Irish Civil War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Irish Civil War |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Irish revolutionary period | |||||||||

National Army soldiers armed with Lewis machine guns aboard a troop transport in the Civil War |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Military support: |

(anti-Treaty forces) |

||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

c. 15,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| c. 800–900 Irish National Army killed |

|

||||||||

| Civilians: Unknown, estimates vary; c. 300–400 dead. | |||||||||

The Irish Civil War (Irish: Cogadh Cathartha na hÉireann) was a conflict in Ireland from June 1922 to May 1923. It happened right after the Irish War of Independence. This war was about setting up the Irish Free State, which was a new country separate from the United Kingdom.

The war was fought between the Provisional Government and the Irish Republican Army (IRA). The main disagreement was over the Anglo-Irish Treaty. The Provisional Government supported the treaty, which created the Irish Free State. However, the anti-treaty side believed it betrayed the idea of a fully independent Irish Republic. Many fighters on both sides had been comrades during the War of Independence.

The pro-treaty forces, who became the Free State Army, won the Civil War. They received a lot of weapons from the British government. This conflict caused many deaths and left deep divisions in Irish society for a long time. Today, two major political parties in the Republic of Ireland, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil, come from the opposing sides of this war.

Contents

Why the Irish Civil War Started

The Anglo-Irish Treaty: What Caused the Conflict?

The Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed to end the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921). This treaty created a self-governing Irish state with its own army and police. It also allowed Northern Ireland (six counties in the north-east) to stay part of the United Kingdom, which it did right away.

However, the treaty did not create the fully independent republic many Irish nationalists wanted. Instead, the Irish Free State would be a dominion within the British Empire. This meant the British monarch would still be the head of state, similar to Canada or Australia.

Another big problem was the "Oath of Allegiance" that members of the new Irish parliament (the Oireachtas) had to take. This oath swore loyalty to the King of Great Britain. Many Irish Republicans strongly objected to this. The treaty also confirmed the partition of Ireland, which had already been decided in 1920.

Michael Collins, a key Irish leader, argued that the treaty gave "the freedom to achieve freedom." He meant it was a step towards full independence. But those against the treaty believed it would never lead to complete Irish freedom.

How the Nationalist Movement Divided

The disagreement over the treaty caused a very personal split. Many on both sides had been close friends and fought together against the British. This made the conflict even more painful.

On January 7, 1922, the Dáil Éireann (the parliament of the Irish Republic) voted on the Anglo-Irish Treaty. It passed by a close vote of 64 to 57. After this, the British-recognized Provisional Government of the Irish Free State was set up.

Éamon de Valera, who was President of the Republic, resigned because the treaty was accepted. He argued that the Dáil had no right to approve it, saying they were breaking their oath to the Irish Republic. He suggested a compromise where the new Irish Free State would be linked to the British Commonwealth, but not a full member.

Many IRA officers also opposed the treaty. In March 1922, an IRA meeting rejected the Dáil's authority to accept the treaty. They formed their own "Army Executive," claiming it was the true government.

De Valera began giving speeches, especially in the province of Munster, which was very republican. He warned that if the treaty was accepted, Irish people would have to fight "Irish soldiers of an Irish government." He even said the IRA "would have to wade through the blood of the soldiers of the Irish Government."

Delay Before the June Election

Michael Collins tried to bring the IRA factions back together. He also made a deal with de Valera's anti-treaty group to campaign together in the first Free State election in June 1922. He even tried to create a republican-style constitution without mentioning the British monarchy.

However, the British government stopped this. They said it went against the treaty and threatened to intervene militarily. Collins had to agree, which broke the election pact. As a result, the pro- and anti-treaty groups ran against each other in the election.

The election on June 18, 1922, showed that most Irish voters supported the treaty. Collins's Pro-Treaty Sinn Féin party won with more votes than the Anti-Treaty Sinn Féin. Even so, de Valera and most of the IRA continued to oppose the treaty. De Valera famously said, "the majority have no right to do wrong."

After the election, the Provisional Government began setting up the National Army and a new police force. Initially, anti-treaty IRA units were allowed to take over British army barracks and their weapons. This meant that by summer 1922, the Provisional Government only controlled Dublin and a few other areas. Fighting began when the government tried to take control from these well-armed anti-treaty units.

How the War Unfolded

Fighting Begins in Dublin

On April 14, 1922, about 200 anti-treaty IRA fighters, led by Rory O'Connor, took over the Four Courts and other buildings in central Dublin. They hoped this would start a new fight with the British, which would unite the two IRA groups. But for the Provisional Government, this was an act of rebellion they had to deal with themselves.

Michael Collins wanted to avoid civil war at all costs. He left the Four Courts garrison alone until late June. However, after the election, the British government put more pressure on Collins to take control in Dublin.

Assassination and the Order to Attack

The British government's patience ran out after Field Marshal Henry Wilson was assassinated in London on June 22, 1922. Winston Churchill believed the Anti-Treaty IRA was responsible. He warned Collins that British troops would attack the Four Courts if the Provisional Government didn't act.

The final push for the Free State government came on June 26. The anti-treaty forces in the Four Courts kidnapped JJ "Ginger" O'Connell, a general in the new National Army. Collins then gave the Four Courts garrison an ultimatum to leave. When they refused, he decided to attack.

This attack was not the very first fighting of the war, but it was the "point of no return." It marked the official start of the Civil War. Collins ordered the National Army to use two 18-pounder field artillery guns supplied by the British. The anti-treaty forces in the Four Courts, who only had small arms, surrendered after three days of bombardment (June 28–30, 1922).

During the fighting, a huge explosion destroyed part of the Four Courts, including the Irish Public Record Office. Many historical documents were lost. Some believe the anti-treaty forces deliberately set off mines, while others think their ammunition accidentally exploded.

Street fighting continued in Dublin until July 5. Republican leader Cathal Brugha was killed. The Free State took over 500 Republican prisoners. After this, the Free State government controlled Dublin, and the anti-treaty forces spread out, mostly to the south and west of the country.

The Two Sides: Pro-Treaty vs. Anti-Treaty

The Civil War forced people to choose sides. Those who supported the treaty were called "pro-treaty" or the Free State Army (officially the National Army). Their opponents called themselves Republicans or "anti-treaty" forces, also known as "Irregulars."

The Anti-Treaty IRA believed they were defending the Irish Republic that had been declared in 1916. Éamon de Valera served as a volunteer, but Liam Lynch led the military operations until he was killed in April 1923. Frank Aiken then took over.

At the start of the war, the Anti-Treaty IRA had more fighters (about 12,000) than the pro-Free State forces (about 8,000). Many of them were experienced guerrilla fighters. However, the IRA lacked a strong command, a clear plan, and enough weapons. They mostly had rifles, some machine guns, and shotguns. They had no artillery.

In contrast, the Free State government quickly grew its army. Michael Collins and his commanders built a force that could defeat their opponents in open battles. They received a lot of help from the British, including artillery, aircraft, armored cars, and many rifles and machine guns. By the end of the war, the National Army had grown to 55,000 soldiers.

Many of the new National Army recruits were veterans of the British Army from World War I. This led to Republicans calling the Free State forces a British proxy. However, most Free State soldiers were new recruits with no military experience.

Free State Takes Control of Major Towns

After Dublin was secured, the conflict spread. Anti-treaty forces held cities like Cork, Limerick, and Waterford, calling it the "Munster Republic." But they were not ready for a traditional war.

In August 1922, the Free State easily captured these major towns. Collins and his commanders planned a nationwide attack. They sent troops by land to Limerick and Waterford, and by sea to Cork, Kerry, and Mayo. Limerick and Waterford fell on the same day (July 20). Cork city fell on August 10 after a sea landing.

While Republicans fought hard in some places, they could not defeat regular forces with artillery and armored vehicles. The Free State quickly gained control over most of the country's main areas.

Guerrilla Warfare and Key Deaths

After the major towns fell, the war turned into a guerrilla warfare campaign. Anti-treaty units spread out into small groups, like they had done against the British. They held out in parts of Cork, Kerry, Wexford, Sligo, and Mayo.

August and September 1922 saw many attacks on Free State forces. Michael Collins was killed in an ambush by anti-treaty Republicans in County Cork in August 1922. This made the Free State leaders even more determined and led to more harsh actions. Arthur Griffith, the Free State president, had also died ten days before Collins.

For a short time, it seemed the Free State might collapse due to rising casualties and the loss of its two main leaders. However, as winter came, the Republicans found it harder to continue their campaign. Free State forces broke up many large Republican groups. Anti-treaty units were forced to split into smaller groups due to lack of supplies.

By late 1922 and early 1923, the anti-treaty campaign mostly involved sabotage and destroying public buildings like roads and railways. They also started burning the homes of Free State Senators and wealthy Anglo-Irish families. In October 1922, Éamon de Valera set up his own "Republican government," but it had no real control over the country.

Harsh Actions and Executions

The final part of the Civil War became very harsh, leaving a bitter feeling in Irish politics. On September 27, 1922, the Free State government passed a law allowing military courts to give out life imprisonment or the death penalty for anti-government actions.

The Free State began executing Republican prisoners on November 17, 1922. Five IRA men were shot. On November 24, Erskine Childers, a famous author and treaty negotiator, was also executed. In total, 81 Republican prisoners were officially executed by the Free State.

In response, the Anti-Treaty IRA assassinated Seán Hales, a member of parliament, on December 7, 1922. The next day, four important Republicans—Rory O'Connor, Liam Mellows, Richard Barrett, and Joe McKelvey—were executed in revenge.

Free State troops, especially in County Kerry, also carried out unofficial executions of captured anti-treaty fighters. One well-known event happened at Ballyseedy, where nine Republican prisoners were tied to a landmine. Eight were killed when it exploded.

The Catholic Church supported the Free State as the lawful government. On October 10, 1922, the Catholic Bishops of Ireland said that the anti-treaty campaign was "without moral sanction" and that killing National soldiers was "murder before God." This support from the Church made some Republicans very angry.

The War Ends

By early 1923, the IRA's ability to fight was greatly weakened. When Republican leader Liam Deasy was captured in February 1923, he urged Republicans to end their campaign. The Free State's executions of prisoners also lowered morale among Republicans.

The National Army continued to break up the remaining Republican groups. By April 1923, it was clear the end of the war was near.

On April 10, Liam Lynch, the Republican leader, was killed in a fight in the Knockmealdown Mountains. His death allowed Frank Aiken, who took over as IRA Chief of Staff, to call for an end to the fighting. On May 24, 1923, Aiken issued a ceasefire order to IRA volunteers. He told them to hide their weapons instead of surrendering or continuing a fight they couldn't win.

Éamon de Valera supported this order. He told anti-treaty fighters that the Republic could no longer be defended by their weapons and that further fighting would be pointless.

Aftermath of the War

After the ceasefire, thousands of anti-treaty IRA members were arrested by Free State forces. Many had hidden their weapons and returned home.

An election was held on August 27, 1923. Cumann na nGaedheal, the pro-Free State party, won. The Republicans, represented by Sinn Féin, won fewer votes, and many of their candidates were still in prison.

In October 1923, about 8,000 Republican prisoners went on a hunger strike. It lasted 41 days but had little success. However, it helped focus the Republican movement on the prisoners.

Attacks on Former Unionists

During the war, anti-treaty forces attacked the homes of wealthy Anglo-Irish landowners and some Southern Unionists. A total of 192 "stately homes" were destroyed.

The main reason for these attacks was that some landowners had become Free State senators. For example, the homes of Senator Horace Plunkett and Senator Henry Guinness were attacked.

These attacks also reflected anger towards those who had supported the British during the War of Independence. In July 1922, the IRA ordered that unionist property should be taken over to house their men. The worst period of attacks was in early 1923, with 37 "big houses" burned in January and February alone.

Some small farmers also took over land belonging to political opponents. There were also some attacks with religious reasons, such as the burning of a Protestant boys' orphanage in County Galway in June 1922. Many Protestants left Ireland during and after the Civil War.

War's Impact and Costs

The Civil War was short but very costly. Many important public figures were killed, including Michael Collins, Cathal Brugha, Arthur Griffith, and Liam Lynch. Both sides carried out harsh actions.

The exact number of dead and wounded is not fully known. Pro-treaty forces lost between 800 and 1,000 people. The Republican side's death toll was likely higher, with at least 426 listed. Overall, estimates for total deaths range from 1,500 to 4,000.

The new police force, the Garda Síochána, was not involved in the war. This helped it become an unarmed and neutral police service later.

The war also caused huge economic damage. Republicans burned many buildings and businesses. The destruction of railway lines and roads was especially damaging. The cost of property damage was estimated at £50 million in 1922, which is a lot of money today. The cost of fighting the war was another £17 million. This weakened the new Free State's finances.

Political Outcomes and Legacy

The fact that the Irish Civil War was fought between Irish nationalist groups meant that the conflict in Northern Ireland ended. Michael Collins had secretly supplied arms to the Northern IRA, but this stopped just before his death. The Civil War allowed Northern Ireland to become more stable and confirmed the partition of Ireland.

In 1926, Éamon de Valera and Frank Aiken left the anti-treaty Sinn Féin party. They formed the Fianna Fáil party, which decided to participate in constitutional politics. Fianna Fáil became the most powerful party in Irish politics for many years. Sinn Féin became a much smaller party.

In 1927, Fianna Fáil members took the Oath of Allegiance and entered the Dáil, which meant they accepted the Free State's legitimacy. The Free State was already moving towards greater independence. In 1931, the British Parliament gave up its right to make laws for British Commonwealth members.

When Fianna Fáil came to power in 1932, de Valera began removing parts of the treaty he disliked. He abolished the Oath of Allegiance and removed the power of the Governor General. In 1937, they passed a new constitution that made a President the head of state and claimed Northern Ireland. The next year, Britain returned the seaports it had kept under the treaty.

During World War II, Ireland remained neutral, showing its independence. Finally, in 1948, a government made up of both pro- and anti-treaty elements declared the state the Republic of Ireland and left the British Commonwealth. By the 1950s, the main issues of the Civil War were mostly settled.

The Civil War left a lasting impact on Irish politics. The two largest political parties for most of Ireland's history, Fianna Fáil (descendants of the anti-treaty side) and Fine Gael (descendants of the pro-treaty side), were shaped by this conflict. Until the 1970s, many important Irish politicians were Civil War veterans. This often made relations between the two parties difficult.

The IRA, however, continued to exist in various forms. It wasn't until 1948 that the IRA stopped military attacks on the southern Irish state. After that, the organization focused mainly on ending British rule in Northern Ireland.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Guerra civil irlandesa para niños

In Spanish: Guerra civil irlandesa para niños

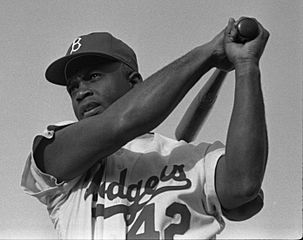

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |