Michael Davitt facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Michael Davitt

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 25 March 1846 Straide, County Mayo, Ireland

|

| Died | 30 May 1906 (aged 60) Elphis Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

|

| Nationality | Irish |

| Occupation | Writer, lecturer, and journalist |

| Known for | Irish Land League activism |

| Political party | Irish Parliamentary Party Irish National Federation |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Yore (m. 1886) |

| Children | 5, including Robert and Cahir |

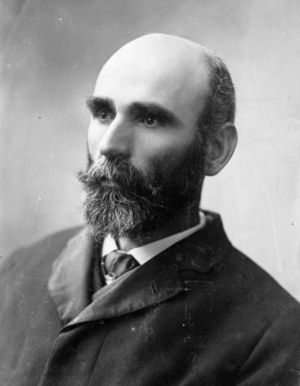

Michael Davitt (born March 25, 1846 – died May 30, 1906) was an important Irish activist. He worked for many causes, especially for Ireland to govern itself (called Home Rule) and for changes to how land was owned.

When he was four years old, his family was forced to leave their home. They moved to England. Michael Davitt later became a leader in the Irish Republican Brotherhood. This group wanted to end British rule in Ireland and sometimes used force. In 1870, he was found guilty of a serious crime related to weapons and spent seven years in prison.

After he was released, Davitt helped create a new plan. This plan brought together different groups of Irish nationalists to work on land reform. In 1879, he helped start the Irish National Land League with Charles Stewart Parnell. This was when he had the most influence, before he was sent to prison again in 1881.

Davitt traveled a lot, giving talks around the world. He also earned money by writing for newspapers. In the 1890s, he became a Member of Parliament (MP) for the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP). When the party split due to Parnell's personal issues, Davitt joined the group that opposed Parnell. He believed that land should belong to the people, which put him on the left side of Irish nationalism. He strongly supported an alliance between the Liberal Party and the IPP.

Contents

Michael Davitt's Early Life

Michael Davitt was born in Straide, County Mayo, Ireland, on March 25, 1846. This was during the terrible Great Famine. He was the third of five children. His parents, Martin and Catherine Davitt, were poor tenant farmers. They spoke Irish at home.

In 1850, when Michael was four, his family was evicted from their home. They couldn't pay their rent. Davitt later said that this event, which he remembered, caused many problems for his family. Like many Irish people then, his family decided to move to England. They sailed to Liverpool and then walked to Haslingden, in East Lancashire, where they settled.

His parents worked hard, selling fruit and doing other odd jobs. Martin, who could read and speak English, even ran a night school in their home. They shared their home with other Irish families. The Davitt family faced prejudice from English workers. These workers thought Irish immigrants lowered wages.

Davitt started working at age nine in a cotton mill. Two years later, his right arm got caught in a machine. It was so badly hurt that it had to be removed. He did not receive any money for his injury, which was common back then.

After his accident, a kind person named John Dean helped him. Dean sent Davitt to a school. In August 1861, at 15, he got a job at a post office. The owner also ran a printing business. Davitt joined the Mechanics' Institute. He kept reading and studying, and went to many lectures. He learned about the Chartist movement. Davitt later said that a Chartist leader was the first Englishman he heard speak against unfair land ownership in Ireland.

Davitt was on his way to a better life as a working-class person. But in 1865, he chose a different path. He joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).

Joining the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The IRB was a secret group. It believed in using force to end British rule in Ireland. Many young Irish immigrants joined it. Davitt quickly became a leader of the local IRB group in Rossendale. In February 1867, Davitt led about fifty members in a failed attempt to get weapons from Chester Castle. This was for the planned Fenian Rising later that year. He found out the police knew their plan and managed to get his men away without being caught.

In 1868, he left his printing job to work full-time for the IRB. He was an organizer and bought weapons for them in England and Scotland. He pretended to be a traveling salesman to hide his real work.

Authorities wanted Davitt since 1867, but they didn't know how important he was to the IRB. In 1869, police found a letter Davitt wrote. It seemed to approve of a murder. After a lot of police work, Davitt was arrested at Paddington Station in London on May 14, 1870. He was waiting for a delivery of weapons. In July, he was found guilty of a serious crime for helping an uprising. He was sentenced to fifteen years in prison. He felt he didn't get a fair trial.

Davitt was held in different prisons. He spent months alone and had to do hard labor. The poor food and conditions hurt his health permanently. He often broke prison rules. He felt he should be treated differently from other criminals because he was a political prisoner. In 1872, he secretly sent a letter out of prison. It was published in newspapers and led to an investigation into his claims.

Davitt was released on December 19, 1877. He had served seven and a half years. This happened after groups like the Home Rule League pushed for all Irish political prisoners to be freed.

He and other freed prisoners were welcomed as heroes in Ireland. Davitt wrote a book about his time in prison. He started a campaign to free other Irish prisoners. He found he was good at writing and giving talks. He also rejoined the IRB. But the success of freeing prisoners made him see the value of political action. He realized it could work better than just using force to achieve Irish goals. His prison experiences made him want better conditions for all prisoners, not just political ones.

Before his arrest, Davitt had convinced his family to move to the United States. In July 1878, Davitt visited them. He also gave talks to raise money to bring his mother and youngest sister back to Ireland. (His father had passed away). In New York, he was welcomed by an Irish-American group called Clan na Gael.

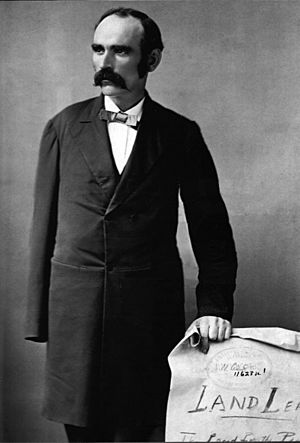

During meetings with Irish-Americans, Davitt developed a new plan. It was called the "New Departure." This plan was an informal way for groups who used force and groups who worked through Parliament to cooperate. They would focus on changing land laws. This cooperation became stronger in June 1879. Davitt, John Devoy (from Clan na Gael), and Charles Stewart Parnell (leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party) met in Dublin. Parnell's party wanted Home Rule through Parliament.

The Land War: Fighting for Fair Land Rights

In 1879, bad weather, poor harvests, and low prices caused hunger in western Ireland. This led to unrest among farmers. Davitt helped organize large meetings in Mayo to demand land reform. At one meeting, he called for Ireland to be free from "land robbers."

On August 16, 1879, the Land League of Mayo was started. On October 21, it was replaced by the Irish National Land League in Dublin. Parnell became its president, and Davitt was one of its secretaries. From 1879 to 1881, Davitt had the most political power through the Land League.

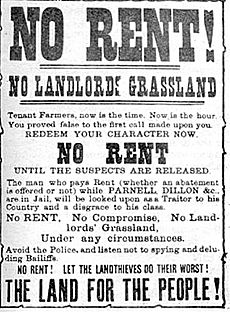

The Land League used the slogan "the land for the people." This idea was popular with all Irish nationalists. The British government worried about how popular the Land League was among Irish Catholics. However, Davitt's work with Parnell angered the IRB. They removed Davitt from their main council in May 1880, though he remained a member of the group.

One famous action of the Land League was against Captain Charles Boycott. He was a land agent. In the autumn of 1880, people refused to work for him or have anything to do with him. This led to Boycott leaving Ireland in December. This type of protest became known as a "boycott."

In May 1880, Davitt traveled to the United States. He wanted to raise money for the Land League. He specifically wanted to help Irish farmers avoid being beggars. He attended the first meeting of the American Land League. There, he was made secretary. As secretary, Davitt helped improve the Land League's organization. He set up local branches. For thirteen weeks, Davitt and Lawrence Walsh were the main national leaders. They worked closely with Anna Parnell, Charles Parnell's sister. While in the United States, Davitt gave speeches across the country.

The British government responded to the land protests with a new law in 1881. This law allowed them to arrest people involved in the Land War without a trial. Irish MPs strongly protested this law but could not stop it. It was Davitt's idea to create a Ladies' Land League. This group would continue the work if the male leaders were arrested.

On February 3, 1881, Davitt was arrested in Dublin and sent back to prison. Many Irish MPs protested in Parliament, and thirty-six were expelled. Almost a thousand people were arrested under the new law. But crimes related to land continued to increase. In April, the government introduced another law. This law aimed to fix many of the farmers' problems. It granted "fair rent, free sale, and fixity of tenure." This meant fairer prices for rent, the right to sell improvements on their land, and more secure leases. The Land League criticized it for not giving land ownership to peasants. However, Davitt later said it "struck a mortal blow at Irish landlordism."

Davitt spent most of his second prison term in better conditions. This was because he was famous and people worried about his health. He was allowed books and continued to study ideas about land. He became interested in the ideas of Henry George. He then changed his mind about peasant ownership. Instead, he supported the idea of the government owning all land. He also read many liberal thinkers.

In October 1881, Parnell and other IPP leaders were also arrested. The Land League responded by telling tenant farmers not to pay rent. Two days later, the British government banned the Land League. Davitt and his friends were released from prison in May 1882. This happened because of an agreement between the IPP and the government. Many tenants who owed rent were forgiven. In return, the IPP stopped supporting land protests and ended the "No Rent Manifesto." This brought an end to the Land League.

Travels and Marriage

In June and July 1882, Davitt traveled to the United States to give talks. When he returned, he toured Britain with Henry George. They campaigned for the government to own land. They also pushed for an alliance between British workers, Irish laborers, and tenant farmers. This idea was not popular in Ireland. The IPP, which represented Irish tenant farmers, strongly opposed it.

After meeting with Parnell in September 1882, Davitt agreed to stop pushing for land nationalization. He decided to work with the IPP again. He helped start a new group called the Irish National League. This group included some of Davitt's ideas, but it focused more on Home Rule. Parnell also agreed to support a new group to help rural laborers get land and the right to vote.

After the Land League ended, some extreme groups continued to use force. Davitt spoke out against both these bombings and the British government's harsh actions. In February 1883, he was arrested for speaking out against the government. He spent four months in jail, which was his last time in prison.

Davitt often visited Scotland. He became involved in the struggles of farmers there. He encouraged Irish immigrants to get involved in the politics of their new country, especially the growing Labour movement. Davitt also worked with Welsh activists in 1886 to campaign for land reforms.

Davitt married Mary Yore, an Irish-American woman, on December 30, 1886, in Oakland, California. He had met her during his 1880 tour. They settled in a small house in Ballybrack, County Dublin. This was the only gift Davitt ever accepted from his supporters. They had five children. One daughter, Kathleen, died at age seven from tuberculosis in 1895. One son, Robert Davitt, became a national lawmaker. Another son, Cahir Davitt, became President of the High Court.

From 1880, Davitt earned money from journalism. He had always wanted to edit his own newspaper. In September 1890, he started a socialist weekly paper called Labour World. Davitt's paper covered many topics, like foreign news, the problems of farm workers, and women in the workplace. It was popular at first, but it stopped publishing the next year. This was due to Davitt's illness, lack of money, and other issues.

Davitt came to disagree with Parnell's leadership for several reasons. He felt Parnell had misled him about personal issues. He also believed that the cause of Ireland was more important than any one person. He worried that Parnell's personal problems would hurt the alliance between the IPP and the Liberal Party. When Parnell refused to step down, Davitt joined the group that opposed Parnell. He became one of Parnell's strongest critics. Later in his life, he balanced his criticism of Parnell with appreciation for his achievements.

Michael Davitt's Time in Parliament

Throughout the 1880s, Davitt had refused to become a Member of Parliament. He believed he could do more good as an activist outside of Parliament. He also felt that the IPP relied too much on parliamentary politics. He disliked Westminster, calling it a "parliamentary penitentiary." He knew that becoming an MP would upset his supporters abroad.

Davitt was elected for North Meath in the 1892 general election. But his election was overturned because he had been supported by the Catholic Church. He then ran unopposed for North East Cork in a special election in February 1893. He gave his first speech in Parliament in favor of the Home Rule Bill in April. This bill passed in the House of Commons but was defeated in the House of Lords in September. The Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone, who supported Home Rule, then retired. This delayed Home Rule for another twenty years. Davitt had spent a lot of his own money on his 1892 campaign. He had to declare bankruptcy in 1893 and resign from Parliament.

For seven months in 1895, Davitt toured Australia and New Zealand to earn money. This trip led to his second book, Life and Progress in Australasia (1896). In it, he paid special attention to how these countries were governed. He also wrote about the situation of minority groups, like Indigenous Australians and Pacific Islanders brought to work in poor conditions. Davitt noted that Western Australia, with a population of only 45,000, had its own Parliament. Meanwhile, Ireland, with five million people, was denied Home Rule. The seven colonies he visited had many Irish people who had supported the Land League. This gave Davitt an audience for his message. While abroad, he was elected for both South Mayo and East Kerry. He chose to represent Mayo, his birthplace.

Davitt supported the British Labour leader Keir Hardie. He also favored starting a Labour Party. But his commitment to the Liberal Party, for the sake of Home Rule, stopped him from joining the new party. This caused a disagreement with Hardie. In Parliament, Davitt pushed the government to improve conditions in western Ireland.

In 1898, Parliament passed a law that gave local control to County and District Councils in Ireland. This was a way to avoid Home Rule. Davitt then helped start the United Irish League with William O'Brien. This group wanted to give grazing land to small farmers. At the time, O'Brien was not popular because of his ideas about land. Davitt was one of the few experienced leaders willing to work with him.

Final Years and Passing

Davitt left Parliament for good on October 26, 1899. He did this to protest the Second Boer War. He spoke out against the war and the fact that Ireland had to pay a lot of money for it, even though most Irish people opposed it. He called it "the greatest infamy of the nineteenth century."

He then got jobs from American and Irish newspapers. He traveled to South Africa to report on the war and support the Boer side. On March 26, 1900, he arrived in Pretoria. He spent the next three months touring and visiting Irish soldiers fighting with the Boer army. Davitt was impressed that the Boers were a "small nation of courageous fighters" against the British Empire.

The groups that supported and opposed Parnell finally came together in 1900. The United Irish League grew very quickly. But it did not become the main Irish nationalist movement. To fight the League, the British government started arresting its leaders. By September 1902, forty League leaders were in jail. Davitt and John Dillon were in the United States raising money when a new land law was being discussed. By the time they returned, the Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903 was already decided. Davitt criticized this law. He felt it was too generous to landlords selling their lands to tenants. He believed the land rightfully belonged to the people.

Later, in 1906, Davitt supported the Liberal Party's idea for state control of schools. This was different from the Catholic Church's view of religious education. This led to a conflict between Davitt and the Catholic Church. This was the last major disagreement Davitt was involved in.

Michael Davitt passed away in Elpis Hospital, Dublin, on May 30, 1906, at age 60. He died from an infection after a tooth extraction. As he wished, his funeral was private. He was buried in Straide. However, many people still showed their respect. Businesses in Dublin closed, and many MPs and large crowds attended the procession. Many mourners followed the train carrying his body. A procession of almost one mile followed his coffin from the station to Straide.

Davitt's belongings were valued at £151. In his will, he wrote: "To all my friends I leave kind thoughts, to my enemies the fullest possible forgiveness and to Ireland the undying prayer for absolute freedom and independence, which it was my life's ambition to try and obtain for her."

Michael Davitt's Beliefs

Even though he was a member of the IPP, Davitt often had his own ideas. These ideas were sometimes different from his party's. Davitt was more radical than Parnell, which caused disagreements between them. Parnell saw land protests mainly as a way to make the IPP more popular and advance Home Rule. Davitt's main goal was to improve the lives of Irish farmers, especially the poorest ones. Parnell was a skilled politician, but Davitt was excellent at organizing and activism. For example, Davitt supported the Ladies' Land League even after Parnell spoke against it.

Davitt believed that having access to land for farming was a basic human right. He thought this right was more important than property rights. He felt that the landlord system was unfair and had been forced on Ireland by the British. His ideas were also greatly shaped by Henry George. Davitt came to believe that simply changing tenancy laws would not achieve "land for the people." He also thought that even if peasants owned small plots, these would eventually be combined into larger estates.

Instead, from 1882, Davitt argued that the government should buy all land. Owners would be paid for it. Then, the government could use the rent from this land for public projects that would benefit everyone.

Davitt's ideas about Irish independence were influenced by the Chartist movement. For example, his 1878 plan had three main points: the right to own weapons, self-government, and land reform. All these ideas were also supported by Chartism. Davitt argued that if Ireland had Home Rule, conditions would improve. This would reduce Irish people moving to Britain, which would mean less job competition for British workers.

Davitt was educated in a Methodist school. He accepted different religious beliefs. He did not want religious leaders to have too much influence in politics. He wanted Irish nationalism to include everyone, not just Catholics. Davitt's left-wing views made him a natural friend of the Liberal Party's radical group. He supported the alliance between those who wanted Home Rule and the Liberal Party. Unlike many other Irish nationalist leaders, Davitt supported women's suffrage, meaning women's right to vote.

According to a writer named T. W. Moody, Davitt strongly disliked the British Empire and unfair land ownership. But because he grew up in England, Davitt had positive views of English people. He also understood what was important to the working class in England.

Davitt's Views on Jewish People

In 1903, Davitt traveled to Kishinev, in the Russian Empire. He went there to investigate attacks on Jewish people for an American newspaper. He was one of the first foreign journalists to report on the Kishinev pogrom, which was a violent attack against Jewish communities. In his book, Within the Pale: The True Story of Anti-Semitic Persecutions in Russia (1903), Davitt supported Zionism. He believed that Jewish people needed their own independent homeland. He thought this was the only way to solve the "Jewish Question" (the challenges faced by Jewish people), just as it was for the "Irish Question."

In 1898, Davitt spoke out against certain financial figures. He opposed the 1904 Limerick boycott against the Jewish community in Limerick, Ireland. This boycott was organized by a priest. Davitt stated in a newspaper that Limerick citizens should "not allow the fair name of Catholic Ireland to be sullied through an anti-Jewish crusade."

While Davitt opposed violent attacks, some of his other statements about Jewish people were complex. He recognized that Jewish business activities were often because they were excluded from many other jobs. Davitt was seen as a hero by many Jewish people after his writings on Kishinev. Plays were even written about him. A historian named T. W. Moody believes that Davitt's "passion for social justice... transcended nationality."

See also

In Spanish: Michael Davitt para niños

In Spanish: Michael Davitt para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |