Henry Joy McCracken facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

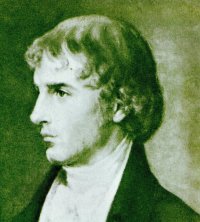

Henry Joy McCracken

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 31 August 1767 High Street, Belfast, Ireland

|

| Died | 17 July 1798 (aged 30) Belfast, Ireland

|

| Cause of death | court-martialled and hanged for treason |

| Occupation | Textile manufacturer |

| Movement | Society of United Irishmen |

Henry Joy McCracken (born August 31, 1767 – died July 17, 1798) was an Irish leader. He was a key member of the Society of the United Irishmen. This group wanted Ireland to be a free and fair country. He also led their fighters during the Irish Rebellion of 1798.

McCracken wanted to bring together different groups in Ireland. He aimed to unite the Presbyterians, who were unhappy with the government, with the Catholic Defenders. In 1798, he led their combined forces in Antrim against the British government. After his group was defeated, McCracken was put on trial by a military court and hanged in Belfast.

Contents

Growing Up in Belfast

Henry Joy McCracken was born in Belfast, Ireland. His family was very important in the city's business world. His father, Captain John McCracken, owned ships. His mother, Ann Joy, came from a family that made a lot of money from linen. Her family, the Joys, were also involved in the Volunteer movement. This was a group of armed citizens. They also started a newspaper called Belfast News Letter.

Henry and his younger sister, Mary Ann McCracken, went to David Manson's school. Manson was a special teacher. He wanted to make learning fun and remove fear from school. This idea might have really influenced Henry.

At Manson's school, students played a game. They pretended to be kings, queens, and tenants. But unlike the real world, everyone earned their rank by working hard. The higher ranks helped the lower ranks. This system taught them about fairness and helping each other. It was very different from the unfair system in Ireland at the time.

In 1788, Henry and Mary Ann tried to start their own school. It was a Sunday morning class for poor children. They taught reading and writing. They decided not to teach religion. They also welcomed children from all backgrounds. This upset some people. A local church leader, Revd William Bristow, stopped their school.

The family's church minister, Sinclair Kelburn, supported the Volunteers. This group allowed Presbyterians to arm themselves. They could practice military drills and meet freely. Kelburn even preached in his military uniform. He pushed for more rights for Catholics. He also wanted fairer elections.

Henry and Mary Ann were inspired by thinkers like Tom Paine. Their mother greatly admired Paine. They also learned from William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft. The siblings loved Irish music too. After the Belfast Harp Festival in 1792, they hosted Edward Bunting. He wrote down many traditional Irish songs.

Joining the United Irishmen

In 1791, Henry Joy McCracken helped start a new group. It was called the Society of United Irishmen. This group wanted to unite all Irish people. They hoped to gain freedom and improve trade. Many of the first members were people Henry knew from his church and the Volunteers. Henry was trusted by the group's leaders from the very beginning.

On March 24, 1795, McCracken formally joined the United Irishmen. He promised to work for "a brotherhood of affection among Irishmen of every religious persuasion." He also swore to get "equal, full and adequate representation of all the people of Ireland." By this time, the group had lost hope in peaceful changes. They started thinking about a rebellion. They hoped France would help them.

In June 1795, McCracken met with Theobald Wolfe Tone. Tone was a key leader of the United Irishmen. They met with other leaders on Cave Hill, near Belfast. There, they made a famous promise. They swore "never to desist in our efforts until we had subverted the authority of England over our country, and asserted our independence." This meant they would not stop until Ireland was free from British rule.

McCracken worked hard to bring people together. He traveled around the country. He tried to calm down fights between different religious groups. He wanted everyone to join the United Irishmen. He even lived in County Armagh for a while. He worked with the Catholic Defenders. He urged them to join the united movement. He also helped pay for legal costs for those unfairly treated.

Closer to home, McCracken worked with Jemmy Hope. They organized Presbyterian farmers and workers in Belfast and nearby areas.

In September 1796, McCracken was arrested. He was put in Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin. But he became very sick. He was released on bail in December 1797, a little over a year later.

Leading the Rebellion

The rebellion began on May 23, 1798, in Dublin and the south. But the north of Ireland did not rise up right away. On June 1, Robert Simms, a leader in Antrim, quit. He didn't want to fight without more help from France. The next day, other leaders were still unsure. So, younger officers chose McCracken to lead.

McCracken was well-known among the Catholic Defenders. This might be why he was chosen. Just days before, he had been rescued by people from Belfast's "Irish quarter." This showed his connection with the Catholic community.

On June 6, McCracken declared the "First Year of Liberty." Many groups gathered across the county. They took control of towns like Ballymena and Randalstown. But they couldn't coordinate their efforts. Most rebels soon went back home. The main battle happened the next evening. McCracken led four to six thousand fighters. They tried to take Antrim Town. But they lost badly.

Catholic Defenders joined the fight. But during the march, there were tensions with the Presbyterian United Irishmen. This might have caused some people to leave. It also delayed McCracken's attack. Meanwhile, the British forces got more soldiers. They surprised McCracken's group.

On June 10, McCracken and about 50 other rebels hid on Slemish mountain. They wanted to join other rebels in County Down. They almost reached Derriaghy. But on June 14, they heard bad news. The United Army of Down had been defeated at Battle of Ballynahinch on June 12. McCracken's group turned back. They were chased by Scottish soldiers and then split up.

His Final Days

McCracken's sister, Mary Ann, met him twice while he was hiding. She gave him money and clothes. In a letter to her, he wrote that the main problem in the country was not religion.

On July 8, Mary Ann heard her brother was in Carrickfergus Gaol. He had been caught trying to get on a ship. He was put on trial by a military court on July 17. He was offered a chance to be set free if he named Robert Simms. But he refused. His last wish to his sister was simple. He asked her to tell his friend Thomas Russell that he had done his "duty."

McCracken was hanged on July 17, 1798. He was 30 years old. The gallows were in front of the Market House in Belfast. This was the same place where he had taught his Sunday school ten years before. He wanted his family minister, Rev. Kelburn, to be there. But Kelburn was too upset. So, Rev. Steel Dickson, who was also held by the authorities, officiated. Henry's last words to his sister were: "Tell Russell I did my duty."

The Market House displayed the heads of other rebels. These were McCracken's friends who had been executed earlier. But General Sir George Nugent allowed McCracken's body to be taken down quickly. He gave it to Mary Ann. She tried to get a surgeon to bring him back to life. But it was too late.

Remembrance

McCracken was buried in St George's Parish Church in Belfast. In 1909, his remains were moved. They were reburied in Clifton Street Cemetery, Belfast. He was laid to rest next to his sister Mary Ann and his daughter Maria. Mary Ann had cared for Maria.

Jemmy Hope was another rebel. He survived the 1798 rebellion. He also survived another attempt to rebel in 1803. He named two of his sons Henry Joy McCracken Hope. Hope remembered McCracken as a loyal leader. He said, "When all our leaders deserted us, Henry Joy McCracken stood alone faithful to the last. He led the forlorn hope of the cause."