John Dillon facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

John Dillon

|

|

|---|---|

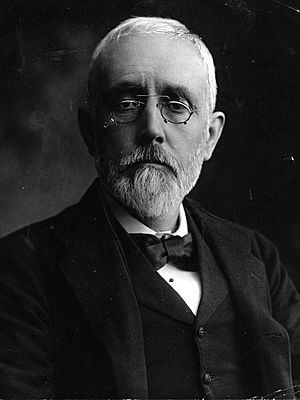

Dillon, c. 1915

|

|

| Member of Parliament for East Mayo | |

| In office 27 November 1885 – 14 December 1918 |

|

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Éamon de Valera |

| Member of Parliament for Tipperary | |

| In office 8 April 1880 – 23 March 1883 Serving with Patrick James Smyth

|

|

| Preceded by | Stephen Moore Edmund Dwyer Gray |

| Succeeded by | Patrick James Smyth Thomas Mayne |

| Leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party | |

| In office 6 March 1918 – 14 December 1918 |

|

| Preceded by | John Redmond |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Devlin |

| Leader of the Irish National Federation | |

| In office 1892–1900 |

|

| Preceded by | Justin McCarthy |

| Succeeded by | Merged into IPP |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 September 1851 Blackrock, Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 4 August 1927 (aged 75) London, England |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | |

| Relations | Anne Deane (aunt) |

| Children | 6, including Myles Dillon and James Dillon |

| Parent | John Blake Dillon (father) |

| Education |

|

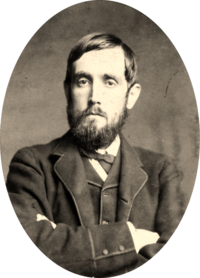

John Dillon (born September 4, 1851 – died August 4, 1927) was an important Irish politician from Dublin. He served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for over 35 years. He was also the last leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. Dillon strongly believed in Irish nationalism. He supported Charles Stewart Parnell and worked for land reform and Irish Home Rule. Home Rule meant Ireland would have its own government.

Contents

Early Life and Political Beginnings

John Dillon was born in Blackrock, Dublin. His father, John Blake Dillon, was a famous "Young Irelander". After both his parents died young, his aunt, Anne Deane, helped raise him. He went to several schools, including Trinity College Dublin and the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium. He also studied medicine.

In 1873, Dillon joined the Home Rule League. This group wanted Ireland to govern itself. He quickly became known for his strong opinions. Because his family had money, he could focus all his time on politics.

Fighting for Land Reform

Dillon became a key leader in the Irish National Land League. This group worked to help farmers. He strongly supported the idea of ""boycotting"" landlords. This meant people would refuse to deal with landlords who treated tenants unfairly. He was good friends with Michael Davitt, who also supported this idea.

In 1880, Dillon became an MP for County Tipperary. He first supported Charles Stewart Parnell, another important Irish leader. Dillon even traveled to the United States with Parnell to raise money for the Land League. When he returned, he criticized a new law meant to help farmers, saying it didn't do enough. His strong views led to his arrest in 1881.

A Radical Voice for Change

Dillon was arrested again in October 1881, along with Parnell and others. They were held in Kilmainham Gaol. While there, he signed the No Rent Manifesto, which encouraged tenants not to pay rent. Parnell later made a deal called the Kilmainham Treaty to end the "Land War." This led to their release in May 1882.

Dillon's health suffered, and he wasn't happy with some political changes. So, he left Parliament in March 1883 and moved to Colorado, America, for a short time. He returned in 1885. Parnell then chose him to run for MP in East Mayo. He won without opposition and represented this area until 1918.

The Plan of Campaign

Dillon was a main supporter of the "Plan of Campaign." This plan suggested that if landlords charged too much rent, tenants should pay their rent to the Land League instead. If a tenant was evicted, the League would support them financially. Dillon was arrested several times for his actions. For example, in 1886, he was arrested while collecting rents on a landlord's estate. He was imprisoned six times in total for his activism.

Political Splits and Reunions

In 1889, Dillon traveled to Australia and New Zealand to raise money for the Nationalist party. When he returned, he was arrested again. He was released on bail and went to America. Later, he and William O'Brien met with Parnell to discuss his leadership after a personal scandal. When talks failed, they surrendered to the police and were jailed again.

Dillon and O'Brien became unhappy with the direction of Irish politics. After Parnell's personal issues, the party split. Dillon strongly opposed Parnell and joined the larger group, the Irish National Federation (INF). Justin McCarthy became its leader.

When the Liberals came back to power in 1892, Dillon helped with talks for a second Home Rule Bill. This bill would have given Ireland more self-government, but it was rejected. Dillon then focused on leading the INF as its deputy chairman.

Party Leadership and Challenges

When Home Rule was delayed, Dillon worked to remove Timothy Healy from influence in the party. He also opposed Horace Plunkett's efforts to unite Unionists and Nationalists. Plunkett also tried to help small farmers with his co-operative movement.

In November 1895, Dillon married Elizabeth Mathew. They had six children together. In February 1896, he became chairman of the INF. He showed his strong Irish nationalist views by opposing a special address to Queen Victoria in 1897. He felt her reign had not been good for Ireland.

In 1898, William O'Brien started the "United Ireland League" (UIL). This group quickly grew and helped reunite the split Irish Parliamentary Party under John Redmond in 1900. Dillon became the party's deputy leader and supported Redmond.

Against Compromise

Dillon strongly disagreed with O'Brien's idea of "conciliation," which meant negotiating with landlords and Unionists. Dillon believed that constant pressure on landlords and the government was the best way to achieve Home Rule. He never trusted talking with the "hereditary enemy" (the British government and Unionists). His strong attacks led O'Brien to leave the party in 1903.

Dillon later gained control of the UIL through his close friend, Joseph Devlin. Dillon's approach to Home Rule became very traditional. It focused mainly on Catholic Irish people and did not include new groups or ideas.

Home Rule and World War I

Dillon sometimes had health problems, which meant he wasn't always in Parliament. However, after the Liberals won the 1906 election, he was consulted more often. Between 1910 and 1914, the question of Irish Home Rule came up again.

Dillon took a very firm stance against any compromise on Home Rule. He disagreed with Redmond, who was willing to let Ulster have some local control. Dillon believed that threats of civil war from Edward Carson's Ulster Unionist Party were just a bluff. He also strongly opposed giving women the right to vote. He believed it would "destroy the home."

When World War I began, Dillon accepted Redmond's decision to support Britain. However, he did not help recruit soldiers for the Irish divisions.

The Easter Rising and Final Years

The Easter Rising in 1916 surprised the Irish Party. After the rebellion, General Maxwell ordered many executions. Dillon stepped in to try and stop these executions. He told the British government that continuing the executions would turn public opinion against them. He argued that the rebels, though "wrong," had fought "a clean fight." The secret trials and executions did indeed make the public more sympathetic to the rebels.

After Redmond died in March 1918, Dillon became the leader of the Irish Party. When the German army attacked on the Western Front, the British government tried to force conscription (mandatory military service) on Ireland. Dillon strongly opposed this. He pulled all Irish MPs out of the House of Commons in protest. This attempt to force conscription, combined with the slow progress of Home Rule, made many Irish people support Sinn Féin. This led to Sinn Féin winning a huge victory in the next election.

Dillon tried to get the government to grant Ireland self-government in July 1918. He said that Home Rule must mean "full and complete executive, legislative and fiscal power." He also stressed that Irish unity was vital. However, he did not fully understand the need to address Ulster's concerns.

In the general election of December 1918, Dillon's party was largely defeated. He lost his own seat to Éamon de Valera. Dillon retired from politics. He lived to see the Anglo-Irish War, the creation of Northern Ireland, the Partition of Ireland, and the Irish Civil War.

Family and Legacy

John Dillon married Elizabeth Mathew in 1895. They had six children. He was tall and slim, and known for his serious nature. He also held conservative views on labor and women's rights.

Dillon died in London on August 4, 1927, at age 76. He was buried in Glasnevin cemetery, Dublin. A street in Dublin's Liberties is named after him.

One of his children was James Mathew Dillon (1902–1986). James also became a very important Irish politician and a leader of the Fine Gael party.