The Troubles facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Troubles |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Political map of Ireland |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

State security forces:

|

Irish republican paramilitaries:

|

Ulster loyalist paramilitaries:

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

||||||||

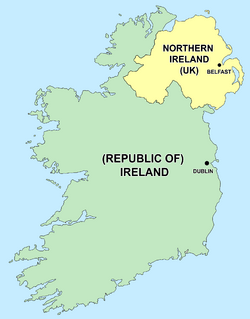

The Troubles was a period of conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted for about 30 years, from the late 1960s to 1998. It is also known as the Northern Ireland conflict. The conflict was about whether Northern Ireland should stay in the United Kingdom or join the Republic of Ireland to form a united Ireland.

The two main sides in the conflict were:

- Unionists (also called loyalists), who were mostly Ulster Protestants. They wanted Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom.

- Nationalists (also called republicans), who were mostly Irish Catholics. They wanted Northern Ireland to leave the United Kingdom and form a united Ireland.

Although the two sides were mostly divided by religion, the conflict was mainly about national identity and politics, not religion itself. The Troubles mostly took place in Northern Ireland, but sometimes the violence spread to the Republic of Ireland, England, and other parts of Europe. The conflict officially ended with the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, which was a peace deal signed by most of the political parties in Northern Ireland.

Contents

What Caused the Troubles?

The roots of the conflict go back hundreds of years. In the 1600s, many Protestant settlers from England and Scotland moved to the Ulster province of Ireland. This created a division between them and the native Irish Catholics.

In 1921, Ireland was divided into two parts. The larger part became the Irish Free State (now the Republic of Ireland), an independent country. Six counties in the north, which had a Protestant majority, became Northern Ireland and remained part of the United Kingdom.

From the 1920s onwards, the government of Northern Ireland was controlled by unionists. The Catholic minority faced discrimination. This meant they were treated unfairly in jobs, housing, and voting. For example, electoral boundaries were drawn to give unionists more political power, even in areas where more nationalists lived. These long-standing tensions eventually boiled over in the late 1960s.

How the Conflict Began

The Civil Rights Movement

In the mid-1960s, a civil rights movement began in Northern Ireland. Inspired by the civil rights movement in the United States, they organised peaceful marches to demand an end to discrimination against Catholics.

They wanted:

- An end to unfairness in jobs and housing.

- Fair voting rights for everyone ("one man, one vote").

- An end to the unfair drawing of electoral boundaries.

- Changes to the police force, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), which was over 90% Protestant.

Many unionists saw the civil rights movement as a threat and a front for Irish republicanism. Loyalist groups often attacked the marches, and the police did little to protect the marchers.

Riots and the Army's Arrival

In October 1968, a civil rights march in Derry was banned. When people marched anyway, the RUC used force to break it up. TV cameras filmed the event, and the images were shown around the world. This caused outrage and led to more protests and riots.

Tensions grew, and in August 1969, heavy rioting broke out in Derry and Belfast. In Derry, a three-day riot known as the Battle of the Bogside took place between residents and the police. To restore order, the British government sent the British Army to Northern Ireland. At first, many Catholics welcomed the army, hoping they would be more neutral than the RUC. However, this feeling did not last long.

A Time of Great Violence

The 1970s was the most violent period of the Troubles. Paramilitary groups on both sides became more active. These were illegal armed groups that used violence to achieve their political goals. The main republican group was the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), and the main loyalist groups were the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and Ulster Defence Association (UDA).

Bloody Sunday

A key event happened on 30 January 1972, known as Bloody Sunday. British soldiers shot 26 unarmed civilians during a protest march in Derry. Thirteen people died on the day, and another died later from his injuries.

Bloody Sunday caused huge anger among the nationalist community. Many more people joined the IRA, and the violence in Northern Ireland got much worse.

Direct Rule

The situation became so unstable that in March 1972, the British government suspended the Northern Ireland parliament. It began to rule the region directly from London. This was called "direct rule" and was meant to be temporary, but it lasted for most of the next 30 years.

Throughout the 1970s, the IRA carried out bombing campaigns and attacks on British security forces. Loyalist paramilitaries attacked Catholics and republicans. Thousands of people were killed or injured during this decade.

The "Long War" and a Search for Solutions

By the late 1970s, the IRA had changed its strategy to what it called the "Long War". This meant a long-term campaign of violence that they believed could continue for many years.

The Hunger Strikes

In 1981, a major event took place inside the Maze prison. Republican prisoners went on a hunger strike to demand the right to be treated as political prisoners, not as ordinary criminals. Ten prisoners, led by Bobby Sands, starved themselves to death.

While on hunger strike, Bobby Sands was elected as a Member of Parliament. The hunger strikes gained a lot of support for the republican cause. It led Sinn Féin, the IRA's political wing, to become more involved in politics and elections.

Continued Violence

Violence continued throughout the 1980s. The IRA carried out major attacks, including the Brighton hotel bombing in 1984, which was an attempt to kill British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and her cabinet. In 1987, an IRA bomb killed 11 people at a Remembrance Sunday ceremony in Enniskillen. Loyalist groups also continued their attacks.

The Path to Peace

By the early 1990s, many people on both sides were tired of the violence. Secret talks began between political leaders and the British and Irish governments to find a peaceful solution.

In 1994, the main paramilitary groups announced ceasefires, meaning they would stop their campaigns of violence. Although the IRA's ceasefire broke down for a time, it was later restored in 1997. This opened the door for all-party peace talks.

The Good Friday Agreement

On 10 April 1998, after years of negotiations, the Good Friday Agreement (or Belfast Agreement) was signed. This was a historic peace deal supported by most of Northern Ireland's political parties, as well as the British and Irish governments.

The agreement set up a new government for Northern Ireland based on power-sharing. This meant that unionist and nationalist parties had to share power and make decisions together. It also included promises on human rights, police reform, and the release of paramilitary prisoners. In a vote, the people of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland overwhelmingly approved the agreement.

Northern Ireland After the Peace Deal

The Good Friday Agreement was a major success and largely ended the Troubles. The main paramilitary groups gave up their weapons. However, the path to lasting peace has had its challenges.

Small "dissident republican" groups who rejected the peace deal have continued to carry out some attacks, like the Omagh bombing in 1998 which killed 29 people.

The power-sharing government has been suspended several times due to disagreements between the parties, but it has always been restored. Today, Northern Ireland is much more peaceful, but some division between the two communities remains. In some towns and cities, "peace walls" still separate unionist and nationalist neighbourhoods.

Dealing with the Past

For many years, there have been discussions about how to deal with the legacy of the Troubles, including unsolved crimes. In 2023, the UK government passed the Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Act. This law aimed to end most prosecutions for crimes related to the conflict and set up a new body to investigate cases.

The act was very controversial. It was opposed by all major political parties in Northern Ireland, victims' groups, and the Irish government. In response, the Irish government challenged the law in the European Court of Human Rights. In September 2025, the British and Irish governments announced new joint proposals to help address legacy issues and support victims' families.

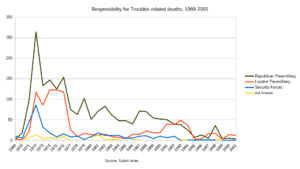

The Human Cost of the Conflict

The Troubles had a devastating impact on the people of Northern Ireland.

- Over 3,500 people were killed.

- Over 47,000 people were injured.

- About half of those killed were civilians (ordinary people not involved in the conflict).

Republican paramilitaries were responsible for about 60% of the deaths. Loyalist paramilitaries were responsible for about 30%, and British security forces were responsible for about 10%.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Conflicto norirlandés para niños

In Spanish: Conflicto norirlandés para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |