Bloody Sunday (1972) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bloody Sunday |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Troubles | |

The Catholic priest Edward Daly waving a blood-stained white handkerchief while trying to escort the mortally wounded Jackie Duddy to safety

|

|

| Location | Derry, Northern Ireland |

| Coordinates | 54°59′49″N 07°19′32″W / 54.99694°N 7.32556°W |

| Date | 30 January 1972 16:10 (UTC+00:00) |

|

Attack type

|

Mass shooting |

| Weapons | L1A1 SLR rifles |

| Deaths | 14 (13 immediate, 1 died four months later) |

|

Non-fatal injuries

|

15+ (12 from gunshots, two from vehicle impact, others from rubber bullets and flying debris) |

| Perpetrators | British Army (Parachute Regiment) |

Bloody Sunday, also known as the Bogside Massacre, was a terrible event that happened on January 30, 1972. British soldiers shot 26 unarmed people during a protest march in Derry, Northern Ireland. Thirteen people died right away, and another person died four months later from their injuries. Many victims were shot while running away. Some were shot while trying to help others who were hurt.

Other protesters were injured by small pieces of metal, rubber bullets, or police sticks. Two people were hit by British Army vehicles. All those shot were Catholics. The march was organized by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA). They were protesting against people being put in prison without a trial. The soldiers involved were from the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment. This was the same group involved in the Ballymurphy massacre a few months earlier.

The British government held two investigations. The first, called the Widgery Tribunal, mostly said the soldiers were not to blame. It said some shooting was "reckless" but accepted claims that soldiers shot at armed people. Many people criticized this report, calling it a "whitewash". The second investigation, the Saville Inquiry, started in 1998. After 12 years, its report came out in 2010. It said the killings were "unjustified" and "unjustifiable". It found that all those shot were unarmed and not a serious threat. It also said no bombs were thrown. The report concluded that soldiers "knowingly put forward false accounts" to excuse their actions. When the report was published, British Prime Minister David Cameron formally apologized.

Bloody Sunday is seen as one of the most important events of the Troubles. This is because so many civilians were killed by government forces in public. It was the highest number of people killed in one shooting during the conflict. It made many Catholics and Irish nationalists angry at the British Army. Support for the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) grew, especially in Derry. The Republic of Ireland had a national day of mourning. Huge crowds protested and burned down the British Embassy in Dublin.

Contents

Why the March Happened

Life in Derry Before 1972

The city of Derry felt unfair to many Catholics and Irish nationalists in Northern Ireland. Even though most people in Derry were nationalist, elections were set up so that Unionists always won. This was called gerrymandering. The city also seemed to get less money for public projects. For example, a university was built in a smaller, Protestant-majority town instead of Derry. Also, many homes in the city were in bad condition.

Because of these problems, Derry became a main place for the civil rights movement in the late 1960s. Groups like the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) led this movement. In August 1969, a big riot called the Battle of the Bogside happened there. This led the Northern Ireland government to ask for military help.

Many Catholics first welcomed the British Army. They saw them as a fair group, unlike the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) police force, which they thought was unfair. But soon, relations between them got worse.

Rules and Violence Increase

To stop growing violence across Northern Ireland, a new rule was made on August 9, 1971. This rule allowed people to be put in prison without a trial. This was called internment without trial. After this rule, violence increased. In three days, 21 people were killed. In Belfast, soldiers from the Parachute Regiment shot and killed eleven civilians. This event became known as the Ballymurphy Massacre.

On August 10, a British soldier was killed by a sniper in Derry. A month after internment, a 14-year-old Catholic schoolgirl was shot dead by a British soldier in Derry. Two months later, a 47-year-old mother of six was shot dead in her garden by the British Army.

The IRA also became more active. Thirty British soldiers were killed in the last months of 1971. Before internment, only ten soldiers had been killed that year. By the end of 1971, six more soldiers had died in Derry. The British Army was shot at over 1,300 times and faced many explosions. Both the Provisional IRA and the Official IRA built walls and created "no-go areas" in Derry. These were places the British Army and police could not easily enter. By the end of 1971, 29 walls blocked access to an area known as Free Derry. Some of these walls were too strong even for the Army's armored vehicles.

Planning the March

On January 18, 1972, the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Brian Faulkner, banned all parades and marches. But four days later, a march against internment was held near Derry. Protesters marched to a prison camp but were stopped by soldiers. When some protesters threw stones, soldiers pushed them back with rubber bullets and sticks. Reports said the soldiers beat many protesters badly.

The NICRA planned another anti-internment march in Derry for January 30. The authorities decided to let the march happen in the Bogside area. But they planned to stop it from reaching Guildhall Square, where the rally was supposed to be. This was to prevent riots. Major General Robert Ford, a British Army commander, ordered the 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment (1 Para) to go to Derry. Their job was to arrest rioters. This plan was called 'Operation Forecast'. The Saville Report later criticized Ford for choosing the Parachute Regiment. This group had a "reputation for using excessive physical violence."

What Happened on Bloody Sunday

The paratroopers arrived in Derry on the morning of the march. They took their positions. Brigadier Pat MacLellan was in charge of the operation. He gave orders to Lieutenant Colonel Derek Wilford, who commanded 1 Para. Wilford then gave orders to Major Ted Loden, who led the soldiers who would make arrests.

The protesters planned to march from Bishop's Field to the Guildhall in the city center. The march started around 2:45 p.m. There were between 10,000 and 15,000 people. Many joined along the way.

The march went along William Street. But as it got near the city center, British Army barriers blocked the way. The organizers changed the route to Rossville Street. They planned to hold the rally at Free Derry Corner instead. However, some people left the march and started throwing stones at soldiers. The soldiers fired rubber bullets, tear gas, and water cannons. These clashes were common, and observers said this riot was not worse than usual.

Some people saw paratroopers in an empty building overlooking William Street. They started throwing stones at the windows. Around 3:55 p.m., these paratroopers opened fire. Civilians Damien Donaghy and John Johnston were shot and wounded. These were the first shots. The soldiers claimed Donaghy had an object, but the Saville Inquiry later said all those shot were unarmed.

At 4:07 p.m., the paratroopers were ordered to go through the barriers and arrest rioters. The soldiers, on foot and in armored vehicles, chased people down Rossville Street and into the Bogside. Two people were hit by the vehicles. Brigadier MacLellan had ordered only one group of soldiers to go through the barriers, on foot. He also said they should not chase people down Rossville Street. Wilford did not follow this order. This meant there was no separation between rioters and peaceful marchers. Many people said paratroopers beat them, hit them with rifle butts, and fired rubber bullets at close range. The Saville Report agreed that soldiers "used excessive force when arresting people."

One group of paratroopers took a position near a low wall. This was about 80 yards in front of a pile of rubble that blocked Rossville Street. People were at the rubble barrier, and some were throwing stones. But they were not close enough to hit the soldiers. The soldiers fired at the people at the barrier. Six people were killed, and a seventh was wounded.

A large group of people ran into the car park of Rossville Flats. This area was like a courtyard, surrounded by tall buildings. The soldiers opened fire, killing one civilian and wounding six others. This person, Jackie Duddy, was running next to a priest, Edward Daly, when he was shot in the back.

Another group of people ran into the car park of Glenfada Park, also surrounded by buildings. Here, soldiers shot at people across the car park, about 40-50 yards away. Two civilians were killed, and at least four others were wounded. The Saville Report said it was likely that at least one soldier fired randomly into the crowd. The paratroopers went through the car park. Some soldiers went out one corner and shot two civilians dead. Other soldiers went out another corner and shot four more civilians, killing two.

About ten minutes passed from when the soldiers entered the Bogside until the last civilian was shot. More than 100 shots were fired by the soldiers. No warnings were given before the soldiers started shooting.

Some of those shot were given first aid by volunteers. They were then driven to the hospital in cars or ambulances. The first ambulances arrived at 4:28 p.m. The three boys killed at the rubble barrier were driven to the hospital by paratroopers. Witnesses said soldiers lifted the bodies and put them in their armored vehicle "as if they were pieces of meat." The Saville Report agreed this was an "accurate description."

Who Was Injured or Killed?

In total, 26 people were shot by the paratroopers. Thirteen died on the day. Another person died from their injuries four months later. The people who died were killed in four main areas: the rubble barrier on Rossville Street, the car park of Rossville Flats, the area in front of Rossville Flats, and the car park of Glenfada Park.

All the soldiers involved said they had shot at armed people or bomb-throwers. No soldier said they missed their target and hit someone by mistake. However, the Saville Report found that all those shot were unarmed. It said none of them were a serious threat. It also concluded that soldiers did not fire because they were attacked by armed people.

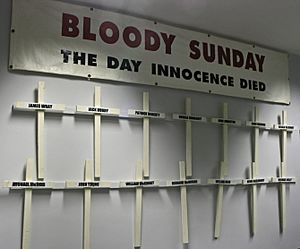

Here are the people who died:

- John "Jackie" Duddy, age 17. Shot while running away from soldiers. He was the first person to die. Both investigations said he was unarmed.

- Michael Kelly, age 17. Shot in the stomach while standing at the rubble barrier. Both investigations said he was unarmed.

- Hugh Gilmour, age 17. Shot while running away from soldiers near the rubble barrier.

- William Nash, age 19. Shot in the chest at the rubble barrier. Three people were shot while trying to help him.

- John Young, age 17. Shot in the face at the rubble barrier, while trying to help William Nash.

- Michael McDaid, age 20. Shot in the face at the rubble barrier, also while trying to help William Nash.

- Kevin McElhinney, age 17. Shot from behind near the rubble barrier, while trying to crawl to safety.

- James "Jim" Wray, age 22. Shot in the back while running away. He was then shot again in the back while lying on the ground.

- William McKinney, age 26. Shot in the back while trying to run away through Glenfada Park.

- Gerard "Gerry" McKinney, age 35. Shot in the chest. Witnesses said he held up his arms and shouted, "Don't shoot!" before being shot.

- Gerard "Gerry" Donaghy, age 17. Shot in the stomach while standing behind Gerard McKinney. They might have been hit by the same bullet. Soldiers later found bombs in his pockets. But people who helped him, including a doctor, said they did not see any bombs. This led to claims that soldiers put the bombs on him to make the killings seem right.

- Patrick Doherty, age 31. Shot from behind while trying to crawl to safety. Photographs show he was unarmed.

- Bernard "Barney" McGuigan, age 41. Shot in the back of the head when he went to help Patrick Doherty. He was waving a white handkerchief to show he was peaceful.

- John Johnston, age 59. Shot in the leg and shoulder earlier, before most of the shooting started. He was not on the march. He died four months later, and his death was linked to his injuries.

What Happened After Bloody Sunday

Thirteen people were killed right away, and one more died later from injuries. Everyone who saw the event, except the soldiers, said that soldiers shot into an unarmed crowd. They said soldiers aimed at people running away or helping the wounded. No British soldier was hurt by gunfire or bombs. No bullets or bombs were found to support the soldiers' claims.

The British Army said that paratroopers fired back at armed people. Bernadette Devlin, a Member of Parliament who saw the shootings, was very angry. She hit the Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling, for his comments.

On February 2, 1972, tens of thousands of people went to the funerals of eleven victims. In the Republic of Ireland, it was a national day of mourning. There was a huge general strike. Memorial services were held in churches and synagogues. Schools closed, and public transport stopped. Large crowds protested at the British embassy in Dublin. The building was attacked with stones and petrol bombs and burned down. Relations between Ireland and the UK became very bad.

The Official IRA tried to get revenge for Bloody Sunday. On February 22, 1972, they set off a car bomb at Aldershot military barracks. This was the headquarters of the Parachute Brigade. Seven support staff were killed.

The First Investigation: Widgery Inquiry

Two days after Bloody Sunday, the British Parliament decided to hold an investigation. Prime Minister Edward Heath asked Lord Widgery to lead it. Many witnesses did not want to take part because they did not trust Widgery to be fair. But many were convinced to join.

Widgery's report was finished quickly, in just ten weeks. It supported the British Army's story. It said soldiers fired back at armed people. It said, "None of the deceased or wounded is proved to have been shot whilst handling a firearm or bomb." But it added that there was "a strong suspicion that some others had been firing weapons or handling bombs." Evidence included tests for gun residue and claims that bombs were found on one body. However, tests for explosives on the clothes of eleven victims were negative. It was also argued that gun residue on some victims could have come from contact with soldiers.

Widgery said the march organizers were responsible. He concluded, "There would have been no deaths [...] if those who organised the illegal march had not thereby created a highly dangerous situation."

Most people who saw the event disagreed with the report. They called it a "whitewash". A popular slogan in Derry was "Widgery washes whiter," making fun of a soap advertisement.

In 1992, British Prime Minister John Major said that those killed on Bloody Sunday should be seen as innocent. He said they were not shot while handling weapons or explosives.

The Second Investigation: Saville Inquiry

In 1998, Prime Minister Tony Blair agreed to hold a new public investigation into Bloody Sunday. This inquiry was led by Lord Saville. It started in April 1998. The inquiry heard from witnesses in Derry from March 2000 to November 2004. The Saville Inquiry was much more detailed than the Widgery Tribunal. It interviewed many witnesses, including local people, soldiers, journalists, and politicians. It also looked at many photos and videos.

Colonel Wilford, who was in charge of the soldiers, was angry about the new inquiry. He said he was proud of what he did on Bloody Sunday. Later, in 2000, Wilford said, "There might have been things wrong in the sense that some innocent people [...] were wounded or even killed. But that was not done as a deliberate malicious act." In 2007, General Mike Jackson, who was a captain on Bloody Sunday, said: "I have no doubt that innocent people were shot." This was different from what he had said for over thirty years.

One former soldier said that a lieutenant told them the night before Bloody Sunday: "Let's teach these buggers a lesson - we want some kills tomorrow." This soldier did not see anyone with a weapon or hear any explosions. He said some soldiers were excited and shot out of bravery or anger. He also said his first statement to the Widgery Inquiry was changed.

Many people claimed that the British Ministry of Defence (MoD) tried to stop the inquiry. Over 1,000 Army photos and original helicopter videos were never given to the inquiry. Also, the guns used by the soldiers on Bloody Sunday were lost by the MoD. The MoD said all the guns were destroyed. But some were later found in other places.

By the time the inquiry finished hearing evidence, it had interviewed over 900 witnesses. It was the biggest investigation in British legal history. It was also the longest and most expensive, taking twelve years and costing £195 million.

The Saville Report's Findings

The report was published on June 15, 2010. It concluded: "The firing by soldiers of 1 PARA on Bloody Sunday caused the deaths of 13 people and injury to a similar number, none of whom was posing a threat of causing death or serious injury." It said British soldiers "lost control." They shot people who were running away and those who tried to help the wounded. The civilians were not warned before soldiers shot them.

The report also found that the victims were unarmed. No bombs were thrown, which was different from what the soldiers claimed. It said that while some soldiers might have fired out of fear, others fired at civilians they knew were unarmed. The report stated that soldiers had made up lies to hide what they did.

The inquiry found that an Official IRA sniper fired one shot at British soldiers. This happened after the British soldiers had shot Damien Donaghey and John Johnston. The report also said an Official IRA member fired a handgun at a British armored vehicle. But there was no proof that soldiers noticed this.

Martin McGuinness, a senior member of Sinn Féin, said he was a leader of the Provisional IRA in Derry and was at the march. One person told the inquiry that McGuinness gave him bomb parts on Bloody Sunday. McGuinness said these claims were "fantasy." The inquiry was not sure about McGuinness's actions that day. It said he was probably armed, but there was not enough evidence to say if he fired his weapon. It concluded that he "did not engage in any activity that provided any of the soldiers with any justification for opening fire."

Regarding the soldiers in charge, the inquiry found:

- Lieutenant Colonel Derek Wilford: He was in charge of the soldiers. He "deliberately disobeyed" his superior by sending soldiers into the Bogside without telling him.

- Major Ted Loden: He was in charge of the soldiers who fired. He was cleared of wrongdoing. The report said he "neither realised nor should have realised that his soldiers were or might be firing at people who were not posing [...] a threat."

- Captain Mike Jackson: He was an officer on Bloody Sunday. He was cleared of bad actions for making a list of what soldiers said about their firing.

- Major General Robert Ford: He was in charge of British forces in Northern Ireland. He was cleared of fault. But his choice of 1 Para, and Wilford to lead, was seen as concerning. This was because "1 PARA was a force with a reputation for using excessive physical violence."

- Brigadier Pat MacLellan: He was the overall commander. He was cleared of wrongdoing because he believed Wilford would follow orders.

The inquiry found that Lance Corporal F was responsible for five of the killings.

Prime Minister Cameron said, "you do not defend the British Army by defending the indefensible." He admitted that all those who died were unarmed. He also said a British soldier fired the first shots at civilians. Cameron then apologized on behalf of the British Government, saying he was "deeply sorry."

Impact of Bloody Sunday

When the British Army first came to Northern Ireland, many Catholics welcomed them. They thought the Army would protect them from Protestant groups and the police. But after Bloody Sunday, many Catholics turned against the British Army. They saw them as an enemy. Young nationalists became more interested in armed republican groups. The Provisional IRA gained support from angry young people.

In the next twenty years, the Provisional IRA and other smaller republican groups increased their attacks. Other armed groups also appeared on the Protestant side. These groups included the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). The conflict, known as the Troubles, caused thousands of deaths.

In 1979, the Provisional IRA killed 18 British soldiers in the Warrenpoint ambush. Most of them were paratroopers. This happened the same day the IRA killed Lord Mountbatten. Republicans said this attack was revenge for Bloody Sunday. Graffiti appeared saying, "13 gone and not forgotten, we got 18 and Mountbatten."

In recent years, some loyalists have put up Parachute Regiment flags around the time of Bloody Sunday anniversaries. In January 2013, before the yearly Bloody Sunday march, several Parachute Regiment flags were flown in loyalist areas of Derry. Nationalist politicians and victims' families condemned this. The Ministry of Defence also spoke against the flags.

Artistic Responses to Bloody Sunday

Many artists created works about Bloody Sunday.

- Paul McCartney released the song "Give Ireland Back to the Irish" just two days after the event. The BBC banned this song.

- John Lennon's 1972 album Some Time in New York City has a song called "Sunday Bloody Sunday".

- Irish poet Thomas Kinsella's 1972 poem Butcher's Dozen is an angry response to the Widgery Tribunal.

- Black Sabbath's Geezer Butler wrote the lyrics to "Sabbath Bloody Sabbath" in 1973. He said it was inspired by Bloody Sunday.

- The Roy Harper song "All Ireland" from 1973 is critical of the military.

- Brian Friel's 1973 play The Freedom of the City tells the story from the viewpoint of three civilians.

- Irish poet Seamus Heaney's Casualty (1981) criticizes Britain for the death of his friend.

- The Irish rock band U2 remembered the event in their 1983 song "Sunday Bloody Sunday".

- Christy Moore's song "Minds Locked Shut" is about the events of the day and names the dead.

- Two 2002 television films, Bloody Sunday and Sunday, dramatized the events.

- The Celtic metal band Cruachan also had a song called "Bloody Sunday" on their 2002 album.

- The play Bloody Sunday: Scenes from the Saville Inquiry opened in London in 2005. It was based on the Saville Inquiry.

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |