Irish Land and Labour Association facts for kids

The Irish Land and Labour Association (ILLA) was an important group in Ireland in the early 1890s. It was formed to help small tenant farmers and farm workers get fair rights. The ILLA was also known as the Land and Labour Association (LLA) or League (LLL).

Its groups were active for nearly 30 years. They helped spread ideas about workers' rights. Later, their work became the foundation for new worker and union movements. These groups slowly joined together with the ILLA.

Contents

Why the ILLA Was Needed

In the 1850s, the Tenant Right League started asking for "Three Fs" to help Irish tenant farmers. These were:

- fair rent (not too high);

- fixity of tenure (being able to stay on their land);

- free sale (being able to sell their farm improvements).

Farmers did not have these rights.

Later, some Irish Land Acts were passed in the 1870s and 1880s. But these laws mostly helped farmers. They did not do much for farm workers' homes. Landowners usually built these cottages. The laws made it hard to build new homes for workers.

Farm workers were not very involved in the Irish Land League's "Land War." This war was fought for small tenant farmers from 1879 to 1882. It happened in poorer areas like Connacht and Munster. Conditions were very tough there.

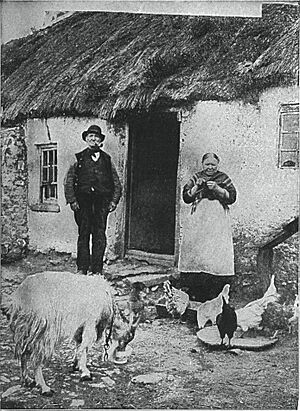

In 1881, about 75% of Irish people lived in the countryside. Many of them were farm workers. About 70% of all farm workers were 'landless.' This meant they did not own any land. Around 60,000 landless workers, plus their families, lived in very poor conditions. Many lived in 40,000 one-room 'cabins'. Sometimes their animals lived with them too.

These workers had two simple demands: a decent home and a small piece of land. Because of this, the Land League also had to start looking at workers' problems.

New laws called the Irish Tenant and Labourers (Land Purchase) Acts started in 1883. The first one was the 1883 Land Purchase (Ireland) Act. These laws were a start to letting tenants buy their farms. At first, over 25,000 tenants became owners.

These laws also allowed for building workers' cottages with small plots of land. Local taxes were supposed to pay for these. But local farmers and Guardians (who ran local services) were the ones paying the taxes. So, they did not want to build many cottages. Very few were built.

Also, farm prices fell, and the weather was bad. Farmers could not pay their rent. They joined the Plan of Campaign to refuse to pay very high rents.

Charles Stewart Parnell was a leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP). He became interested in helping workers when he was in prison. But after he became the IPP leader, he focused on getting Home Rule (self-government for Ireland). The workers' cause was put aside.

By the mid-1890s, fewer than 1,000 cottages were being built each year. These were for small tenant farmers or special workers.

How the ILLA Started

Local groups called Trade and Labour Leagues helped with housing, land, or jobs. They were active in places like Wicklow, Kilkenny, and Tipperary.

The first big steps for workers' groups happened in 1892. The Knights of the Plough was started by Benjamin Pellin in County Kildare. Then, the National Labour League began in Kanturk in January 1893.

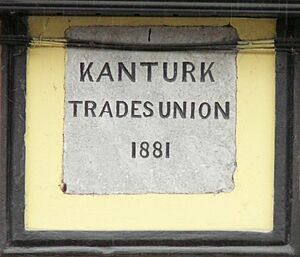

The area around Kanturk in North Cork had been a center for worker protests since the 1860s. Many early unions formed there. In 1869, P. F. Johnson started the Kanturk Labourers' Club. This was the first group to represent farm workers. He also started the Irish Agricultural Labourers' Union in 1873. But these groups did not last long.

The most successful group was the Kanturk Trade and Labour Association, started in 1889. A young man named D. D. Sheehan was its secretary. His family had been evicted from their farm in 1880. This happened during the Land War. His father had followed the "Pay No Rent" idea.

The Kanturk Association grew and became the Duhallow Trade and Labour Association. Michael Davitt also joined this group. But it broke up in 1891 because of a split in the Irish Party.

People realized that giving workers the right to vote in 1884 was not enough. It did not solve their problems. Richer people in the countryside still controlled how laws for workers were put into action. This was very harmful.

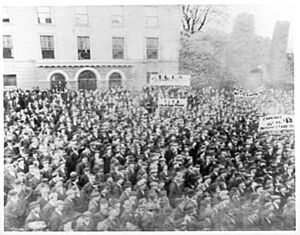

So, workers' groups decided to join together to get more political power. This led to a meeting in Limerick Junction, County Tipperary, on August 15, 1894. There, the Irish Land and Labour Association was officially created. Its founders were D. D. Sheehan as chairman and J. J. O'Shee as secretary.

Sheehan started the ILLA to fight for tenant farmers and workers. He wanted big changes to the old Irish Land Acts. He said workers were "strangers in a strange land, without influence and without rights." The ILLA became the strongest of the worker groups.

The ILLA's work was important all over Ireland. Farmers and workers in Ulster also wanted rights. Their group was the Farmers and Labourers Union. In 1896, the Irish Trade Union Congress suggested that every town in Ireland should have an ILLA branch.

What the ILLA Wanted

The new Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 was a big change. It was like "home rule" for local areas. It took power away from the old, rich landowners. This power went to new Local County Councils. These councils were elected by tenant farmers, town traders, and workers.

These new councils were very important for Ireland. Local people could now make decisions about their own areas. They also created a way for people who wanted Irish Home Rule to get involved. This reduced the power of those who wanted to stay part of the United Kingdom.

The ILLA quickly saw that this new law could help them. Workers could now vote and be elected to councils. The ILLA worked hard to organize workers' votes. They also made sure that workers ran for election.

The ILLA's goals were based on Michael Davitt's ideas. They included:

- land for the people;

- houses for the people;

- work and fair pay for the people;

- education for the people;

- government pensions for old people;

- ground landlords should pay all local rents.

The ILLA wanted to achieve these goals through political action. They used the press and public protests. They did not use violence or strikes.

ILLA's Goals and Challenges

The ILLA aimed to help both small tenant farmers and rural farm workers. Both groups were poor and struggled. Farmers paid too much rent or were evicted. Workers lived in terrible homes. D. D. Sheehan said they lived in "hovels not fit to house the brute beast of the field."

The ILLA wanted farmers to buy their land. They also wanted new and better homes for workers. They pushed for good working conditions and for workers to get small pieces of land.

After the Local Government Act, County and District Councils became responsible for building cottages, fixing roads, and other local work. The ILLA got very involved in making sure local workers and contractors were hired fairly. They also helped settle arguments.

Sometimes, the ILLA had success. Five of their leaders were elected to County Councils. But farmers and landowners still mostly controlled local government. When the ILLA disagreed with rich landowners, they were often kept out of important political actions. This even led to workers being kept out of United Irish League meetings.

Some leaders believed there should not be a separate worker group. They wanted the United Irish League (UIL) to control the ILLA. John Redmond, a political leader, did not want the ILLA to have its own members in Parliament. This showed how rich people wanted to keep control of national politics.

The UIL eventually let the ILLA join national meetings in 1900. But the UIL and the Irish Party did not talk about workers' issues much. They also did little for workers in Parliament. This showed that the ILLA was expected to follow their lead.

In 1901, a special election in Mid-Cork showed the problem. The ILLA candidate, D. D. Sheehan, was doing well. He was accused of not being loyal to the party. This showed the Irish Party's bias against workers.

Helping People Get Homes

By the early 1900s, working-class voters were a new, strong group. Politicians wanted their support during elections. In May 1901, D. D. Sheehan ran for election in Mid-Cork. He focused on workers' rights. He won against the Irish Party's candidate.

Sheehan became a Member of Parliament for Mid-Cork (1901–1918). His election showed the difference between rural workers and the richer, more powerful Irish Party. This difference grew over time.

Rural workers quickly understood how local democracy could help them. They could get land plots, cottages, and jobs on council road-works. The ILLA grew to 98 branches by 1899. By 1904, it had 144 branches, mostly in Cork, Limerick, and Tipperary.

Farmers continued to push for compulsory land purchase. This led to the Land Conference in December 1902. Landlords and tenant farmers met to find a solution. William O'Brien helped guide the tenant farmers. They agreed on a new policy of working together.

O'Brien then worked hard for the Wyndham Land Purchase Act (1903). This law gave generous money to landowners who sold their land.

Sheehan and the ILLA branches helped tenants and landlords make deals. O'Brien and Sheehan formed a Cork Advisory Committee in 1904. This committee helped them negotiate. Many tenants bought land because of this. More tenants in Munster bought land than in any other province. In County Cork alone, over 16,000 tenants bought their land.

This law achieved the ILLA's first big goal: ending "landlordism." Farmers could now own their land. In 1870, only 3% of Irish farmers owned their land. By 1908, nearly 50% did. By the early 1920s, it was 70%.

The 1903 Land Act had a quick positive effect. Reports of threats, boycotts, and people needing police protection dropped a lot. Between 1903 and 1909, over 200,000 small tenant farmers became owners of their farms. By 1914, 75% of farmers were buying their land. This was thanks to the 1903 Act and the later 1909 Act. In total, over 316,000 tenants bought their farms under these laws.

Cottage Ownership

In November 1903, O'Brien left the Irish Party. The party leaders, John Redmond and John Dillon, did not like his idea of working with landowners. They feared it would divide farmers and workers from the Irish Party.

A year later, O'Brien joined D. D. Sheehan's ILLA. He supported Sheehan's demand for homes for farm workers. Before this, workers depended on local councils or landowners for limited housing.

A big step forward happened at a huge worker meeting in Macroom on December 10, 1904. William O'Brien spoke there. His ideas became known as the `Macroom Programme´. These ideas later became law in 1906.

The next phase of the Labourers Acts (1906–1914) began with the important Labourers (Ireland) Act in 1906. Both political groups claimed credit for this law.

This 'Labourers Act' provided a lot of money for building state-sponsored homes. These were for rural workers and other working-class people. The cottages were built by Local County Councils. They changed society a lot by replacing old, unhealthy homes. O'Brien said these laws were almost as amazing as ending landlordism.

In the next five years, over 40,000 new, comfortable homes were built across the Irish countryside. In County Cork, over 7,500 cottages were built with Sheehan and the ILLA. These were known locally as "Sheehans' cottages".

At first, the new landowners did not want to give up an acre of good land for each worker. But they soon saw the benefits. Farmers no longer struggled to find workers. Workers now had their own homes and gardens. They worked together with farmers all year. This had a huge, long-lasting impact on rural Irish society.

In 1841, only 17% of workers lived in homes with five or more rooms. In 1861, one in ten rural families still lived in one-room homes. By 1911, only one percent did. Most workers' cottages were built by 1916. This led to a big drop in diseases like tuberculosis and typhoid. By 1921, up to a quarter of a million people had homes because of the Labourers Acts. This was a social revolution. It was one of the first large public housing projects in the country.

ILLA's Achievements

More money for 5,000 extra cottages was given under the Labourers (Ireland) Act 1911. D. D. Sheehan gave the final speech for this law. He retired from the LLA in 1910. But he stayed active as a leader in the worker movement in Munster.

Around 1912, Ireland was one of the richer small countries in Europe. D. D. Sheehan said in 1921 that because of these housing laws, workers:

"were no longer a people to be kicked and cuffed and ordered about by the schoneens and squireens of the district; they became a very worthy class indeed, to be courted and flattered at election times and wheedled with all sorts of fair promises of what could be done for them".

After solving the main problems for small tenant farmers and farm workers, O'Brien and Sheehan focused on Home Rule. They started a new group called the All-for-Ireland League. Many LLA branches joined this new League.

Challenges and New Beginnings

The Irish Parliamentary Party tried to stop O'Brien's work after he left the party in 1903. They did not like his idea of working with landowners. They thought it was dangerous.

In 1905, J. J. O'Shee, a loyal ally of John Dillon, was asked to form a new group. This group was supposed to be controlled by the party. It was meant to challenge Sheehan's control of the original ILLA. But Sheehan had built his power to help achieve "the great democratic principle of the government of the people by the people and for the people."

A larger part of the ILLA, mostly in Cork, Limerick, Kerry, and Tipperary, followed Sheehan. He renamed it the 'Land and Labour Association' (LLA). Its members served on most local councils. Splits and arguments became common in all national movements after the Parnell split.

O'Brien rejoined the Irish Party in 1908 for unity. But he was forced out again in 1909. This was due to a dispute over money for the 1909 Land Purchase Act. O'Brien then formed a new movement, the "All-for-Ireland League".

By January 1910, more ILLA groups split off. This included groups in Cork city and Dublin. Each claimed credit for the ILLA's earlier successes. Sheehan resigned as LLA president in July 1910. This greatly harmed the workers' movement. People did not know which group they belonged to.

In other counties, branches stayed independent. They had different local activities. Some in Connacht were called the Trade and Labour Association (T&LA).

The Rise of New Labour

By the end of 1919, most ILLA and LLA branches had joined with the growing Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU). Some independent branches stayed active in parts of Munster and Connacht into the 1920s. They eventually joined the ITGWU too. All these groups formed the basis of the new labour movement.

Thomas Johnson, the first leader of the Irish Labour Party, said that the strength of Labour outside cities was partly due to groups like the ILLA.

After the Great War, another 5,000 cottage homes were built. These were for returning soldiers in both parts of Ireland. This was under the Irish Land (Provision for Sailors and Soldiers) Act 1919. It provided cottages, plots, and small new housing areas for veterans. This was done by the "Irish soldiers' and sailors' Land Trust." It worked with the new Irish Free State.

Later Irish governments continued building rural cottages into the mid-20th century. But it was at a slower pace. Local government money then focused more on city housing.

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |