Philippe Pétain facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Marshal

Philippe Pétain

|

|

|---|---|

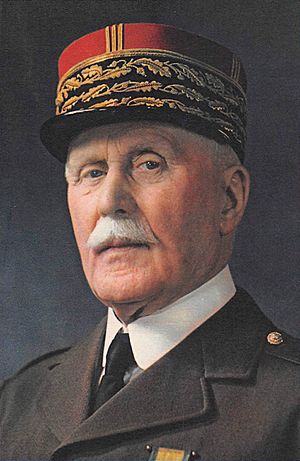

Pétain in 1941

|

|

| Chief of the French State | |

| In office 11 July 1940 – 20 August 1944 |

|

| Prime Minister | Pierre Laval Pierre-Étienne Flandin François Darlan |

| Preceded by | Albert Lebrun (President of the Republic) |

| Succeeded by | Charles de Gaulle (Chairman of the Provisional Government of the Republic) |

| Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 16 June 1940 – 11 July 1940 |

|

| President | Albert Lebrun |

| Deputy | Camille Chautemps Pierre Laval Pierre-Étienne Flandin François Darlan |

| Preceded by | Paul Reynaud |

| Succeeded by | Pierre Laval |

| Deputy Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 18 May 1940 – 16 June 1940 |

|

| Prime Minister | Paul Reynaud |

| Preceded by | Camille Chautemps |

| Succeeded by | Camille Chautemps |

| Minister of War | |

| In office 9 February 1934 – 8 November 1934 |

|

| Prime Minister | Gaston Doumergue |

| Preceded by | Joseph Paul-Boncour |

| Succeeded by | Louis Maurin |

| Chief of Staff of the Army | |

| In office 30 April 1917 – 16 May 1917 |

|

| Preceded by | Robert Nivelle |

| Succeeded by | Ferdinand Foch |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain

24 April 1856 Cauchy-à-la-Tour, France |

| Died | 23 July 1951 (aged 95) L'Île-d'Yeu, France |

| Spouse |

Eugénie Hardon Pétain

(m. 1920) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Army |

| Years of service | 1873–1944 |

| Rank | General of division |

| Battles/wars | World War I Rif War World War II |

| Awards | Marshal of France Military Medal |

| Conviction(s) | Treason |

| Criminal penalty | Death; commuted to life imprisonment |

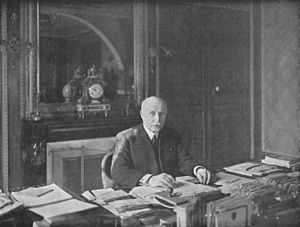

Philippe Pétain (born April 24, 1856 – died July 23, 1951) was a French general who became a Marshal of France at the end of World War I. During that war, he was known as "The Lion of Verdun" for his role in a major battle. From 1940 to 1944, during World War II, he led the French government known as Vichy France, which worked with the Axis powers. Pétain was 84 years old when he became Prime Minister, making him the oldest person to lead France.

During World War I, Pétain led the French Army to victory at the long Battle of Verdun. After some army problems, he became Commander-in-Chief and helped the soldiers regain their confidence. He remained in charge for the rest of the war and became a national hero. Between the two World Wars, he led the French Army during peacetime and served as a government minister twice. People called him "The Old Marshal."

When France was about to fall to Germany in June 1940, Prime Minister Paul Reynaud resigned. He suggested that President Albert Lebrun appoint Pétain in his place. Pétain's government then decided to sign agreements to stop fighting with Germany and Italy. The government moved to the town of Vichy in central France. There, they voted to change France into an authoritarian government called the French State, or Vichy France, which cooperated with the Axis powers. After Germany and Italy took over more of France in November 1942, Pétain's government worked very closely with the German military.

After World War II, Pétain was put on trial and found guilty of serious charges against his country. He was first sentenced to death. However, because of his old age and his service in World War I, his sentence was changed to life in prison. His journey from a regular soldier to a French hero, and then to a leader who worked with the enemy, led Charles de Gaulle to say that Pétain's life was "successively ordinary, then glorious, then regrettable, but never unimportant."

Contents

Early Life and Military Beginnings

Pétain was born on April 24, 1856, in Cauchy-à-la-Tour, a small town in northern France. He came from a farming family. His mother died when he was very young, and he was raised by relatives after his father remarried. He went to a Catholic boarding school and later prepared for the Saint-Cyr Military Academy.

Joining the French Army

Pétain joined the French Army in 1873 when he was accepted into Saint-Cyr. After graduating in 1878, he served in various places with different groups of chasseurs, who were elite light infantry soldiers. He slowly moved up in his career.

Pétain's career was not very fast because he disagreed with the French Army's idea of charging forward without thinking. He believed that "firepower kills," meaning that guns and artillery were more important. His ideas proved right during World War I. He became a captain in 1890 and a major in 1900. In 1904, he became a professor of infantry tactics at the École Supérieure de Guerre (War College). He became a lieutenant-colonel and then a full professor in 1908. By 1910, he was a colonel.

Unlike many French officers, Pétain mostly served in France itself. He did not serve in French colonies like Indochina or Africa, though he did take part in the Rif War in Morocco. In 1911, he commanded the 33rd Infantry Regiment. A young officer named Charles de Gaulle served under him and later said that Pétain taught him "the Art of Command." By the spring of 1914, Pétain was 58 years old and had been told he would never become a general. He had even bought a house for his retirement.

World War I: A Hero Emerges

Leading in Battle

Pétain led his soldiers at the Battle of Guise in August 1914. The next day, he was promoted to brigadier-general. He then commanded the 6th Division during the First Battle of the Marne. Just over a month later, in October 1914, he was promoted again to lead the XXXIII Corps. After leading his corps in the 1915 Artois Offensive, he was given command of the Second Army in July 1915. He became known as one of the most successful commanders on the Western Front.

The Battle of Verdun

Pétain commanded the Second Army at the start of the Battle of Verdun in February 1916. This battle lasted for nine months and was one of the longest and bloodiest of the war. During the battle, he was promoted to Commander of Army Group Centre, which included 52 divisions. Instead of keeping the same soldiers at Verdun for months, he rotated them out after only two weeks. This helped keep their spirits up.

Pétain also made sure that trucks constantly brought artillery, ammunition, and fresh troops to Verdun using a special road called the "Voie Sacrée" (Sacred Way). This was very important in stopping the German attacks. He used his belief that "firepower kills!" by using French artillery, which fired millions of shells at the Germans. Pétain famously said, "On les aura!" (meaning "We'll get them!"). Another famous quote, "Ils ne passeront pas!" ("They shall not pass!"), is often linked to him, but it was actually said by Robert Nivelle, who took over command of the Second Army at Verdun in May 1916. At the end of 1916, Nivelle was promoted above Pétain to become the French Commander-in-Chief.

Restoring Army Morale

Because of his strong reputation as a leader who cared for his soldiers, Pétain briefly served as Army Chief of Staff starting in April 1917. He then became the Commander-in-Chief of the entire French army. He replaced General Nivelle, whose attack in April 1917 failed and caused many soldiers to refuse orders (mutinies). These mutinies affected almost half of the French infantry divisions on the Western Front.

Pétain helped restore the soldiers' morale by talking to them, giving tired units rest, allowing them to go home for visits, and using fair discipline. He held many trials for mutineers, but most of the death sentences were changed to prison time. The mutinies were kept secret from the Germans and were not fully known until many years later.

Pétain led some successful but limited attacks in late 1917. He waited for American troops to arrive in large numbers and for new Renault FT tanks to be ready. He famously said, "J'attends les chars et les Américains" ("I am waiting for the tanks and the Americans").

The War's End

In 1918, Germany launched major attacks on the Western Front. One of these attacks in March 1918 threatened to separate the British and French forces. Pétain was concerned and suggested retreating towards Paris. This led to a meeting where Ferdinand Foch was appointed as the Allied Generalissimo, meaning he would coordinate all Allied forces. Pétain eventually sent 40 French divisions to help the British and secure the front.

Pétain proved to be a skilled leader against the Germans, both in defending and counter-attacking. By the time of the last German attacks, Pétain was able to defend well and launch counter-offensives with new French tanks and American help. After the war ended, Pétain was made a Marshal of France on November 21, 1918.

Between the Wars: A Respected Figure

A National Hero

After World War I, Pétain was seen as "one of France's greatest military heroes." He received his Marshal's baton in a public ceremony in Metz in December 1918. He was also present at the signing of the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919, which officially ended the war. With peace, his role as Commander-in-Chief ended. In January 1920, he was appointed Vice-Chairman of the Supreme War Council, which was France's highest military position. He held this role until 1931.

Pétain suggested plans for a large tank and air force, but the government said they could not afford them. Instead, they cut military spending. This led to discussions about building a line of forts along the border with Germany. This line, later called the Maginot Line, became very important to Pétain. He strongly supported it because of his experience at Verdun, where forts played a key role.

Leading in Morocco

Pétain was appointed Inspector-General of the Army in February 1922. In 1925, he was made the sole Commander-in-Chief of French Forces in Morocco. He led a major campaign against the Rif tribes, working with the Spanish Army. This campaign was successful by the end of October. He received a Spanish military medal for his service.

Concerns About Defense

Pétain was very concerned about cuts to military spending and the reduction in the length of national service. He believed these changes would weaken France's army. He argued that France needed a strong army to defend itself and its colonies.

In 1931, Pétain was elected a member of the Académie française, a very respected French institution. He continued to argue for more military spending, especially for air defense. However, the economic situation worsened, and the government made more cuts to the defense budget.

Minister of War

In February 1934, Pétain was asked to join the new French government as Minister of War. He accepted this role reluctantly. He worked to improve the army, especially by getting rid of a previous plan to reduce the number of officers. He also improved training for soldiers. However, other military leaders still reported that the French Army was not ready for a German attack. Pétain kept asking the government for more money for the army. He also wanted to increase the time young men had to serve in the military from two to three years, but this did not happen.

Pétain met Hermann Göring, a high-ranking Nazi official, in 1934. They talked about their experiences in World War I. Göring later spoke highly of Pétain, calling him "a man of honour."

Speaking Out Against Policies

After leaving his role as Minister of War, Pétain continued to speak out about defense policy. He wrote articles criticizing France's reservist system and its lack of modern air power and tanks. These articles appeared just before Adolf Hitler announced that Germany was building up its army and air force.

Some people argue that Pétain, as France's most senior soldier, should share some blame for the poor state of French weapons before World War II. However, he was just one person on a large committee, and governments often cut military budgets. Also, the Treaty of Versailles had limited Germany's military, so there seemed to be no urgent need for huge spending until Hitler came to power. French tanks were often used to support infantry, and modern rifles and machine guns were not widely produced. French artillery had not been updated since 1918. Because of these problems, the French Army faced the German invasion in 1940 with outdated weapons.

World War II: Leading Vichy France

Joining the Government in Crisis

In March 1939, Pétain became the French ambassador to Spain. When World War II began in September, he was offered a position in the government but turned it down. However, after Germany invaded France in May 1940, Pétain joined the government of Paul Reynaud as Deputy Prime Minister. Reynaud hoped that the hero of Verdun would inspire the French Army to fight harder.

By May 26, the Allied lines were broken, and British forces were leaving France at Dunkirk. French military leaders, including Pétain, believed the situation was hopeless. British officials urged France not to sign an armistice, saying that if French ports were taken by Germany, Britain would have to bomb them. Pétain reportedly told Reynaud, "your ally now threatens us."

On June 8, with Paris threatened, the government prepared to leave the city, but Pétain was against it. He argued that France's interests came before Britain's.

The Fall of France

On June 10, the government moved from Paris to Tours. The Commander-in-Chief, Maxime Weygand, said that "the fighting had become meaningless." He and others wanted to sign an armistice. On June 11, Winston Churchill flew to France. He suggested that the French continue fighting using guerrilla warfare, but Pétain replied that this would destroy the country. Pétain also reminded Churchill that France no longer had many divisions to fight, and Britain should be providing more help.

On June 12, the cabinet met again, and Weygand again called for an armistice. He worried about disorder and a possible Communist uprising in Paris. Pétain supported Weygand, saying he was the only one who truly knew what was happening.

The government moved to Bordeaux on June 14. On June 15, Reynaud suggested that the army should lay down its arms so the fight could continue from abroad. Pétain was initially sympathetic. However, Weygand convinced Pétain that Reynaud's idea would be a shameful surrender. The cabinet then voted to ask about armistice terms.

Pétain Becomes Head of State

On June 16, President Franklin D. Roosevelt replied to France's request for help with only vague promises. Pétain then offered his resignation, which would have brought down the government. President Lebrun convinced him to wait for Churchill's reply. Churchill's telegram arrived, agreeing to an armistice if the French fleet moved to British ports. This was not acceptable to François Darlan, the Navy Minister, who said it would leave France defenseless.

That afternoon, the British government offered joint nationality for French and British citizens in a "Franco-British Union." Some French ministers found this insulting. The cabinet meeting on June 16 was divided, with some wanting to fight on and others favoring an armistice.

President Lebrun reluctantly accepted Reynaud’s resignation as Prime Minister on June 17. Reynaud suggested that Marshal Pétain be appointed in his place, which Lebrun did that day in Bordeaux. Pétain already had a team ready for his new government.

Leading the French State

Signing the Armistice

A new government with Pétain as its head was formed. On June 17, 1940, Pétain made his first radio broadcast to the French people, asking Germany to stop fighting and share its peace terms.

Many French people welcomed Pétain as a savior. Meanwhile, General de Gaulle, who was no longer in the cabinet, arrived in London and called for resistance on June 18. Few people listened to his call at first.

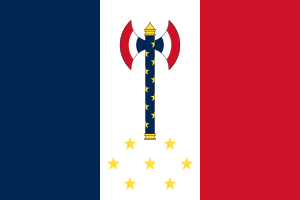

On June 22, France signed an armistice at Compiègne with Germany. This agreement gave Germany control over northern and western France, including Paris and the Atlantic coast. The rest of France, about two-fifths of its pre-war territory, remained unoccupied. Paris was still the official capital. On July 1, the French government moved to Vichy, where the empty hotels were suitable for government offices.

Changes to the Government

On July 10, the French Parliament met and voted to give the cabinet the power to create a new constitution. This effectively ended the Third Republic. Most historians and later French governments consider this vote illegal. The next day, Pétain formally took almost complete power as "Head of State."

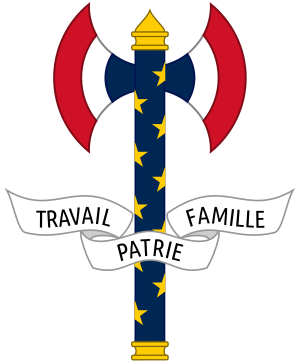

Pétain was a traditional leader and quickly blamed the Third Republic for France's defeat. His government became authoritarian. The national motto "Freedom, equality, brotherhood" was replaced with "Work, family, fatherland." He issued new laws that ended the presidency, stopped parliament, and gave him full power to appoint and fire ministers and civil servants. He also gained the power to pass laws and choose his successor. One of his advisors said he had more power than any French leader since Louis XIV.

The new government used its powers to take harsh actions. They fired civil servants who supported the Republic, created special courts, and passed anti-Jewish laws. They also imprisoned opponents and foreign refugees. Censorship was put in place, and freedom of speech and thought were largely ended.

The government also created a "French Legion of Fighters," which included groups loyal to the new regime. Pétain supported a traditional, rural France and rejected international ideas. As a retired military commander, he ran the country like an army.

Working with Germany

Within months, Pétain signed laws that discriminated against Jewish people. These laws prevented Jews from working in many jobs and allowed foreign Jews to be detained.

Pétain's government was recognized by other countries, including the U.S., until Germany occupied the rest of France. Neither Pétain nor his deputies offered much resistance to German requests for help for the Axis powers. When Hitler met Pétain in October 1940 to discuss France's role in the "new European Order," Pétain's handshake with Hitler caused anger in London. This likely influenced Britain's decision to support the Free French forces. France remained formally at war with Germany, but was opposed to the Free French. After British attacks in July and September 1940, the French government became more afraid of the British and chose to cooperate with the Germans. Pétain agreed to the creation of a French militia called the Milice, which worked with German forces to fight against the French resistance.

Pétain's government agreed to German demands for large amounts of manufactured goods and food. They also ordered French troops in the French colonial empire to defend French territory against any attackers, whether Allied or not.

On November 11, 1942, German forces invaded the unoccupied zone of Southern France. This happened after Allied landings in North Africa and Admiral Darlan's agreement to support the Allies. Although the French government still existed in name, Pétain became a figurehead, meaning he had little real power. The Germans had ended the idea of an "independent" government at Vichy. However, Pétain remained popular and visited different parts of France as late as 1944. When he arrived in Paris on April 28, 1944, large crowds cheered him.

Forced Relocation to Germany

On August 17, 1944, as the Allies advanced, the Germans forced Pétain to move to the northern zone. Pétain refused, but the Germans threatened to bomb Vichy. After asking the Swiss ambassador to witness the German threats, Pétain gave in. On August 20, 1944, Pétain was taken against his will by the German army to Belfort.

After France was liberated, on September 8, 1944, Pétain and other members of the Vichy cabinet were moved by the Germans to Sigmaringen enclave in Germany. They formed a government-in-exile there until April 1945. However, Pétain refused to take part in this government because he had been forced to leave France. On April 5, 1945, Pétain wrote to Hitler, saying he wanted to return to France. He never received a reply. However, on his birthday almost three weeks later, he was taken to the Swiss border. Two days later, he crossed into France.

After the War

Trial and Imprisonment

The new French government, led by de Gaulle, put Pétain on trial for serious charges against his country. The trial took place from July 23 to August 15, 1945. Pétain, wearing his Marshal of France uniform, mostly stayed silent during the trial. He only made an initial statement saying that the court did not have the right to try him.

At the end of the trial, Pétain was found guilty of all charges. The jury sentenced him to death by one vote. However, because of his old age, the court asked that the sentence not be carried out. De Gaulle, who was the head of the government, changed the sentence to life imprisonment because of Pétain's age and his important military service in World War I. After his conviction, Pétain lost all his military ranks and honors, except for his title of Marshal of France.

To prevent riots, de Gaulle ordered Pétain to be immediately taken by plane to Fort du Portalet in the Pyrenees mountains. He stayed there from August to November 1945. The government later moved him to a fort on the Île d'Yeu, a small island off the French Atlantic coast.

Later Years and Death

Many people, including foreign governments and important figures, asked for Pétain to be released from prison. However, the French government was unstable and did not want to risk being unpopular by releasing him. Even U.S. President Harry S. Truman asked for his release in 1946 and offered him political asylum in the U.S., but it was denied.

Although Pétain was in good health for his age when he was imprisoned, by late 1947, he started having memory problems. By 1949, he was often confused and suffering from hallucinations. He also began to have heart problems and could not walk without help.

On June 8, 1951, President Vincent Auriol was told that Pétain did not have much longer to live. He changed Pétain's sentence to confinement in a hospital. The news was kept secret until after the elections, but by then, Pétain was too ill to be moved to Paris.

Pétain died in a private home on the Île d'Yeu on July 23, 1951, at the age of 95. He was buried in a local cemetery there. Some people called for his remains to be moved to the grave prepared for him at Douaumont cemetery among the war dead.

De Gaulle later wrote that Pétain’s life was "successively ordinary, then glorious, then regrettable, but never unimportant."

In February 1973, Pétain's coffin was stolen from the cemetery by extremists. They demanded that President Georges Pompidou allow his re-burial at Douaumont cemetery. Police found the coffin a few days later, and it was reburied on the Île d'Yeu.

Places Named After Him

Several places were named after Pétain. Mount Pétain, Pétain Creek, and Pétain Falls in the Canadian Rockies were named after him in 1919. However, these names were removed in 2021 and 2022.

Hengshan Road in Shanghai was called "Avenue Pétain" between 1922 and 1943. There is also a Petain Road in Singapore. In Pinardville, New Hampshire, a neighborhood with French-Canadian roots, there is a Petain Street from the 1920s, alongside streets named after other World War I generals.

New York City Honor

On October 26, 1931, Pétain was honored with a ticker-tape parade down Manhattan's Canyon of Heroes. The New York City Mayor's Office later considered removing the sidewalk marker for Pétain because of his role in World War II.

Personal Life

Pétain was a bachelor until he was in his sixties. He was known for having many relationships. After World War I, Pétain married his former girlfriend, Eugénie Hardon (1877–1962), on September 14, 1920. They remained married until his death. Eugénie had a son from her first marriage, Pierre de Hérain, whom Pétain did not like.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Philippe Pétain para niños

In Spanish: Philippe Pétain para niños

- Battle of France

- 1917 French Army mutinies

- Historiography of the Battle of France

- Hôtel du Parc

- Vichy France

- List of ministers in Vichy France

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |