Ulster Special Constabulary facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Ulster Special Constabulary |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Common name | B Specials |

| Abbreviation | USC |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | October 1920 |

| Dissolved | 31 March 1970 |

| Superseding agency | UDR |

| Employees | 5,500 |

| Volunteers | 26,500 |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

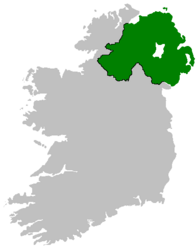

| National agency | Northern Ireland |

| Operations jurisdiction | Northern Ireland |

|

|

| Map of Ulster Special Constabulary's jurisdiction | |

| Size | 13,843 km2 (5,345 sq mi) |

| General nature | |

The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC), often called the "B-Specials" or "B Men", was a special police force in what is now Northern Ireland. It was set up in October 1920, just before Ireland was divided. This armed group worked like a military force and was called into action during emergencies, such as wars or times of unrest. They played a key role during the Irish War of Independence (early 1920s) and the IRA Border Campaign (1956-1962).

During its time, 95 members of the USC died while on duty. Most of these (72) were killed in fights with the IRA between 1921 and 1922. Eight more died during the Second World War. The remaining members died in accidents.

The force was made up almost entirely of Ulster Protestants. Because of this, many Catholics did not trust them. The USC was involved in some serious incidents against Catholic civilians during the 1920–22 conflict. People who supported Unionism generally believed the USC helped protect Northern Ireland from threats and outside attacks.

The Special Constabulary was officially ended in May 1970. This happened after the Hunt Report suggested changing Northern Ireland's security forces. The goal was to encourage more Catholic recruits and make the police less like a military group. Many of its duties and members were then taken over by the Ulster Defence Regiment and the Royal Ulster Constabulary.

Contents

Why the USC Was Formed

The Ulster Special Constabulary was created during a time of big changes in Ireland. People were fighting for Irish independence, and the country was about to be divided.

The Irish War of Independence (1919–21) saw the Irish Republican Army (IRA) launch attacks to gain independence for Ireland. In Ireland's northeast, Unionists strongly disagreed with this idea. They wanted to stay part of the United Kingdom. When it became clear that the British government would grant independence to most of Ireland, Unionists focused on creating Northern Ireland. This new region would include six counties where Unionists were the majority.

Two main reasons led to the creation of the Ulster Special Constabulary:

- Unionist Control: Unionist leaders, like Sir James Craig, wanted to have control over government and security in Northern Ireland before it was officially formed.

- Rising Violence: Violence in the north increased after the summer of 1920. The IRA began attacking police and government offices. There were also serious riots between Catholics and Protestants in Derry and Belfast, which caused many deaths.

With regular police and soldiers busy fighting in other parts of Ireland, Unionists wanted a local force to deal with the IRA. Sir James Craig suggested a new "volunteer constabulary" made up of "loyal population" members. He wanted it organized "on military lines" and armed. He also suggested using the Ulster Volunteers (UVF), a Unionist group formed in 1912, for this purpose. Many UVF members joined the new USC.

The British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, liked the idea of a volunteer police force. It would free up other police and military forces, it was cheap, and it didn't need new laws. So, the formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary was announced on October 22, 1920.

Who Joined the USC?

The USC was mostly made up of Protestants and Unionists. This happened for several reasons. Some informal "constabulary" groups already existed in Protestant areas. For example, the Ulster Unionist Labour Association had its own "unofficial special constabulary" in Belfast.

In April 1920, Captain Sir Basil Brooke (who later became Prime Minister of Northern Ireland) started a group called "Fermanagh Vigilance." This group aimed to protect against IRA attacks. Many existing Protestant groups were encouraged to join the new USC. They often already had weapons, especially from the Ulster Volunteers.

Nationalists pointed out that the USC was almost entirely Protestant. They claimed the government was arming Protestants to attack Catholics. Some Special Constables were even accused of rioting and looting. Many UVF units joined the new Constabulary, and their leaders were given important roles.

Efforts were made to get more Catholics to join the force, but these largely failed. One reason was that Catholic members were often targeted by the IRA. The Nationalist Party and Ancient Order of Hibernians also told their members not to join. The IRA even warned that any Catholics who joined the Specials would be seen as traitors.

How the USC Was Organized

The British government paid for and equipped the USC, and it was controlled by the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). The USC had about 32,000 men, divided into four main groups, all of whom were armed:

- A Specials: These were full-time, paid members. They worked with regular RIC officers but stayed in their home areas. They often worked at checkpoints. There were about 5,500 A Specials.

- B Specials: These were part-time, unpaid members. They usually worked one evening a week under their own leaders. They served wherever the RIC served and formed mobile groups. There were about 19,000 B Specials.

- C Specials: These were unpaid, non-uniformed reserve members. They were usually older and did guard duties near their homes. There were about 7,500 C Specials.

- C1 Specials: These were non-active C class members who could be called out in emergencies. This group was formed in late 1921. It included local Unionist groups like the Ulster Volunteers, bringing them under government control.

The units were organized like military groups. A platoon (a small group) had two officers, a Head Constable, four sergeants, and sixty special constables.

By July 1921, over 3,500 A Specials and almost 16,000 B Specials had joined. By 1922, the numbers grew to 5,500 A Specials, 19,000 B Specials, and 7,500 C1 Specials. Their jobs included fighting IRA attacks in cities and rural areas. They also stopped border crossings, arms smuggling, and helped catch people trying to escape.

Concerns About the USC

From the very beginning, many people criticized the USC. This criticism came mostly from Irish nationalists and the government in Dublin. Some British military and government officials also had concerns. They worried that the USC would be a force that caused division and favored one side.

In the British Parliament, Joseph Devlin, a Nationalist Party leader, clearly stated his feelings: "The Chief Secretary is going to arm pogromists to murder Catholics...we would not touch your special constabulary with a 40 foot pole."

Sir Nevil Macready, the head of the British Army in Ireland, and Henry Hughes Wilson argued that creating a special constabulary was dangerous. Wilson warned that forming a biased police force "would mean; taking sides, civil war and savage reprisals."

The Irish nationalist newspapers were even stronger in their criticism. The Fermanagh Herald wrote that these "Special Constables" would be "nothing more and nothing less than the dregs of the Orange lodges, armed and equipped to overawe Nationalists and Catholics."

Training, Uniforms, and Weapons

The training for the Specials was not always the same. In Belfast, they were trained much like regular police. In rural areas, the USC focused on fighting guerrilla groups. In 1922, B Specials received two weeks of training, and A Specials initially had six weeks. This amount of training was often not enough for the serious conflicts they faced.

At first, uniforms were not available. B Specials wore their regular clothes with an armband to show they were Specials. Uniforms became available in 1922. They looked like the uniforms of the RIC/RUC, with high-collared jackets. Rank badges were worn on the right forearm of the jacket.

Special Constables were armed with Webley .38 revolvers, Lee–Enfield rifles, and bayonets. By the 1960s, Sten and Sterling submachine guns were also used. In most cases, constables kept these weapons and ammunition at home. This allowed them to be called out quickly without needing to get weapons from a central storage place.

'A Special' platoons were fully mobile. They used a Ford car for the officer in charge, two armored cars, and four Crossley Tenders (trucks) for their sections. B Specials usually walked but could get vehicles from the police pool.

Role in the Irish War of Independence (1920–22)

The USC's involvement in the Anglo-Irish War gave the Northern Ireland government its own local force to fight the IRA. Using the Specials to help the RIC also allowed over 20 police stations in rural areas to reopen. These stations had been closed due to IRA attacks. The cost of keeping the USC in 1921–22 was £1,500,000.

Their actions towards the Catholic population were criticized many times. In February 1921, Specials and UVF members burned ten Catholic homes in Roslea after a Special Constable was shot and wounded. After a Special Constable died near Newry in June 1921, it was claimed that Specials and an armed crowd burned 161 Catholic homes and killed 10 Catholics. An investigation suggested that the Special Constabulary "should not be allowed into any locality occupied by people of an opposite denomination."

After a truce between the IRA and the British in July 1921, the USC was temporarily stood down. However, the force was called back into action in November 1921, when security powers were given to the Northern Ireland Government.

Michael Collins, a leader of the Irish Free State, planned a secret guerrilla campaign against Northern Ireland using the IRA. In early 1922, he sent IRA units and weapons to the northern border areas. On December 6, the Northern authorities ended the truce with the IRA.

The Special Constabulary acted as both a police support and an army under Northern Ireland's control. By including the former UVF as C1 Specials, the Belfast government had a large group of experienced troops ready for more fighting.

1922: Border Conflict and Incidents

The USC was most active in the first half of 1922. During this time, a low-level war took place along the new Irish border between the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland.

The Anglo-Irish Treaty had divided Ireland into the Irish Free State and Northern Ireland. The IRA, even though it was split over the Treaty, continued its attacks in Northern Ireland. This happened with the help of Michael Collins and Liam Lynch, leaders of different IRA groups.

The renewed IRA campaign involved attacking police stations, burning buildings, and a large attack into Northern Ireland. They occupied Belleek and Pettigo in May–June. This attack was stopped after heavy fighting, including the British Army using artillery.

The British Army was only used in the Pettigo and Belleek actions. So, the main job of fighting this border conflict fell to the Special Constabulary. Forty-nine Special Constables were killed during this "Border War." Their biggest loss was at Clones in February 1922. A patrol entered the Free State and refused to surrender to the local IRA. Four Specials died and eight were wounded in the fight.

Besides fighting the IRA, the USC may have been involved in attacks on Catholic civilians. These were often in response to IRA actions. For example, in Belfast, the McMahon Murders in March 1922 killed six Catholics. A week later, the Arnon Street killings killed another six. On May 2, 1922, Special Constables killed nine Catholic civilians in the area. This was in revenge for the IRA killing six policemen.

The conflict slowly ended in June 1922, when the Irish Civil War began in the Free State. Many IRA activists in the North were arrested.

People have different opinions about the USC's role in this conflict. Unionists say the Special Constabulary "saved Northern Ireland from anarchy" and "subdued the IRA." Nationalist writers, however, say that the USC's treatment of the Catholic community, including "widespread harassment and a significant number of reprisal killings," made nationalists permanently distrust the USC and the Northern Irish state.

From the 1920s to the 1940s

After the conflict of 1920–22, the Special Constabulary was reorganized. The regular Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) took over normal police duties.

The 'A' and 'C' categories of the USC were removed. Only the B-Specials remained. They worked as a permanent reserve force, armed and uniformed like the RUC.

The Special Constabulary was called out in Belfast during the 12 July period in 1931. This happened after sectarian riots broke out. The B Specials helped the RUC with normal duties, allowing the RUC and British Army to deal with the unrest.

In 1936, a British group called the National Council for Civil Liberties described the USC as "nothing but the organised army of the Unionist party."

During the Second World War, the USC was used as part of Britain's Home Guard. Unusually, this force was placed under police command, not the British Army.

The IRA Border Campaign (1950s)

Between 1956 and 1962, the Special Constabulary was again called into action. Their job was to fight a guerrilla campaign launched by the IRA.

Property damage during this time cost £1 million. The total cost of the campaign to the UK government was £10 million. Historian Tim Pat Coogan said that the USC was "the rock on which any mass movement by the IRA in the North has inevitably floundered." Six RUC officers and eleven IRA members were killed in this campaign, but no Special Constables died.

The IRA ended their campaign in February 1962.

1969 Deployment and Disbandment

The USC was used in 1969 to support the RUC during the 1969 Northern Ireland riots. The B Specials' actions during these events led to their disbandment the following year.

Northern Ireland faced unrest because of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association's protests for equal rights for Catholics. The USC was called in when the regular RUC was overwhelmed by riots in Derry (known as the Battle of the Bogside). The Civil Rights Association called for protests elsewhere, causing violence to spread across Northern Ireland, especially in Belfast.

The USC was mostly kept in reserve in July and only used with hesitation in August. The British Army commander in Northern Ireland refused to get involved until the Belfast government used "all the forces at its disposal." This meant the B Specials had to be deployed, even though they were not trained for riot control. It was clear that using the B Specials in such situations was not suitable: "The 'Specials', untrained for such a job, contained no Catholic members, were inevitably regarded as sectarian, and their presence tended to heighten rather than lower tension in Catholic areas."

In Belfast, the USC successfully brought order to the mostly Protestant Shankill area. They performed their patrol duties without weapons there. However, on August 14, they did not stop Protestants who attacked Catholic areas like Dover and Percy streets. Instead, they "fought back" Catholics there.

USC Shootings

The USC's most controversial actions in the 1969 riots happened in smaller towns. There, the Special Constabulary was the main force responding to the riots. The Specials, who were armed and not trained for riot duty, used deadly force several times.

The USC shot and wounded people in Dungiven and Coalisland. In Dungannon, they killed one person and wounded two. The later Scarman Tribunal found that the shooting in Dungannon was "a reckless and irresponsible thing to do."

When Jack Lynch, the leader of Ireland, moved Irish Army troops to the border, platoons of Specials were sent to guard border police stations.

Following these disturbances, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson announced that the B Specials would be "phased out." The British Government ordered three reports into the police response to the 1969 riots. These reports eventually led to the Ulster Special Constabulary being disbanded.

The Cameron Report

Sir John Cameron was asked to write a report on the unrest in Northern Ireland.

He found some evidence that members of the USC also belonged to loyalist paramilitary groups. He said this "we consider highly undesirable." He also noted that even though "recruitment is open to both Protestant and Roman Catholic: in practice we are in no doubt that it is almost if not wholly impossible for a Roman Catholic recruit to be accepted." The Cameron Report described the B-Specials as "a partisan and paramilitary force recruited exclusively from Protestants."

Cameron suggested that the USC's purpose as a reserve police force and a counter-insurgency force should be made clearer in recruitment and training. This, he hoped, would make it more appealing to Catholics.

The Scarman Report

Justice Scarman, in his report on the riots, criticized the RUC's senior officers and how the B Specials were used in civil disturbances. He said they were not trained for such situations, which sometimes made things worse. However, he also noted that the B Specials were the only reserve available to the RUC and that there was no other quick way to reinforce the overwhelmed RUC. He praised the Specials when he felt it was deserved.

Scarman concluded that the idea of a partisan force working with Protestant mobs to attack Catholics was "devoid of substance, and we reject it utterly."

Scarman also criticized the RUC's command for sending armed Special Constables into areas where their presence would "heighten tension." He was sure that Catholics "Totally distrusted them, who saw them as the strong arm of the Protestant ascendancy."

Scarman concluded that it would have been very difficult for Catholics to join in 1969, even if they had tried.

The Hunt Report

The demand to abolish the B Specials was a key goal of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Movement in the late 1960s.

On April 30, 1970, the USC was finally stood down, based on the recommendations of the Hunt Committee Report. Hunt believed that the perceived bias of the Special Constabulary, whether true or not, needed to be addressed. Another major concern was using a police force for military-style operations. His recommendations included:

- A locally recruited part-time force, controlled by the British Army commander in Northern Ireland, should be created. This force, along with a police volunteer reserve, should replace the Ulster Special Constabulary.

Disbandment

The Ulster Special Constabulary was officially ended in May 1970. Some people argue that their failure to handle the 1969 disturbances was because the Northern Ireland government did not update their equipment, weapons, training, or approach to the job.

When the USC was disbanded, many of its members joined the newly formed Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR). The UDR was a part-time security force that replaced the B Specials. Unlike the Special Constabulary, the UDR was under military control. Other B Specials joined the new Part Time Reserve of the RUC. The USC continued its duties for a month after the UDR and RUC Reserve were formed, to give the new forces time to get organized.

During the final handover to the Ulster Defence Regiment, the B Specials had to give back their weapons and uniforms. Despite government concerns, every single uniform and weapon was returned.

After the Hunt report was put into action, most B Men had their last night of duties on March 31, 1970. On April 1, 1970, the Ulster Defence Regiment began its duties. Initially, the Regiment had 4,000 part-time members. The new special constabulary, the RUC Reserve, which replaced the B-Specials, started with 1,500 members.

Lasting Impact

Since it was disbanded, the USC has become a very important part of Unionist history. However, in the Nationalist community, they are still seen as the Protestant-only, armed part of the Unionist government. They are "associated with the worst examples of unfair treatment of Catholics in Northern Ireland by the police force." An Orange lodge (a Protestant organization) was formed to remember the disbandment of the force, called "Ulster Special Constabulary LOL No 1970." An Ulster Special Constabulary Association was also set up soon after the disbandment.

Notable Members

- Major Kenneth Wiggins Maginnis, Baron Maginnis of Drumglass

See also

- Auxiliary constable

- Auxiliary police

- Alexander Robinson

- Special constable

- Special constabulary

- Special police

- Good Friday Agreement

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |