Battle of Mons facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Mons |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of the Frontiers of the First World War | |||||||||

British soldiers from the Royal Fusiliers resting in the town square at Mons before entering the line prior to the Battle of Mons. The Royal Fusiliers faced some of the heaviest fighting in the battle and earned the first Victoria Cross of the war. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 2 corps 1 cavalry division 1 cavalry brigade 300 guns |

4 corps 3 cavalry divisions 600 guns |

||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 1,638 | 2,000–5,000 | ||||||||

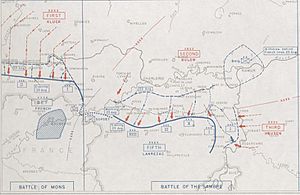

The Battle of Mons was the first big fight for the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in the First World War. It was part of a larger series of battles called the Battle of the Frontiers. In these battles, the Allied armies fought against Germany along the borders of France.

At Mons, the British Army tried to hold a defensive line along the Mons–Condé Canal. They were up against the advancing German 1st Army. Even though the British fought bravely and caused many more casualties to the Germans, they were eventually forced to retreat. This happened because the Germans had more soldiers, and the French Fifth Army suddenly pulled back, leaving the British side open.

The British retreat from Mons was supposed to be a short, planned move. But it turned into a two-week journey, taking the BEF all the way to the edge of Paris. There, they finally counter-attacked with the French in the Battle of the Marne.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

Britain declared war on Germany on August 4, 1914. A few days later, on August 9, the BEF started sailing to France. Unlike other European armies, the BEF was quite small in 1914. Germany and France each had over a million soldiers. The BEF had about c. 80,000 soldiers, who were all professional, long-service volunteers and reservists.

The British soldiers were very well trained. They were especially good at firing their Lee–Enfield rifles quickly and accurately. An average British soldier could hit a target 15 times a minute from 300 yards (270 m) away. This skill helped them a lot in the battles of 1914.

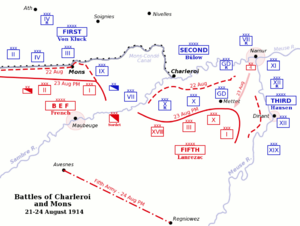

The Battle of Mons was part of the wider Battle of the Frontiers. German armies were moving forward, clashing with Allied armies along the borders of France and Belgium. The BEF was on the far left side of the Allied line. This meant they were directly in the path of the German 1st Army. This German army was the outer part of a huge plan called the Schlieffen Plan. The plan aimed to defeat the Allied armies and force them out of northern France and Belgium.

The British arrived in Mons on August 22. That afternoon, General Charles Lanrezac of the French Fifth Army asked the BEF to attack the German flank. The French Fifth Army was fighting the German 2nd and 3rd armies at the Battle of Charleroi. Sir John French, the British commander, refused this request. Instead, he agreed to hold the line of the Condé–Mons–Charleroi Canal for 24 hours. This would stop the German 1st Army from threatening the French left side. The British spent the day digging in along the canal.

Getting Ready for Battle

British Preparations

At Mons, the BEF had about 80,000 men. This included a Cavalry Division, a separate cavalry brigade, and two corps. Each corps had two infantry divisions.

- I Corps, led by Sir Douglas Haig, had the 1st and 2nd Divisions.

- II Corps, led by Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien, had the 3rd and 5th Divisions.

Each division had 18,073 men and 5,592 horses. They also had 24 Vickers machine guns (two per battalion) and many artillery guns.

The II Corps was on the left side of the British line. They set up defenses along the Mons–Condé Canal. The I Corps was positioned at a right angle to the canal, along the Mons–Beaumont road. This was to protect the BEF's right side if the French had to retreat from Charleroi. Because of this, the I Corps was not very involved in the main battle. The German attack mostly hit the II Corps.

The most important part of the battlefield was a loop in the canal. It stuck out from Mons towards the village of Nimy. This loop was hard to defend and became the main focus of the battle.

The first contact between the two armies happened on August 21. A British bicycle scouting team met a German unit near Obourg. Private John Parr became the first British soldier killed in the war. The first real fighting began on the morning of August 22. At 6:30 a.m., the 4th Royal Irish Dragoons set up an ambush for German lancers outside Casteau. When the Germans retreated, Captain Hornby and his men chased them with their sabres. Captain Hornby became the first British soldier to kill an enemy in the Great War, fighting on horseback. Drummer E. Edward Thomas is said to have fired the first shot for the British Army, hitting a German soldier.

Later that day, the BEF's Chief of Intelligence, Colonel George Macdonogh, warned Sir John French that three German army corps were advancing directly towards them. But the Field Marshal chose to ignore this warning. He still planned to advance towards Soignies.

German Preparations

The German 1st Army, led by Alexander von Kluck, was advancing towards the British. This army was very powerful, with about c. 18,000 men per 1 mi (1.6 km) of front.

On August 22, the German 1st Army expected to meet British troops. They thought the British were on the left side of the French Fifth Army, from Mons to Maubeuge. Earlier, British cavalry had been seen at Casteau, north-east of Mons. A British airplane was shot down near Maubeuge. More reports showed that British troops were moving towards Mons.

Kluck wanted to advance south-west to surround the British. But he was told to advance south instead on August 23. Late on August 22, reports confirmed that the British were holding the Canal du Centre crossings from Nimy to Ville-sur-Haine. This showed where the British were, except for their far left side.

On August 23, the German 1st Army began to advance north-west of Maubeuge. The weather was cloudy and rainy, which kept German planes on the ground. News came that many troops were arriving at Tournai by train, so the German advance was paused to check these reports. German corps began attacking the canal crossings.

The Battle Begins

Morning Attacks

At dawn on August 23, German artillery started firing on the British lines. All day, the Germans focused on the British soldiers in the loop of the canal. At 9:00 a.m., the first German infantry attack began. They tried to cross four bridges over the canal in the loop.

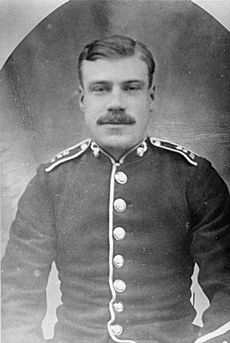

Four German battalions attacked the Nimy bridge. It was defended by a company of the 4th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers, and a machine-gun team led by Lieutenant Maurice Dease. The Germans first advanced in close columns, like they were on a parade ground. This made them easy targets for the British riflemen. The British hit German soldiers from over 1,000 yards (910 m) away, cutting them down with rifle, machine-gun, and artillery fire. The British rifle fire was so heavy that some Germans thought they were facing many machine-guns.

The first German attack failed with heavy losses. The Germans then switched to a more spread-out formation and attacked again. This attack was more successful, but the British defenders were still outnumbered. The Royal Irish Fusiliers at the Nimy and Ghlin bridges held on with help from reinforcements and the amazing bravery of two machine-gunners.

At the Nimy bridge, Lieutenant Dease took control of his machine gun after his team was killed or wounded. He kept firing even though he was shot several times. After a fifth wound, he was taken away and later died. Private Sidney Godley took over and covered the Fusiliers' retreat. When it was his turn to leave, he broke the gun by throwing parts into the canal, then surrendered. Both Dease and Godley were awarded the Victoria Cross, the first ones of the First World War.

Captain Theodore Wright of the Royal Engineers also showed great bravery. He tried to blow up five bridges over the canal. He destroyed the Jemappes pass, but was hit by a shell fragment while setting charges at Mariette. He tried again, but fell into the canal and had to give up. He also received a Victoria Cross for his actions. Theodore Wright was killed in action the next month.

To the right of the Royal Fusiliers, the 4th Battalion, Middlesex Regiment and the 1st Battalion, Gordon Highlanders, were also heavily attacked. They suffered many casualties but held the bridges with reinforcements and artillery support. The Germans then attacked the British defenses along the straight part of the canal to the west. They used nearby fir tree plantations for cover and fired machine-guns and rifles at the British. This attack hit the 1st Battalion, Royal West Kent Regiment and the 2nd Battalion, King's Own Scottish Borderers, very hard. Despite many losses, they pushed back the Germans all day.

The Retreat Begins

By the afternoon, the British position in the canal loop was impossible to hold. The 4th Middlesex had lost 15 officers and 353 other ranks killed or wounded. To the east, German units had started crossing the canal in large numbers, threatening the British right side. At Nimy, Private Oskar Niemeyer swam across the canal under British fire to operate machinery that closed a swing bridge. He was killed, but his actions reopened the bridge, allowing more Germans to attack the 4th Royal Fusiliers.

Sir John French, the British commander, still thought an advance was possible. However, by 3:00 p.m., the 3rd Division was ordered to pull back from the loop to positions south of Mons. The 5th Division also retreated later that evening. By nightfall, the II Corps had set up a new defensive line through several villages. The Germans had built temporary bridges and were approaching in great strength.

News arrived that the French Fifth Army was retreating, which left the British right side dangerously exposed. At 2:00 a.m. on August 24, the II Corps was ordered to retreat south-west into France. They were to reach defensible positions along the Valenciennes–Maubeuge road. Sir John finally realized that a quick retreat was necessary to save the BEF.

This unexpected order to retreat from prepared defenses meant the II Corps had to fight many small, fierce battles against the Germans. For the first part of the withdrawal, the 15th Brigade acted as a rearguard. On August 24, they fought holding actions at Paturages, Frameries, and Audregnies. At Audregnies, the 1st Battalions of the Cheshire and Norfolk Regiments stopped the German advance despite being outnumbered and suffering huge losses. They also caused many casualties to the Germans. Their refusal to fall back without orders led Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien to say that these battalions "saved the BEF."

At Wasmes, parts of the 5th Division faced a big attack. German artillery began firing at daybreak, and at 10:00 a.m. German infantry attacked. They advanced in columns and were "mown down like grass" by British rifle and machine-gun fire. For two more hours, British soldiers held off German attacks. They then retreated in good order. On the far left of the British line, two brigades of the 5th Division were threatened by a German flanking move. They called for help from the cavalry. The 2nd Cavalry Brigade and two artillery batteries helped them. The cavalry dismounted and, with the artillery, covered the retreat of the brigades in four hours of intense fighting.

German 1st Army's Advance

On August 23, the German 18th Division advanced and started firing on British defenses near Maisières and St. Denis. Some German troops crossed the canal east of Nimy with few losses. They reached the railway beyond in the early afternoon. The 36th Brigade captured bridges at Obourg against strong resistance. After this, the defenders of Nimy slowly pulled back. The bridges to the north were captured at 4:00 p.m., and the town was stormed. Mons was captured without a fight, except for a small skirmish.

By 11:00 a.m., reports showed that the British were in St. Ghislain and at the canal crossings to the west. Intelligence reports from August 22 had noted 30,000 troops moving towards Mons. On August 23, 40,000 men were seen south of Mons, with more troops arriving. British cavalry had been forced back by German cavalry. Kluck ordered his corps to advance.

The German III Corps had to cross fields to reach the canal, where all bridges were destroyed. The 5th Division captured Tertre but was stopped by rifle fire from across the canal. They eventually managed to cross the canal against strong resistance. As dark fell, Wasmuel was occupied, but attacks on St. Ghislain were stopped by machine-gun fire. The 6th Division was counter-attacked at Ghlin before advancing towards higher ground south of Jemappes. The British in the village stopped the division with rifle fire. Small groups managed to cross the canal and capture the village with artillery support. The rest of the division crossed the canal and pursued the British until dark.

The German IV Corps arrived in the afternoon. They found that the British had blown up the bridges. Repairs took until 9:00 a.m. on August 24. The German advance was slowed by these destroyed bridges. The cavalry divisions advanced towards Denain to cut off the British retreat.

During the night, the British launched several counter-attacks, but no German divisions were forced back over the canal. At dawn, the IX Corps continued its advance, pushing against British rearguards. The advance was slowed by the obstacles of Maubeuge and other German corps blocking the roads.

On the III Corps front, the 6th Division attacked Frameries at dawn. It held out until 10:30 a.m., then the British began to retreat. St. Ghislain was attacked by the 5th Division behind an artillery barrage. The 10th Brigade crossed the canal and took the village in house-to-house fighting. A British defensive line along the Dour–Wasmes railway stopped the German advance until 5:00 p.m., when the British withdrew. The German infantry were tired and stopped their pursuit.

The IV Corps found that the British had blown the bridges and withdrawn. Repairs took time, and the advance was slow. The German cavalry divisions advanced towards Denain, fighting French troops along the way.

What Happened Next

Casualties

J. E. Edmonds, the British official historian, reported "just over" 1,600 British casualties. Most of these were in the two battalions that defended the canal loop. He wrote that German losses "must have been very heavy." Some historians estimate German losses to be around c. 5,000 men. Other records suggest about 2,145 German dead and missing and 4,932 wounded from August 20–31.

The Battle's Legacy

The Battle of Mons has become a famous story in British history. It's seen as an amazing victory against huge odds. Two myths grew from the battle:

- The Angels of Mons: A miraculous tale that angelic warriors, sometimes described as phantom longbowmen, saved the British Army by stopping the German troops.

- The Hound of Mons: A story that a German scientist created a hellhound to attack British soldiers at night.

Soldiers of the BEF who fought at Mons received a special medal called the 1914 Star. It was often called the Mons Star.

It was said that on August 19, 1914, Kaiser Wilhelm issued an order saying: ". . . my soldiers to exterminate first the treacherous English; walk over Field Marshal French's contemptible little Army." This led British soldiers, known as "Tommies", to proudly call themselves "The Old Contemptibles." However, no proof of this order has ever been found in German records, and the ex-Kaiser denied giving it. Some believe it was made up for propaganda.

The Germans built the St Symphorien Military Cemetery to remember the German and British soldiers who died. A tall granite monument stands in the center of the cemetery. It has a German message: "In memory of the German and English soldiers who fell in the actions near Mons on the 23rd and 24th August 1914."

Originally, 245 German and 188 British soldiers were buried there. Later, more British, Canadian, and German graves were moved to the cemetery. More than 500 soldiers are now buried in St. Symphorien. The cemetery also holds the graves of two soldiers believed to be the first (Private John Parr, August 21, 1914) and the last (Private Gordon Price, November 11, 1918) Commonwealth soldiers killed in the First World War.

A bronze plaque was put on a wall of Obourg railway station. It remembers British soldiers who died around Obourg. This includes an unnamed soldier who is said to have stayed behind at the station to cover his comrades' retreat.

Images for kids

See also

- Angels of Mons

- HMS Mons, ships of the Royal Navy named in honour of the battle

- La Ferté-sous-Jouarre memorial

- Order of battle at Mons

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |