Ulster Defence Regiment facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ulster Defence Regiment CGC |

|

|---|---|

| Active | 1970–1992 |

| Country | |

| Type | Infantry regiment |

| Role | To assist the RUC |

| Size | 11 battalions (at peak) |

| Regimental Headquarters | Lisburn |

| Motto(s) | "Quis Separabit" (Latin) "Who Shall Separate Us?" |

| March | (Quick) Garryowen & Sprig of Shillelagh (Slow) “Eileen Allanagh” |

| Commanders | |

| Colonel Commandant | First: General Sir John Anderson GBE, KCB, DSO. Last: General Sir Charles Huxtable, KCB, CBE, DL |

| Colonel of the Regiment | Colonel Sir Anderson Faulkner CBE |

| Insignia | |

| Regimental Flag |  |

The Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) was a special army group in the British Army. It was created in 1970 and ended in 1992. The UDR was formed to help protect people and property in Northern Ireland from attacks. Unlike other British soldiers, they did not handle large crowds or riots.

At its busiest, the UDR was the largest infantry regiment in the British Army. It started with seven groups, called battalions, and added four more within two years. Most of its members were part-time volunteers until 1976, when full-time soldiers joined.

The UDR was meant to include people from all backgrounds in Northern Ireland. When it started, about 18% of its soldiers were Catholic. However, this number dropped to about 3% by the end of 1972. The UDR was unique because it was always on active duty for its entire 22 years. It was also the first British Army infantry group to fully include women soldiers.

In 1992, the UDR joined with another group, the Royal Irish Rangers. Together, they formed the Royal Irish Regiment. In 2006, the UDR was given a special award called the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross for its brave service.

Contents

- Why the UDR Was Formed

- Choosing the Name

- How the UDR Was Formed

- How the UDR Was Organized

- Uniforms and Weapons

- UDR Soldiers and Their Families

- Catholic Soldiers Leaving the UDR

- What the UDR Did

- Women in the UDR (Greenfinches)

- Groups Against the UDR

- Soldiers Killed in Service

- Music and Events

- Changes and Joining Another Regiment

- Awards and Honors

- UDR Memorials

- Leaders of the UDR

Why the UDR Was Formed

The UDR was created in 1970, right after a difficult period in Northern Ireland known as The Troubles. Before the UDR, the main security groups were the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC), also known as the "B Specials." Many Catholics felt these groups were not fair and mostly supported one side. This made it hard for Catholics to join them.

In 1969, there were big riots that made it hard for the police to keep order. So, the British Army was sent to help. The USC, which wasn't trained for riot control, also helped the RUC. This led to many problems.

A report called the Hunt Report suggested that the RUC should stop doing military-style jobs. It also said a new local part-time force should be created. This new force would be controlled by the British Army and would replace the USC. The goal was for this new group to be fair to everyone and take military duties away from the police.

The British Government agreed with this report. In November 1969, they started the process to create the UDR. Some people in Parliament worried that members of the old USC would be allowed to join the new UDR.

A team was set up to plan the new force. They suggested having 6,000 men. They also recommended that the new soldiers wear combat uniforms and have a special cap badge with the "red hand of Ulster." The new force's main job was to:

to support the regular forces in Northern Ireland in protecting the border and the state against armed attack and sabotage. It will fulfill this task by undertaking guard duties at key points and installations, by carrying out patrols and by establishing checkpoints and roadblocks when required to do so. In practice, such tasks are most likely to prove necessary in rural areas. It is not the intention to employ the new forces on crowd control or riot duties in cities.

Choosing the Name

When the law to create the Ulster Defence Regiment was being discussed, there was a lot of talk about its name. Some people wanted to change the name to "Northern Ireland Territorial Force." They felt the word "Ulster" was too emotional for many Catholics in Northern Ireland. They argued that "Ulster" was linked to groups that seemed to exclude Catholics. They believed this would stop Catholics from joining the new regiment. One person even said the name "Ulster" would "frighten the Catholics away." They also pointed out that three of Ulster's nine counties were not in Northern Ireland, making the name seem inaccurate.

However, others argued that "Ulster" had been used for other regiments in Northern Ireland before. They also said that most people in Northern Ireland preferred the word "Ulster." The government decided that the word "Ulster" was not that important in the end. So, the name "Ulster Defence Regiment" was kept.

How the UDR Was Formed

The law creating the UDR became official on December 18, 1969. The regiment officially started on January 1, 1970. General Sir John Anderson was chosen as the first leader. He was known as the "Father of the Regiment."

The main office for the UDR was set up in Lisburn. Recruitment began with newspaper ads and a TV commercial. The ads asked for "male citizens of good character" aged 18 to 55. Application forms were sent to all members of the USC, which was closing down.

A team of retired officers checked all applicants. Each person needed two references, and these people were interviewed. All applications were supposed to be checked by the police, but this didn't always happen because so many people applied at first.

On January 13, 1970, seven "training majors" from the regular army arrived. Their job was to get each battalion ready for duty by April 1. They were helped by other army staff.

The UDR used different places for its offices, like old army huts or police stations. Seven battalions were formed at first, covering different counties and the city of Belfast. On April 1, 1970, the UDR officially became part of the British Army.

Finding Officers and NCOs

Each battalion needed a certain number of officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs). The UDR gave instant promotions to suitable people, especially those from the USC or other reserve forces. Officers came from various military backgrounds, including the Royal Navy and even the United States Army. It was a challenge to find enough officers and also keep a balance of Protestant and Catholic members. By March 1971, 18 Catholic officers had joined. All seven battalions were led by former commanders from the USC.

NCOs were often chosen from men who had already been NCOs in other armed forces or the USC. In some cases, the soldiers themselves chose their NCOs. This system sometimes meant that younger NCOs stayed in their roles for a long time, blocking others from getting promoted.

USC Members Joining the UDR

| Battalion | Applications | Accepted | USC | Accepted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antrim (1 UDR) | 575 | 221 | 220 | 93 |

| Armagh (2 UDR) | 615 | 370 | 402 | 277 |

| Down (3 UDR) | 460 | 229 | 195 | 116 |

| Fermanagh (4 UDR) | 471 | 223 | 386 | 193 |

| County Londonderry (5 UDR) | 671 | 382 | 338 | 219 |

| Tyrone (6 UDR) | 1,187 | 637 | 813 | 419 |

| Belfast (7 UDR) | 797 | 378 | 70 | 36 |

| Total | 5,351 | 2,440 | 2,424 | 1,353 |

The response from the "B Specials" (USC members) was mixed. Some felt upset and left, while others applied to join the UDR right away. About 75% of the Tyrone B Specials applied, and 419 were accepted. This meant the 6th Battalion, Ulster Defence Regiment started almost fully staffed. In most battalions, former Specials made up more than half of the soldiers. However, in Belfast, only 10% of UDR members were former Specials.

Some former B Specials were so angry about their group closing that they would boo UDR patrols. In some areas, former USC leaders even told their men not to join the UDR.

Catholic Recruitment

The Belfast Telegraph reported that the first two soldiers to join were a 19-year-old Catholic and a 47-year-old Protestant. The UDR started with 18% Catholic members. Many of these were former regular soldiers who wanted to serve again. However, by 1987, Catholic membership had dropped to 4%.

Recruitment Summary

By March 1970, 4,791 people had applied to join. This included 946 Catholics and 2,424 current or former B-Specials. In total, 2,440 people were accepted.

The number of recruits from both communities did not match the actual population in Northern Ireland. This meant the UDR never became as balanced as Lord Hunt had hoped. Catholics continued to join, but their numbers were always low. The 3rd Battalion, Ulster Defence Regiment had the highest percentage of Catholics, starting at 30%. Some groups within this battalion were entirely Catholic. This led to some complaints that Catholics were being favored for promotions. This was partly because many soldiers from a local army reserve unit, which had closed, joined the UDR together in the Newry area.

By April 1, 1970, the UDR had only 1,606 soldiers, far fewer than the 4,000 they wanted. So, the UDR started its duties understaffed. However, the regiment continued to grow. In 1973, numbers reached 9,100 (all part-time). By the time it merged, the UDR had about 2,797 full-time soldiers and 2,620 part-time soldiers.

How the UDR Was Organized

Unlike the USC, which was controlled by the local government, the UDR was directly commanded by the head of the British Army in Northern Ireland. A special council with three Protestant and three Catholic members was formed to advise on UDR policies, especially recruitment.

The regiment was led by a regular army brigadier. Battalions were initially led by former USC commanders. These were experienced military men, but some were past retirement age. Over time, regular army officers took over these roles. By the time the UDR merged, about 400 regular army officers had served in these positions.

A newspaper called "Defence" was published for the regiment. Commanders used it to share information.

Battalion Structure

The first seven battalions made the UDR the largest infantry regiment in the British Army at that time. Two years later, four more were added, bringing the total to eleven.

In 1972, the UDR had 11 battalions and 59 companies. Most of these were led by regular army officers. The UDR also had full-time soldiers who guarded bases and did office work. Most soldiers were part-time. Their main jobs were guarding important places, patrolling, watching for trouble, and setting up checkpoints. They did not work in the busiest city areas and were not allowed to get involved in crowd control. Soldiers carried rifles or sub-machine guns. At that time, the regiment had 7,910 members.

In 1976, the UDR started adding full-time groups called "Operations Platoons." These groups worked 24 hours a day. By the late 1970s, there were sixteen such platoons. Eventually, these platoons grew into full companies, and full-time UDR soldiers took over their own guard and office duties.

The number of full-time soldiers eventually became more than half of all UDR personnel.

By 1990, the UDR had 3,000 part-time and 3,000 full-time soldiers. About 140 regular army personnel held key leadership and training roles. The full-time soldiers were so well-trained that they could work like regular soldiers. Sometimes, regular army units even worked under the UDR's command.

UDR soldiers were spread out in smaller bases, usually platoon or company size. Battalion headquarters were often in the main town of a county. These bases became very busy after 6 PM when part-time soldiers arrived for evening duties. After 1976, many battalion headquarters had full-time companies that kept a 24-hour presence in their assigned areas.

For example, the 2 UDR battalion in Armagh had a mix of full-time and part-time companies. These companies were based in different towns and worked various hours, from 9 AM to 5 PM for administration to 24-hour shifts for full-time soldiers.

Smaller units kept in touch with their patrols and headquarters using radios. Often, female soldiers (called Greenfinches) operated these radios. This could be very tense when patrols came under attack, and the Greenfinches had to relay "contact reports."

Uniforms and Weapons

Uniforms

In the early days, the UDR had shortages of equipment and uniforms. Soldiers sometimes used old World War II weapons and uniforms. Many were older veterans, which earned them the nickname "Dad's Army," like the Home Guard in World War II.

Once equipment was available, male soldiers wore camouflage jackets and a dark green beret. The beret had a gold-colored harp badge with a crown on top. This badge was a copy of the Royal Ulster Rifles badge. Female "Greenfinch" soldiers wore combat jackets and dark green skirts with the UDR beret and badge. For special events, men wore a dark green version of the British Army's formal uniform. Women wore a dark green jacket and skirt.

Weapons

At first, the UDR used old World War II weapons like Lee–Enfield rifles and Sten submachine guns. In early 1972, these were replaced with the standard L1A1 Self-Loading Rifle (SLR). Other weapons like Browning pistols, Sterling submachine guns, and Bren light machine guns also became available. They also had some Federal Riot Guns to fire plastic bullets for breaking down doors.

In 1988, the SLRs were replaced by the SA80 rifle. Machine guns were also replaced by the Light Support Weapon. At checkpoints, metal caltrops were used to puncture tires of cars trying to escape.

For personal safety when off duty, some soldiers were given a small pistol. Soldiers who were at very high risk were sometimes allowed to keep their rifles at home. This policy was called "weapons out." However, it was reduced in 1972 because many rifles were stolen by paramilitary groups. The "weapons out" policy was eventually stopped when the SA80 rifle was introduced.

Equipment

Vehicles

The main patrol vehicle was the Land Rover. The UDR also used Shorland armoured cars, which had extra protection. However, Shorlands were not very popular because they were unstable on the road due to their heavy turret. Still, some battalions used them into the 1980s in dangerous areas because of their armor.

Sometimes, the UDR units were moved by Royal Air Force or Army Air Corps helicopters. This allowed them to get to places quickly or to areas where it was too dangerous to use vehicles on the ground.

Boat Patrols

Some battalions used small boats called Dell Quay Dory craft to patrol waterways near the border with the Republic of Ireland. This was to stop weapons from being smuggled across. These boats had machine guns and anti-tank weapons. They were also helped by land-based radar. This led to a small warship being stationed in Carlingford Lough, which helped stop gun-running in that area.

Communication

At first, there weren't enough radios for every patrol. The radios they had didn't work over long distances. So, UDR patrols carried loose change to use in public telephone boxes to report back to base. Later, they received better radios like those used by the regular army. These radios improved over time. Each battalion could talk to other battalions using special radio systems.

Dogs

Search dogs were first provided by the regular army. Later, the UDR formed its own dog section to help with searches for weapons and explosives. One dog handler, Corporal Brian David Brown, and his Labrador dog Oliver, were killed by a bomb in 1986. Corporal Brown was given a medal for his bravery after his death.

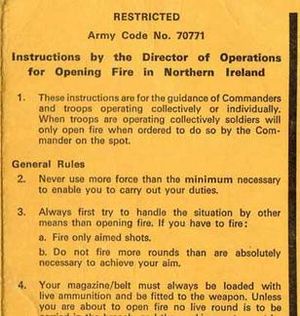

The Yellow Card

All British soldiers, including the UDR, carried small cards with important information. The most important was the Yellow Card. This card explained the rules for when a soldier could open fire.

Soldiers had to know these rules very well. They were told to give warnings to suspects to allow them to surrender. Soldiers could only shoot without warning if it was the only way to protect themselves or others from being killed or seriously hurt. The card was updated in 1980 to say, "Firearms must only be used as a last resort."

UDR Soldiers and Their Families

Training

In 1970, about 25% of new recruits had no military experience. Regular soldiers trained them, helped by experienced recruits.

Part-time soldiers had to train for twelve days and twelve two-hour sessions each year. This included going to an annual training camp. As a reward, soldiers who completed their training received a yearly payment.

Like all British army recruits, training started with basic battle skills. They also learned how to shoot accurately.

Part-time and full-time soldiers had to attend a seven-day annual camp. These camps were in places like Warcop in England or Ballykinler in Northern Ireland. These camps provided intense training and also allowed soldiers to relax away from their patrol areas.

From 1975, special search teams were created. They looked for hidden weapons and explosives in the countryside and empty buildings. These hidden items were sometimes booby-trapped, so soldiers had to be very careful.

On July 2, 1979, the UDR Training Centre opened at Ballykinlar. New recruits took a four-week course. It included physical training, marching, assault courses, shooting, patrol procedures, map reading, radio use, first aid, and legal responsibilities. The center also offered courses for officers and NCOs, and training in surveillance and photography.

By 1990, the UDR Training Centre was in charge of all military training in Northern Ireland. It ran courses for the regular army and other units.

Family Life

Sometimes, several members of the same family joined the UDR. Husbands, wives, sons, daughters, and even grandparents served together. This created a strong team spirit. However, it also created problems. Once someone in a family joined the UDR, the whole household, including children, had to learn about personal safety. Soldiers worked long hours and had to give up a normal family life.

On duty, family members had to be placed in different patrols and vehicles. This was to prevent an entire family from being killed or wounded if one unit was attacked. In 1975, there were 84 married couples and 53 family groups of three or more serving in the UDR.

UDR soldiers lived in their own homes, not in army housing. Many lived in areas that were mostly Protestant or Catholic. This made them easy targets for local groups. In 1972–73, there were many threats against UDR soldiers from both sides. Most of these threats came from Protestants against other Protestants, trying to get information or persuade soldiers to join loyalist groups. These threats included letters, phone calls, attacks, and damage to homes.

Some UDR soldiers lived in very dangerous areas. For example, Private Sean Russell was killed at home in front of his family.

Catholic Soldiers Leaving the UDR

In 1970–71, Catholics made up about 36% of the population and 18% of the UDR. By the end of 1972, the number of Catholics in the UDR had dropped to 3% and stayed low. There were several reasons for this.

In the early years of the conflict, relations between the Catholic community and the Army became difficult. This was due to events like the Falls Curfew, internment (arresting people without trial), Bloody Sunday, and Operation Motorman. There were also many complaints that UDR soldiers treated Catholics unfairly at checkpoints and during house searches.

Many Catholic soldiers left the regiment because of pressure and threats from their own community. The IRA also targeted Catholic soldiers for assassination. Some Catholics in the UDR also reported being threatened by Protestant fellow soldiers. Other Catholics resigned because they felt the Army was treating their community harshly, especially after internment began. The Belfast Telegraph reported that 25% of the UDR's Catholics resigned in 1971. By the end of 1972, most had left or stopped showing up for duty.

Senior officers tried to stop Catholics from leaving. They allowed battalion commanders to appear on TV and appealed to religious and political leaders. They also added extra security for soldiers. The UDR's second-in-command, Colonel Kevin Hill, was Catholic, as was his successor. However, these appointments sometimes made Protestants uneasy.

By 1981, less than 2% of UDR soldiers were Catholic. Most of these were former British Army members from non-Irish backgrounds who had settled in Northern Ireland.

What the UDR Did

The UDR was part of the British Army, but its duties were only in Northern Ireland. This was called "Home Service."

The main job of the UDR was to help the police by "guarding key points and installations, to carry out patrols and to establish check points and road blocks against armed guerrilla-type attacks." Patrols and checkpoints on roads were meant to stop paramilitary groups and make law-abiding people feel safer. Some believed the UDR was initially formed just to please one side and was given less important jobs, like guarding water reservoirs.

The UDR's first mission was with the 2nd and 6th battalions. About 400 soldiers worked along the border to stop weapons from entering Northern Ireland. Since most soldiers were part-time, their presence was mainly felt in the evenings and on weekends. They were called out for major operations, like Operation Motorman, to help the police and army. As the UDR got more full-time soldiers, it took over duties that the police or regular army used to do. By 1980, the UDR had tactical responsibility for 85% of Northern Ireland, supporting the police.

1974 Ulster Workers Council Strike

The first Ulster Workers' Council strike happened in May 1974. This was a big test for the UDR and the police. The UDR was not officially called out, but some units were sent to different areas. For example, 3 (County Down) UDR was sent to South Tyrone and South Fermanagh. This was because loyalist groups had carried out bombings, and authorities expected the IRA to strike back.

Even though there was no official call-out, UDR soldiers went to their bases ready for duty. They were frustrated because they couldn't take direct action against the strikers. Their orders were to "stand back and observe." A patrol from 7 UDR stopped loyalists from throwing stones at regular troops. In another case, UDR soldiers convinced people to remove barricades that were stopping them from getting to their base.

Some UDR soldiers even helped man the barricades alongside loyalist groups. These were soldiers who lived in areas controlled by these groups and had been threatened. Soldiers who didn't help were sometimes stopped from getting to duty, and their cars and homes were damaged.

There were two attempts by loyalists to turn UDR units against the government, but both failed.

Units from 7 UDR guarded important places like shipyards and power stations. Drivers from other UDR battalions helped with transport. Eventually, UDR and regular army units forcibly removed the barricades.

Before the strike, some army commanders worried about the UDR's loyalty. But after the strike, one Brigadier said, "During the strike the UDR came of age."

Ulsterisation

Ulsterisation was a British Government plan to reduce the number of regular British Army troops in Northern Ireland. The idea was to have local forces, like the UDR, take on more of the front-line duties. This was also called "normalisation" or "police primacy." The media called it "Ulsterisation." The goal was for people in Northern Ireland to be policed by their own people.

A report in 1976 suggested:

- More RUC and RUC Reserve members.

- More full-time UDR soldiers to take over from the regular Army.

- The UDR to have a 24-hour military presence.

One main result of Ulsterisation was the creation of the "Province Reserve UDR" (PRUDR). This meant that UDR companies would take turns working anywhere in Northern Ireland, though often this meant in South Armagh.

Women in the UDR (Greenfinches)

In the early days, female military police helped search female suspects. But there weren't enough of them. So, in 1973, a law was passed to allow women to join the UDR. On August 16, 1973, Major Eileen Tye became the "Commander Women" for the UDR. By September, 352 women had joined. This was 20 years before other parts of the regular army fully included women.

At first, the women wore old World War II uniforms, including skirts. Many were unhappy with this. Eventually, they were allowed to wear full combat uniforms. They also wore a silk scarf in their battalion's color.

A team of instructors trained the women in a one-week course. It covered marching, army organization, map reading, searching women and vehicles, radio use, and basic first aid. After a year, experienced Greenfinches took over as instructors.

The first women to join were often from professional backgrounds. Some were wives of UDR soldiers or regular army soldiers stationed in Northern Ireland. For former female soldiers or wives of male ex-soldiers, being a Greenfinch seemed like a familiar career.

City-based battalions were slower to accept women at first, but everyone soon saw the value of having women on patrols. Over time, women's roles expanded. Their higher-pitched voices were found to be better for radio communication than men's.

Some women were trained to use "Sea Watch" radar to help boat patrols.

Initially, a part-time female officer supervised the women in each battalion. Later, women came under the command of the company officer. In later years, some women became battalion officers or company commanders.

It took several years for UDR bases, which were mostly male, to adapt to having female soldiers, especially for changing and toilet facilities.

The nickname "Greenfinch" came from the army's radio codewords. Male soldiers were "Greentop," and women were "Greenfinch." This nickname is still used today for women in the Royal Irish Regiment.

The number of women soldiers reached its highest point in 1986, with 286 full-time and 530 part-time members. From 1978 onwards, there were always at least 700 women serving.

Women's Duties

Greenfinches helped stop terrorists from using women and children in their activities. On patrol, they searched for explosives, weapons, and documents. They also drove patrol vehicles, operated radios, and interviewed people. In barracks, women did office work, catering, and store-keeping. This freed up male soldiers for operational duties.

Training for Women

Women soldiers had to pass yearly tests to keep their rank and pay. If they failed, their pay would be lowered. They received regular training specific to their roles, including searching, map reading, first aid, radio use, personal safety, and recognizing terrorists. They were also advised to stay fit.

Although Greenfinches were not armed on duty, they were trained to fire a full range of weapons. They also learned how to make a weapon safe when dealing with injured soldiers.

Some Greenfinches were given personal protection weapons if they were considered to be at high risk.

Pregnancy, Marriage, and Pay

Rules about pregnancy, marriage, and pay also affected Greenfinches. Married women needed written permission from their husbands to join. Those with children had to sign a paper confirming childcare arrangements.

Army rules meant Greenfinches would be discharged in their fourth month of pregnancy. If they returned after maternity leave, they had to retake the basic training course. Their previous service did not count towards medals or promotions. Some commanders tried to help by giving women long-term leave instead of discharging them.

In 1990, the European Court ruled against the Ministry of Defence. This led to compensation for 78 former Greenfinches. After this, all British servicewomen were allowed 48 weeks of unpaid maternity leave and could return to duty without conditions.

A study in 1988 showed that half of the women serving were married, and 42% were mothers. Two-thirds of their children were infants or of school age.

Women Casualties

Four Greenfinches were killed while serving between 1974 and 1992. The first was Private Eva Martin, who died on May 3, 1974, during an attack by the PIRA. She was the first female from the security forces to die in the Troubles.

Groups Against the UDR

When the UDR was being planned, the main threat was the Irish Republican Army (IRA). After a split, the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) was formed in December 1969, just before UDR recruitment began.

The PIRA remained the UDR's main focus. However, other groups also caused violence, such as the Official Irish Republican Army (OIRA) and the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA). Loyalist groups like the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) (which used the name Ulster Freedom Fighters) also threatened peace. As the PIRA's campaign continued, it and other groups increasingly targeted UDR soldiers and other law enforcement members.

Soldiers Killed in Service

Between April 1, 1970, and June 30, 1992, a total of 197 UDR soldiers were killed while on active duty. Another 61 were killed after they had left the UDR.

Music and Events

Each UDR battalion had pipers who also formed a main pipe band called the Pipes & Drums of the Ulster Defence Regiment. Their uniform was traditional for Irish pipers, with a saffron kilt and a dark green jacket.

In June 1986, the regiment held its only public show, called a tattoo, at a rugby ground in Belfast. About 12,000 people attended. Attractions included parachute teams, Greenfinches rappelling, UDR dogs, a fake ambush, and music from the UDR pipe band and other army bands.

Changes and Joining Another Regiment

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the United Kingdom decided to make its armed forces smaller. The army wanted to reduce its size from 160,000 to 110,000 soldiers. The head of the British Army in Northern Ireland saw this as a chance to improve the UDR's image and career opportunities. He decided to merge the UDR with the Royal Irish Rangers. This was the first time part-time soldiers would be fully included in the regular army. The hope was that this merger and new name would give the UDR a fresh start, as it had faced some criticism. The Rangers also recruited from the South of Ireland, including many Catholics, which would help.

The plan was approved in 1991. It suggested:

- The two Royal Irish Rangers battalions would combine into one.

- The nine UDR battalions would be reduced to seven and called "Home Service."

- The part-time soldiers would remain in the Home Service part.

- The new regiment would be called the Royal Irish Regiment. This name had been used by famous Irish infantry regiments before.

In return, the UDR would receive:

- A royal title.

- A direct link to famous battles in Irish history.

These plans were generally welcomed by senior officers. However, soldiers worried that this was a step towards the regiment being completely disbanded. Political parties in Northern Ireland also protested.

When it merged in 1992, the UDR had been on active service longer than any regiment since the Napoleonic Wars. It had been on duty every day from its creation until its merger.

Awards and Honors

The most important award given to the Ulster Defence Regiment was the Conspicuous Gallantry Cross. The Queen awarded it on October 6, 2006. This award meant the regiment would be known as "The Ulster Defence Regiment CGC." During the ceremony, the Queen praised the regiment, saying:

- "Your contribution to peace and stability in Northern Ireland is unique." "Serving and living within the community had required "uncommon courage and conviction". "The regiment had never flinched despite suffering extreme personal intimidation. Their successes had "come at a terrible price, many gave their lives. Today you have cause to reflect on the fine achievements, while remembering the suffering". "The Home Service Battalions of the RIR and the UDR which had preceded them won the deepest respect throughout the land." So that their actions would always be remembered, the CGC was awarded to the RIR/UDR "as a mark of the nation's esteem" with the citation, "This award is in recognition of the continuous operational service and sacrifice of the Ulster Defence Regiment and the Royal Irish Regiment in Northern Ireland during Operation Banner."

In total, 953 individual UDR soldiers received awards. These included 12 Queen's Gallantry Medals and 2 Military Medals. Most UDR soldiers received "service" or "campaign" medals, such as:

- The General Service Medal with "Northern Ireland" bar.

- The Ulster Defence Regiment Medal.

- Northern Ireland Home Service Medal.

- The Accumulated Campaign Service Medal.

- The Medal for Long Service and Good Conduct (Ulster Defence Regiment).

The rules for UDR-specific long service medals were complex, so not many were given out. Only 1,254 of the 40,000 soldiers who served received the UDR medal.

The most decorated UDR soldier was Corporal Eric Glass, who received two medals for bravery. Even after being badly injured in an attack, he managed to survive and kill one of his attackers.

In 1987, the regiment asked the Queen for permission to have "colours" (special flags). This was granted in 1991, and the Queen herself presented the colours to five battalions. This was a great honor, usually only given to regiments where she is the Colonel in Chief.

By May 2010, 232 Elizabeth Crosses and Memorial Scrolls had been given to the families of UDR personnel who died because of their military service.

- Medals of the Ulster Defence Regiment

Freedoms

Several towns and cities in Northern Ireland, including Belfast, honored the UDR by giving them "freedoms." This is a special honor given to military units.

Wilkinson Sword of Peace

The 7th/10th (City of Belfast) Battalion received the Wilkinson Sword of Peace in 1990. This award recognized their work in improving community relations.

UDR Memorials

The UDR Memorial, Lisburn

A memorial to the UDR was built in Lisburn. It was made to honor the sacrifices of the soldiers, both men and women, from all backgrounds in the UK. The memorial is a 19-foot bronze sculpture. It shows a male UDR soldier and a female "Greenfinch" on duty. The statues stand on a large granite base.

The UDR Memorial Trust is responsible for the memorial. It is located in Market Square, Lisburn. This memorial is in addition to the UDR Roll of Honour, which is near the Lisburn War Memorial. The Roll of Honour lists UDR personnel from the Lisburn area who died in the conflict.

The memorial statues were unveiled on June 12, 2011. At the ceremony, the Trust chairman said that while some members did bad things, nearly 50,000 people did good things. He said they were ordinary people who wanted to do their best for their country.

National Arboretum Memorial

On April 28, 2012, a memorial to the UDR was unveiled at the National Memorial Arboretum. This memorial is a 6-foot granite monument. Memorial trees were also planted for UDR soldiers who were killed after leaving the regiment. Trees for those killed while serving had already been planted. About 100 UDR families attended the event, along with government officials. A parade led by the band of the 1st Battalion Royal Irish Regiment marched to the monument.

- A selection of the memorials to the fallen of the UDR found in churches, High Streets and memorial gardens in Northern Ireland and England.

-

Poppy crosses for the fallen, Belfast Cenotaph.

Leaders of the UDR

(Also known as "Brigadier UDR")

- Brigadier Logan Scott-Bowden (1970–1971)

- Brigadier Denis Ormerod (1971–1973) (First Catholic Commander UDR)

- Brigadier Harry Baxter (1973–1976) (First Irish Commander)

- Brigadier Mervyn McCord (1976–1978)

- Brigadier David Millar (1978–1980)

- Brigadier Pat Hargrave (1980–1982)

- Lieutenant General Sir Peter Graham (1982–1984)

- Brigadier Roger St Clair Preston (1984–1986)

- Brigadier Michael Bray (1986–1988)

- Brigadier Charles Ritchie (1988–1990)

- Brigadier Angus Ramsay (1990–1992)

Colonels Commandant

- General Sir John Anderson (1969–1977) (1st Colonel Commandant).

- Brigadier Harry Baxter (1977–1986).

- General Sir David Young (1986–1991).

- General Sir Charles Huxtable (1991–1992). He continued as Colonel Commandant of the Royal Irish Regiment until 1996.

Regimental Colonel

Colonel Sir Dennis Faulkner (1982–1992)

| Stephanie Wilson |

| Charles Bolden |

| Ronald McNair |

| Frederick D. Gregory |