Kilmainham Gaol facts for kids

| Príosún Chill Mhaighneann | |

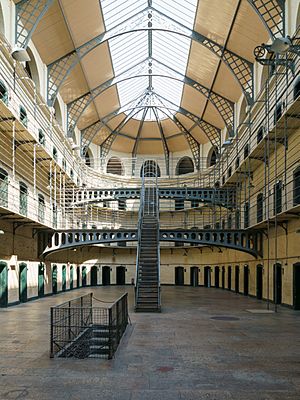

Main Hall

|

|

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

| Location | Kilmainham, Dublin, Ireland |

|---|---|

| Type | Prison museum |

| Owner | Office of Public Works |

| Public transit access | Heuston railway station Suir Road Luas stop (Red Line) |

| Official name | Kilmainham Gaol |

| Reference no. | 675 |

Kilmainham Gaol (which means Príosún Chill Mhaighneann in Irish) is a famous old prison in Kilmainham, Dublin, Ireland. It is now a popular museum run by the Office of Public Works, a part of the Irish government. Many important Irish revolutionaries were held and executed here, especially the leaders of the 1916 Easter Rising. These included Patrick Pearse, James Connolly, and Constance Markievicz. The prison played a big role in Ireland's fight for independence.

Contents

History of Kilmainham Gaol

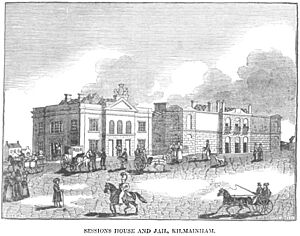

When it was first built in 1796, Kilmainham Gaol was called the "New Gaol." This was to show it was different from an older, less pleasant prison nearby. Its official name was the County of Dublin Gaol. It was managed by a group called the Grand Jury for County Dublin.

Prison Life and Conditions

In the early days, public hangings sometimes happened outside the prison. However, after the 1820s, very few hangings took place there. A small room for hangings was added inside the prison in 1891.

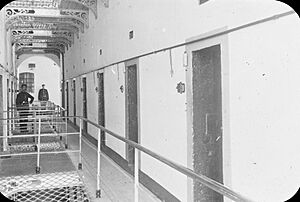

Life inside the prison was very tough. There was no separation between different types of prisoners. Men, women, and even children were often kept together, sometimes up to five people in one cell. Each cell was about 28 square metres. Prisoners had only one candle for light and warmth, and it had to last for two weeks. This meant most of their time was spent in the cold and dark.

Children were sometimes arrested for small crimes like stealing. The youngest child recorded was said to be only three years old. Many adult prisoners were sent far away to Australia as a punishment.

Improvements and Challenges

The poor conditions for women prisoners led to some changes. In 1809, an inspector noted that male prisoners had iron beds, but women slept on straw on the cold floor. Fifty years later, things hadn't improved much. The women's section, in the west wing, was very crowded. To help with this, 30 new cells for women were added in 1840.

These improvements came just before the Great Famine. During this terrible time, Kilmainham Gaol became extremely overcrowded with many more prisoners.

Later, during the 1923 Irish hunger strikes, Kilmainham was the scene of several hunger strikes. In March 1923, 97 women prisoners went on hunger strike because their privileges were taken away. The strike ended later that month when their privileges were given back. Sadly, Annie (Nan) Hogan, a member of Cumann na mBan, died at age 24 after being released from prison. She was very weak from taking part in hunger strikes at Kilmainham and other jails.

Kilmainham Gaol After Independence

After Ireland became independent, the Kilmainham Gaol closed as a prison in 1924. At first, people saw it as a place of sadness and unfairness. There wasn't much interest in keeping it as a monument to Ireland's fight for freedom. This was also complicated because the first four Republican prisoners executed by the new Irish government during the Irish Civil War were shot in the prison yard.

Plans for Preservation

The Irish government thought about reopening it as a prison in the 1920s, but these plans were dropped by 1929. In 1936, they even considered tearing it down, but it was too expensive.

Interest in preserving the site grew from the late 1930s. The National Graves Association, a group that wanted to remember Irish heroes, suggested turning it into a museum and memorial for the 1916 Easter Rising. This idea was supported by the Commissioners of Public Works. They even discussed moving items from the National Museum of Ireland to a new museum at Kilmainham. However, the Department of Education didn't think it was a good place for a museum. The plans were put on hold during World War II.

After the war, a survey showed the prison was falling apart. With no clear purpose and the Department of Education still not keen on a museum, there was a suggestion to save only the most important parts and demolish the rest. But this didn't happen.

In 1953, the government again considered the National Graves Association's idea to restore the prison and create a museum. This was part of a plan to create jobs. However, no progress was made, and the prison continued to decay.

Restoring Kilmainham Gaol

In the late 1950s, ordinary people started a movement to save Kilmainham Gaol. When they heard that the government might demolish the building, a young engineer named Lorcan C.G. Leonard and other people who cared about Irish history formed the Kilmainham Gaol Restoration Society in 1958. They decided to focus on the idea of a united national struggle to avoid arguments about the Civil War.

The society came up with a plan to restore the prison and build a museum using volunteers and donated materials. This idea gained support from trade unions and possibly Dublin Corporation. The Irish government was also under pressure to save the site. So, when the society presented their plan in late 1958, the government liked it because it wouldn't cost them much money.

The Restoration Project

In February 1960, the society's detailed plan was approved. This plan also included making the site a tourist attraction. In May 1960, the prison keys were officially given to a board of trustees. This board had five members from the society and two from the government. They paid a very small rent for five years, hoping the restored prison would then be permanently theirs.

Work began in May 1960 with sixty volunteers. They cleared away overgrown plants, fallen stones, and bird droppings. By 1962, the important prison yard, where the 1916 Rising leaders were executed, was cleared. The Victorian part of the prison was almost finished. Kilmainham Gaol officially opened to the public on April 10, 1966. The full restoration was completed in 1971 when the prison chapel was reopened. The Magill family, especially Joe Magill, worked as caretakers and helped with the restoration from the very beginning.

Today, Kilmainham Gaol is a museum about Irish nationalism. It offers guided tours of the building. An art gallery on the top floor displays art made by prisoners in modern Irish prisons. It is one of the largest empty prisons in Europe.

In 2013, the Kilmainham courthouse next to the prison, which had been used until 2008, was given to the Office of Public Works. It was renovated as part of a bigger plan to improve the Gaol and the surrounding area before the 100th anniversary of the 1916 Rising. The courthouse opened in 2015 as the new visitor's centre for the Gaol.

Important Events at Kilmainham Gaol

Kilmainham Gaol held prisoners during the Irish War of Independence (1919–21) and many of the anti-treaty forces during the Irish Civil War. Charles Stewart Parnell, a famous Irish political leader, was imprisoned here in 1881-82 with many of his fellow politicians. This was when he signed the Kilmainham Treaty with British Prime Minister William Gladstone.

Famous Prisoners of Kilmainham Gaol

Many well-known figures in Irish history were held at Kilmainham Gaol, including:

- Henry Joy McCracken, 1796

- Robert Emmet, 1803

- Anne Devlin, 1803

- William Smith O'Brien, 1848

- Thomas Francis Meagher, 1848

- Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa, 1867

- Charles Stewart Parnell, 1881

- John Dillon, 1882

- Patrick Pearse, 1916

- Willie Pearse, 1916 (Patrick Pearse's younger brother)

- James Connolly, 1916 (Executed, but not held, at Kilmainham)

- Conn Colbert, 1916

- Constance Markievicz, 1916

- Éamon de Valera, 1916 and 1923

- John MacBride, 1916

- Joseph Plunkett, 1916

- Michael O'Hanrahan, 1916

- Edward Daly, 1916

- Seán Mac Diarmada, 1916

- Grace Gifford, 1922 (wife of Joseph Plunkett)

- Ernie O'Malley, during the War of Independence and the Civil War

- Thomas MacDonagh, 1916

- Thomas Clarke, 1916

- Madeleine ffrench-Mullen, 1916

Films and Music at the Gaol

Kilmainham Gaol's unique look has made it a popular location for filming movies and music videos. Some of the films shot here include:

- The Quare Fellow, 1962

- The Italian Job, 1969

- In the Name of the Father, 1993

- Michael Collins, 1996

- The Wind That Shakes the Barley, 2006

- Paddington 2, 2017 (for its interior scenes)

The Irish band U2 filmed their music video for "A Celebration" at Kilmainham Gaol in July 1982. Another Irish band, Fontaines D.C., performed a live show there on June 14, 2020. The prison was also used in TV series like Into the Badlands, Ripper Street, and Primeval.

Images for kids

-

The cell door of Robert Emmet.

-

A cross marking the place of execution for James Connolly.

See also

In Spanish: Kilmainham Gaol para niños

In Spanish: Kilmainham Gaol para niños

- Prisons in Ireland

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |