Irish in the British Armed Forces facts for kids

Irish people in the British Armed Forces talks about the long history of Irish people serving in the British Army, Royal Navy, Royal Air Force, and other parts of the British military. For a long time, from 1800 to 1922, Ireland was part of the United Kingdom. During this period, many Irish men joined the British Army. People from different backgrounds joined for different reasons. Some officers from wealthy Anglo-Irish families wanted to support their "mother country." Others, often poorer Irish Catholics, joined to help their families or to find adventure.

Many Irish people, including those who moved to Britain and people of Ulster-Scots heritage, fought in both World War I and World War II for Britain. However, after Ireland became independent and during a difficult time called The Troubles, joining the British forces became a sensitive topic in Ireland. Even so, Irish citizens still have the right to serve in the British Army today.

History

Early Connections

Irish Fighters with the Normans

Long ago, after the Normans came to Ireland, some Irish fighters called ceithearnach (kerns) worked as paid soldiers for Anglo-Norman lords. They fought in different wars, not just in Ireland but also in England during the Wars of the Roses and in France during the Hundred Years' War. For example, in 1418, the Earl of Ormond brought Irish kerns to fight for King Henry V of England at the Siege of Rouen.

During the Wars of the Roses, when different English families fought for the throne, Ireland was often a safe place for those out of power. They would try to gather an army there. Irish troops fought on both sides in the Battle of Piltown in Ireland in 1462. A famous example is the Battle of Stoke Field in 1487, where the Earl of Lincoln gathered 5,000 Irish kerns to fight for his side.

Tudor Times and Military Role

The Tudor period brought new military changes to Ireland. At first, English rulers like King Henry VIII wanted Irish leaders to join forces with the English Crown. This meant giving up their old customs but keeping their lands. There was no regular army then. Local officials, sometimes Irish or Old English, handled military matters.

Later, under rulers like Queen Elizabeth I, things became tougher. A strict rule called martial law was put in place. This allowed people suspected of opposing the Crown to be executed without a trial. English settlers were also brought in to manage military affairs. Many Irish and Old English leaders lost their power. This led to revolts by people like James FitzMaurice FitzGerald. English massacres, like those at Rathlin and Mullaghmast, made the Irish distrust the Crown even more. This helped create early ideas of Irish nationalism. Eventually, some Irish leaders, like Aodh Ruadh Ó Domhnaill, joined with Catholic Spain to fight against the Protestant Tudor forces.

Stuart Times and Conflicts

During the Stuart period, religious differences became a big problem in Irish society. The English Crown tried to make everyone follow the Church of England. In Ireland, this was even worse because it also meant losing land and being forced to become more English. Irish Catholics wanted more rights, called "The Graces." The situation exploded with the Irish Rebellion of 1641, when Irish Catholic gentry tried to take control. This led to a lot of fighting and violence.

In 1644, during the English Civil War, the English Parliament ordered "no quarter to the Irish" fighting on English soil. This meant Irish prisoners of war could be killed. Some Irish troops from Munster fought for the King, and this rule was sometimes used against them. For example, Irish prisoners were killed at Shrewsbury in 1645.

Modern Army and Regiments

Napoleonic and Victorian Eras

In 1778, some laws against Catholics were changed, allowing them to own land and join the British Army. The British Army needed soldiers for the American Revolutionary War. Many Irish Catholics saw this as a chance for work. It's thought that about 16% of the regular soldiers and 31% of the officers in the British Army during this war were Irish. By 1813, about one-third of the entire British Army was Irish.

After the French Revolution, new conflicts began. The United Irishmen, a group of radical Protestants and Catholics, wanted to create an independent Irish republic with help from France. In 1798, a major rebellion broke out. Despite the fighting, many Irish men, both Catholic and Protestant, joined the British Army and Royal Navy to fight against Napoleon Bonaparte. The Irish-born Duke of Wellington led the British to victory at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Irish regiments like the 27th Inniskilling Regiment were known for their bravery. At the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, about a quarter of the Royal Navy crew were Irish.

During the 19th century, the British Army began to include Irish cultural elements in its uniforms and traditions. Irish soldiers were sometimes seen as "martial races," meaning they were thought to be naturally good at fighting.

World War I and World War II Service

During World War I (1914-1918), Ireland was part of the United Kingdom. Many Irish people, both nationalists and unionists, supported the war effort at first. Over 200,000 men from Ireland fought in the war, and about 30,000 died serving in Irish regiments. After the war, Irish republicans declared independence, leading to the Irish War of Independence (1919-1922). Some Irish ex-soldiers fought on both sides of this conflict.

During World War II (1939-1945), Ireland was officially neutral and independent. However, more than 80,000 Irish-born men and women joined the British armed forces. Between 5,000 and 10,000 of them died during the war.

The Troubles

The Troubles (1969-2006) in Northern Ireland changed the relationship between Irish people and the British Armed Forces. At first, some Irish people in Northern Ireland were happy when the British Army arrived to stop violence. But when the British Army searched homes for weapons, the situation got worse. Groups like the PIRA (Provisional Irish Republican Army) began fighting to force Northern Ireland to leave the United Kingdom and join a United Ireland.

During this time, terrible things happened on all sides. A famous example is Bloody Sunday (1972) in Derry in 1972. Some Scottish regiments were seen as being too close to loyalist groups. For Irish people living in Britain, PIRA bombings in England made some want to show their loyalty to Britain. Others joined groups that wanted the British to leave Northern Ireland.

In 1992, two regiments, the Royal Irish Rangers and the Ulster Defence Regiment, joined to form the Royal Irish Regiment.

Into the 21st Century

Since the Northern Ireland peace process and the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, tensions have greatly reduced. Thousands of Irish people still join the British Armed Forces today. This has even increased since Ireland's economy faced problems in 2008. In 2011, when Queen Elizabeth II visited Ireland, it was a very friendly visit. An Irish major general, David O'Morchoe, showed her and the President of Ireland a memorial garden for Irish soldiers.

In 2000, about 1,000 Irish citizens were serving in the British armed forces. By 2011, recruits from the Republic of Ireland made up about 5% of new British armed forces members each year.

People and Stories

Famous Irish Figures

During World War II, some famous Irish people fought for Britain. These included Donald Garland and Eugene Esmonde from the Royal Air Force, and James Joseph Magennis from the Royal Navy, all of whom won the Victoria Cross for their bravery. Brendan Finucane was a well-known Irish pilot who fought in the Battle of Britain. James Scully from Dublin won a George Cross for his brave actions after the Liverpool Blitz.

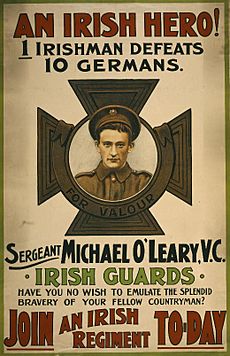

Victoria Cross Winners

Many people born in Ireland have received the Victoria Cross, which is the highest award for bravery in the British Armed Forces. In fact, among all the countries that were part of the British Empire, only England has more winners. Ireland has 190 awards, more than Scotland (158) or Australia (97). If you compare it to the population, Ireland has won a huge number of these awards. The first person to win a Victoria Cross was Charles Davis Lucas from County Armagh, for his actions in 1854.

The large number of Irish Victoria Cross winners was even made fun of in a play by Dublin writer George Bernard Shaw in 1915. His play, O'Flaherty V.C., tells the story of an Irishman from a nationalist family who joins the British Army just for adventure, not for patriotism. He wins a Victoria Cross even though he doesn't care about the war's reasons.

Memorials and Remembering

There are many war memorials in Ireland that remember Irish people who served in the British Armed Forces. Some are old, from Victorian times. Important local memorials include one at Kickham Barracks and a large Gaelic cross for the Royal Munster Fusiliers in Killarney. There are also monuments in churches, especially Anglican ones. Many war memorials in Britain also have Irish surnames on them.

The most important memorial is the Irish National War Memorial Gardens in Dublin. It remembers the 49,400 Irish soldiers who died in World War I. This garden was designed by Edwin Lutyens and finished in 1938, after Ireland became independent. Even though it honors soldiers who fought for Britain, it had support from different political groups in Ireland. There are also memorials in Europe, like the Menin Gate in Belgium, which lists many Irish soldiers' names. The Island of Ireland Peace Park in Belgium and the Ulster Tower in France also remember Irish soldiers.

World War II Veterans

During World War II, Ireland stayed neutral. However, nearly 5,000 members of the Irish Defence Forces left their posts to join the British Armed Forces. When they returned home after the war, the Irish government punished them. They lost their pensions and were banned from public sector jobs for seven years. This punishment was much debated. Some people argued it was too harsh, while others said it was fair for desertion.

In 2011, a group called the 'Irish Soldiers Pardons Campaign' started to get the Irish government to apologize for how these soldiers were treated. In 2013, the Irish Minister for Defence, Alan Shatter, gave a formal apology in the Irish Parliament. The government then passed a law giving these veterans a formal pardon.

Irish Republican Views

Not all Irish nationalists were against Irish people joining the British Armed Forces, especially those who wanted Home Rule (self-government within the British Empire). However, Irish republicanism has always wanted complete independence from Britain. Republicans often saw the British military as an occupying force. They also sometimes tried to get their own members to join the British military to gain fighting experience.

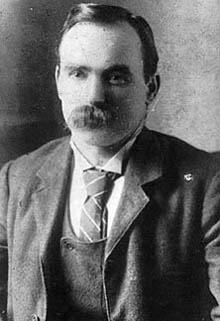

Many men who later became important Irish republican leaders had served in the British Army. These include James Connolly, Tom Barry, and Emmet Dalton. Besides direct opposition, many Irish rebel songs were written to speak out against Irish people joining the British Army or to criticize the British forces in Ireland. Some famous songs include Join the British Army, The Recruiting Sergeant, and Foggy Dew.

Gaelic Games and the Military

The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) was created in the 19th century to promote Irish sports like hurling and Gaelic football. These were seen as Irish alternatives to British sports like rugby and soccer. In 1897, the GAA made a rule, called Rule 21, that banned all members of the British Armed Forces and police from playing Gaelic games. This rule was mainly to stop police from spying on GAA members, who were often nationalist.

Rule 21 stayed in place even after Ireland became independent. During The Troubles, there was a lot of distrust. Some unionists thought parts of the GAA supported the IRA, and the GAA was suspicious of police joining. As part of the peace process, and as the police force changed, there were efforts to lift the ban. In 2001, Rule 21 was finally removed. Today, Irish people serving in the Irish Guards even have their own GAA team in London.

Irish Regiments Today

Towards the end of the 1600s, some regiments began to form that were loyal to British interests. Many of these came from the Williamite War in Ireland. Over time, more regiments with strong Irish ties were created, like the Connaught Rangers and the Irish Guards. Many Irish regiments were disbanded after Ireland gained independence. However, an association called the Combined Irish Regiments Association still exists to remember their history.

Many British regiments today still have Irish traditions. For example, the motto of the Royal Irish Regiment, Faugh A Ballagh, means "Clear the Way!" in the Irish language. Other regiments use Irish symbols like the Irish harp or the shamrock on their badges. They also play Irish marching songs and celebrate St Patrick's Day on March 17th. The Royal Irish and Irish Guards even have an Irish Wolfhound as their mascot, named "Brian Boru IX" and "Domhnall."

| Regiment | Active | History and Details |

|---|---|---|

| Royal Irish Regiment | 1689–present | This regiment was formed by joining the Royal Irish Rangers and the Ulster Defence Regiment. It also includes the history of older regiments like the Royal Irish Rifles and Royal Irish Fusiliers. |

| Irish Guards | 1900–present | Part of the Guards Division, this regiment was created by Queen Victoria to honor Irish soldiers who fought in the Second Boer War. They are sometimes called the Fighting Micks and wear bearskins and redcoats for ceremonies. |

| Queen's Royal Hussars | 1685–present | This cavalry regiment has Irish roots from the 8th King's Royal Irish Hussars. They are famous for their part in the Charge of the Light Brigade. |

| Royal Dragoon Guards | 1685–present | This cavalry regiment comes from several Irish-based regiments, including the 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards. Today, they have both a Yorkshire and Irish identity. |

| Royal Lancers | 1689–present | This cavalry regiment includes the history of the 5th Royal Irish Lancers. Its four current squadrons are named after its older regiments. |

| Scottish and North Irish Yeomanry | 1902–present | This regiment started as the North Irish Horse cavalry. Today, a part of it is based in Belfast and Coleraine. |

| London Irish Rifles | 1859–present | This regiment was formed to represent Irish people living in London. Today, it is part of the London Regiment. |

| Liverpool Irish | 1860–present | This regiment was formed for Irish people in Liverpool. Today, it is part of a Royal Artillery unit. |

Images for kids

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |