Hundred Days Offensive facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hundred Days Offensive |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of World War I | |||||||

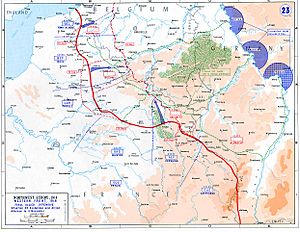

Allied gains in late 1918 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Strength on 11 November 1918: |

Strength on 11 November 1918: |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 18 July – 11 November: 1,070,000 |

18 July – 11 November: ~100,000+ killed 685,733 wounded 386,342 captured 6,700 artillery pieces Breakdown

Men and materiel captured, by country

2,500 killed 5,000 captured 10,000 wounded |

||||||

The Hundred Days Offensive was the final major series of attacks by the Allies during World War I. These attacks took place on the Western Front from August 8 to November 11, 1918. The offensive began with the Battle of Amiens.

This period of fighting led to the German armies losing their will to fight and retreating. It ultimately resulted in the end of World War I. The Hundred Days Offensive isn't just one battle. It's a name for many quick Allied victories that started with the Battle of Amiens.

Contents

The Start of the Offensive

In March 1918, Germany launched big attacks on the Western Front. These attacks, like Operation Michael, had slowed down by July. The German forces had reached the Marne River but couldn't break through Allied lines completely.

After Operation Marne-Rheims ended in July, the main Allied commander, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, ordered a counter-attack. This became the Second Battle of the Marne. The Germans realized their position was weak and pulled back from the Marne.

Foch felt it was time for the Allies to go on the attack. Many American soldiers had arrived in France. Their presence gave new energy to the French armies. The American commander, General John J. Pershing, wanted his army to fight on its own. The British Army also had many new soldiers. These troops came from other campaigns or had been held back in Britain.

Foch agreed with Field Marshal Douglas Haig, who led the British forces. Haig suggested attacking near the Somme, east of Amiens. This area was chosen for several reasons:

- It was the border between British and French armies, allowing them to work together.

- The flat countryside of Picardy was good for tanks.

- The German defenses there were weaker. Australian troops had been constantly raiding them.

Key Battles of the Offensive

Battle of Amiens

The Battle of Amiens started on August 8, 1918. More than 10 Allied divisions attacked. These included Australian, Canadian, British, and French forces. They also had over 500 tanks. The Allies planned carefully and completely surprised the Germans.

The attack was led by Australian and Canadian troops. They broke through the German lines. Tanks then attacked German positions behind the front lines, causing panic. By the end of the day, the Allies had created a 24-kilometer (15 mi) gap in the German line. They took 17,000 prisoners and captured 330 guns.

German losses on August 8 were about 30,000 soldiers. The Allies lost about 6,500 soldiers killed, wounded, or missing. The German commander, Erich Ludendorff, called it "the Black Day of the German Army." This showed how much German morale had dropped.

The Allied advance continued for three more days. But it wasn't as successful as the first day. The fast advance meant that supporting artillery and supplies couldn't keep up. Also, the Germans brought in more soldiers to defend. By August 10, the Germans began to pull back. They moved towards the strong Hindenburg Line.

Fighting on the Somme

On August 15, 1918, Marshal Foch wanted Haig to keep attacking at Amiens. However, the attack was slowing down. Troops were running out of supplies, and German reserves were moving to that area. Haig refused. Instead, he prepared a new attack by the British Third Army at Albert. This new offensive began on August 21.

This new attack was a success. It pushed the German Second Army back across a 55-kilometer (34 mi) front. Albert was captured on August 22. On August 26, the British First Army made the attack even wider. Bapaume fell on August 29.

As more artillery and supplies arrived, the British Fourth Army also restarted its attack. The Australian Corps crossed the Somme River on the night of August 31. They broke through German lines at Mont St Quentin and Péronne. General Henry Rawlinson, commander of the British Fourth Army, called the Australian advances from August 31 to September 4 the greatest military achievement of the war.

By September 2, the Germans had been forced back close to the Hindenburg Line. This was the same line they had attacked from in the spring.

Breaking the Hindenburg Line

Foch now planned a huge attack on the German lines in France. This was called the Grand Offensive. Different Allied armies would attack from various directions. Their goal was to meet up near Liege in Belgium.

The main German defenses were the Hindenburg Line. This was a strong series of forts and trenches. It stretched from Cerny on the Aisne River to Arras. Before Foch's main offensive, the Allies cleared out remaining German positions west and east of this line. This happened at Havrincourt and St Mihiel on September 12, and at Epehy and Canal du Nord on September 18.

The first attack of Foch's Grand Offensive began on September 26. The American Expeditionary Force launched the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Two days later, the Belgian Army and the British Second Army attacked near Ypres in Flanders. Both attacks made good progress at first. But then they slowed down because of problems getting supplies, especially in the American area.

On September 29, Haig launched the main attack on the Hindenburg Line. This was the Battle of St. Quentin Canal by the British 4th Army. By October 5, the British Fourth Army had completely broken through the Hindenburg defenses. Rawlinson wrote that he would never have thought of attacking the Hindenburg Line if the Germans hadn't shown signs of weakening. He believed it would have been impossible to break through if the Germans were as strong as they had been two years earlier.

Meanwhile, on October 8, the Canadian Corps led the 1st and 3rd British armies. They broke through the Hindenburg Line at the Battle of the Canal du Nord.

This major breakthrough forced the German High Command (their military leaders) to accept that the war had to end. The clear signs of failing German morale also convinced many Allied commanders and politicians that the war could end in 1918. Before this, everyone had been preparing for a big attack in 1919.

German Retreat and the End of the War

Throughout October, the German armies were forced to retreat. They moved back through the land they had gained in 1914. However, their retreat never turned into a complete collapse. The Allies kept pushing the Germans back towards a key railway line. This line, from Metz to Bruges, had supplied the entire German front in Northern France and Belgium for most of the war.

As the Allied armies reached this railway line, the Germans had to leave behind more and more heavy equipment and supplies. This made their morale even worse and reduced their ability to fight back.

Allied and German forces continued to suffer many casualties. Rearguard actions (small battles fought by retreating forces to slow down the enemy) took place at Ypres, Kortrijk, Selle, Valenciennes, the Sambre, and Mons. Fighting continued until the very last minutes before the Armistice took effect. The Armistice, a ceasefire agreement, began at 11:00 AM on November 11, 1918.

One of the last soldiers to die was Canadian Private George Lawrence Price. He died two minutes before the armistice. The very last soldier to die was American Henry Gunther, who died at 10:59 AM, less than a minute before the Armistice began.

Images for kids

-

Troops of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, 36th (Ulster) Division, advancing from Ravelsburg Ridge to the outskirts of Neuve Eglise, 1 September 1918

See also

In Spanish: Ofensiva de los Cien Días para niños

In Spanish: Ofensiva de los Cien Días para niños