Tom Clarke (Irish republican) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas James Clarke

Tomás Séamus Ó Cléirigh |

|

|---|---|

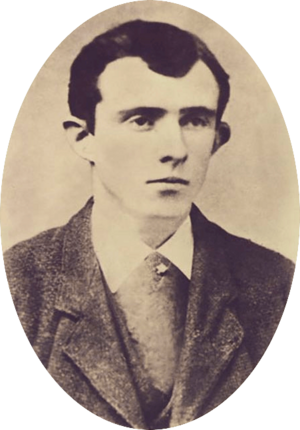

Clarke in 1910

|

|

| Born | 11 March 1858 Hurst Castle, Milford-on-Sea, Hampshire, England

|

| Died | 3 May 1916 (aged 58) Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin, Ireland

|

| Nationality |

|

| Other names | Henry Wilson |

| Organization | Irish Republican Brotherhood |

| Movement | Irish republicanism |

| Spouse(s) | Kathleen Clarke |

| Children | 3 |

Thomas James Clarke (Irish: Tomás Séamus Ó Cléirigh; 11 March 1858 – 3 May 1916) was an Irish republican leader. He was a key figure in the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), a secret group that wanted Ireland to be free from British rule. Many people believe Clarke was the most important person behind the 1916 Easter Rising. He spent most of his life fighting for Irish independence, including 15 years in British prisons. After the Easter Rising failed, he was executed by a firing squad.

Contents

Early Life and Irish Roots

Thomas Clarke was born in England, near Milford-on-Sea, in 1858. His parents, Mary Palmer and James Clarke, were Irish. His father was a sergeant in the British Army. In 1865, when Tom was seven, his family moved to Dungannon, County Tyrone, in Ireland. This is where Tom grew up.

Joining the Irish Republican Brotherhood

When he was 20, in 1878, Tom Clarke joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). This group worked to make Ireland an independent country. By 1880, he was in charge of the local IRB group in Dungannon.

One day, after a police officer shot a man during a riot, Clarke and other IRB members tried to fight some police officers. They had to retreat, and Clarke worried he would be arrested. So, he moved to the United States.

Years in Prison for Irish Freedom

In 1883, Clarke went to London to take part in a plan to use explosives to fight British rule. British police were already watching people involved in this plan. Clarke was arrested with explosives and sentenced to prison for life. He spent 15 years in different British prisons.

By 1896, he was one of only five Irish political prisoners left in British jails. Many people in Ireland held meetings to ask for their release. A politician named John Redmond spoke about Clarke, saying he was a brave man who kept his spirit strong even in prison.

Moving to America and Starting a Family

After being released from prison in 1898, Clarke returned to Ireland. He was welcomed as a hero in Dublin and Dungannon. He stayed with the family of John Daly, a fellow Irish republican who had also been in prison. There, Clarke met John's niece, Kathleen Daly. Tom and Kathleen later fell in love.

Clarke found it hard to find a job in Ireland after his release. So, in 1900, he moved to Brooklyn, in the United States. In 1901, he married Kathleen, who was 21 years younger than him. Another Irish nationalist, John MacBride, was his best man.

In New York, Clarke worked for an Irish nationalist group called Clan na Gael. He also helped start their newspaper, The Gaelic American. In 1905, Clarke became an American citizen. Later that year, he became unwell and moved with Kathleen to a farm in Manorville, New York.

Returning to Ireland and Political Work

Clarke felt he needed to be in Ireland to continue his work for independence. In 1907, he moved back to Dublin and opened a tobacco shop. He quickly became very involved in the IRB again. The IRB was growing stronger with new, younger members like Bulmer Hobson and Seán Mac Diarmada. Clarke became close friends with Hobson and Mac Diarmada, mentoring them.

Because of his strong beliefs and long history, Clarke quickly became a leader in the IRB. He was made treasurer and joined the Supreme Council, which was the main leadership group. In 1910, Clarke, Hobson, and Mac Diarmada started a republican newspaper called Irish Freedom.

Clarke also helped create a group called the Wolfe Tone Clubs Committee. This allowed IRB members to meet without openly saying they were part of the secret IRB. In 1911, Clarke organized a gathering of Irish republicans at the grave of Wolfe Tone to protest a visit by the British King, George V, to Dublin.

Clarke also joined the Gaelic League and Sinn Féin. He joined these groups hoping to influence them from the inside and push them towards full Irish independence. He believed Sinn Féin, which at the time wanted "home rule" (some control over Ireland but still under British rule), did not go far enough. He was not interested in becoming a politician himself.

Clarke supported workers during the 1913 Dublin Lockout, a big strike. He refused to sell newspapers owned by a boss who was against the workers. He also helped collect money for the striking workers.

Clarke also supported equal opportunities for women. He made sure this idea was included in the 1916 Proclamation, a very important document for the Easter Rising.

In 1913, Clarke invited a young speaker named Paidraig Pearse to give a speech at a republican gathering. By November of that year, Clarke brought Pearse into the IRB.

The Irish Volunteers

When the Irish Volunteers were formed in 1913, Clarke did not join publicly. He was a well-known Irish nationalist who had been in prison, and he didn't want his past to make the Volunteers look bad. However, many other IRB members, like Mac Diarmada, Hobson, Pearse, and Éamonn Ceannt, took important roles in the Volunteers. This meant the IRB had a lot of control over the group.

Later, the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, John Redmond, demanded that his party members be added to the Volunteers' leadership. This would give Redmond's supporters more control. Clarke and other strong republicans were against this, but it happened anyway. Clarke never forgave Hobson for supporting Redmond's demand, calling it a "treasonous act."

In September 1914, after World War I began, Clarke and Mac Diarmada led a change within the Irish Volunteers. They took control of the Volunteers' headquarters in Dublin and rejected Redmond's leadership. This caused the Volunteers to split. Most members sided with Redmond and became the National Volunteers, who joined the British army in the war. Those who opposed Redmond kept the name "Irish Volunteers" and stayed in Ireland. Clarke was very happy about this, as it meant the Irish Volunteers were now fully under IRB control. He saw this as a chance to plan a fight for independence.

Planning the Uprising

Clarke and Mac Diarmada became very close after the split with Hobson. As secretary and treasurer, they practically ran the IRB. In 1915, Clarke and Mac Diarmada created the Military Committee of the IRB to plan what would become the Easter Rising. Pearse, Ceannt, and Joseph Plunkett were members, and Clarke and Mac Diarmada joined them soon after.

When an old Irish republican, Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa, died in 1915, Clarke used his funeral to inspire the Volunteers. Pearse gave a famous speech at the graveside, which helped build excitement for action.

In late 1915, Clarke used his connections in New York to arrange for weapons from Germany to be sent to Ireland for the planned uprising. Clarke was very focused on planning every detail of the rising. He wanted to avoid the mistakes of the 1867 Fenian Rising, which had failed due to poor planning. In January 1916, Clarke was accidentally shot in the arm and could no longer use it properly.

Also in January 1916, the IRB made an agreement with James Connolly, a socialist leader, and his Irish Citizen Army. Connolly was added to the IRB Military Committee, and Thomas MacDonagh joined in April. These seven men later signed the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, with Clarke as the first signatory. The IRB worried that Connolly's smaller group might start their own uprising too soon. So, they decided to include Connolly and his group in their plans.

British police in Dublin knew that Clarke was the main person planning a revolution. They watched his tobacco shop very closely and even rented a shop across the street to observe him. They were planning to arrest him just days before the Easter Rising began in April 1916.

In one of the last meetings before the Easter Rising, the military council decided that Tom Clarke's signature should be first on the Proclamation. They felt he had done more than anyone else to make the rising happen.

The Easter Rising

The Easter Rising began with some confusion. Eoin MacNeill, who was supposed to be in charge of the Irish Volunteers, told them not to gather. Clarke was furious and called MacNeill a traitor, but he decided to go ahead with the rising anyway.

During Easter Week, Clarke was at the main headquarters in the General Post Office (GPO) in Dublin. Even though he didn't have a military rank, the fighters saw him as one of the commanders. He was active throughout the week. After Connolly was badly hurt on April 27, Clarke took an active role in leading the fighters.

It is said that Clarke could have been named President and Commander-in-chief, but he refused any military titles. These honors went to Pearse, who was more famous. Kathleen Clarke later said that her husband, not Pearse, was the first president of the Irish Republic.

Late in the week, the GPO had to be evacuated because of a fire. The leaders met in a house on Moore Street to decide what to do. Clarke was the only leader who wanted to keep fighting. But the others voted almost unanimously to surrender. Pearse ordered the rebels to surrender on April 29. Clarke was very upset and cried. He wrote on the wall of the house, "We had to evacuate the GPO. The boys put up a grand fight, and that fight will save the soul of Ireland."

Execution

Clarke was arrested by the British after the surrender. He and the other leaders were taken to a hospital where he was searched in front of other prisoners. Clarke was very distressed when the police showed him a detailed file of his life, including his time in prison and his activities for the IRB. He was later held in Kilmainham Gaol and put on trial on May 2, 1916. Clarke did not speak in his own defense.

Clarke was executed by a firing squad on May 3, 1916, along with Pearse and MacDonagh. Before his execution, he spoke with his wife Kathleen. He told her he was glad to be executed because he dreaded the thought of going back to prison.

Legacy

Historian James Quinn has said that Clarke was "probably the most single-minded of all the 1916 leaders." Even though he looked frail and didn't like public speaking, Clarke was described as the fiercest and most determined of all the Easter Rising leaders.

After her husband's death, Kathleen Clarke became a politician herself. She spoke out against the treaty that ended the Irish War of Independence.

Many places and things are named after Thomas Clarke:

- The Thomas Clarke Tower, a block of flats in Ballymun Flats, was named after him.

- Dundalk railway station was renamed Clarke in 1966 to remember his role in the 1916 Rising.

- The Tom Clarke Bridge crosses the River Liffey in Dublin.

- He was featured on postage stamps in 1966.

- The GAA team in his hometown, Dungannon Thomas Clarkes, is named after him.

- Clarke Square in Collins Barracks is also named in his honor.

Images for kids

Works

- Glimpses of an Irish Felon's Prison Life (1922: The National Publications Committee, Cork)

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |