Plan of Campaign facts for kids

The Plan of Campaign was a special plan used in Ireland between 1886 and 1891. It was created by Irish political leaders to help tenant farmers. These farmers were struggling against landowners, especially those who lived far away or charged very high rents.

The plan started because farmers were having a tough time. Prices for milk and cattle had dropped since the 1870s. This made it hard for many tenants to pay their rent. Bad weather in 1885 and 1886 also ruined crops. This made paying rent even harder. Conflicts over land, known as the Land War, were starting again. More and more farmers were being evicted from their homes.

Contents

A Bold New Plan for Farmers

The Plan of Campaign was thought up by Timothy Healy. It was put together by Timothy Harrington, William O'Brien, and John Dillon. Harrington wrote about the plan in an article called Plan of Campaign. It was published on October 23, 1886, in the United Irishman newspaper. O'Brien was the editor of this newspaper.

The main goal of the Plan was to get landlords to lower rents. This was for tenants who felt they were paying too much. If a landlord refused to lower the rent, the tenants would pay no rent at all. Instead, campaigners would collect the reduced rent money. This money was then put into a special fund. This fund was used to help tenants who were evicted. The idea was to help them get their farms back quickly with fair rents.

A special group called the Land Commission had already been set up in 1881. Its job was to check and lower rents that were too high. It had already lowered rents by about 25%. The Plan of Campaign wanted to lower rents even more. It aimed to do this through group action and talking with landlords.

The Plan was meant to be used on 203 estates across Ireland. Many landlords agreed to the lower rents at first. Some held out but then agreed. Tenants on a few estates gave up. The biggest problems happened on the remaining large estates. The Plan's leaders decided to focus on a few of these. They hoped this would make other landlords give in.

A lot of attention went to the Clanricarde estate in Portumna, County Galway. John Dillon and William O'Brien started the Plan there on November 19, 1886. The landlord, the Marquess of Clanricarde, lived far away. His estate was huge, about 52,000 acres (21,000 hectares). It brought in £25,000 a year from 1,900 tenants. The struggling tenants asked for a 25% rent cut. The landlord said no. So, the tenants put their reduced rent money into a special fund. They told the landlord he would only get it if he agreed to the cut. About 20,000 tenants joined the Plan across different estates. Each estate's plan was led by a member of the Irish Parliamentary Party.

Parnell's Difficult Choice

Charles Stewart Parnell was the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. He was focused on getting British voters to support Irish Home Rule. This meant Ireland would have its own government. In the 1885 election, Parnell's party held the balance of power in the British Parliament. He supported the Conservative government at first.

Then, William Ewart Gladstone, leader of the Liberal Party, promised to bring in Home Rule. Parnell then switched his support to the Liberals. Gladstone formed a new government and introduced the First Irish Home Rule Bill in April 1886. But many people, especially Unionists and Conservatives, opposed it. Gladstone's own party even split. The Bill was defeated in June 1886. The next election gave a majority to the Conservatives and their allies. This showed how much people feared Home Rule.

Parnell was still determined to get Home Rule. But he kept his distance from the Plan of Campaign. He did not want Home Rule to be linked with violent actions over land. His supporters wanted to gain votes from ordinary people. They also wanted to stop support for more radical leaders like Michael Davitt. They were using Davitt's methods but with less extreme goals.

In December 1886, the Conservative government said the Campaign was "unlawful." Parnell asked O'Brien to limit the Plan to the estates where it was already active. However, the Plan had strong support from Catholic leaders. This included Archbishop William Walsh of Dublin and Archbishop Thomas William Croke of Cashel. Many other bishops supported it too. But the Bishop of Limerick, Edward O'Dwyer, was against it. The Church itself faced problems. It had lent money to some Catholic landlords. These landlords could not pay back their loans if they weren't getting rents.

The Coercion Act and Its Impact

The return of land conflicts worried the government. To stop the Plan, Prime Minister Salisbury appointed his nephew, Arthur Balfour, as Chief Secretary of Ireland. Balfour quickly passed a strict law called the Irish Coercion Act (1887). This law aimed to stop boycotting, threats, illegal meetings, and plots against paying rents.

The Act led to hundreds of people being jailed. This included over twenty Members of Parliament. They were jailed just for helping evicted tenants. The Catholic Church leaders spoke out against this "Crimes Act." It became a permanent law and did not need to be renewed each year. Trials by jury were also stopped. Balfour also made the National League illegal and closed its local groups.

He sent armed police and soldiers to evict tenants. They even used battering rams against small homes. These dramatic scenes were shown in newspapers worldwide. They created a lot of sympathy for the evicted tenants in Britain.

John Dillon and William O'Brien were arrested. When their supporters started a fund to help them, Archbishop Croke issued a "No Tax Manifesto." Balfour even thought about jailing him. Two priests, Fr. Matt Ryan and Fr. Daniel Keller, were imprisoned. In 1887, O'Brien and a farmer named John Mandeville were on trial in Mitchelstown. Dillon was there and gave a speech against Balfour. A crowd of 8,000 people threw stones at the police. The police then fired, killing three people. This event became known as the "Mitchelstown Massacre." Balfour defended his officers. O'Brien then called him "Bloody Balfour" in Parliament.

A special investigation, the Parnell Commission, happened in 1888–89. It cleared Parnell of involvement in murders. But it also showed that there was a lot of violence and threats during the Land War and the Campaign. The government felt this justified their strict new laws.

The Pope's Message

The rising crime and unrest made Balfour try new tactics. He asked the Vatican for help to stop priests from being involved in the Plan. In response, Pope Leo XIII sent Archbishop Persico to Ireland. He traveled around the country from July 1887 to January 1888. He spoke with important church leaders.

On April 20, 1888, the Pope issued a special message. It said the Plan of Campaign and all church involvement in it were wrong. It also condemned boycotting. In June, a Papal encyclical (a letter from the Pope) called "Saepe Nos" was sent to all Irish bishops.

Irish politicians and even some clergy openly disagreed with this. Many people resented the Vatican getting involved in Irish matters. This actually helped gain some support for the Plan, which was having money problems. Some suspected the Pope's message was sent to help Britain and the Vatican become closer.

The Pope's letter said that tenants could not just decide to lower their rent. It said there were special courts to handle such disagreements. It also said that boycotting was wrong. It was unfair to treat people badly just because they paid their agreed rents or took vacant land.

Archbishop Persico was surprised by the Pope's direct condemnation. He had expected the Irish bishops to make the statement, not the Pope directly. Persico returned to Rome disappointed.

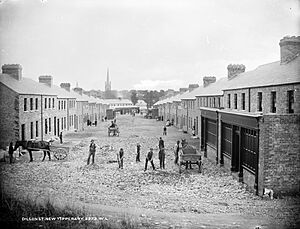

Building New Tipperary

In 1889, Balfour encouraged landlords to form a group against the tenants. This group was led by Arthur Smith-Barry. He was a landlord from Tipperary. Smith-Barry was allowed to buy estates threatened by the Plan. Then he would evict the tenants. He did this on an estate in Youghal.

This led to a conflict with his own tenants in Tipperary town. In anger, they refused to pay rents. When they were evicted, they moved their shops and homes outside the town. They built 'New' Tipperary under the guidance of Fr. David Humphreys and O'Brien. This new town had two streets of houses. But the project was too expensive for the Plan's leaders. This helped lead to the Plan's defeat.

Parnell eventually gave some support. This helped form a Tenants' Defence Association in Tipperary. With money raised by Dillon, the Plan continued. In 1890, the organizers had £84,000. But this dropped to £48,000 within a year. By then, almost 1,500 tenants were getting money from the Plan's funds.

Parnell Changes His Stance

The Plan's organizers looked to Parnell for more help, but he didn't provide it. In May 1888, Parnell gave a speech where he seemed to distance himself from the Plan. He was worried it would hurt his alliance with the Liberal Party. This disagreement within his party was a sign of bigger problems to come.

The organizers had to find money elsewhere. Dillon went on a fundraising trip to Australia and New Zealand from May 1889 to April 1890. He raised about £33,000, but it wasn't enough. In October, Dillon and O'Brien left the country to avoid arrest. They went to France and then to America. Parnell gave them permission to raise more money there. They raised £61,000, which Parnell wanted for the Irish party.

Parnell also had to distance himself from the Campaign during the Parnell Commission hearings in 1888–89. While the main result was good for him, much of the evidence suggested that the Campaign's organizers had encouraged violence.

The End of the Campaign

As Balfour had hoped, the organizers found it hard to raise enough money. They needed to pay those who had been evicted during the Campaign. By 1893, the Campaign was over. It had led to agreements on eighty-four estates. On fifteen estates, the tenants had given in to the landlords' terms. No agreement was reached on the remaining estates.

The organizers said they had won. But the cost was high. There was a huge amount of money spent. People suffered greatly in prison under the Coercion Acts. Many evicted farmers lost their homes and their farms were neglected. Some didn't get their farms back until 1907. The relationships between landlords and tenants became very bitter.

The Campaign brought many British and foreign journalists to Ireland. Some Liberal Members of Parliament also came and were even jailed under the Coercion Acts. This increased sympathy for Home Rule. The Conservative Party lost support among working-class people in Britain because of how they handled the situation.

However, a decade later, Balfour passed several laws to help Ireland. He changed and introduced new land acts. He supported economic plans, local businesses, and extending railways. He also brought in local government. Balfour's approach was to be tough on lawbreakers but also to fix problems, especially regarding land.

Lasting Changes

In December 1890, the Irish Parliamentary Party split. This happened after a divorce case involving Parnell. This split took attention away from the Campaign, which slowly faded out. The party also wanted to avoid the more violent parts of the Campaign. This was important as they approached the Second Home Rule Bill. This Bill passed in the House of Commons but was defeated by the House of Lords in 1893.

The issue of land in Ireland was finally addressed after the 1902 Land Conference. The most important reform was the Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903. This act was passed during Balfour's time as Prime Minister (1902–05). It allowed Irish tenant farmers to buy their land. They could do this with low yearly payments and affordable government-backed loans.

|

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |