German spring offensive facts for kids

Quick facts for kids German spring offensive |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of World War I | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

The German Spring Offensive, also known as the Kaiserschlacht (meaning "Kaiser's Battle"), was a series of major attacks by the German army during World War I. These attacks happened on the Western Front starting on March 21, 1918.

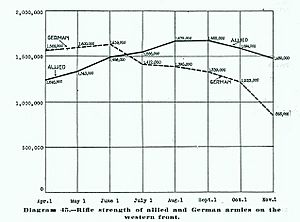

By 1917, the United States had joined the war. Germany knew that if the U.S. sent many soldiers to Europe, they would be very hard to beat. So, Germany decided to try and win the war quickly. They wanted to defeat the Allies before the American troops could fully arrive. Germany had a temporary advantage in numbers. This was because nearly 50 of their army divisions were now free. They had been fighting Russia, but Russia had left the war after signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

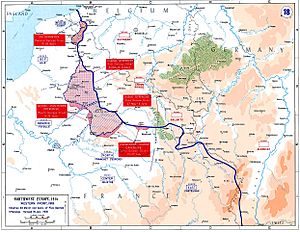

There were four main German attacks, given secret names: Michael, Georgette, Gneisenau, and Blücher-Yorck. Michael was the biggest attack. Its goal was to break through the Allied lines. The Germans hoped to surround the British forces and defeat them. If the British were defeated, Germany hoped France would give up. The other attacks were smaller. They were meant to distract the Allies from the main attack on the Somme River. The Germans did not have a clear plan for what to do after the attacks started. They often changed their goals as the fighting went on.

Once the German army started moving forward, it was hard for them to keep up the attack. This was partly because of problems with supplies. The fast-moving stormtrooper units could not carry enough food or ammunition. The army also could not bring in supplies and new soldiers fast enough. The Allies focused their main forces on important areas. These included the ports on the English Channel and the railway hub of Amiens. They left less important areas, which had been destroyed by years of fighting, with fewer defenders. Within a few weeks, the danger of a German breakthrough had passed. However, related fighting continued until July.

The German army made the biggest advances on the Western Front since 1914. They took back much land they had lost in 1916–17. They also captured some new land. But these gains came at a high cost. Germany suffered many casualties for land that was not very important and was hard to defend. The offensive failed to win the war for Germany. Some historians call it a pyrrhic victory. This means a victory that costs too much. In July 1918, the Allies had more soldiers again. This was because American troops had arrived. In August, the Allies used their new numbers and better tactics to launch a counter-attack. This attack, called the Hundred Days Offensive, made the Germans lose all the land they had gained. It also led to the collapse of the Hindenburg Line and Germany's surrender in November.

Contents

German Plans for Attack

New Tactics for the Offensive

The German army trained many of its best soldiers as "stormtroopers." These special units learned to move quickly. They would sneak past enemy front lines. Their goal was to attack enemy headquarters, artillery, and supply areas behind the lines. They also aimed to capture land fast. Regular soldiers would then follow to deal with any remaining enemy strong points.

This new tactic gave Germany an early advantage. However, it meant their best soldiers suffered the most casualties. This also lowered the quality of the rest of the army. The Germans also did not have fast-moving forces like cavalry. These forces could have helped them quickly use their gains. This meant the infantry had to keep pushing forward, which was very tiring.

To help with the first breakthrough, a German artillery officer named Georg Bruchmüller created a new artillery plan. It was called the Feuerwalze (meaning "rolling fire"). This plan was very effective and used shells wisely. It had three parts:

- First, a short, sudden bombardment on enemy command centers and communications.

- Second, destroying their artillery.

- Third, attacking the enemy's front-line soldiers.

The bombardment was always short to keep it a surprise. Germany had many heavy guns and lots of ammunition in 1918, which made this tactic possible.

Allied Defenses

How the Allies Prepared

The Allies had also changed their defense plans. They put fewer troops on their front line. They moved their reserve soldiers and supply areas further back. This kept them out of range of German artillery. They learned this from Germany's successful defenses in 1917.

In theory, the front line was a "forward zone." It was lightly held by snipers and machine-gun posts. Behind this, out of range of German field artillery, was the "battle zone." Here, the Allies planned to fight hard against any attack. Even further back was a "rear zone." This area held reserve troops ready to counter-attack.

However, the Allies had not fully set up these defenses everywhere. Especially in the area held by the British Fifth Army, the defenses were not complete. There were also not enough troops to fully defend the area. The rear zone was only marked out, and the battle zone had weak points. This allowed German stormtroopers to get through.

Operation Michael: The Main Attack

On March 21, 1918, Germany launched its biggest attack, Operation Michael. It hit the British Fifth Army and part of the British Third Army.

The artillery attack began at 4:40 AM on March 21. The bombardment hit targets over an area of 150 square miles [390 km2]. This was the biggest artillery attack of the entire war. Over 1,100,000 shells were fired in just five hours...

The Germans were lucky that morning. A thick fog helped their stormtroopers sneak deep into British positions without being seen. By the end of the first day, the British had lost many soldiers. The Germans had broken through the British Fifth Army's lines in several places. After two days, the Fifth Army was retreating quickly. Many isolated British strong points were surrounded and captured.

The German commander, Ludendorff, did not fully follow his own stormtrooper tactics. He also lacked a clear overall plan. He kept attacking strong British units, which cost his army many soldiers. On March 28, he launched another attack near Arras (Operation Mars). But the British defenses there were strong and ready. There was no fog to hide the German attackers. This attack failed quickly, and Ludendorff called it off.

The German breakthrough happened near where the French and British armies met. The French commander, General Pétain, sent help slowly at first. This worried the British. To improve coordination, the Allies appointed French General Ferdinand Foch to lead all Allied forces in France.

The German advance also slowed because of supply problems. The stormtroopers carried only a few days' worth of supplies. They relied on new supplies arriving quickly from the rear. But the German army struggled to bring supplies forward. This gave the Allies more time to send in reinforcements. The advance was also difficult because they were crossing land destroyed by earlier battles.

After a few days, the German attack began to stop. The soldiers were tired, and it was hard to move artillery and supplies forward. Fresh British and Australian troops arrived to defend the important railway center of Amiens. The Allied defense became stronger. After failing to capture Amiens, Ludendorff stopped Operation Michael on April 5.

The Germans had advanced a long way, which was impressive for the time. However, it was not a true victory. They lost many of their best soldiers. Important places like Amiens and Arras remained in Allied hands. The land they gained was also hard to defend later.

The Allies lost about 255,000 soldiers (British, British Empire, and French). They also lost many artillery pieces and tanks. But they could replace these losses with new equipment and American soldiers. Germany lost 239,000 soldiers. Many of these were their special stormtroopers, who were very hard to replace. The initial German joy at their success soon turned to disappointment. It became clear that the attack had not won the war.

Operation Georgette: Attacking the Ports

Operation Michael had made the British send troops to defend Amiens. This left other areas weaker. These areas included the railway route through Hazebrouck and the Channel ports like Calais and Dunkirk. If Germany could capture these ports, it would be a huge blow to the British.

The attack, called Georgette, started on April 9 with another Feuerwalze bombardment. The main attack hit an open, flat area defended by the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps. The Portuguese soldiers had been in the trenches for a year and were very tired. They were being replaced by fresh British divisions, but the Germans attacked before the change was complete. The Portuguese 2nd Division was left to defend a long, open front alone.

The German attack, with eight divisions, hit the Portuguese 2nd Division very hard. They fought bravely but were quickly surrounded and overwhelmed. The Portuguese 2nd Division lost over 7,000 men. The British 40th Division also quickly collapsed. This created a gap that helped the Germans surround the Portuguese. However, the British 55th Division held their ground well.

The next day, the Germans attacked further north. They forced British defenders to retreat and captured the Messines Ridge. By the end of the day, the few British reserve divisions were struggling to hold a line along the River Lys.

Without more French help, people feared the Germans could reach the ports within a week. The British commander, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, issued a famous order on April 11. He said, "With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause, each one of us must fight on to the end."

But the German attack stalled again. They had supply problems and their flanks (sides) were exposed. Counterattacks by British, French, and Anzac forces slowed and then stopped the German advance. Ludendorff ended Georgette on April 29.

Like Michael, the losses were similar for both sides, about 110,000 soldiers each. Again, the Germans did not achieve their main goals. Hazebrouck stayed in Allied hands. The Germans now held a dangerous salient (a bulge in the front line) that could be attacked from three sides. The British gave up some less important land they had captured earlier. This freed up more divisions to fight the Germans.

Operation Blücher–Yorck: Towards Paris

While Georgette was stopping, Germany planned a new attack on French positions. This was meant to draw Allied forces away from the Channel ports. The goal was still to split the British and French armies and win the war before more American troops arrived. American troops had already started fighting in smaller battles. For example, the US 1st Division launched its first attack at Cantigny on May 28, 1918.

The German attack, Blücher–Yorck, began on May 27. It took place between Soissons and Reims. This area was partly held by four tired British divisions that were resting. The defenses here were not strong. Because of this, the Feuerwalze was very effective. The Allied front lines quickly collapsed. The French commander had put too many troops in the front trenches. This meant there were no local reserves to slow the Germans down once the front broke.

Despite some French and British resistance, German troops advanced to the Marne River. It seemed like Paris might be captured. There was panic in Paris. German long-range guns had been shelling the city since March 21. Many citizens fled, and the government made plans to leave.

Again, losses were similar for both sides: about 127,000 Allied and 130,000 German casualties by June 6. German losses were mostly from their valuable assault divisions, which were hard to replace.

Operation Gneisenau: Extending the Attack

Ludendorff had planned another big attack to defeat the British further north. But he made a mistake. He moved reserve troops from Flanders to the Aisne area. This was to support the success of Blücher–Yorck. However, the Allied commanders, Foch and Haig, did not move too many of their reserves to the Aisne.

Ludendorff then launched Operation Gneisenau on June 9. He wanted to extend the Blücher–Yorck attack westward. This would draw even more Allied reserves south. It would also widen the German salient and link up with the German salient near Amiens.

The French had learned about this attack from German prisoners. Their deep defenses helped reduce the impact of the German artillery bombardment. Even so, the German advance was impressive. Twenty-one German divisions attacked along a 23 mi (37 km) front. They advanced 9 miles (14 km) despite strong French and American resistance. But at Compiègne, a sudden French counter-attack on June 11 surprised the Germans. Four French divisions and 150 tanks attacked without warning. This stopped the German advance. Gneisenau was called off the next day.

Losses were about 35,000 Allied and 30,000 German soldiers.

Last German Attack: The Peace Offensive

Ludendorff then postponed his planned attack in the north. Instead, he launched the Friedensturm (Peace Offensive) on July 15. This was another attempt to draw Allied reserves south from Flanders. It also aimed to expand the salient created by Blücher–Yorck to the east.

An attack east of Reims was stopped by the French deep defenses. In many areas, the Germans did not get past the French Forward Zone. They did not break through the main French Battle Zone anywhere. The Germans had lost air superiority, so their air force could not provide much support. This meant they had no surprise.

Although German troops southwest of Reims crossed the Marne River, the French launched a major attack on July 18. This attack threatened to cut off the Germans in the salient. Ludendorff had to pull most of his troops out of the Blücher–Yorck salient by August 7. His planned attack in the north was finally cancelled. The Allies now clearly had the upper hand. They soon began the Hundred Days Offensive, which ended the war.

Aftermath

The German Spring Offensive was a huge effort. Germany gained a lot of land. But they lost many of their best soldiers, who were hard to replace. The Allies, with new American troops, were able to recover. The offensive did not win the war for Germany. Instead, it weakened their army and set the stage for the Allied counter-attacks that ended World War I.

See also

- Journey's End, a play set during the early stages of the offensive

- Spring Offensive, a poem by Wilfred Owen

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |