Thomas Russell (rebel) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thomas Paliser Russell

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | November 21, 1767 Dromahane, County Cork, Kingdom of Ireland

|

| Died | October 21, 1803 (aged 35) |

| Cause of death | Executed for High Treason |

| Nationality | |

| Occupation | Soldier, Librarian, Revolutionary |

|

Notable work

|

Letter to the People of Ireland (1796) |

| Movement | |

Thomas Paliser Russell (born November 21, 1767 – died October 21, 1803) was an important Irish revolutionary. He helped start the United Irishmen, a group that wanted Ireland to be independent and have a fairer government.

Russell was known for his strong belief in democracy and his ideas about a better future. He was a key leader in Belfast and worked to unite different groups, including the Defenders, who were mostly Catholic farmers. He was arrested before the 1798 rebellion and held until 1802. In 1803, he was executed after trying to get support for Robert Emmet's uprising in Dublin.

Contents

Early Life and Influences

Thomas Russell was born in Dromahane, County Cork, Ireland. His family was part of the "Protestant Ascendancy," which meant they were wealthy Protestants who held most of the power. In the early 1770s, his family moved to Dublin. His father, a soldier, became a Captain at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham.

At 15, Thomas joined his brother's army regiment and went to India. He became an officer in 1783 and fought in the Second Anglo-Mysore War. He was brave in battle, even carrying his wounded commander to safety. Important leaders like Lord Cornwallis noticed him. However, Russell was upset by the unfair treatment of local people he saw there. He returned to Ireland in 1786, feeling disappointed.

For the next four years, he studied science, philosophy, and politics in Dublin. In 1790, he met Theobald Wolfe Tone in the Irish House of Commons. Tone was also critical of the government. Tone later called meeting Russell "one of the most fortunate in my life."

Russell in Belfast

In August 1790, Russell became an officer in the army stationed in Belfast. He joined the city's growing group of professionals and business people. Many of them were Presbyterians who disliked the special treatment given to the Anglican church. They also admired the democratic ideas of the American and French revolutions.

Russell was very smart and had his own strong radical ideas. He became a close friend to many important figures in the United Irishmen movement, including William Drennan, Samuel Neilson, and Mary Ann McCracken.

Russell respected both men and women. Martha McTier and Mary Ann McCracken trusted him. Mary Ann, who thought Russell was very handsome and intelligent, shared her excitement for the ideas of Mary Wollstonecraft. Wollstonecraft wrote about women's rights. Russell agreed, noting that women could be "as clever as men" in many roles.

In October 1791, Russell attended the first meeting of the Society of United Irishmen in Belfast. Theobald Wolfe Tone was there to talk about giving Catholics more rights. Russell spoke about his own discussions with Catholic leaders. The group decided to call for an end to religious tests and for "equal representation of all the people" in the Dublin Parliament.

Russell later worked as a "seneschal" (a type of local judge) in Dungannon. But he was shocked by the anti-Catholic views of other judges and resigned in 1792. This experience made his radical beliefs even stronger. He never again worked for the government. Russell also cared about workers' rights and supported linen workers in their disputes with employers in 1792.

In 1793, Russell became a librarian at the Belfast Society for Promoting Knowledge, which is now the Linen Hall Library. He helped publish traditional Irish melodies collected by his friend Edward Bunting. In 1794, Russell even took classes to learn the Irish language.

A United Irish Revolutionary

When Britain went to war against revolutionary France in 1793, the government became stricter. This made the United Irishmen lose hope in peaceful reform. Instead, they started thinking about a rebellion, hoping France would help. By mid-1793, Russell no longer supported the idea of working with the existing parliament.

In a letter to the United Irish newspaper, the Northern Star, he criticized parliamentary leaders for not making real changes. In a book he co-wrote in 1794, Review of the Lion of Old England, Russell suggested that English laws like Magna Carta and Habeas corpus did little to help ordinary people in Ireland.

In June 1795, Russell met with other leaders of the United Irishmen. At McArt's Fort near Belfast, they took a famous oath. They swore "never to desist in our efforts until we had subverted the authority of England over our country, and asserted our independence." This meant they would not stop until Ireland was free from English rule.

Russell traveled all over Ulster, recruiting people for the United Irishmen. An informer reported that Russell was in charge of all the societies in Ulster. He was so important that he was remembered in a famous song called "The man from God-knows-where."

In 1793, he started a United Irish Society in Enniskillen. His niece, Mary Ann Russell, married William Henry Hamilton, who was also a radical. She remained a close helper and friend to Russell.

Russell's Social Ideas

In 1796, Russell published a book called Letter to the People of Ireland. In it, he shared his strong democratic ideas. He criticized the wealthy ruling class for stopping progress and for being selfish. He believed that all people had a right and a duty to be involved in government. He thought laws should help "the whole family of mankind," not just a few powerful groups.

Russell wanted a simpler, fairer government where God's will could guide decisions, free from greed. He believed this would require big changes to how land and wealth were shared. He said, "The way lands are held makes the people slaves."

He also spoke out against the harsh conditions in factories and the poverty caused by the rich and the government. As a judge in Dungannon, he had supported local linen weavers against their bosses. While some radicals disliked workers forming groups, Russell encouraged workers and farmers to form "combinations" or unions.

Russell was one of the first United Irishmen to believe they would need to rely on "the men of no property." This meant ordinary people who didn't own land or much wealth. While some leaders worried about these "san culottes" (poor people) being in power, Russell was more open to them.

Russell was also strongly against slavery. His friend Mary Ann McCracken remembered that he refused to use products made by enslaved people, even avoiding sugar at dinner parties. Russell also criticized the unfair colonial trade that Belfast was involved in.

A Prisoner of the State

Russell's strong radical views earned him the respect of many democrats in Belfast. He became a key figure in uniting the northern United Irishmen with the Defenders, a large group of ordinary people. The Defenders were a secret group that formed to protect Catholics from attacks.

The government became very worried about these activities. On September 16, 1796, soldiers surrounded Belfast and arrested several United Irish leaders, including Russell. He was charged with "high treason," which means trying to overthrow the government.

Russell was held in Newgate Prison during the 1798 rebellion. He tried to encourage more resistance from prison. In March 1799, he was moved to Fort George in Scotland, where he was held for three more years with other state prisoners.

His letters show that he thought deeply about the world and found comfort in Bible prophecies. He believed that the wars and troubles in Ireland meant that the world was entering a difficult time before a new, better era. He felt it was his duty to fight against the British monarchy.

While at Fort George, Russell and other leaders stayed in touch with Robert Emmet and other young revolutionaries. They planned to rebuild the United Irish Society as a military group. Their goal was to work with France to invade Ireland and England.

In June 1802, during a short break in the war with France, Russell was released. But he had to go into exile in Hamburg.

The 1803 Uprising

Russell did not stay in Hamburg. He soon went to Paris and met Robert Emmet. Emmet was planning a new uprising when the war with France started again. Russell agreed to return to Ireland in March 1803 to organize support in the North. He worked with James Hope and William Henry Hamilton. However, they found that people in the North were tired after the 1798 rebellion and did not want another fight.

When he couldn't get support from the United Irishmen in north Down, Russell tried to rally the Defenders. On July 22, 1803, he spoke to small groups of men in Annadorn and Loughinisland. He told them there would be a big rebellion across Ireland, with attacks in Dublin, Belfast, and Downpatrick. He asked them to join, but they refused. One man said they would just be hanged. On a hill near Downpatrick, where Russell expected a crowd, only three people showed up. One of them even said Ireland might as well be a French colony as an English one.

Russell seemed to have lost touch with reality, still believing in victory despite all the evidence against it. The passion that had helped him in the 1790s now made him unable to see how disappointed people were after the 1798 defeat.

Unknown to Russell, in Dublin, Emmet's plans also failed. He couldn't get the weapons he promised or the support he hoped for. His men revealed themselves too early, and many were not ready to fight. Emmet called off the uprising.

Trial and Execution

Russell managed to hide for several weeks. On September 9, 1803, he was arrested in Dublin by Major Sirr. He had returned hoping to rescue Emmet, who had been captured earlier. Mary Ann McCracken sent money to help him escape, but it was too late. On September 12, he was moved to Downpatrick Gaol.

On October 3, a prison inspector visited Russell. Russell asked to receive a religious service, which he did with great devotion. After the service, Russell declared that he had made mistakes in his life. But he said his political actions were always meant to help his fellow people, even his enemies. He stated he would continue his work no matter what happened.

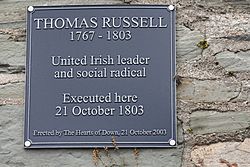

Russell was found guilty of high treason in Downpatrick. On October 12, he was hanged and then beheaded. He was buried in the graveyard of St Margaret's Church in Downpatrick. His friend Mary Ann McCracken paid for his grave.

Before his sentencing, Russell told the court he was surprised to see some jury members who had once shared his political views. He later told an officer that six of the jury members had been United Irishmen themselves.

In 1796, efforts to form a local defense group in Belfast failed due to lack of support. But in 1803, when rumors of Russell's mission spread, the citizens of Belfast declared they were ready to fight any enemies. Two new defense groups were formed. Two of their lieutenants, Robert Getty and Gilbert McIlveen, were former United Irishmen.

The doctor James MacDonnell, who had been Russell's friend, even contributed money for Russell's arrest. MacDonnell had warned Russell that Belfast had changed. While they were friends and MacDonnell had helped Russell get his librarian job, MacDonnell always disagreed with Russell's extreme republican ideas. He thought Russell's political judgment was often too quick and naive.

In his final words to the court, Russell urged the wealthy and powerful to "attend to the wants and distresses of the poor." He told them to care for the working class and their tenants. He suggested that this might not save their position, but it would at least make "their fall... gentle."

Selected Writings

- A Letter to the People of Ireland, on the present situation of the country. Belfast: Northern Star Office, 1796

- Journals and Memoirs of Thomas Russell, 1791-5, Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 1991, ISBN: 0716524821

With William Sampson:

- Review of the Lion of Old England; or Democracy Confounded, Belfast: 1794.

- A faithful report of the trial of Hurdy-Gurdy, tried and convicted of a seditious libel in the court of King's Bench . . .,, (originally serialised in the Northern Star), Dublin: Bernard Dornin, 1806

|

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |