United Irish League facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

United Irish League

|

|

|---|---|

| Leader | William O'Brien (Jan 1898 – Dec 1900) John Redmond (Dec 1900 – Mar 1918) Joseph Devlin (Mar 1918–1920s) |

| Founder | William O'Brien |

| Founded | 23 January 1898 |

| Dissolved | 1920s |

| Ideology | Land reform Political reform Irish Home Rule |

| National affiliation | None (1898–1901) IPP (1901–1918) |

The United Irish League (UIL) was a political group in Ireland. It started on January 23, 1898, with the slogan "The Land for the People." Its main goal was to help small farmers get land. They wanted to make large farm owners give up their land. This land would then be shared among the smaller farmers. William O'Brien founded the UIL in Westport, County Mayo. Many important people and local Catholic priests supported it. By 1900, the UIL had grown to 462 local groups across 25 counties.

Contents

Background: Why the League Started

In 1895, William O'Brien left the British Parliament. He also left the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP). This party had split into many smaller groups. O'Brien was tired of the arguments within the party. He felt they were not helping the Irish people enough.

After leaving politics, O'Brien moved to western Ireland. There, he saw how hard life was for small farmers. They struggled to live on tiny plots of rocky land. Meanwhile, large farms called "grazier ranches" were owned by wealthy people. These owners included local shopkeepers and retired police officers. O'Brien called these people "grass-grabbers." Small farmers often had to rent land from them. O'Brien believed these large farms needed to be broken up. He wanted the land to be given to the small farmers. This was a new and bold idea at the time.

Earlier land protests in the 1880s had helped some farmers buy land. But by the 1890s, the problem of "grass-grabbers" was still there. O'Brien decided to start a new campaign. He wanted a law that would force large farm owners to sell their unused land. This land would then be given to small farmers. The government did not pass such a law. This made O'Brien believe that more than just talking in Parliament was needed. He felt strong action was required to help the people.

Objectives: What the League Wanted to Do

Ireland's population had dropped a lot since the Great Famine. Much farmland had been turned into large grazing areas. This meant many people lived on tiny plots of land. They could see large, empty fields nearby, but couldn't use them.

In January 1898, O'Brien started the United Irish League (UIL). He did this in Westport, the same place where the Irish Land League had started years before. The UIL's main goal was to break up large farms. They wanted to force owners to give their land to the Congested Districts Board for Ireland. This board would then share the land among small farmers. Many people, including some priests, liked this idea. The government, however, watched the new group closely. O'Brien's League brought new energy to the country.

Local priests in Westport and Newport strongly supported the League. One priest even called for a group "to hunt the grabbers and Scottish graziers out of the country." By September 1899, the League had grown. All six bishops in the Connacht region approved of its goals. They wanted to help small farmers get more land in western Ireland. The Church leaders generally agreed with the League's aims.

The League also aimed to bring together different political groups. It wanted them to work together on land issues and political changes. They also wanted to achieve Home Rule for Ireland. William O'Brien was the main person behind this. It was a difficult task because political leaders had different ideas. For example, John Dillon thought land issues were key to Home Rule. O'Brien wanted to help small farmers against large ones. Michael Davitt had once wanted the government to own all land. He was not very keen on farmers owning their own land.

O'Brien said his group had no political goals. But he knew that the split Irish Parliamentary Party needed to reunite. He believed that protests combined with political pressure were the best way to reach their goals. He did not believe in using violence. O'Brien and Davitt hoped that organizing people across the country would force the party to reunite. They wanted to elect "good men" to Parliament. Dillon was unsure about the new group. He thought it might cause problems with the government. He also worried it would harm their alliance with the Liberal Party in Britain. This caused the first big disagreement between O'Brien and Dillon.

Expansion: How the League Grew

John O'Donnell helped organize the UIL as its general secretary. The League did very well and became a threat to the divided Irish Parliamentary Party. It quickly gained support from farmers. Its local groups spread across most of Ireland. The UIL told the old party leaders how to reunite the party and the nationalist movement. The UIL also supported things like bringing back the Irish language and growing Irish industries.

O'Brien's new newspaper, The Irish People, supported the movement. It ran from September 1899 to November 1903. In it, O'Brien said the League belonged to the people, not politicians. The League had a detailed structure with a National Directory. The UIL's growth from the ground up made the divided members of the Irish Parliamentary Party reunite. They wanted to stop the UIL from becoming too powerful.

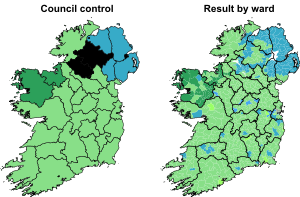

The League immediately focused on land redistribution. This was a goal the Irish Land League had worked on years before. But it had been forgotten after the Irish Parliamentary Party split. The UIL's first big goal was the county council elections. These were held under the new Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898. This law was a big change. It took power away from the wealthy landlords. For the first time, local people could vote for their own local councils. This gave them control over local matters. It was a huge step towards people's rights and rebuilding the economy.

The new councils had a big effect on Ireland. They let local people make decisions for themselves. These councils gave a platform to those who wanted Home Rule. They reduced the power of those who wanted to stay part of Britain. The new system also helped create a new group of politicians. Many of these experienced leaders would later play a role in Irish politics in the 1920s.

The first local elections under the new law were in spring 1899. The League's candidates won many seats. Nationalist councillors began to manage local affairs. Before, landlords had done this. In some areas, like county Cork, people supported trade unions and workers' groups. Here, the Irish Land and Labour Association (ILLA) was strong. D. D. Sheehan, a newspaper editor, helped the UIL and ILLA grow in Cork. He made sure their news was in his paper, The Southern Star. At first, the UIL and ILLA worked together. But later, their different goals led to problems and divisions.

The UIL's plan to help the poor against the rich appealed to many simple farmers. This was why the movement spread so quickly. By April 1900, the League had 462 local groups. It had between 60,000 and 80,000 members in 25 counties. Within two years, O'Brien's UIL was the largest group in Ireland. It had 1,150 local groups and 84,355 members.

Party Reunited

Around 1900, O'Brien was a very important person in the nationalist movement. He was a strong supporter of land reform. Although he wasn't officially the leader, he had a lot of influence. Michael Davitt had helped the League a lot. But in February, he left the country because he was sick. The question of who would lead the party now came down to O'Brien and John Redmond. O'Brien seemed to have the most power, but Redmond was already the leader of the Irish party. O'Brien was not a typical politician. He was good at connecting with people, but he didn't have a strong desire for power.

The UIL's fast growth led to the Irish Parliamentary Party reuniting. This happened on February 6 in London. They chose John Redmond MP as their leader. They were worried about O'Brien's growing power. The two main parts of the old party, the National League and the Irish National Federation, joined with the UIL. The UIL became the main support group for the Irish politicians in Parliament. Many of the UIL's organizers were from the old National League. O'Brien had brought them back to work for the new group. The UIL did well in areas where farmers really wanted land.

After the reunion, League organizers worked hard to spread the UIL across Ireland. The big increase in members in 1900 likely came from old National League and National Federation groups joining. The new group had a lot of energy that the older groups had lost. There was some tension between the League and many priests. The Church was very powerful in rural Ireland. This sometimes frustrated young, ambitious men from poorer backgrounds. Years before, such men might have joined secret protest groups. Now, they found a place in the United Irish League.

One big question remained: who would be the League's president? O'Brien was very popular. He had created the League mainly to push for land purchase through strong protests. He wanted to make sure the UIL stayed focused on this goal. He believed that people who were passionate about land protests should control the UIL. A big meeting of the League was held in Dublin on June 19 and 20, 1900. This meeting showed the League's success as a national organization. It had detailed rules and a constitution written by O'Brien. Redmond was chosen as chairman. Redmond planned to take control of O'Brien's organization. He wanted to make it serve the party's goals in Parliament. He became president in December. Within two years, Redmond and Dillon managed to bring the UIL under the Irish Parliamentary Party's control. They took it away from O'Brien.

In the September 1900 general election, O'Brien was re-elected to Parliament. He returned as the founder of the League and a key party leader. He was proud that the reunited party fought its first election based on the UIL's ideas. However, O'Brien was worried about the unity. Many ineffective politicians were re-elected. This stopped the UIL from choosing better candidates. The new leader, Redmond, now had to create a strong political group. By 1901, revolutionary nationalism was quiet, but it would soon become strong again.

Renewed Protests

In early 1901, protests were limited. Only 35 cases of boycotting were reported. This was because O'Brien was not well, and Davitt was in America. Despite this, the government outlawed League meetings. This was their usual reaction to any sign of public unrest.

By August 1901, the UIL had nearly 100,000 members. Its leaders called for active protests across Ireland. O'Brien, at the peak of his influence, controlled the UIL. In a strong speech on September 15, he called for "a great national strike against ranching and grabbing." He wanted people to boycott and fill Irish jails. Dillon also gave fiery speeches against the government. He encouraged farmers to demand lower rents and to "drive every landlord out of the country."

By January 1902, the League had 1,230 local groups. This set the stage for a conflict. The government was strong and did not want a land war in Ireland. The League was determined to fight landlordism. It increasingly used boycotts and other protest methods. The government in Dublin Castle became very strict. O'Brien tried to stop this in Parliament. But arrests continued. Between 1901 and 1902, 13 Irish Members of Parliament were put in jail. By spring 1902, many counties were under strict laws.

The UIL protests highlighted a problem: many families lived on land too small to make a living. Farmers kept pushing for forced land purchase. O'Brien had worked tirelessly for four years. But his efforts had not brought all the benefits he hoped for. Still, he had given the Irish Parliamentary Party new life. The Chief Secretary for Ireland, George Wyndham, saw the terrible situation of the poor in western Ireland. The UIL's existence, along with other pressures, made Wyndham realize it was time to create a new Land Bill for Ireland.

Achievement: The Land Act

In early 1902, Arthur Balfour told Wyndham to prepare a Land Purchase Bill. But when it was introduced in spring, it was not strong enough. The party, following O'Brien's advice, rejected it. So, the bill was withdrawn.

Then, a new and important idea came up. In June, a landlord named Lindsay Talbot Crosbie suggested a meeting. He wanted landlords and farmers to agree on a solution. On September 3, another landlord, Captain John Shawe-Taylor, published a similar idea. He proposed a conference between landlords and tenants. These ideas were important because they showed that some moderate landlords wanted a peaceful solution. The Dublin Castle government encouraged this.

What made Taylor's letter different was that Chief Secretary Wyndham supported it. Wyndham saw a chance to save his Land Bill. He wanted to reintroduce it with terms that both sides agreed on. When Redmond and O'Brien also supported the idea, there was no turning back. Wyndham called for a Land Conference. Its goal was to find a solution that both landlords and tenants could agree on.

Four landlord representatives, led by Lord Dunraven, met with four tenant representatives. The tenant side included William O'Brien MP, John Redmond MP, Timothy Harrington MP, and T. W. Russell MP. After much discussion, the eight delegates met in Dublin on December 20, 1902. Redmond called it "the most significant episode in the public life of Ireland for the last century." After only six meetings, the conference report was published on January 4, 1903. It made 18 recommendations. Most people liked the report.

O'Brien and Redmond met with Sir Anthony MacDonnell from Dublin Castle. On February 16, the UIL and the Irish Parliamentary Party approved the Land Conference terms. The bill to bring peace to Ireland was finally introduced by Wyndham on March 25, 1903. Landowners called it "by far the largest and most liberal measure ever offered to landlords and tenants." On April 16, a League meeting with 3,000 supporters cheered the bill. O'Brien's resolution pledged the Irish nation to "national reconciliation."

O'Brien then helped pass the Land (Purchase) Act 1903 through Parliament. This law was the biggest social change Ireland had seen. It gave generous bonuses to landowners who sold their land. The Irish Land Commission helped new landowners with low-interest payments. O'Brien felt he had led the nationalist movement to support a new policy of "conference plus business." He believed he had started events that would reverse centuries of foreign control. Between 1903 and 1909, over 200,000 farmers became owners of their land because of this Act. O'Brien truly believed that solving the land question was the first step towards Home Rule. Sadly, few others shared his view, and he would face difficulties because of it.

Estrangement: O'Brien Leaves the League

The Land Act passed in August 1903. This led to a strong attack on O'Brien and the Act. Dillon disliked any talks with landlords. He and Thomas Sexton, through their newspaper Freeman's Journal, spoke out against the law. They also criticized the idea of "conciliation" (working together). This disagreement quickly turned O'Brien and Dillon, who were once close friends, into enemies. Davitt also criticized the Act. He thought land should be taken from landlords, not bought.

O'Brien asked his friend Redmond to discipline Dillon and Sexton. But Redmond refused, fearing another party split. Feeling left out, O'Brien told Redmond on November 4, 1903, that he was leaving Parliament. He also left the UIL, stopped publishing his newspaper, and quit public life. Despite pleas from friends, he refused to change his mind.

O'Brien's resignation was a big problem for the party. It caused confusion, like the Parnell crisis in 1890. It had effects in Ireland and abroad. Many local UIL groups stopped working. The League almost died in western Ireland and Dublin. Younger men stopped supporting the parliamentary movement. Davitt reported it was also almost dead in the United States. The League continued to decline across the country. This seriously affected money for both the party and the League.

At a meeting in November 1904, Joseph Devlin replaced O'Brien's loyal general secretary, John O'Donnell. Devlin was a young MP and a close friend of Dillon. He eventually took complete control of the party's organization. This took all power away from O'Brien. Devlin was very loyal to Dillon, who had helped him rise. Dillon relied heavily on Devlin. Devlin controlled the United Irish League and the Catholic group, the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH). He was also a key leader for Ulster Nationalism.

O'Brien had always been worried about the Irish Parliamentary Party working with the AOH. He called it "that sinister sectarian secret society." He often called them the Molly Maguires, or the Mollies. He said they were "the most damnable fact in the history of this country." He strongly attacked them. AOH members were Catholic-nationalists. Their Protestant rivals were the Orange Order. Joseph Devlin was the AOH's Grandmaster. He was now also the General Secretary of the UIL. Devlin was known as "the real Chief Secretary of Ireland." His AOH group grew and spread across Ireland. Even in Dublin, the AOH could gather large crowds. In 1907, Devlin told John Redmond that a UIL meeting would be well attended. He said he could get over 400 AOH members to fill the hall.

Paths Divide

From the start of the UIL, O'Brien believed that Ireland's problems came from politicians. He felt they were out of touch with what ordinary people wanted. After 1900, O'Brien said the party should follow the League. He believed the League truly represented the country's feelings. But what happened was that party members soon controlled the League's decisions and operations. Redmond always made it clear that the party needed to lead in making policies. Once O'Brien started to speak against party policy, he was seen as someone causing trouble. In 1900, O'Brien and Dillon led the UIL. By 1905, Redmond, Dillon, and Joseph Devlin were in charge. O'Brien refused to follow the unwritten rules. So, he lost his place in the League's leadership.

O'Brien later worked with the Irish Reform Association (1904–1905). Then, he joined D. D. Sheehan and his Irish Land and Labour Association. This became his new way to be active in politics. O'Brien also supported plans for more self-government in 1904 and 1907. The UIL rejected these plans. But O'Brien saw them as steps towards Home Rule. These actions angered Dillon's part of the Irish Parliamentary Party. They wanted to stop O'Brien and Sheehan. They regularly criticized their ideas in the party's newspaper.

By 1907, seven MPs were outside the main party. Redmond suggested reuniting the party. A meeting was called for April 1908 in Dublin. For the sake of unity, O'Brien and others rejoined the party. But a year later, O'Brien left for good. This time, he was forced out by Devlin's AOH members. This happened at a rigged meeting in Dublin in February 1909. It was called the "Baton Convention." The dispute was about money for the next stage of the 1909 Land Purchase Act. After this, O'Brien started his new political group, the All-for-Ireland League. This group elected eight independent MPs in the December 1910 elections.

The United Irish League continued to be active. It supported the Irish Parliamentary Party, with many members from the Ancient Order of Hibernians. This continued until the rise of Sinn Féin after World War I began in 1914. From 1918, the UIL was mainly active in Northern Ireland. It stopped existing by the mid-1920s.

|

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |