Dublin lock-out facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Dublin lock-out |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

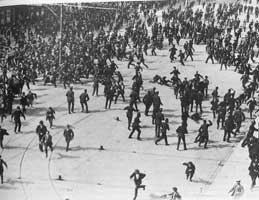

Dublin Metropolitan Police break up a union rally

|

|||

| Date | 26 August 1913 – 18 January 1914 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by |

|

||

| Goals |

|

||

| Methods | Strikes, rallies, walkouts | ||

| Resulted in |

|

||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

|

|||

| Lead figures | |||

|

|

|||

| Number | |||

|

|||

| Casualties | |||

|

|||

| 2 dead, several hundred injured | |||

The Dublin Lock-out was a huge fight between workers and employers in Dublin, Ireland. It happened from August 1913 to January 1914. About 20,000 workers and 300 employers were involved. This event is seen as the most important and difficult worker dispute in Irish history. The main reason for the fight was the workers' right to join a union.

Contents

Why the Lock-out Happened

Life in Dublin for Workers

Many workers in Dublin lived in very poor conditions. They often lived in crowded tenement buildings. For example, many families would share a single house. Diseases like tuberculosis (TB) spread easily in these crowded areas. A report in 1912 showed that TB deaths in Ireland were much higher than in England or Scotland. Most of these deaths were among the poor.

It was hard for unskilled workers to find steady jobs. They often had to compete with each other for work every day. The job usually went to the person who would work for the lowest pay. Before unions, these workers had no one to speak up for them.

James Larkin and the ITGWU

James Larkin was a key leader for the workers. He was a docker (someone who loads and unloads ships) from Liverpool. In 1907, he helped organize a strike for dock and transport workers in Belfast. Larkin started using a new tactic called the sympathetic strike. This is when workers who are not directly involved in a dispute go on strike to support other striking workers.

Larkin's methods were new and caused some trouble. He later left the British union he was with. In 1909, he started an Irish union called the Irish Transport and General Workers' Union (ITGWU). This was the first Irish union for both skilled and unskilled workers.

The ITGWU quickly became popular. It grew from 4,000 members in 1911 to 10,000 by 1913. This worried the employers. Larkin believed in using strong unions and big strikes to make society fairer for workers.

Larkin, Connolly, and the Labour Party

James Connolly was another important leader for the workers. He was a great speaker and writer. Connolly spoke often about socialism and Irish nationalism. In 1911, he became an organizer for the ITGWU in Belfast.

In 1912, Connolly and Larkin started the Irish Labour Party. They wanted to represent workers in the British Parliament. This was important because Ireland was discussing Home Rule, which meant having its own government.

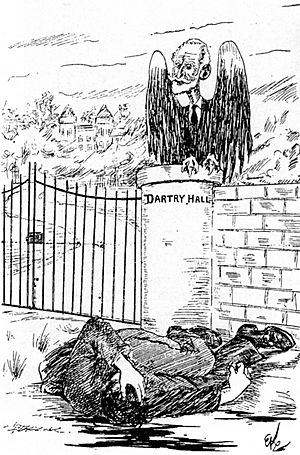

William Martin Murphy and the Employers

William Martin Murphy was one of Ireland's most powerful businessmen. He owned many companies, including the Dublin United Tramway Company, a department store, and several newspapers. He was also a former Member of Parliament.

Murphy's workers often had very long hours, sometimes up to 17 hours a day. They also had strict rules and low pay compared to workers in other cities. Murphy was not against all unions, but he strongly disliked the ITGWU and its leader, Larkin. He saw Larkin as a dangerous revolutionary.

In July 1913, Murphy met with 300 other employers. They all agreed to stop the ITGWU from organizing their workers. On August 15, Murphy fired 40 workers he thought were ITGWU members. Over the next week, he fired another 300. This started the big dispute.

The Dispute Begins

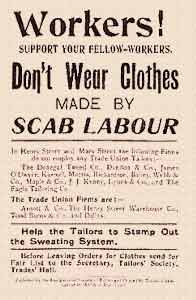

The fight between workers and employers became very serious. Employers in Dublin refused to let their workers come to work. This was called a "lock-out." They also hired new workers, called "strike-breakers," from Britain and other parts of Ireland.

Dublin's workers were very poor, but they received help. British unions and other groups in Ireland sent money to support them. The ITGWU made sure the money was given out fairly.

There was a plan to send the children of starving Irish strikers to stay with British union families. However, the Roman Catholic Church and other groups stopped this. They worried that Catholic children would be influenced by Protestants or atheists in Britain. The Church generally supported the employers during the lock-out.

Interestingly, Guinness, the biggest employer in Dublin, did not join the lock-out. They had a policy against sympathetic strikes. They did, however, send money to the employers' fund.

Violence and the Irish Citizen Army

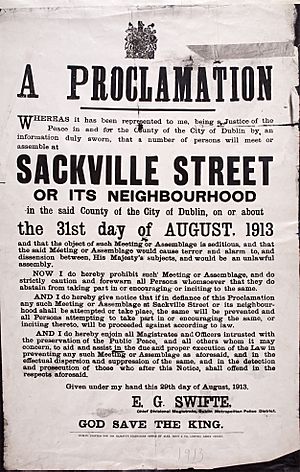

Strikers tried to stop strike-breakers from working. Sometimes, there was violence on both sides. The Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) often used force against workers. On August 31, 1913, the police attacked a meeting on Sackville Street (now O'Connell Street). This meeting had been banned. Two workers, James Nolan and John Byrne, died, and over 300 were hurt.

This attack happened after James Larkin appeared to speak at the banned meeting. He had been secretly brought into William Martin Murphy's Imperial Hotel and spoke from a balcony. This event is often called Bloody Sunday. Later, another worker, Alice Brady, was shot and killed by a strike-breaker.

To protect workers during demonstrations, Connolly, Larkin, and a former British Army Captain named Jack White formed a group called the Irish Citizen Army.

The lock-out lasted for seven months. It affected thousands of families in Dublin. William Martin Murphy's newspapers often showed Larkin as the bad guy. But other important people, like Patrick Pearse and William Butler Yeats, supported the workers.

How the Lock-out Ended

The lock-out ended in early 1914. The British unions decided not to support a bigger strike. Many workers were very hungry and had to go back to work. They often had to promise not to join the ITGWU.

The ITGWU was badly hurt by this defeat. It was also affected when Larkin left for the United States in 1914. Later, James Connolly was executed in 1916 after the Easter Rising.

However, the union was rebuilt by William O'Brien and Thomas Johnson. By 1919, the ITGWU had even more members than it did before the lock-out.

Many workers who were fired or "blacklisted" (meaning no one would hire them) joined the British Army. They needed money to support their families. Many of them ended up fighting in World War I.

Even though the workers didn't get much better pay or conditions right away, the lock-out was a turning point in Irish labor history. It showed that workers could stand together and fight for their rights. After this, no employer would try to completely "break" a union like Murphy had tried to do. The lock-out also hurt many businesses in Dublin, causing some to go bankrupt.

See also

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |