Wolfe Tone facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Theobald Wolfe Tone

|

|

|---|---|

Portrait in the National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin

|

|

| Born | 20 June 1763 |

| Died | 19 November 1798 (aged 35) Dublin, Kingdom of Ireland

|

| Burial place | Bodenstown Churchyard, Sallins, County Kildare, Ireland |

| Other names | Wolfe Tone |

| Alma mater | Trinity College Dublin King's Inns |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Family | Charles Wolfe (possible half-brother) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United Irishmen French Republic |

| Years of service | 1793–1798 |

| Battles/wars | Irish Rebellion of 1798 |

Theobald Wolfe Tone, often known as Wolfe Tone, was an important Irish leader born on 20 June 1763. He helped start the United Irishmen, a group that wanted Ireland to be free from British rule and have its own fair government.

Wolfe Tone worked hard to bring Irish Catholics and Protestants together for this cause. He also asked France for help to start a big uprising in Ireland. In November 1798, while trying to land in Ireland with French troops, he was captured by British ships. The Irish uprising had already been stopped. Wolfe Tone died before he was to be executed, likely by his own hand, on 19 November 1798.

Later, many people saw him as the founder of Irish Republicanism, which is the idea of an independent Irish republic. His grave in Bodenstown, County Kildare, is a place where people gather every year to remember him.

Contents

Growing Up in Ireland

Wolfe Tone was born in Dublin on 20 June 1763. His father, Peter Tone, was a coach-maker and farmer who belonged to the Church of Ireland (a Protestant church). His family had come from France in the 1500s because they were treated unfairly for their religion. His mother, Margaret Lamport, came from a Catholic family who became Protestant after Theobald was born.

He was named Theobald Wolfe Tone after his godfather, Theobald Wolfe. Many people believed that Theobald Wolfe was actually his father. If this was true, it would make him the half-brother of the poet Charles Wolfe. After his death, he became widely known as Wolfe Tone.

In 1783, Tone worked as a tutor for the younger brothers of Richard Martin, a politician who supported rights for Catholics. Tone thought about becoming an actor for a short time.

He studied law at Trinity College Dublin, where he was very active in the debating club. He graduated in 1786 and became a lawyer at the age of 26.

While he was a student, he ran away with Martha Witherington, who later changed her name to Matilda at his request. They married when he was 22 and she was about 16. He loved her very much, writing in his journal, "She is the delight of my eyes, the joy of my heart, the only object for which I wish to live."

Tone had an idea to start a military colony in Hawaii and sent his plan to the British Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger. When his idea wasn't supported, he thought about joining the East India Company as a soldier, but he applied too late.

Becoming a Politician

In 1791, Tone wrote an important paper called An Argument on behalf of the Catholics of Ireland. He signed it "A Northern Whig". In this paper, he showed that he disagreed with other Irish politicians who wanted to improve Catholic rights but still stay connected to England.

Tone believed that Irish Catholics and Protestants needed to work together to solve Ireland's problems. He felt that Ireland would always be controlled by England and the wealthy Protestant landowners unless Irish Protestants became more open-minded.

Inspired by Tone's ideas, William Drennan suggested forming "a benevolent conspiracy" to his friends in Belfast. This group would work for "Real Independence" for Ireland. In October 1791, Tone joined their first meeting in Belfast. He repeated his belief that Ireland's "imaginary Revolution of 1782" had failed because Protestants and Catholics had not united.

At Tone's suggestion, they called themselves the Society of the United Irishmen. They decided to work for "equal representation of all the people" in parliament. The group grew quickly, especially in Protestant areas of the north, and also in Dublin and the Irish midlands, where they joined forces with a Catholic group called the Defenders.

At first, the United Irishmen only wanted to unite Catholics and Protestants to push for changes in parliament. Because of this, Tone was able to become an assistant secretary for the Catholic Committee in 1792.

The Catholic Committee members in Dublin had different ideas about what steps to take. In December 1791, many members left the committee. In 1793, Tone and other committee members met with King George III in London and were pleased with the meeting. In April, a new law called the Catholic Relief Act was passed. This law allowed Catholics to vote (but not yet become members of Parliament or hold government jobs). They could also become lawyers and army officers again. The Catholic Convention gave Tone £1,500 and a gold medal, and then decided to close down.

However, problems between Protestants and Catholics still threatened the United Irishmen. Two secret groups in Ulster, the Protestant Peep o' Day Boys and the Catholic Defenders, fought each other. Tone wanted to unite all these groups into a revolutionary army of Irish people "with no property."

Tone admitted that his dislike of England was "rather an instinct than a principle." He wanted to remove the popular respect for leaders like Charlemont and Grattan and instead have more radical leaders guide the national movement. Wolfe Tone's ideas were inspired by the French Convention and leaders like Georges Danton and Thomas Paine.

Revolutionary in Other Countries

In 1794, the Society of United Irishmen became a secret group that used oaths to plan the overthrow of the Kingdom of Ireland. Since France and Britain had been at war since 1793, taking such oaths changed the group from one that wanted reforms into a revolutionary one.

The United Irishmen also became more closely linked with the new French Republic. This meant Tone was also associated with France's policy of trying to remove the influence of the church, which the Catholic Church in Ireland strongly opposed. Although Tone was seen as a champion for Catholics in the early 1790s, most of his wealthier Catholic supporters left him in 1794.

Also in 1794, the United Irishmen realized that no group in the Dublin parliament (where only Anglicans could be MPs) would accept their plan for universal manhood suffrage (all men being able to vote) and fair voting districts. So, they began to hope for a French invasion. An Irish clergyman named Reverend William Jackson came to Ireland to see if the Irish people would support a French invasion. Tone wrote a report for Jackson, saying that Ireland was ready for a revolution. However, Jackson's mission was betrayed, and he was arrested for treason in April 1794. He died during his trial.

Many United Irishmen leaders, like Archibald Hamilton Rowan, fled the country. The Dublin government seized the United Irishmen's papers, and the group was temporarily broken up. Tone, who had not attended meetings since May 1793, stayed in Ireland until after Jackson's trial. He was advised to leave Ireland in April 1795. Because he had friends in the government, he made a deal and moved to the United States in May 1795.

Before leaving, he and his family went to Belfast. At the top of Cavehill, Tone made a promise with other Irish radicals, including Thomas Russell and McCracken. They promised "never to stop trying until we had removed England's power over our country, and declared our independence."

The United Irishmen reformed in 1796 and began to seriously look to France for military support for an uprising.

While living in Philadelphia, Tone wrote to Thomas Russell, saying he disliked the American people. He thought they were not truly democratic and were too attached to authority, just like the British. He called George Washington a "high-flying aristocrat" and found the American "aristocracy of money" even worse than the European "aristocracy of birth."

Tone then went to Paris to convince the French government to send an army to invade Ireland. In February 1796, he arrived in Paris and met with French leaders like De La Croix and Carnot. They were impressed by his energy and honesty. He was given a rank as an adjutant-general in the French army. He hoped this would protect him from being charged with treason if he was captured by the British.

A supporter wrote about him, saying: "Wolfe Tone was sent to France to ask for help from the Directory, on the clear condition that the French would come to Ireland as allies, and would follow the directions of the new Irish government, just as Rochambeau had done in America. With this goal, Tone often met with Hoche in Paris; and the Directory finally decided to send a fleet of forty-five ships from Brest, with an army of fifteen thousand men, led by this skilled general, on December 15, 1796. England was saved by a terrible storm."

French Expeditions and the 1798 Rebellion

The French Directory planned a military landing in Ireland to support the revolution that Tone had predicted. The Directory had information from Lord Edward FitzGerald and Arthur O'Connor that confirmed Tone's reports. So, they prepared to send an expedition led by Louis Lazare Hoche. On 15 December 1796, the expedition, with forty-three ships and about 14,450 soldiers, sailed from Brest. They also carried a large amount of war supplies for Ireland.

Tone went with the expedition, using the name "Adjutant-general Smith." He thought the French sailors were not very good at sailing. They could not land in Ireland because of strong storms. They waited for days off Bantry Bay, hoping the winds would calm down, but eventually had to return to France.

Tone then served in the French army under Hoche for several months. Hoche became France's minister of war after winning a battle against the Austrians in April 1797. In June 1797, Tone helped prepare for another military expedition to Ireland, this time from the Batavian Republic (a state created by France in the Low Countries). However, the Dutch fleet was delayed by bad winds and then blocked by a British fleet. When it finally sailed in October, it was quickly defeated by Admiral Adam Duncan in the Battle of Camperdown on 11 October 1797. Tone then went back to Paris. General Hoche, who was supposed to lead an Irish expedition, died of tuberculosis on 19 September 1797.

In Ireland, the United Irishmen had grown to 300,000 members. However, a strong campaign against them in 1797 weakened the group and forced its leaders to start an uprising without French help. Also, in a mostly Catholic country, the Catholic Church was completely against the United Irishmen. This was because the French, who were allies of the United Irishmen, had just invaded Rome and set up an anti-church government there in early 1798.

Napoleon Bonaparte, whom Tone met several times, was less interested in a serious Irish expedition than Hoche had been. When the uprising started in Ireland in 1798, Napoleon had already left for Egypt. When Tone urged the French government to send real help to the Irish rebels, all they could promise were a few small attacks around the Irish coast.

One of these attacks, led by General Jean Humbert, managed to land troops near Killala, County Mayo. They had some success in Connacht before being defeated by General Lake and Charles Cornwallis. Wolfe Tone's brother, Matthew, was captured and hanged. A second attack, with Napper Tandy, failed on the coast of Donegal.

Wolfe Tone took part in a third attack, led by Admiral Jean-Baptiste-François Bompart, with General Jean Hardy commanding about 3,000 men. This group met a British squadron at Buncrana on Lough Swilly on 12 October 1798. Tone was on board the ship Hoche. Bompart offered him a chance to escape in a smaller ship before the battle of Tory Island, but Tone refused. He was taken prisoner when the Hoche surrendered. Tone was brought ashore at Letterkenny Port and arrested.

His Death

When the prisoners were brought ashore two weeks later, Sir George Hill recognized Tone in his French army uniform. At his trial in Dublin on 8 November 1798, Tone gave a speech. He openly stated his strong dislike for England and his goal "by frank and open war to procure the separation of the countries" (to separate Ireland from England through open war).

Knowing that the court would surely find him guilty, he asked to "die the death of a soldier, and that I may be shot" (to be executed by firing squad). However, thinking this was unlikely, he took his own life in prison.

Theobald Wolfe Tone died on 19 November 1798, at the age of 35, in Provost's Prison, Dublin. He is buried in Bodenstown, County Kildare, near where he was born. His grave is cared for by the National Graves Association. With Wolfe Tone's death, the 1798 uprising came to an end.

Support from Lord Kilwarden

Some sources suggest that his godfather, Theobald Wolfe, was Tone's biological father. A cousin, Lord Kilwarden, had warned Tone to leave Ireland in 1795. Then, when Tone was arrested and brought to Dublin in 1798, facing certain execution, it was Kilwarden (a senior judge) who issued two orders for Habeas Corpus to try and release him. This was a remarkable act, especially since the rebellion had just happened with many lives lost. Kilwarden was later killed at the start of Emmet's revolt in 1803, so he could not explain his actions further.

The Wolfe family knew that Tone was their cousin. As a powerful figure in the Protestant ruling class and as the Attorney-General for Ireland, Kilwarden had no other clear reason to try and help Tone in 1795 and 1798. Portraits of Wolfe from around 1800 seem to show a resemblance to Wolfe Tone.

Maud Wolfe (1892–1980), the last of the Wolfe family to live in Kildare, continued her family tradition of laying flowers at Tone's grave every year until she died.

The historian A. T. Q. Stewart commented in 2001 that Tone was very interested in the heroism and death of James Wolfe in 1759, seeing him as a cousin to look up to. In this way, "Wolfe Tone" could be seen as a surname that reflects his true father.

His Lasting Impact

The historian William Edward Hartpole Lecky said that Tone "rises far above the usual level of Irish plots... His understanding of people and events was sharp, clear, and strong, and he was quick to make decisions and brave in action."

Tone's journals, which he wrote for his family and close friends, were published in 1821 by his son, William Theobald Wolfe Tone. They were published again in 1910.

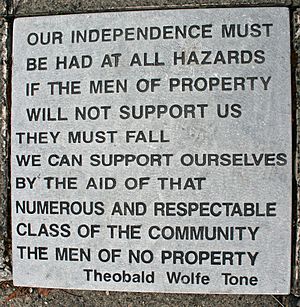

The Young Ireland movement of the 1840s saw Tone as a hero and the founder of Irish republicanism, someone who was above religious differences. Their leader, Thomas Davis, found and made public the location of Tone's grave in 1843. Modern republicans still quote his ideas:

To overthrow the unfair government, to break the connection with England, which is the constant source of all our political problems, and to declare my country's independence—these were my goals. To unite all the people of Ireland, to forget all past disagreements, and to use the common name of Irishman instead of Protestant, Catholic, and Dissenter—these were my methods.

To unite Protestant, Catholic, and Dissenter under the common name of Irishmen in order to break the connection with England, the never-ending source of all our political problems, that was my aim.

If the wealthy people will not support us, they must fail. Our strength will come from that great and respected group, the people with no property.

In 1898, there were many events to remember the 1798 rebellion. These were held by nationalist groups and the Catholic Church in Ireland. However, they often pushed Tone and other Protestant leaders to the side. This "Faith and Fatherland" approach created a myth about Tone and presented the rebellion as something approved by the Church, which was the opposite of the Church's policy in 1798.

Every summer, Irish Republicans hold events at Tone's grave in Bodenstown. In 1912, Tom Clarke, who was later executed after the 1916 Rising, started an annual march from Naas to Bodenstown. This march became a tradition for Irish republican groups, and a new headstone was placed in the 1940s.

In 1934, Protestant Republican Congress members from Belfast tried to join the march but were stopped by IRA stewards. Some people said this showed religious prejudice, arguing that republicans had forgotten Tone's goal of uniting Irish people regardless of religion. However, historian Brian Hanley says the problem happened because they were seen as "communist," not for religious reasons.

From the 1960s, the Wolfe Tone Societies were founded, but they did not have a big impact on mainstream Irish politics. Some members were also connected to the IRA. Because of this, Tone's grave was bombed by the Ulster Volunteer Force in 1971, and then it was rebuilt.

His Family

Of Tone's four children, three died young. His oldest child, Maria Tone (1786–1803), and his youngest child, Francis Rawdon Tone (1793–1806), both died from tuberculosis. Another son, Richard Tone (born between 1787 and 1789), died as a baby.

Only his son, William Theobald Wolfe Tone, lived to be an adult. His mother raised him in France after Tone's death. In 1810, Napoleon ordered him to be trained at the Imperial School of Cavalry. He became a French citizen in 1812. In 1813, he became a sub-lieutenant in the 8th Regiment of Chasseurs and joined the Grand Army in Germany. His nickname was le petit loup – "the little wolf." He fought in several battles, including Löwenberg, Goldberg, Dresden, and Leipzig. He was wounded six times at the Battle of Leipzig, was promoted to lieutenant, and received the Legion of Honour award.

After Napoleon's defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, William moved to the United States. He became a Captain in the United States Army and died there on 11 October 1828, at the age of 37. Matilda Tone also moved to the United States and is buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. William Tone was survived by his only child, his daughter Grace Georgina.

See also

In Spanish: Theobald Wolfe Tone para niños

In Spanish: Theobald Wolfe Tone para niños

| Roy Wilkins |

| John Lewis |

| Linda Carol Brown |