Tom Kettle facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Tom Kettle

|

|

|---|---|

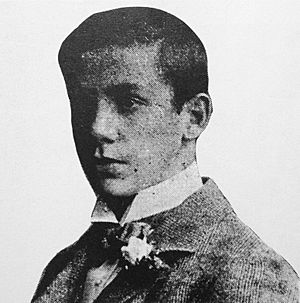

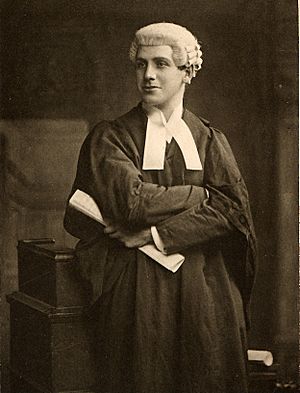

Thomas Kettle BL. in 1905

|

|

| Member of Parliament for East Tyrone |

|

| In office 5 July 1906 – 28 November 1910 |

|

| Preceded by | Patrick Doogan |

| Succeeded by | William Redmond |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Thomas Michael Kettle

9 February 1880 Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 9 September 1916 (aged 36) near Ginchy, France |

| Political party | Irish Parliamentary Party |

| Spouse |

Mary Sheehy

(m. 1909) |

| Alma mater | University College Dublin |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | British Army |

| Years of service | 1914–1916 |

| Rank | Lieutenant |

| Unit | Royal Dublin Fusiliers |

| Battles/wars | First World War |

Thomas Michael Kettle (born February 9, 1880 – died September 9, 1916) was a talented Irish writer, journalist, and politician. He was also a soldier and a poet. As a member of the Irish Parliamentary Party, he served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for East Tyrone from 1906 to 1910. This meant he helped make laws in the British Parliament.

He joined the Irish Volunteers in 1913. When World War I started in 1914, he joined the British Army. He was sadly killed in action on the Western Front in 1916. Thomas Kettle was admired by many, including the famous writer James Joyce, who thought of him as a close friend. He was known for his sharp mind and great speaking skills. Many believed his death was a big loss for Ireland.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Thomas Kettle was born in Malahide or Artane, Dublin, Ireland. He was the seventh of twelve children. His father, Andrew Kettle, was a well-known Irish nationalist politician and farmer. Andrew Kettle helped start the Irish Land League.

Thomas's father greatly influenced his political ideas. Andrew Kettle was involved in the movement to get "Home Rule" for Ireland. Home Rule meant Ireland would have more control over its own government, rather than being fully ruled by Britain.

School Days

Thomas and his brothers went to the Christian Brothers' O'Connell School in Dublin. He was a very good student there. In 1894, he went to Clongowes Wood College in County Kildare. He was known for being witty and a strong debater. He enjoyed sports like athletics, cricket, and cycling. He also did very well in English and French.

University Life

In 1897, Thomas started at University College Dublin. He was seen as a very popular and inspiring student. He quickly became a leading student politician and a brilliant scholar. He was elected to a top position at the Literary and Historical Society. His friends at university included future important figures like James Joyce.

Thomas Kettle took a break from his studies in 1900 due to illness. He traveled in Europe to feel better and improve his German and French. He returned to Dublin and finished his studies in 1902, earning a degree in mental and moral science.

Journalism and Politics

After university, Thomas Kettle studied law and became a barrister (a type of lawyer) in 1905. However, he spent most of his time on political journalism. He stayed connected with University College, debating and editing the college newspaper.

He strongly supported the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), which wanted Home Rule for Ireland. He helped start a youth branch of the United Irish League in 1904 and became its president. This caught the attention of the Irish Party leader, John Redmond.

Kettle was offered a chance to become a Member of Parliament, but he chose to edit a newspaper called The Nationist. This paper supported the Irish Party but also shared Kettle's liberal views on topics like education and women's rights. He left the paper in 1905 after a disagreement about an article.

Becoming an MP

In 1906, after the death of the MP for East Tyrone, Thomas Kettle decided to run for the seat. He won by a small number of votes. This made him one of the few young people to join the Irish Party in the House of Commons in London.

He was seen as a future leader of the party. In Parliament, he was known as a funny and sharp speaker. He strongly supported the Irish Party's goal of achieving Home Rule peacefully. He also spoke about better education for Catholics in Ireland and Ireland's economy.

Thomas Kettle loved European culture. He believed Ireland should be connected with the rest of Europe. He once wrote: "My only programme for Ireland consists in equal parts of Home Rule and the Ten Commandments. My only counsel to Ireland is, that to become deeply Irish, she must become European."

Academic and Family Life

In 1908, he became the first Professor of National Economics at University College Dublin. He was a popular professor, but it was hard for him to balance his teaching with his work as an MP. He published several works on economic issues.

In September 1909, he married Mary Sheehy. She was also a university graduate and came from a well-known nationalist family. Her father, David Sheehy, was also an MP. Thomas and Mary Kettle had one daughter, Elisabeth, born in 1913.

Kettle won his East Tyrone seat again in the January 1910 election. However, he did not run in the second election that December. Even out of Parliament, he continued to support the Irish Party and Home Rule. He was very happy when the 1912 Home Rule Bill was introduced.

The Road to War

During the 1913 Dublin strike and lockout, Thomas Kettle supported the workers. He wrote articles that showed the terrible living and working conditions of Dublin's poor. He also helped try to find a peaceful solution between workers and employers.

In 1913, Kettle also joined the Irish Volunteers. This was a new Irish Nationalist group formed to respond to the Ulster Volunteers in the north. The Ulster Volunteers were against Home Rule for all of Ireland.

In July 1914, Kettle traveled to Belgium for the Irish Volunteers to buy weapons. While he was there, World War I broke out. He became a war reporter for the Daily News. He reported on the German army's movements. He saw how the Imperial German Army treated Belgian civilians. This made him believe that Germany was a threat to Europe's freedom. He described the conflict as "A war of Civilization vs Barbarianism."

World War I Service

When World War I began, Thomas Kettle returned to Dublin. He supported John Redmond's view that Irishmen should join the British Army to fight in the war. Redmond believed that if Ireland helped Britain, Home Rule would be granted after the war.

Kettle tried to join the 7th Battalion of the Leinster Regiment but was refused due to his health. He then received a commission as a Lieutenant in the British Army, but was limited to service at home.

He continued to argue that Irishmen had a duty to join the allied forces against Germany. By 1916, Kettle had published many books, articles, poems, and essays. Despite feeling sad about the war's growing destruction, he kept asking to be sent to the Western Front.

His health improved, and he finally received a commission into the 9th Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers. He went to France in early 1916. The harsh conditions in the trenches made him ill again, and he returned to Dublin on sick leave. He saw the damage to Dublin from the Easter Rising (a rebellion against British rule). He refused offers for a permanent staff job and returned to his battalion.

Before leaving Ireland on July 14, 1916, he predicted that the Easter Rising rebels would be seen as heroes in the future. He felt that their actions harmed the peaceful path to Irish self-government. Kettle believed he was fighting for European civilization. He wrote: "Used with the wisdom that is sown in tears and blood, this tragedy of Europe may be and must be the prologue to the two reconciliations of which all statesmen have dreamed, the reconciliation of Protestant Ulster with Ireland, and the reconciliation of Ireland with Great Britain."

In a letter to his friend Joseph Devlin shortly before his death, Kettle wrote: "I hope to come back. If not, I believe that to sleep here in the France that I have loved is no harsh fate, and that so passing out into silence, I shall help towards the Irish settlement. Give my love to my colleagues – the Irish people have no need of it."

Death and Legacy

Thomas Kettle was killed in action on September 9, 1916. He was fighting with the 9th Battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers near the village of Ginchy during the Battle of the Somme. He was 36 years old. His body was buried by the Welsh Guards, but the grave was later lost. His name is carved on the Thiepval Memorial in France, which remembers soldiers missing from the Somme.

The poet George William Russell wrote about Kettle, comparing his sacrifice to those who led the 1916 Easter Rising: "You proved by death as true as they,

In mightier conflicts played your part,

Equal your sacrifice may weigh

Dear Kettle of the generous heart."

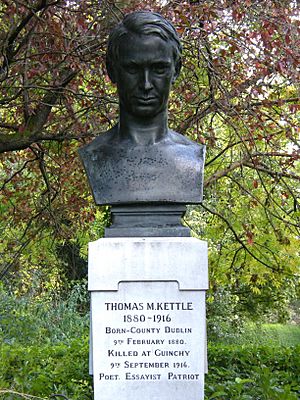

Memorials

A bronze statue (bust) of Thomas Kettle was made in Dublin in 1921. It took almost twenty years to be put up because of disagreements after Ireland became independent. The authorities were not keen on honoring Irishmen who fought in World War I. It was finally placed in St. Stephen's Green in 1937 without a ceremony.

- A stone tablet remembers him in the Island of Ireland Peace Park in Messines, Belgium.

- His name is on a bronze plaque in the Four Courts in Dublin. This plaque remembers 26 Irish lawyers who died in the Great War.

- Kettle is also remembered on the Parliamentary War Memorial in Westminster Hall in London. This memorial lists 22 Members of Parliament who died in World War I.

- In 1932, a special book of remembrance was unveiled for the House of Commons. It includes a short story about Thomas Kettle's life and death.

The Literary and Historical Society (University College Dublin) holds a yearly ceremony at his bust in St. Stephen's Green. The UCD Economics Society also has an award named after him.

A French newspaper, L'Opinion, wrote a tribute to him after his death: "All parties bowed in sorrow over his grave... He was more. He was Ireland! He had fought for all the aspirations of his race... He died, a hero in the uniform of a British soldier, because he knew that the faults of a period or of a man should not prevail against the cause of right or liberty."

Poetry

Kettle's most famous poem is a sonnet called "To My Daughter Betty, the Gift of God." He wrote it just days before he died. The last lines explain that he and other Irish soldiers "Died not for flag, nor King, nor Emperor/But for a dream, born in a herdsman's shed/and for the secret Scripture of the poor."

Images for kids

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |