William O'Brien facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William O'Brien

|

|

|---|---|

William O'Brien in 1917

|

|

| Member of Parliament | |

| Constituency | Mallow (1883–1885) South Tyrone (1885–1886) North East Cork (1887–1892) Cork City (1892–1895) Cork City (1900–1909) North East Cork (1910–1910) Cork City (1910–1918) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 2 October 1852 Mallow, County Cork, Ireland |

| Died | 25 February 1928 (aged 75) London, England |

| Political party |

|

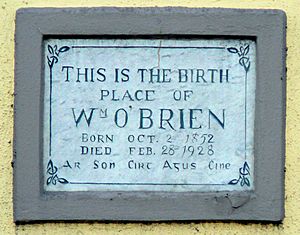

William O'Brien (born October 2, 1852 – died February 25, 1928) was an important Irish leader. He was a nationalist, a journalist, and a politician. He served as a Member of Parliament (MP) in the British Parliament. William O'Brien is best known for his work to change land laws in Ireland. He also tried to find peaceful ways to achieve Home Rule for Ireland. Home Rule meant Ireland would have its own government, but still be part of the United Kingdom.

Contents

- Early Life and Education

- Starting His Career in Journalism

- His Start in Politics

- Editor of United Ireland

- A Voice in Parliament

- Marriage and New Ideas

- Founding the United Irish League

- The Land Act and Housing

- Challenges and New Alliances

- The All-for-Ireland League

- Home Rule and Partition

- Later Years and Legacy

- Works

- Images for kids

Early Life and Education

William O'Brien was born in Mallow, County Cork, Ireland. His father was a clerk for a lawyer. William came from a family with some famous connections, including the statesman Edmund Burke.

He went to school at Cloyne diocesan college. This school taught him to be open-minded about different religions. This experience was very important to him. It shaped his belief that people of all backgrounds in Ireland should work together.

Starting His Career in Journalism

In 1868, William's family faced money problems and moved to Cork City. A year later, his father died. William had to support his mother and siblings because his brothers and sister were ill.

He was a talented writer and quickly found work as a newspaper reporter. He first worked for the Cork Daily Herald. This job helped him become known to the public. He also started studying law at Queen's College (now University College Cork). Even though he didn't finish his law degree, he always felt a strong connection to the college. He later gave his personal papers to the university.

His Start in Politics

From a young age, William O'Brien was interested in politics. He was influenced by the Fenian movement, a group that wanted Irish independence. He also cared deeply about the struggles of Irish tenant farmers. These farmers rented land and often faced very difficult conditions.

He joined the Fenian brotherhood for a while. But he left in the mid-1870s. He felt that trying to gain independence by force would only lead to failure and punishment.

As a journalist for the Freeman's Journal, he wrote articles about the poor conditions of tenant farmers. He visited the Galtee Mountains in 1877 to see their lives firsthand. These articles were some of the first examples of investigative journalism in Ireland. William believed that using newspapers and parliamentary reform could help influence public opinion. He thought this was the best way to achieve Irish Home Rule through peaceful political action.

Editor of United Ireland

In 1878, William met Charles Stewart Parnell, a leading Irish politician. Parnell saw O'Brien's great writing skills. In 1881, Parnell made him editor of United Ireland, the newspaper for the Irish National Land League. This group fought for the rights of tenant farmers.

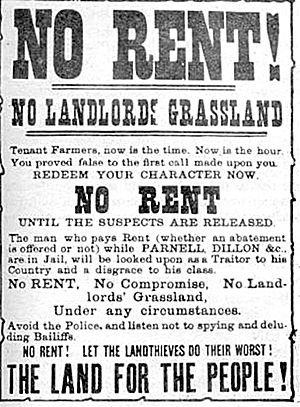

Because of his work with Parnell and the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), O'Brien was arrested. He was put in Kilmainham Gaol in October 1881, along with Parnell and other leaders. While in prison, he wrote the famous No Rent Manifesto. This document encouraged farmers to stop paying rent. It was a big part of the "Land War" against the British government.

A Voice in Parliament

From 1883, William O'Brien served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for various areas in Ireland. He was often arrested and imprisoned because he supported the Land League's protests.

In 1887, O'Brien helped organize a rent strike at Lady Kingston's estate in Mitchelstown, County Cork. During a large protest there, police shot and killed three tenants. This event became known as the Mitchelstown Massacre. Later that year, thousands of people marched in London to demand O'Brien's release from prison. This protest led to clashes with police in Trafalgar Square on Bloody Sunday.

Even in prison, O'Brien continued to protest. He refused to wear a prison uniform. He sometimes wore a special tweed suit in Parliament to challenge the official who had imprisoned him. His time in prison also inspired him to write a popular novel, When We Were Boys, which was published in 1890.

Marriage and New Ideas

In 1890, William O'Brien married Sophie Raffalovich. Sophie came from a wealthy family in Paris. Her money allowed William to be more independent in his political work. It also helped him start his own newspapers. Sophie was a great support to him throughout his life. Their marriage also gave him a love for France and Europe.

By 1891, O'Brien was starting to disagree with Parnell's leadership. After Parnell's personal troubles became public, O'Brien tried to convince him to step down. When Parnell died, the Irish Parliamentary Party split. O'Brien tried to stay neutral. He worked hard to help pass the Second Irish Home Rule Bill in 1893, but it was rejected by the House of Lords.

Founding the United Irish League

In 1895, O'Brien left Parliament for a while. He and his wife moved near Westport, County Mayo. This allowed him to see the difficult lives of farmers in western Ireland.

William O'Brien strongly believed that a mix of protests and political pressure was the best way to achieve goals. On January 16, 1898, he started the United Irish League (UIL) in Westport. Michael Davitt helped him, and John Dillon was also there. The UIL was a new organization that aimed to unite different political groups. Its goals included helping farmers, reforming politics, and achieving Home Rule.

The UIL grew very quickly and became popular across Ireland. It helped bring together the different parts of the Irish Parliamentary Party that had split after Parnell's death. O'Brien's new newspaper, The Irish People, supported the movement. By 1900, O'Brien was a very powerful figure in the nationalist movement, even though he wasn't officially its leader.

The Land Act and Housing

O'Brien then pushed for tenant farmers to be able to buy their land. He worked with some moderate unionists (people who wanted to stay part of the United Kingdom). This led to the Land Conference in 1902. At this meeting, landlords and tenants discussed a peaceful solution. O'Brien led the tenant representatives.

This conference led to the Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903. This was a huge step forward for Ireland. It allowed tenants to buy their land from landlords, which helped solve the long-standing "Irish Land Question." This act changed the lives of many Irish farmers.

Some other politicians, like John Dillon, did not like this act. They thought O'Brien was focusing too much on land purchase and not enough on Home Rule. Because of this disagreement, O'Brien resigned from Parliament in 1903 and left his party for five years. However, the people of Cork insisted on re-electing him in 1904.

William O'Brien also worked with D. D. Sheehan and his Irish Land and Labour Association (ILLA). They focused on providing better housing for farm laborers. These laborers often lived in very poor conditions. O'Brien and Sheehan organized large protests and rallies.

Their efforts led to the groundbreaking Labourers (Ireland) Act (1906). This act provided money for building new homes for rural workers. Over the next five years, more than 40,000 cottages were built, each with an acre of land. This program greatly improved living conditions in rural Ireland. O'Brien believed this act was almost as important as ending landlordism. It helped reduce diseases like tuberculosis and typhoid.

Challenges and New Alliances

In 1908, O'Brien briefly rejoined the Irish Parliamentary Party. However, disagreements continued. At a meeting in 1909, O'Brien and his supporters were shouted down by opponents. This event became known as the "Baton Convention."

After this, O'Brien felt he had to leave the party again. He believed the party was taking a path that would prevent a peaceful Home Rule settlement for all of Ireland. He wanted to find a way for all parts of Ireland, including the Protestant and Unionist communities, to agree on Home Rule. He called this the "Three Cs": Conference, Conciliation, and Consent.

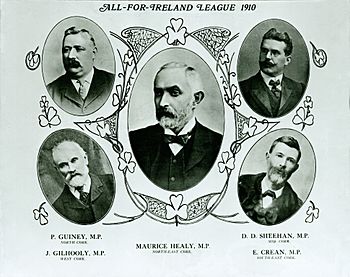

The All-for-Ireland League

These are: Patrick Guiney (North Cork), James Gilhooly (West Cork), Maurice Healy (North-east Cork), D. D. Sheehan (Mid Cork), and Eugene Crean (South-east Cork).

The other MPs elected in January 1910 were: William O'Brien (Cork city), John O'Donnell (South Mayo) and Timothy Michael Healy (North Louth).

In March 1909, William O'Brien started a new group called the All-for-Ireland League (AFIL). Its goal was to achieve an All-Ireland parliament. This parliament would be created with the agreement of both Protestant and Unionist communities. The League was supported by many important Protestant leaders and business people.

Despite health issues, O'Brien returned to politics. In the 1910 elections, eight "O'Brienite" MPs were elected. From 1910 to 1916, O'Brien published the League's newspaper, the Cork Free Press.

O'Brien saw a chance to work with Arthur Griffith's Sinn Féin movement. Both O'Brien and Griffith believed in achieving goals through peaceful political resistance, not violence. They both thought that "Dominion Home Rule," like Canada or Australia had, would be acceptable for Ireland.

Home Rule and Partition

In 1911, O'Brien suggested that Ireland should have full Dominion status. This meant Ireland would be self-governing but still part of the British Empire. A new Home Rule bill was introduced in 1912.

During the debates on the Third Home Rule Bill (1913–1914), O'Brien was worried about resistance from Unionists in Ulster. He disagreed with the idea of forcing Ulster to accept Home Rule. He suggested compromises, like giving Ulster a special veto power. He wanted to keep Ireland united and avoid splitting the country. He said he would "strenuously oppose exclusion" of Ulster.

O'Brien made powerful speeches, calling for generous compromises with Ulster. He warned that if Ireland was divided, it would stay divided. He said he would fight against any plan that would "divide her, and divide her eternally."

However, the main Irish Parliamentary Party leaders, John Redmond and John Dillon, were unwilling to make concessions to Ulster. The Government of Ireland Act 1914 was passed, but it included an amendment that allowed for the partition of Ireland. O'Brien and his followers did not vote for the bill. They called it a "ghastly farce" and a "partition deal."

When World War I began in August 1914, the Home Rule Bill was postponed. O'Brien continued to argue against the division of Ireland. He believed that uniting Irish people, both Nationalists and Unionists, in the war effort could help preserve Ireland's unity. He encouraged Irish Volunteers to join the British army.

Later Years and Legacy

O'Brien was concerned about the rise of Sinn Féin in 1915. He predicted a republican uprising, which happened with the 1916 Rebellion. His newspaper, the Cork Free Press, was shut down in 1916 due to strict censorship rules.

After the Rising, O'Brien believed the political situation had changed. He felt that the Irish Parliamentary Party was no longer effective. He refused to join the Irish Convention in 1917 because his suggestions for including southern Unionists were rejected.

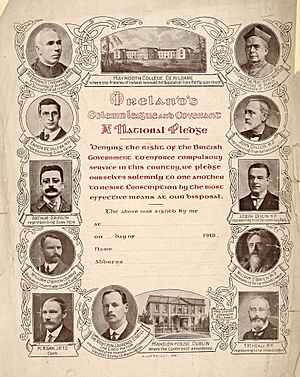

During the anti-conscription crisis in April 1918, O'Brien and his AFIL joined Sinn Féin and other leaders in protests in Dublin. He believed that Sinn Féin, in its moderate form, should represent Irish nationalist interests. He and his party members stepped aside in the December 1918 general elections, allowing Sinn Féin candidates to run unopposed.

William O'Brien disagreed with the creation of the Irish Free State under the Treaty. He still believed that the Partition of Ireland was too high a price for partial independence. He retired from politics and spent his time writing. He passed away on February 25, 1928, in London at the age of 75.

Today, one of the main streets in Mallow, his hometown, is named after him. There is also a Great William O'Brien Street in Cork. His bust is in the Mallow Town Council's Chamber Room, and a portrait hangs in University College Cork.

Works

William O'Brien wrote several books, which include his journalistic articles and political speeches:

- Christmas on the Galtees (1878)

- When we were boys (1890)

- Irish Ideas (1893)

- A Queen of Men, Grace O'Malley (1898)

- Recolections (1905)

- The Downfall of Parliamentarianism (1918)

- Evening Memories (1920)

- The Responsibility for Partition (1921)

- Edmund Burke as an Irishman (1924)

Images for kids

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |