Ireland and World War I facts for kids

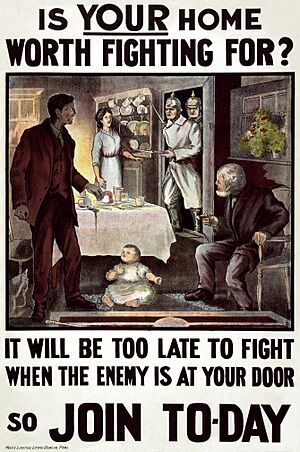

During World War I (1914–1918), Ireland was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The UK joined the war in August 1914 with France and Russia against the Germany, Austria-Hungary, and others.

The war was a complicated time for Irish people, and its memory is still debated. At first, most Irish people, no matter their political views, supported the war. Both nationalist and unionist leaders backed the British war effort. Many Irishmen, both Catholic and Protestant, fought in British forces. Some joined three special Irish divisions. Others served with armies from other parts of the British Empire and the United States.

More than 200,000 men from Ireland fought in the war. They served in many different places. About 30,000 died while serving in Irish regiments of the British forces. As many as 49,400 Irishmen might have died in total.

In 1916, Irish republicans used the war as a chance to declare an independent Irish Republic. They started an armed rebellion in Dublin called the Easter Rising. Germany even tried to help them. Also, in 1918, Britain wanted to make Irishmen join the army (conscription). This caused a lot of anger and was never put into action.

After the war, Irish republicans won the election of 1918. They then declared Ireland's independence. This led to the Irish War of Independence (1919–1922). The Irish Republican Army (IRA) fought against British forces. Many former soldiers fought on both sides. During this war, the British government divided Ireland. The conflict ended with the Anglo-Irish Treaty. This treaty caused a split within Sinn Féin and the IRA. It led to the Irish Civil War (1922–1923) between those who supported the treaty and those who didn't. The pro-treaty side won, and most of the island became the Irish Free State.

The feelings of Irish nationalists about joining the war changed over time. The poet Francis Ledwidge, who was a National Volunteer and died in 1917, showed this change well.

Contents

Ireland Before the Great War

Political Situation in Ireland

Before World War I, Ireland faced a big political problem. This was about "Home Rule," which meant Ireland governing itself.

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 was approved in September 1914. But it was put on hold because of the war. Unionists, mostly in Ulster, strongly opposed Home Rule. In 1913, they formed an armed group called the Ulster Volunteers. They wanted to stop Home Rule or keep Ulster out of it. In response, nationalists formed their own group, the Irish Volunteers. They wanted to protect the rights of Irish people and make Britain keep its promise of Home Rule. It looked like there might be fighting between these two groups in early 1914. The start of World War I stopped this crisis for a while.

Joining the War

About 206,000 Irishmen served in the British forces during the war.

- 58,000 were already in the British Army or Navy before the war. This included regular soldiers, reservists, and officers.

- 130,000 were volunteers who joined during the war.

- 24,000 came from the National Volunteers.

- 26,000 came from the Ulster Volunteers.

- 80,000 had no experience in either group.

Of those who joined during the war, 137,000 went to the British Army. 6,000 joined the Royal Navy, and 4,000 joined the Royal Air Force.

Historian David Fitzpatrick noted that fewer eligible Irishmen volunteered compared to Britain. However, 200,000 Irishmen joining was the largest number of armed men in Irish history. More Protestants volunteered than Catholics overall. But in Ulster, Catholics volunteered as much as Protestants.

The number of volunteers was: 44,000 in 1914, 45,000 in 1915. This dropped to 19,000 in 1916 and 14,000 in 1917. Around 11,000 to 15,655 joined in 1918.

Why Fewer People Joined

Several things caused fewer people to join after 1916.

- Heavy Losses: Irish units suffered many casualties. The 10th Irish Division lost many men in the Gallipoli campaign in 1915. The 16th and 36th Divisions were badly hit at the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

- Church's View: The Catholic Church spoke out against the war in July 1915. The Pope asked all countries to end the war. Irish Catholic Bishops then asked Irish leaders to stop supporting the war.

- Harsh Treatment: Irish troops in the British Army seemed to be treated very harshly. They made up only two percent of the army but received eight percent of all death sentences by military courts. This might have made some Irish people oppose the war.

- Rise of Nationalism: The most important reason was the growth of strong nationalism after the Easter Rising of 1916. This was a rebellion in Dublin by nationalists.

Unlike the rest of the United Kingdom, Ireland was never forced to have conscription (making people join the army). When it was suggested in 1918, it led to the Conscription Crisis of 1918. This was a huge protest, and the idea was dropped.

German Help for Rebels

Irish rebels tried to get help from Germany during the war. Germany sent a ship with over 20,000 Russian rifles and other weapons to help the Easter Rising. However, the ship, the SS Libau, was stopped and sunk by its captain off Fenit, County Kerry. After the Rising, there were talks about sending more weapons in 1917, but it never happened. Roger Casement also tried to form a rebel unit from Irish prisoners of war in Germany, but only 55 men joined.

Irish Army Divisions

Many Irishmen who joined the war in the first year were from what is now the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. They joined new battalions of the eight existing regiments in Ireland.

These battalions became part of the 10th (Irish) Division, the 16th (Irish) Division, and the 36th (Ulster) Division. These were part of Kitchener's New Service Army. Some also joined other British divisions.

Members of the National Volunteers mostly joined the 16th Division. Members of the Ulster Volunteers joined regiments of the 36th Division. The 16th Division became known as excellent shock troops in 1916.

10th (Irish) Division

The 10th (Irish) Division was one of Kitchener's New Army divisions. It was formed in August 1914, mostly from the Irish National Volunteers. It fought in Gallipoli, Salonika, and Palestine. It was the first Irish Division to fight in the war.

The division went to Gallipoli in August 1915. It suffered heavy losses there. In September, it moved to Salonika and fought Bulgarian troops for two years. In September 1917, it moved to Egypt and fought in the Third Battle of Gaza. This battle broke the Turkish defenses in southern Palestine.

The 10th Division often had too few soldiers because of heavy losses and slow recruitment. Because of this, it was filled with soldiers from England. Some historians say it was "Irish in name only." The division was split up in 1918.

16th (Irish) Division

The 16th (Irish) Division was another Kitchener's New Army division. It was formed in Ireland in September 1914, mainly from the National Volunteers. It trained in Ireland and then in England. In December 1915, it moved to France and fought on the Western Front for the rest of the war.

The division first experienced trench warfare at Loos in early 1916. It suffered greatly in the Battle of Hulluch in April. In late July, it moved to the Somme Valley and fought hard in the Battle of the Somme. The 16th Division was key in capturing the towns of Guillemont and Ginchy. It suffered huge losses but gained a reputation as excellent shock troops. The former Nationalist MP Tom Kettle was killed in this battle.

In early 1917, the division played a big part in the Battle of Messines. It fought alongside the 36th (Ulster) Division, earning more recognition. Its main actions ended in the summer of 1917 at the Battle of Passchendaele. The 16th Division was almost wiped out during the German March Spring Offensive in 1918. It was then "reconstituted" in England with mostly English, Scottish, and Welsh battalions.

36th (Ulster) Division

The 36th (Ulster) Division was formed in September 1914. It was made up of members of the Ulster Volunteer Force. Its symbol was the Red Hand of Ulster. The division served on the Western Front for the whole war.

The 36th Division was one of the few divisions to make big gains on the first day on the Somme in July 1916. This came at a high cost, with 5,500 officers and men killed, wounded, or missing in two days. War correspondent Philip Gibbs said their attack was "one of the finest displays of human courage." Four Victoria Crosses were given to 36th Division soldiers in this battle. The division also fought in the Battle of Cambrai and Battle of Messines.

Like the 16th Division, the 36th (Ulster) Division also lost much of its original character by the end of the war. Heavy casualties meant both divisions were filled with British recruits.

Irish Regiments

Irish regiments were linked to recruiting areas in Ireland. The whole of Ireland was a separate military command.

Irish regiments in the war included old professional regiments like the Royal Irish Regiment, Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, and Royal Dublin Fusiliers. These regiments were part of various British divisions.

After the war started, these regiments raised new battalions in Ireland for the three New Irish Divisions. When the 10th and 16th Irish Divisions were broken up in 1918, their remaining battalions were spread among other British divisions.

Irishmen also joined other Irish regiments based in England, Scotland, and Wales. These included cavalry regiments and infantry regiments like the Irish Guards. Many Irish immigrants in other parts of the world also joined local Irish units, such as in Canada and the United States.

Where the War Was Fought

Western Front

First Shot

The first British engagement in Europe was by the 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards on August 22, 1914. Corporal Edward Thomas fired the first British army shot in Europe.

Mons, Givenchy, 1914

The Germans were advancing through Belgium. On August 27, the 2nd Battalion Royal Munster Fusiliers was chosen to cover the retreat of the British Expeditionary Force during the Battle of Mons. The Munsters made a brave stand, holding off Germans who were much stronger for over a day. This allowed their division to escape.

The Irish Guards also suffered heavily at Mons, fighting a difficult retreat. The experience of these regiments showed how much the highly trained pre-war British Army was damaged in 1914. By the end of 1914, many regiments were shattered. This meant new volunteers from Kitchener's New Army, including the Irish Divisions, were needed.

St Julien, 1915

During the 2nd Battle of Ypres in May, the 2nd Royal Dublin Fusiliers were almost wiped out by a German poison gas attack. Only 21 out of 666 soldiers survived.

Dublin, 1916

As war casualties grew, the Irish Volunteers kept training. They started the Easter Rising in Dublin on April 24. About 1,200 Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army members took over the city center. Around 5,000 British troops were sent to stop the rebellion. More troops arrived from other parts of Ireland and England. The 4th, 5th, and 10th Royal Dublin Fusiliers took part.

By the end of the week, 16,000 British troops were in Dublin. 62 rebels were killed, and 132 British Army and police died. Many civilians were also killed or wounded. After the Rising, 16 rebel leaders, including the seven who signed the Proclamation of Irish Independence, were executed by the British Army without trial.

The executions helped turn Irish nationalist support away from the old political party and towards Sinn Féin.

Hulluch, 1916

A German gas attack on April 27 in the Battle of Hulluch caused 385 casualties. The 16th (Irish) Division stayed in Loos-en-Gohelle until August. They then moved to the Somme, but not before suffering 6,000 casualties, including 1,496 deaths.

Battle of the Somme, 1916

The Battle of the Somme began on July 1. On that day, 60,000 Allied soldiers were killed or wounded. The 36th (Ulster) Division suffered 5,500 casualties, with 2,000 killed. Other Irish units also fought and suffered heavy losses. The battle continued until November.

The 16th (Irish) Division captured Guillemont on September 2 and Ginchy on September 9. A London newspaper praised "How the Irish took Ginchy – Splendid daring of the Irish troops."

Messines Ridge, June 1917

After the Dublin Fusiliers fought well in April, the 16th (Irish) and 36th (Ulster) Divisions fought together in June 1917. They captured the Belgian village of Wijtschate in the Battle of Messines. This battle had the largest number of Irish soldiers ever on a battlefield. They took all their targets on time, even with few supporting tanks. The battle was a complete success. One of those who died was 56-year-old Major Willie Redmond, an MP and brother of John Redmond, a leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party.

Passchendaele, July 1917

In July 1917, both divisions moved under General Sir Hubert Gough. He ordered an advance east of Ypres towards strong German positions. The British artillery preparation was not good enough. By mid-August, the 16th (Irish) Division had over 4,200 casualties, and the 36th (Ulster) Division had almost 3,600 casualties. This was more than half their numbers. The poet Francis Ledwidge was killed on July 31.

Spring Offensive, March 1918

The 16th (Irish) Division and the 36th (Ulster) Division were almost completely destroyed in the great German spring offensive in March 1918. Over 6,400 men in the 16th and over 6,100 in the 36th were killed. This led to the April conscription crisis. Irish soldiers were then moved to other divisions. They took part in the final Hundred Days Offensive which pushed the Germans back and ended the war.

Middle East Fronts

Gallipoli, 1915

Fighting on the Western Front was stuck. So, a new plan was made to open a second front in the east. The Ottoman Empire controlled the Bosporus sea passage. The Royal Navy tried to sail through the Dardanelles in March but lost ships. So, Irish, British, French, Australian, and New Zealand troops were sent to Gallipoli for a land invasion.

In the Gallipoli Campaign, an invasion was tried in April. But Turkish defenses kept the troops close to the beach. Irish battalions suffered huge losses during the V beach Landing at Cape Helles. This was the most important landing, defended by strong Turkish machine gun posts.

The main force landed from the SS River Clyde. Waves of men were cut down as they tried to reach shore. Few succeeded, but they kept trying. Their efforts to create a foothold failed, with over 600 Irish casualties in 36 hours.

Serbia, 1915

When Bulgaria invaded Serbia, both Greece and Serbia asked for help. A force from the 10th (Irish) Division sailed from Gallipoli to Salonika on September 29. They fought on the Bulgarian front during the Macedonian campaign. The Royal Dublin 6th/7th Battalions and Munsters 6th/7th Battalions fought to take the village of Jenikoj. They suffered 385 casualties.

In December, the 10th Division, still in summer uniforms, suffered many casualties from severe snow and frost. They were ordered to retreat. They stayed in Salonika and rebuilt their strength in 1916.

Greece, 1916

The Bulgarians, with German help, crossed the Greek border in May 1916. The 10th Division fought the Bulgarians in August and September. They crossed the Struma River and took the village of Yenikoi. They retook it after a Bulgarian counterattack, but at the cost of 500 men. The division was then moved to Palestine.

Palestine, 1917

The 10th Division arrived in Egypt in September. After training, they joined the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. After the Third Battle of Gaza and the Turkish retreat in November, the 10th Division returned to the front. They faced sniper fire on the way to the capture of Jerusalem, which they entered easily in December. With relatively few losses, the division had achieved its goals. After many defeats, they finally tasted victory.

France, 1918

Heavy losses on the Western Front after the great German spring offensive led to 60,000 men being moved from Palestine to France. This included ten battalions of the 10th Division. They arrived in France in June 1918 and joined the Hundred Days Offensive.

Casualties

The number of Irish deaths in the British Army was recorded as 27,405. This was about 14 percent of Irish soldiers, similar to other British forces. The National War Memorial in Dublin states 49,400 Irish soldiers died. However, this number includes all fatalities in the Irish Divisions, not just those born in Ireland. Only about 71 percent of casualties in these divisions were from Ireland.

A 2017 study found that 29,450 men born or living in the 26 counties that became the Irish Free State died in the war. Another study counts 10,300 war deaths from Northern Ireland. This means the total confirmed Irish death toll is about 40,000.

Around 1,000 more Irish-born men died serving with the United States Army.

The dead were buried near the battlefields. Seriously injured soldiers were sent to Ireland to recover. Those who died of their wounds in Ireland were buried in the Grangegorman Military Cemetery, unless their families claimed their bodies. Most buried there are from World War I.

After the War

The war ended on November 11. About 210,000 Irish men and women had actively served in British forces, and more in other Allied armies.

When the Irish Divisions were disbanded, about 100,000 war veterans returned to Ireland. This means 70,000 to 80,000 chose to live elsewhere. Reasons for this included high unemployment in Ireland and the rise of strong nationalism, which was often unfriendly to those who had served in British forces.

In 1919, a law was passed to provide houses for soldiers returning from the war. Most of these houses were built after the Irish Free State was formed. They aimed to help ex-servicemen return to civilian life.

When the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921) began, ex-servicemen faced a difficult situation. Some, like Tom Barry, who had served in the British Army in WWI, joined the IRA. Many others joined paramilitary police forces, like the Black and Tans and Auxiliary Division, who fought against the rebels. In County Clare, for example, 15 war veterans joined the Auxiliaries, and 25 joined the Black and Tans. In Northern Ireland, many ex-servicemen joined the Ulster Special Constabulary, an armed police force. Over half of its 32,000 recruits were veterans of the Great War.

About 10% of the Black and Tans and 14% of the Auxiliaries were Irishmen. These groups committed many terrible acts during the War of Independence. Because of this, many nationalists were unwilling for many years to recognize the role Irishmen played in the World War on Britain's side.

Most ex-servicemen did not take an active part in the conflict. However, some were suspected and threatened by the IRA. For example, 29 ex-servicemen were shot dead in County Cork as suspected informers. In total, 82 ex-servicemen were killed by the IRA as informers.

When most of Ireland left the United Kingdom in 1922 to form the Irish Free State, five regular Irish regiments were disbanded. These included the Royal Dublin Fusiliers and the Royal Munster Fusiliers. Other Irish regiments, like the Irish Guards, continued to serve.

Thousands of these ex-servicemen joined the new National Army of the Free State. This happened after the Irish Civil War began in June 1922. The National Army grew to 58,000 men by May 1923. About one-fifth of its officers and half of its soldiers were Irish ex-servicemen from the British Army. Men like Martin Doyle and Emmet Dalton brought much combat experience to the new army.

Remembering the War

In the Irish Free State and Republic of Ireland

Because of the complex history, Irishmen who fought and died in the Great War were not officially remembered for many years. Many nationalists were hostile to those who had fought for Britain.

From 1919 to 1925, Remembrance Day was held in Dublin. But it often had riots between nationalists, unionists, and ex-servicemen. In 1925, after Irish Independence, it was moved to the Phoenix Park, outside the city center. The IRA sometimes attacked people selling poppies and disrupted Remembrance Day events.

The Irish government gave money in 1927 to build a Great War Memorial in Dublin. But they put it in Islandbridge, outside the city center, not in a more central location.

The Memorial Park opened in 1948. But it wasn't until 2006 that the Irish state held an official event there to remember the Irish dead of World War I. The President of Ireland, Mary McAleese, and the Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, marked the 90th anniversary of the Battle of the Somme.

Since 1986, the National Day of Commemoration is held each July. It remembers "all Irish people who died in past wars or United Nations peacekeeping missions."

A Cross of Sacrifice was unveiled at Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin, on July 31, 2014. It honors Irish soldiers who died in both world wars. The President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, and the Duke of Kent unveiled it.

In Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland, the war was seen by unionists as a sign of British loyalty. They have always officially remembered the dead of both world wars on Armistice Day. For unionists, their part in World War I was a strong symbol of their loyalty to Britain.

Even though Catholics in Northern Ireland joined the war as often as Protestants, they were often left out of the war's commemoration. It became almost entirely a Unionist event.

Today, at the Somme, there is a large monument to the 36th (Ulster) Division at Thiepval. But there are only two small Celtic crosses for the 16th (Irish) Division.

The 16th (Irish) Division was mostly Catholic and nationalist. For much of the 20th century, its story was almost removed from the history of the Great War. At the same time, the achievements of the 36th (Ulster) Division became a big part of Northern Irish Protestant culture.

Memorials

Here are some places that remember Irish people who served and died in the Great War:

- Irish National War Memorial Gardens

- Island of Ireland Peace Park in Messines, Belgium.

- Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres, Belgium.

- Ulster Tower Memorial in Thiepval, France.

- Pery Square War Memorial, Limerick

Images for kids

-

John Dillon speaks at a rally against conscription in 1918.

-

The Derry Guildhall stained-glass window. It honors the Three Irish Divisions: the 36th (left), and the 10th and 16th (right).

See also

- Garden of Remembrance (Dublin), for those who fought in Irish nationalist rebellions

- Irish World War I recipients of the Victoria Cross

- Ireland rugby players killed in WWI

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |