Roger Casement facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Roger Casement

|

|

|---|---|

Casement by Sarah Purser, 1914

|

|

| Born |

Roger David Casement

1 September 1864 |

| Died | 3 August 1916 (aged 51) Pentonville Prison, London, England

|

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Monuments |

|

| Occupation | Diplomat, poet, humanitarian activist |

| Organisation | British Foreign Office, Irish Volunteers |

| Title | a knighthood for his efforts on behalf of the Amazonian Indians, having been appointed Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in 1905 for his Congo work. |

| Movement |

|

| Parents |

|

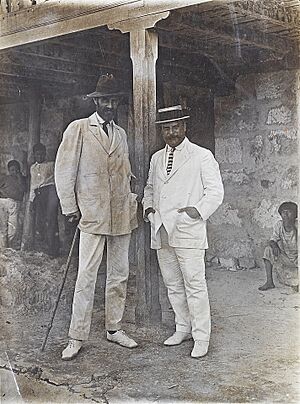

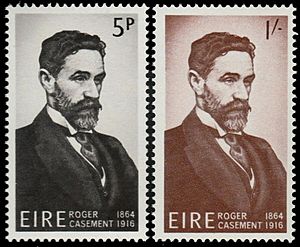

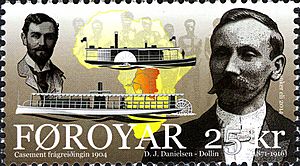

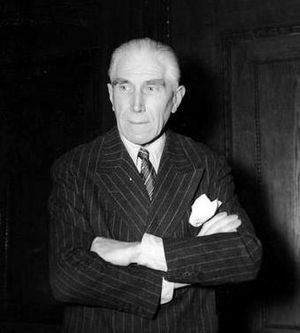

Roger David Casement (Irish: Ruairí Dáithí Mac Easmainn; 1 September 1864 – 3 August 1916) was an important diplomat and Irish nationalist. He was executed by the United Kingdom for acting against the government during World War I.

Casement worked for the British Foreign Office as a diplomat. He became known for helping people and later as a poet and a leader in the Easter Rising. People called him the "father of twentieth-century human rights investigations." He was honored in 1905 for his report on the Congo. In 1911, he was made a knight for his work investigating human rights problems in the rubber industry in Peru.

As a young man in Africa, Casement first worked for businesses. Then he joined the British Colonial Service in 1891 as a British consul. He did this job for over 20 years. He saw how people were treated badly in colonies and began to dislike imperialism. After leaving his job in 1913, he became more involved in Irish independence movements.

During World War I, he tried to get military help from Germany for the 1916 Easter Rising. This uprising aimed to make Ireland independent. He was arrested, found guilty, and executed for acting against the government. He lost his knighthood and other honors.

Early Life & Family Background

Growing Up in Ireland

Roger Casement was born in Dublin, Ireland, into an Anglo-Irish family. He spent his very early childhood in Sandycove.

His father, Captain Roger Casement, was a soldier. His mother, Anne Jephson, was from a Dublin family. When Roger was nine, his mother died. His father then moved the family back to Ireland, to County Antrim. When Roger was 13, his father also died. Roger was then cared for by relatives. He went to school in Ballymena. At 16, he left school and went to England to work for a shipping company called Elder Dempster.

Roger's brother, Thomas Hugh Jephson Casement, had an adventurous life at sea and as a soldier. He later helped start the Irish Coastguard Service.

A British Diplomat & Human Rights Champion

Investigating Abuses in the Congo

Casement worked in the Congo starting in 1884. This area was controlled by King Leopold II of Belgium. Casement helped build a railroad to improve trade. During this time, he learned African languages.

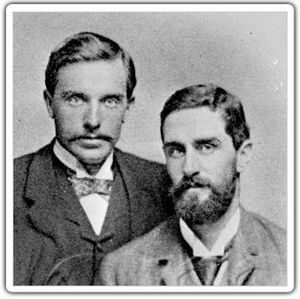

In 1890, Casement met Joseph Conrad, a writer. Both believed that European rule would bring good things to Africa. But they soon saw how wrong they were. Conrad later wrote a book called Heart of Darkness about the problems of colonialism. Casement later showed the world the terrible conditions he found in the Congo.

In 1903, the British government asked Casement to investigate human rights in the Congo Free State. King Leopold II had a private army called the Force Publique. This army used violence to force people to collect rubber and other resources.

Casement traveled for weeks, talking to workers and others. He wrote a long, detailed report in 1904, known as the Casement Report. This report showed the terrible abuses. King Leopold had been using violence and murder to force people to work.

When the report became public, many people were angry. Groups like the Congo Reform Association were formed to demand action. Other countries also spoke out. The Belgian Parliament eventually took control of the Congo from King Leopold in 1908.

Helping People in Peru

In 1906, Casement was sent to Brazil as a consul. He was part of a group investigating slavery by the Peruvian Amazon Company (PAC). This company was based in Britain.

In 1909, a journalist wrote about the abuses by PAC against its workers. Casement traveled to the Putumayo District in the Amazon. He looked into how the local Indians were treated. The company's staff forced Indians into unpaid labor. They were starved, beaten, and sometimes murdered. Casement found conditions as bad as those in the Congo.

He interviewed both the victims and the people who committed the abuses. When his report was made public, there was great anger in Britain. Casement made two long visits to the region.

His report was called a "brilliant piece of journalism." It gave a voice to people in distant colonies. After his report, the company's leaders promised to change. But in 1911, Casement found that they were still using harsh punishments.

Some of the company men who committed killings were charged by Peru. The scandal caused the company to lose a lot of business. Rubber production moved to other parts of the world. The leader of the company, Julio César Arana, was never punished. He later became a senator in Peru.

In 1911, Casement was made a knight for his work helping the Amazonian Indians. He had also received an honor in 1905 for his work in the Congo.

Irish Revolutionary Actions

Returning to Ireland

In 1904, Casement joined the Gaelic League. This group worked to save and bring back the Irish language. He met Irish political leaders to talk about his work in the Congo. He did not support "Home Rule," which was a plan for Ireland to have its own government but still be part of the British Empire. He thought the British Parliament would stop it.

Casement was more impressed by the new Sinn Féin party. This party wanted Ireland to be fully independent. Casement joined Sinn Féin in 1905. He realized that even though he had worked for the British Empire, he was still an Irishman at heart.

Supporting Irish Volunteers

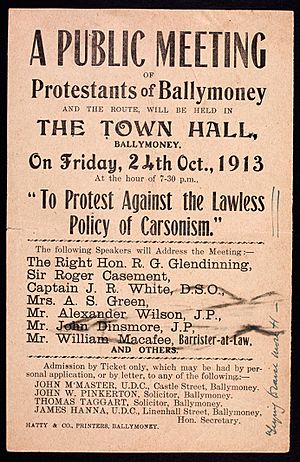

Casement retired from the British consular service in 1913. He then became more involved in Irish nationalist groups. He spoke at meetings, arguing against those who wanted to stay part of the United Kingdom.

In November 1913, Casement joined the Provisional Committee of the Irish Volunteers. This group was formed to protect Irish rights. In April 1914, he saw how a group called the Ulster Volunteers brought German guns into Ireland. Casement believed Irish nationalists needed to do the same.

Seeking German Aid

In July 1914, Casement went to the United States. He wanted to raise money and support for the Irish Volunteers among Irish communities there. He connected with Irish nationalists who had been forced to leave Ireland, especially a group called Clan na Gael.

Some members of Clan na Gael did not fully trust Casement. But others, like Joseph McGarrity, became very loyal to him. Casement helped organize the Howth gun-running in July 1914, where weapons were brought into Ireland. This made his reputation stronger.

In August 1914, when World War I began, Casement and John Devoy met with a German diplomat in New York. They suggested a plan: Germany would sell guns to Irish revolutionaries and provide military leaders. In return, the Irish would revolt against England. This would distract England from its war with Germany.

In October 1914, Casement traveled to Germany. He saw himself as an ambassador for Ireland. While in Norway, someone offered a reward for his capture. In November 1914, Germany declared that it would not invade Ireland to conquer it. Instead, if German troops came to Ireland, they would come as friends.

Casement spent most of his time in Germany trying to create an Irish Brigade. This brigade would be made up of Irish prisoners of war. He wanted them to fight against Britain for Irish independence. However, only 52 out of 2,000 prisoners volunteered. They knew they could be executed as traitors if Britain won the war.

In April 1916, Germany offered the Irish 20,000 rifles and ten machine guns. This was much less than Casement had hoped for. The German weapons never reached Ireland. The British Navy stopped the ship carrying them, the Libau. The ship was disguised as a Norwegian vessel. The captain sank the ship to prevent the British from capturing the weapons.

Arrest and Trial

Casement left Germany in a submarine. He wanted to reach Ireland before the weapons. He hoped to convince the Irish leaders to cancel the rising because German help was not enough.

In the early hours of 21 April 1916, three days before the Easter Rising, the German submarine dropped Casement ashore at Banna Strand in County Kerry. He was ill with malaria. A police sergeant found him at McKenna's Fort and arrested him. He was charged with acting against the government. He tried to send a message to Dublin about the lack of German help.

Casement's trial began on 26 June 1916. The prosecution argued that his actions, even though done in Germany, were still treason. Casement was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged.

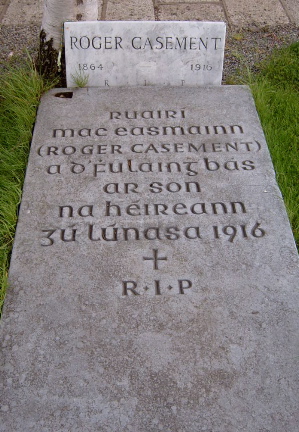

Many people asked for Casement to be pardoned, including writers like Arthur Conan Doyle, W. B. Yeats, and George Bernard Shaw. However, the British government refused. Casement's knighthood was taken away on 29 June 1916. On 3 August 1916, the day he was executed, Casement became a Catholic. He was 51 years old.

Burial and Legacy

Casement's body was buried in the prison cemetery. His last wish was to be buried in Murlough Bay in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. For decades, British governments refused to return his remains to Ireland.

Finally, in 1965, Casement's remains were returned to Ireland. The British government only allowed this if his remains were not brought into Northern Ireland. They feared it would cause problems between Catholics and Protestants.

Casement's body lay in state in Dublin for five days. After a state funeral, he was buried with full military honors in Glasnevin Cemetery in Dublin. He was buried near other Irish republicans. The President of Ireland, Éamon de Valera, who was the last surviving leader of the Easter Rising, attended the ceremony. About 30,000 people were there.

Casement's Legacy

Places and Organizations Named After Him

Many places and groups are named after Roger Casement:

- Casement Park, a sports ground in west Belfast.

- Several Gaelic Athletic Association clubs, like Roger Casements GAA Club in Coventry, England.

- Gaelscoil Mhic Easmainn, an Irish-speaking school in Tralee, County Kerry.

- An estate in Dundalk called Árd Easmuinn, Casement Heights.

- Casement Aerodrome, an Irish Air Corps base near Dublin.

- Casement Rail and Bus Station in Tralee, near where he landed.

- Roger Casement Park, an estate in Cork.

- A street and estate in Clonakilty, County Cork.

- A monument at Banna Strand in Kerry.

- A statue in Ballyheigue, County Kerry.

- A statue in Dún Laoghaire harbor.

- Many streets in Finglas, County Dublin.

- Casement Street in Harryville, Ballymena, County Antrim.

Casement in Books, Plays, and Films

Casement has been featured in many stories since his death:

- The song "Lonely Banna Strand" tells his story.

- Arthur Conan Doyle used Casement as inspiration for a character in his 1912 novel, The Lost World.

- W. B. Yeats wrote a poem, The Ghost of Roger Casement, asking for his remains to be returned.

- Roger Casement is in Giant's Causeway (1922) by Pierre Benoit, shown as a noble hero.

- Agatha Christie mentions Casement in her 1941 novel N or M?

- Brendan Behan wrote about his family's respect for Casement in Borstal Boy (1958).

- The play Prisoner of the Crown (1972) is about him.

- A German TV series, Sir Roger Casement (1968), was made about his time in Germany.

- A radio play by David Rudkin called Cries from Casement as His Bones are Brought to Dublin (1973).

- The Dream of the Celt by Mario Vargas Llosa is a novel based on Casement's life.

- The band ...And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead released a song called "The Betrayal of Roger Casement & the Irish Brigade" (2008).

- Dying for Ireland (2012) is a novel by Alan Lewis about Casement's prison writings.

- A one-act play, Shall Roger Casement Hang?, was performed in 2016.

- The Trial of Roger Casement is a graphic novel by Fionnuala Doran.

- Roger Casement is discussed in W. G. Sebald's novel The Rings of Saturn.

- Valiant Gentlemen (2016) is a novel about Casement's friendship with Herbert Ward.

- Roger Casement – Heart of Darkness (1992) is a documentary by Kenneth Griffith.

- The Ghost of Roger Casement (2002) is a documentary that looks into his private diaries.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Roger Casement para niños

In Spanish: Roger Casement para niños