European Court of Human Rights facts for kids

Quick facts for kids European Court of Human Rights |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Established |

|

| Jurisdiction | 46 member states of the Council of Europe |

| Location | Strasbourg, France |

| Coordinates | 48°35′48″N 07°46′27″E / 48.59667°N 7.77417°E |

| Composition method | Appointed by member states and elected by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe |

| Authorized by | European Convention on Human Rights |

| Appeals to | Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights |

| Number of positions | 46 judges, one from each of the 46 member states |

| President | |

| Currently | Síofra O'Leary |

| Since | 2013 (judge), 2020 (President) |

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) is a special court in Europe. It's also called the Strasbourg Court. It helps make sure that countries follow the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). This court listens to people who say a country has broken rules about human rights. These rules are listed in the ECHR agreement. The court is located in Strasbourg, France.

The court started in 1959 and heard its first case in 1960. People, groups, or even other countries can bring cases to the court. Besides making decisions, the court can also give advice. The ECHR agreement was created by the Council of Europe. All 46 member countries of the Council of Europe have signed this agreement. The court tries to understand the ECHR in a modern way. This means it looks at today's world when making decisions.

Many experts think the ECtHR is the best human rights court in the world. However, sometimes countries do not follow the court's decisions.

Contents

- How the Court Started and Works

- The Court and the Council of Europe

- Member Countries

- Judges

- Court Leadership and Management

- Court's Authority

- How Decisions Affect Everyone

- Court Process and Decisions

- Fair Compensation

- How the Court Works with Other Courts

- How Well the Court Works

- Awards and Recognition

- See also

- Images for kids

How the Court Started and Works

On December 10, 1948, the United Nations created the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This document aimed to set a worldwide standard for human rights. It was a very important step. But it did not have a way to make sure countries followed it.

In 1949, the twelve countries that started the Council of Europe began working on the European Convention on Human Rights. They used ideas from the Declaration. But this new agreement had a key difference. For European countries that signed it, there would be a court. This court would make sure they respected their citizens' basic rights.

The court officially began on January 21, 1959. Its first members were chosen by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. At first, it was harder to bring cases to the court. But this changed in 1998. The court's job is to make sure countries keep their promises. These promises are about respecting human rights as written in the ECHR.

The Court and the Council of Europe

The European Court of Human Rights is the most famous part of the Council of Europe. The Council of Europe (CoE) is an international group. It was started after World War II. Its goal is to protect human rights, democracy, and the rule of law in Europe.

The CoE began in 1949. It now has 46 member countries. About 700 million people live in these countries. The CoE has a budget of about 500 million euros each year.

The Council of Europe is different from the European Union (EU). The EU has 27 countries. People sometimes confuse them. This is partly because the EU uses the same flag of Europe and anthem of Europe that the Council of Europe created. No country has joined the EU without first being a member of the Council of Europe. The Council of Europe is also an official observer at the United Nations General Assembly.

Member Countries

All 46 member states of the Council of Europe accept the court's authority. On November 1, 1998, the court became a full-time court. A group called the European Commission of Human Rights, which used to decide if cases could be heard, was removed.

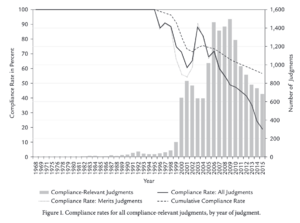

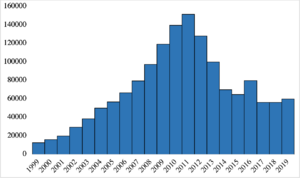

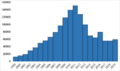

After the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, many new countries joined the ECHR. This led to a huge increase in cases sent to the court. The court's ability to work well was seriously threatened. There were too many cases waiting.

- In 1999, 8,400 cases were ready to be heard.

- By 2003, 27,200 new cases were filed. The number of waiting cases grew to about 65,000.

- In 2005, the court opened 45,500 new case files.

- By 2009, 57,200 cases were sent in. There were 119,300 cases waiting.

At that time, more than 90% of cases were not accepted. Most of the cases that were decided (about 60%) were "repetitive cases." This means the court had already made a decision on a similar issue.

To help with the large number of cases, a new rule called Protocol 11 was made. It made the court and its judges work full-time. It also made the process simpler and faster. But the number of cases kept growing. So, in 2004, countries agreed on more changes. They created Protocol 14. This new rule aimed to reduce the court's workload. It also helped the Council of Europe's Committee of Ministers. This group checks if countries follow the court's decisions. The goal was for the court to focus on important human rights issues.

Judges

Judges are chosen for a nine-year term. They cannot be chosen again. The number of full-time judges is the same as the number of countries that signed the ECHR. Currently, there are 46 judges. The ECHR says that judges must be "high moral character." They must also have the right skills for a high court job. Or they must be expert lawyers.

Each judge is chosen by a vote in the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. Each country suggests three people for the job. Judges are chosen when a judge's term ends. They are also chosen when a new country joins the ECHR. Judges usually retire at age 70. But they can keep working until a new judge is chosen. They can also finish cases they are already working on.

Judges work independently. They are not allowed to have ties to the country they were chosen from. This helps make sure the court is fair. Judges cannot be involved in anything that might affect the court's independence. They also cannot hear a case if they have a family or work connection to someone in the case. A judge can only be removed if two-thirds of the other judges agree. They must decide the judge no longer meets the requirements. Judges have special protections while they are working.

The European Court of Human Rights has help from a team of about 640 people. Almost half of them are lawyers. They are divided into 31 groups. This team helps the judges prepare for cases. They also communicate with people who bring cases, the public, and the news. The main clerk (Registrar) and their helper are chosen by all the judges.

Court Leadership and Management

All the court's judges meet together as the "plenary court." This group does not hear cases. Instead, it chooses the court's president, vice-presidents, and clerks. It also handles how the court is run. This includes rules, how judges work, and any changes needed.

The president of the court, the two vice-presidents, and three other section presidents are chosen by all the judges. These leaders serve for three years and can be chosen again. They are known for being fair and skilled. They must be independent. They cannot hold other jobs that might cause a conflict. Their home country cannot remove them. Only two-thirds of the other judges can remove them, and only for serious reasons.

The current president of the court is Robert Spano from Iceland. The two vice-presidents are Jon Fridrik Kjølbro from Denmark and Ksenija Turkovic from Croatia.

Court's Authority

The court has authority over the member states of the Council of Europe. This includes almost every country in Europe. Only Vatican City, Belarus, and Russia are not included. The court handles different types of cases:

- Cases between countries.

- Cases brought by individuals against countries.

- Giving advice on how to understand the ECHR.

Most cases heard by the court are brought by individuals. A small group of three judges handles some cases. Larger groups of seven judges handle others. The most important cases are heard by a "Grand Chamber" of 17 judges.

Cases from Individuals

Any person, non-governmental group, or group of people can bring a case. They can say that a country has broken their rights under the European Convention on Human Rights. The court's official languages are English and French. But people can send in their cases in any official language of the member countries. The case must be written down and signed by the person or their lawyer.

Once a case is received, it goes to a special judge called a "Judge Rapporteur." This judge decides if the case can be heard. A case might not be accepted if:

- It doesn't fit the court's rules about what it can judge.

- It's too old.

- The person bringing the case isn't allowed to.

- The person hasn't tried to solve the problem in their own country's courts first.

- It was sent in too late (more than four months after the last decision in their country).

- The person wants to remain anonymous.

- It's too similar to a case already heard or being looked at by another international group.

If the Judge Rapporteur decides the case can go forward, it goes to a group of judges called a "chamber." This chamber will then ask the country involved to explain its side.

The chamber then discusses and decides if the case can be heard and if the country broke the rules. If a case involves big questions about the ECHR, or if it might change how the court usually decides cases, it can be sent to the Grand Chamber. This happens if everyone involved agrees. A group of five judges then decides if the Grand Chamber will take the case.

Cases Between Countries

Any country that signed the European Convention on Human Rights can sue another country for breaking the agreement. But this happens very rarely. As of 2021, the court has decided five such cases:

- Ireland v. United Kingdom (1978): About very bad treatment in Northern Ireland.

- Denmark v. Turkey (2000): About a Danish person held in Turkey.

- Cyprus v. Turkey (IV) (2001): About missing people, the right of Greeks to return home, and the rights of Greeks living in the north. A later decision in 2014 awarded €90 million.

- Georgia v. Russian Federation (I) (2014): About Georgians being forced to leave Russia.

- Georgia v. Russian Federation (II) (2021).

Advisory Opinions

A group called the Committee of Ministers can ask the court for advice. This advice is about how to understand the European Convention on Human Rights. But they cannot ask about basic rights the court has already looked at.

How Decisions Affect Everyone

The ECtHR's decisions can affect all member countries. This is because the court makes decisions that are important for everyone. They help spread human rights ideas across all countries that signed the ECHR. However, not all countries agree that these decisions are legally binding on them all.

Court Process and Decisions

After deciding a case can be heard, the court listens to both sides. The court can investigate facts or issues in the case as it needs to. Countries must help the court with any information it asks for.

The European Convention on Human Rights says that most hearings should be open to the public. But sometimes, for special reasons, they can be private. In reality, most cases are handled privately through written documents. In private talks, the court can help both sides reach an agreement. If they do, the court checks if the agreement follows the ECHR. However, many cases do not have a hearing at all.

A decision by the Grand Chamber is final. Decisions made by a smaller chamber become final three months after they are announced. This is unless someone asks the Grand Chamber to review the case. If the Grand Chamber refuses to review it, the chamber's decision becomes final. The Grand Chamber has 17 judges. These include the court's president, vice-presidents, section presidents, and the judge from the country involved. Other judges are chosen by drawing lots. Grand Chamber hearings are open to the public. They are also streamed online. After the public hearing, the judges discuss the case.

The court's chamber decides if a case can be heard and if the country broke the rules. Usually, these two decisions are made at the same time. In its final decisions, the court states if a country has broken the ECHR. It can also order the country to pay money for harm caused. This can include money for emotional distress and legal costs.

The court's decisions are public. They must explain why the decision was made. Article 46 of the ECHR says that countries must follow the court's final decisions. However, advisory opinions are not legally binding. The court has always said it cannot cancel a country's laws or actions. It can only say if they break the ECHR.

The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe checks if countries follow the court's decisions. This group makes sure countries change their laws to match the ECHR. They also check if countries take steps to fix problems. Countries usually follow the court's decisions.

Chambers make decisions by a majority vote. Any judge who heard the case can write a separate opinion. This opinion can agree or disagree with the court's decision. If there is a tie in voting, the president makes the final decision.

Trying National Courts First

Article 35 of the European Convention on Human Rights says something important. Before you can go to the European Court of Human Rights, you must try to solve your problem in your own country's courts first. This rule exists because the European court is a "backup" court. It checks if human rights are being protected. You must show that your country's courts could not fix the problems. You need to use the right legal steps in your country. You also need to clearly say that your rights under the ECHR were broken.

Fair Compensation

The court can award money for damages. This is called "just satisfaction." This money can be for financial losses or for emotional harm. The amounts are usually small compared to what national courts might award. They rarely go over £1,000 plus legal costs. The amount for emotional harm often depends on what the country can afford to pay. It is not always based on how much the person suffered. Sometimes, if a country repeatedly breaks human rights, the awards might be higher to punish them. But sometimes, they might be lower, or the cases might even be dropped.

How the Court Works with Other Courts

European Court of Justice

The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) is not directly connected to the European Court of Human Rights. These two courts belong to different organizations. However, all countries in the EU are also members of the Council of Europe. This means they have all signed the ECHR. So, there are concerns about making sure the decisions of both courts are consistent. The CJEU often looks at the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights. It treats the ECHR as if it were part of the EU's own legal system. This is because the ECHR is part of the legal rules of EU countries.

Even though its member countries are part of the ECHR, the European Union itself is not. It didn't have the power to join under older treaties. But EU organizations must follow human rights rules under the ECHR. Since December 1, 2009, the EU is expected to sign the ECHR. This would mean the Court of Justice would have to follow the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights. This would help avoid conflicts between the two courts' decisions. However, in December 2014, the CJEU decided not to join the ECHR.

National Courts

Most countries that signed the European Convention on Human Rights have made the ECHR part of their own laws. They did this through their constitution, laws, or court decisions. The ECtHR increasingly sees talking with national courts as very important. This is especially true for making sure decisions are followed. A study from 2012 found that the ECtHR often uses its own past decisions to explain its rulings. This helps convince national courts to accept its decisions.

In 2015, Russia passed a law saying it could ignore ECtHR decisions. This law put into writing an earlier Russian court decision. That decision said Russia could refuse to accept an ECtHR decision if it went against the Constitution of Russia. In 2020, Russia made changes to its constitution. These changes said the Russian Constitution is more important than international law. (In March 2022, Russia was removed from the Council of Europe. This was because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its history of not following the ECHR's rules.)

Other countries have also tried to limit how binding ECtHR decisions are. They say it depends on their own country's constitution. In 2004, Germany's highest court ruled that ECtHR decisions are not always binding on German courts. Italy's highest court also limits how much ECtHR decisions apply.

A 2016 book described countries' attitudes towards ECtHR decisions:

- Mostly friendly: Austria, Belgium, Czechia, Germany, Italy, Poland, and Sweden.

- Moderately critical: France, Hungary, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, and Turkey.

- Strongly critical: The United Kingdom.

- Openly against: Russia.

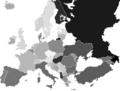

In 2019, a review said that countries in the South Caucasus followed the rules only partly.

How Well the Court Works

Many international law experts believe the ECtHR is the most effective human rights court in the world. Michael Goldhaber, in his book A People's History of the European Court of Human Rights, says scholars always use very positive words to describe it.

Following Decisions

The court cannot force countries to follow its decisions. Some countries have ignored ECtHR decisions. They have continued actions that the court said violated human rights. Countries must pay any money ordered by the court within a certain time (usually three months). If not, they will owe more money. But there is no strict deadline for more complex changes needed by a decision. However, if a country delays following a decision for a long time, it raises questions. It makes people wonder if the country truly cares about fixing human rights problems quickly.

The number of decisions not followed grew from 2,624 in 2001 to 9,944 by the end of 2016. Almost half of these (48%) had not been followed for five years or more. In 2016, almost all 47 member countries had not followed at least one ECtHR decision on time. But most of these unfulfilled decisions were from a few countries: Italy (2,219), Russia (1,540), Turkey (1,342), and Ukraine (1,172). More than 3,200 unfulfilled decisions were about police actions and bad prison conditions.

The Council of Europe's Commissioner for Human Rights, Nils Muižnieks, said: "Our work is based on cooperation and good faith. When you don't have that, it's very difficult to have an impact. We kind of lack the tools to help countries that don't want to be helped." Russia often ignores ECtHR decisions. It usually pays the money ordered but refuses to fix the underlying problem. This leads to many similar cases coming up again. Russian law has even set up a special fund to pay people who win cases at the ECtHR.

Some important decisions that were not fully followed include:

- In Hirst v. United Kingdom (2005), the court said that stopping all prisoners from voting broke the right to vote. A small change was made in 2017.

- The Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina was found to be unfair in 2009. It stopped citizens who were not Bosniak, Croat, or Serb from being elected to certain jobs. As of December 2019, these unfair rules have not been changed. This is despite three later cases confirming they go against the ECHR.

- In Alekseyev v. Russia (2010), the ban on Moscow Pride events was found to break freedom of assembly. In 2012, Russian courts banned the event for the next 100 years. The ECtHR confirmed its ruling in 2018.

- Bayev and Others v. Russia (2017), about the Russian gay propaganda law. The court said it limited freedom of speech.

- Azerbaijani politician Ilgar Mammadov was jailed. The ECtHR said his imprisonment was illegal in 2014. He was still in jail in 2017.

- After Burmych and Others v. Ukraine (2017), the ECtHR closed 12,143 cases. These cases were like Ivanov v. Ukraine (2009). They were all about people not being paid money they were owed by Ukrainian law. The court gave these cases to the Council of Europe to handle. Ukraine did not try to solve these cases for eight years. This led the ECtHR to "effectively give up" trying to make Ukraine follow its decisions. As of 2020, the money owed to these people is still unpaid.

Another problem is when countries delay following decisions.

Number of Cases

The number of cases sent to the court grew quickly after the Soviet Union broke up. It went from fewer than 8,400 cases in 1999 to 57,000 in 2009. Most of these cases came from countries that used to be part of the Eastern Bloc. People there often trust their own court systems less. In 2009, the court had 120,000 cases waiting. It would have taken 46 years to process them at the old speed. This led to changes. The BBC said the court "began to be seen as a victim of its own success."

Between 2007 and 2017, the number of cases handled each year stayed about the same (between 1,280 and 1,550). Two-thirds of cases were repetitive. Most concerned a few countries: Turkey (2,401), Russia (2,110), Romania (1,341), and Poland (1,272). Repetitive cases show that a country has a pattern of human rights problems.

The 2010 Interlaken Declaration said the court would reduce its workload. It would do this by dealing with fewer repetitive cases.

Because of the Protocol 14 changes, single judges could reject cases that were not allowed. A system of "pilot judgements" was also created. This helped handle repetitive cases without a full decision for each one. The number of waiting cases reached its highest point in 2011 (151,600). By 2019, it was down to 59,800.

These changes meant more cases were rejected or handled without a full ruling. According to Steven Greer, "many cases will not, in practice, be looked at." This situation is called a "structural denial of justice." It means some people with good cases might not get them heard. It can also be harder to get justice if people don't have legal help.

Impact of the Court

ECtHR decisions have made human rights stronger in every country that signed the ECHR. Some important rights that have been protected include:

- Article 2: The right to life. This includes ending the death penalty. It also means deaths in custody or from domestic violence must be properly investigated.

- Article 3: Freedom from torture and very bad treatment. This has helped stop police brutality and extremely poor prison conditions.

- Article 4: Cases under this article have led to laws against forced labor and human trafficking in several countries.

- Article 5: The right to liberty and safety. This has helped end very long pretrial detention. This is when innocent people are jailed for years before a trial.

- Article 6: The right to a fair trial. This includes overturning wrongful convictions. It also limits how long court cases can take to avoid unfair delays. And it helps make sure judges are fair.

- Article 8:

* The Right to privacy. This has included limits on wiretapping. It also led to making homosexuality legal in some places. * The Right to family life. This has helped end child custody rules that were unfair to men, LGBT people, and religious minorities.

- Article 9: Freedom of conscience and religion. This includes the right to refuse military service for moral reasons. It also protects the right to spread religious beliefs. It stops unfair burdens on practicing religion. And it prevents governments from interfering with religious groups.

- Article 10: Freedom of expression. This includes overturning defamation laws that stopped people from sharing opinions. It also protects whistleblowers and journalists who expose corruption or criticize the government.

- Article 11: Freedom of association and peaceful assembly. This includes the right to organize pride parades and political protests.

- Article 14 and Protocol 12: The right to equal treatment. This includes ruling against institutional racism affecting Romani people.

- Protocol 1, Article 1: property rights. This includes getting back property illegally taken by the state. It also ensures fair payment for property taken by the government for public use.

Awards and Recognition

In 2010, the court received the Freedom Medal from the Roosevelt Institute. In 2020, the Greek government suggested the court for the Nobel Peace Prize.

See also

In Spanish: Tribunal Europeo de Derechos Humanos para niños

In Spanish: Tribunal Europeo de Derechos Humanos para niños

- Strasbourg Observers

- African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights – a similar court started in 2006

- Human rights in Europe

- Inter-American Court of Human Rights – a similar court started in 1979

- List of LGBT-related cases before international courts and quasi-judicial bodies

- Category:European Court of Human Rights case law

Images for kids

-

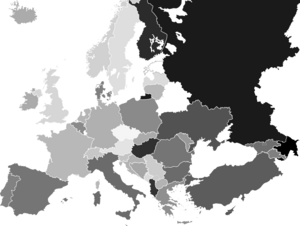

How well countries followed important ECtHR decisions from the last 10 years as of August 2021. Black means no follow-up, white means 100% follow-up. The average was 53%. Azerbaijan (4%) and Russia (10%) were lowest. Luxembourg, Monaco, and Estonia (100%) and Czechia (96%) were highest. (Belarus is white because it's not a member and doesn't follow rulings.)

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |