule League Party. He remained its leader for over ten years. He spent most of his time in Westminster, the British parliament. He completely changed the party. He copied the INL's structure within it. He created a well-organized system at the local level. He introduced membership to replace informal groups. Before, MPs often voted differently or did not attend parliament. Parnell made sure party members voted together.

In 1882, he changed his party's name to the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP). A key part of Parnell's changes was a new way to choose candidates. This made sure that professional candidates who would take their seats were chosen. In 1884, he made a strict 'party pledge'. This forced party MPs to vote as a group in parliament every time. Creating a strong party system and official structure was new in politics then. The Irish Parliamentary Party is often seen as the first modern British political party. Its efficient structure and control were very different from the loose rules of other British parties. These other parties later started to copy Parnell's model. The Representation of the People Act 1884 allowed more people to vote. The IPP increased its number of MPs from 63 to 85 in the 1885 election.

These changes affected the types of candidates chosen. Under the previous leader, Isaac Butt, the party's MPs were a mix of Catholics and Protestants, landlords and others. They came from different political backgrounds. This often led to disagreements and split votes. Under Parnell, fewer Protestant and landlord MPs were elected. The party became much more Catholic and middle-class. Many journalists and lawyers were elected. Wealthy landowners and Conservatives disappeared from the party.

Pushing for Home Rule

Parnell's party quickly became a well-organized and energetic group of politicians. By 1885, he was leading a party ready for the next election. His statements on Home Rule were designed to get the most support possible.

Both British parties considered different ideas for Ireland to have more self-government. In March 1885, the British government rejected a plan for local councils in Ireland. Gladstone, the Liberal leader, said he was willing to go "rather further" than that idea. After Gladstone's government fell in June 1885, Parnell told Irish voters in Britain to vote against the Liberal Party. The November general elections resulted in a "hung Parliament." The Liberals won 335 seats, 86 more than the Conservatives. But Parnell's group of 86 Irish Home Rule MPs held the balance of power. Parnell's goal was now to get parliament to accept the idea of a Dublin parliament for Ireland.

Parnell first supported a Conservative government. But when farm prices fell and unrest grew in 1885, the Conservative government announced strict new laws in January 1886. Parnell then switched his support to the Liberals. This shocked Unionists, who wanted Ireland to remain part of the UK. The Orange Order, a group that opposed the Land League, now openly opposed Home Rule. On January 20, the Irish Unionist Party was formed in Dublin. By January 28, the Conservative government had resigned.

The Liberal Party regained power on February 1. Their leader, Gladstone, was moving towards Home Rule. He was influenced by countries like Norway, which was self-governing but part of Sweden. Gladstone's son publicly hinted at this plan. Gladstone's new government prepared to respond generously to Irish demands. However, he could not get support from some key members of his own party. Some resigned when they saw the terms of the proposed bill.

On April 8, 1886, Gladstone introduced the First Irish Home Rule Bill. Its goal was to create an Irish parliament. But important issues like defense would remain with the British parliament. The Conservatives now strongly supported keeping the Union. The bill was defeated in June by 341 to 311 votes.

Parliament was dissolved, and new elections were called. Irish Home Rule was the main issue. Gladstone hoped to win a big victory like he did in 1868. But the July 1886 general election was a defeat for the Liberals. The Conservatives and the Liberal Unionist Party won a majority. They had 118 more seats than the combined Gladstonian Liberals and Parnell's 85 Irish Party seats. The Conservative leader, Lord Salisbury, formed his second government. It was a minority Conservative government with support from the Liberal Unionists.

The split in the Liberal Party made the Unionists the main power in British politics until 1906. They had strong support in many English cities. A second Home Rule Bill would pass the House of Commons in 1893. But it was overwhelmingly defeated in the House of Lords.

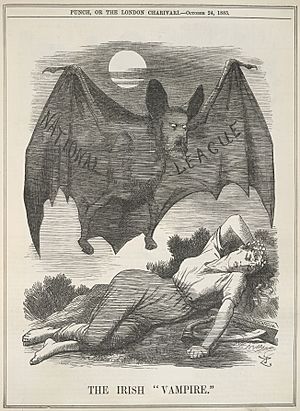

The Pigott Forgeries

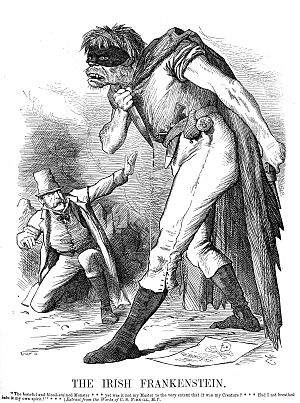

Parnell became the center of public attention again in March and April 1887. The British newspaper The Times accused him of supporting the Phoenix Park killings in May 1882. These were the murders of the new Chief Secretary for Ireland, Lord Frederick Cavendish, and his assistant, Thomas Henry Burke, in Dublin. The newspaper also accused his movement of being involved in other crimes. Letters were published that suggested Parnell was involved in the murders.

A special Commission of Enquiry was set up, which Parnell had asked for. In February 1889, after 128 meetings, the commission revealed that the letters were fake. They had been created by Richard Pigott, a dishonest journalist who disliked Parnell. Pigott broke down during questioning when his spelling mistakes proved the letter was a forgery. He fled to Madrid and later died. Parnell was proven innocent, which disappointed the Conservatives and Prime Minister Salisbury.

The commission's report, published in February 1890, did not clear Parnell's movement of all criminal involvement. Parnell then sued The Times newspaper. The newspaper paid him £5,000 in an out-of-court settlement. When Parnell entered the House of Commons on March 1, 1890, after being cleared, he received a hero's welcome. Gladstone led the applause from his fellow MPs. This had been a dangerous time in his career. Yet, Parnell remained calm and undisturbed, which impressed his political friends. But while he was proven innocent, links between the Home Rule movement and more forceful actions had been shown. He might have survived this politically if not for the next challenge.

At the Peak of His Power

From 1886 to 1890, Parnell continued to work for Home Rule. He tried to assure British voters that it would not be a threat to them. In Ireland, Unionist resistance became more organized. Parnell pursued moderate land purchase plans. He still hoped to keep some landlord support for Home Rule. During the farm crisis that grew worse in 1886, Parnell chose not to get involved with the "Plan of Campaign" organized by his assistants. He did this to protect the Home Rule cause.

It seemed that all that was left was to work out the details of a new Home Rule bill with Gladstone. They had two meetings. One was in March 1888, and a more important one was at Gladstone's home in Hawarden in December 1889. In both meetings, Parnell's requests were within what the Liberals found acceptable. Gladstone noted that Parnell was one of the best people he had ever dealt with. This was a remarkable change from being in Kilmainham Gaol to being a close contact at Hawarden in just over seven years. This was the highest point of Parnell's career. In early 1890, he still hoped to make progress on the land issue. A large part of his party was unhappy with this.

Political Downfall

Party Splits

When the yearly party leadership election was held on November 25, Gladstone's warning was not given to the members until after they had already re-elected Parnell as their leader. Gladstone published his warning in a letter the next day. Angry members demanded a new meeting, which was called for December 1. Parnell issued a statement on November 29. He said that a part of the party had lost its independence. He also misrepresented Gladstone's terms for Home Rule, saying they were not good enough. Seventy-three members were present for the important meeting in committee room 15 at Westminster. Leaders tried hard to find a compromise where Parnell would step aside temporarily. Parnell refused. He strongly insisted that the Irish party's independence could not be controlled by Gladstone or the Catholic Church. As chairman, he blocked any move to remove him. On December 6, after five days of heated debate, a majority of 44 members walked out. Led by Justin McCarthy, they formed a new group. This created two rival parties: Parnell's supporters and those against him. The 28 members who stayed loyal to Parnell continued in the Irish National League under John Redmond. But all of his former close friends, like Michael Davitt and John Dillon, left him to join the anti-Parnellites. The majority of anti-Parnellites formed the Irish National Federation. This group was later led by John Dillon and supported by the Catholic Church. The bitterness of this split tore Ireland apart and lasted for many years. Parnell died soon after, and his group became smaller. The majority group played only a small role in British or Irish politics until the next time the UK had a "hung Parliament" in 1910.

Fighting On

Parnell fought back hard, even though his health was failing. On December 10, he arrived in Dublin to a hero's welcome. He and his followers forcefully took over the offices of the party newspaper, United Irishman. A year before, his popularity had been at its highest. But this new challenge greatly hurt his support. Most rural nationalists turned against him. In a special election in North Kilkenny in December, he attracted some more radical supporters. This confused his former followers, who sometimes fought physically with his supporters. His candidate lost by almost two to one. Even though he was no longer leader, he fought a long and fierce campaign to get his position back. He traveled around Ireland to regain public support. In a special election in North Sligo, his candidate's defeat was not as big.

He married Katharine on June 25, 1891, after he had tried unsuccessfully to have a church wedding. On the same day, the Irish Catholic Church leaders, worried by the number of priests who had supported him, signed a strong statement against him. They said his "public misconduct" made him unfit to be a leader. Only Edward O'Dwyer, the bishop of Limerick, did not sign. The Parnells moved to Brighton.

He returned to fight his third and last special election in County Carlow. He had lost the support of the Freeman's Journal newspaper. At one point, a hostile crowd threw quicklime at his eyes in Castlecomer, County Kilkenny. Parnell continued his tiring campaign. He kept losing elections, but he looked forward to the next general election in 1892 to improve his situation. On September 27, he spoke to a crowd in pouring rain at Creggs. He got very wet. His health got worse during the difficult campaign. He also had kidney disease. Parnell fought fiercely, but he was a dying man, even though he was only 45.

Death and Legacy

He returned to Dublin on September 30. He died in his home in Hove on October 6, 1891, from pneumonia. He was 45 years old. Even though he was an Anglican, his funeral on October 11 was at the non-religious Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin. More than 200,000 people attended. He was so famous that his gravestone, put up in 1940, simply says "Parnell."

His brother John Howard inherited the Avondale estate. He found it had many debts and eventually sold it in 1899. Five years later, the state bought it. It is now open to the public. The "Parnell Society" holds its yearly summer school there. The "Parnell National Memorial Park" is nearby in Rathdrum, County Wicklow. Dublin has places named Parnell Street and Parnell Square. At the north end of O'Connell Street stands the Parnell Monument. This statue was planned by John Redmond and sculpted by American Augustus Saint Gaudens. It was paid for by Americans and finished in 1911.

Parnell is also remembered on the first Sunday after his death anniversary, October 6. This day is called Ivy Day. It started when mourners at his funeral in 1891 took ivy leaves from walls and put them on their clothes. This was inspired by a wreath of ivy sent by a woman from Cork. Since then, the ivy leaf has been Parnell's symbol. His followers wear it when they gather to honor him.

Since 1991, the 100th anniversary of his death, Magdalene College, Cambridge, where Parnell studied, has offered the Parnell Fellowship in Irish Studies. This is given to a scholar for study without teaching duties.

Personal Views

Parnell's personal political views were a bit of a mystery. He was good at communicating, but he was also cleverly unclear. He changed his words depending on the situation and audience. However, he always first defended working within the law to bring about change. This was sometimes difficult because of crimes linked to the Land League and opposition from landlords.

Parnell was able to support both the radical republican and atheist Charles Bradlaugh and work with the leaders of the Catholic Church. He was a close friend of Thomas Nulty, the Catholic Bishop of Meath, until his personal challenge in 1889. Parnell was linked to both the wealthy landowning class and the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Some historians even think he might have joined the latter group. He was naturally conservative. Some historians suggest he might have been closer to the Conservative Party than the Liberal Party, if not for his political goals.

Legacy

Charles Stewart Parnell had a special quality called charisma. He was a mysterious person and a talented politician. He is seen as one of the most remarkable figures in Irish and British politics. He helped change the system that his own wealthy family belonged to. Within 20 years, landlords who lived far away were almost gone from Ireland. He single-handedly created Britain's first modern, well-organized political party. He controlled all parts of Irish nationalism and also got Irish-Americans to fund the cause. He played an important role in the rise and fall of British governments in the mid-1880s. He also convinced Gladstone to support Irish Home Rule.

More than a century after his death, people are still interested in him. His death, and the personal challenge before it, gave him a public appeal that other politicians could not match. His main biographer, F. S. L. Lyons, says historians point to many major achievements. These include focusing on legal political action, the Land Act of 1881, and creating a powerful, disciplined party in Parliament. He also made sure Ireland was included in the 1884 Reform Act. He forced Home Rule to be a main issue in British politics. He also convinced most of the Liberal party to support his cause. Lyons agrees these were amazing achievements. But he stresses that Parnell did not do them alone. He worked closely with people like Gladstone and Davitt.

Gladstone described him: "Parnell was the most remarkable man I ever met. I do not say the ablest man; I say the most remarkable and the most interesting. He was an intellectual phenomenon." Liberal leader H. H. Asquith called him one of the three or four greatest men of the 19th century. Historian A. J. P. Taylor said, "More than any other man he gave Ireland the sense of being an independent nation."

Some writers wonder what Irish history would have been like if he had lived. Perhaps "All-Ireland Home Rule" could have happened with everyone's agreement. This might have prevented later events like the separate status for Ulster. It might also have prevented the Easter Rising and the Anglo-Irish War. However, some historians say this is unlikely because Unionist opposition to "All-Ireland Home Rule" was very strong after 1885.

The impact of Parnell is so great that Irish political parties today still try to claim him as their own. His personal challenge and early death changed Irish politics in ways we can only guess. He was willing to risk everything for his personal life. For many Irish people, his life as the "lost leader" was very dramatic and sad. No later leader who lived a normal life could ever match his legendary reputation.

Parnell in Stories and Films

Charles Stewart Parnell has appeared in many books and films.

- In Knut Hamsun's 1892 novel Mysteries, characters talk about Parnell and Gladstone.

- Parnell's death shocks a character in Virginia Woolf's 1937 novel The Years.

- He is praised in William Butler Yeats's 1938 poem "Come Gather Round Me, Parnellites." Yeats also mentions him in "To a Shade" and "Parnell."

- In W. Somerset Maugham's 1944 novel The Razor's Edge, the author mentions Parnell and Katharine O'Shea.

- Parnell is discussed in James Joyce's novels A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Dubliners (in "Ivy Day in the Committee Room"), and Ulysses. A character in Finnegans Wake is partly based on Parnell.

- He is a main background character in Thomas Flanagan's 1988 novel The Tenants of Time and Leon Uris's 1976 novel Trinity.

- Clark Gable played Parnell in the 1937 film Parnell.

- Robert Donat played him in the 1947 film Captain Boycott.

- Patrick McGoohan played Parnell in a 1954 TV episode called "The Fall of Parnell."

- In 1991, Trevor Eve played Parnell in the TV mini-series Parnell and the Englishwoman.

- The 1992 novel Death and Nightingales by Eugene McCabe mentions him many times.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Charles Stewart Parnell para niños

In Spanish: Charles Stewart Parnell para niños

- Irish issue in British politics

- List of people on the postage stamps of Ireland

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |