Cotton mill facts for kids

A cotton mill is a large building where machines spin yarn or weave cloth from cotton. These mills were very important during the Industrial Revolution because they helped create the modern factory system.

At first, many mills used water wheels for power and were built near fast-flowing rivers. But after 1781, when better steam engines were invented, mills could be built in cities. This led to the growth of big mill towns like Manchester, England, which had over 50 mills by 1802.

Cotton mills created many jobs, bringing people from farms to cities. They also provided work and income for girls and women. Sadly, child labour was common in these mills. The tough working conditions led to stories that showed how bad things were, and laws called Factory Acts were created in England to make things better.

The idea of cotton mills started in Lancashire, England, but soon spread to New England in America and later to the southern US states. In the 20th century, other countries like the United States, Japan, and China became the main leaders in cotton production.

Contents

- History

- Locations

- Architecture

- Machinery

- Labour Conditions

- Art and Literature

- See also

History

In the mid-1500s, Manchester was already a key place for making wool. People in nearby towns used flax and raw cotton that came in through the Mersey and Irwell Navigation waterways.

Key Inventions

During the Industrial Revolution, making cotton changed from a home-based activity to a factory-based one. This happened thanks to new inventions.

The first machine to speed up weaving was John Kay's flying shuttle in 1733. Then, around 1764, James Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny, which made spinning much faster.

Richard Arkwright patented his spinning frame and water frame in 1769. These machines used rollers to spin cotton. In 1779, Samuel Crompton combined ideas from the spinning jenny and water frame to create the spinning mule. By 1788, there were about 210 mills in Great Britain.

Before 1800, cotton spinning in mills started to grow, first using water power and then steam power from coal.

Successful Early Mills

The Paul-Wyatt Mills

The very first cotton mills were built in the 1740s. They used machines invented by Lewis Paul and John Wyatt that could spin cotton mechanically, without human hands. These machines were powered by a single source, like an animal or a water wheel, allowing production to be gathered in one place.

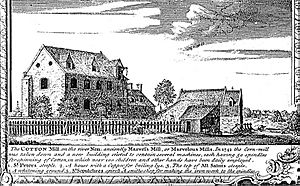

Four mills used Paul and Wyatt's machines. The first was in Birmingham in 1741, powered by animals. Marvel's Mill in Northampton (1742-1764) was the first to use a water wheel. These early mills showed the way for the many cotton mills that came later.

Arkwright-type Mills

Richard Arkwright got a patent for his water frame in 1769. Arkwright was a great organizer and businessman. He turned the cotton mill into a very successful business and a revolutionary example of the factory system.

His first mill in Nottingham (1768) used horses for power. By 1772, it had grown to four floors and employed 300 workers. In 1771, Arkwright started building Cromford Mill in Derbyshire. This mill was a big step forward for the factory system. It was a five-story building, tall and narrow, with many windows. This design became the basic model for cotton mills for a long time.

Arkwright hired many workers and managed his businesses very well. By 1782, he was making over £40,000 a year! He also allowed other business owners to use his technology. By 1788, there were 143 Arkwright-style mills across Britain.

Early mills were narrow (about 2.7 meters wide) and not very tall, with ceilings around 1.8 to 2.4 meters high. They were powered by water wheels and used daylight for light. By the end of the 1700s, Britain had about 900 cotton mills. About 300 of these were large Arkwright-type factories with 300 to 400 workers. The rest were smaller mills, often hand- or horse-powered, with as few as 10 workers.

Early Steam Mills

Before 1780, only water power was available for large mills. This meant mills had to be in rural areas, which made it hard to find enough workers and transport materials.

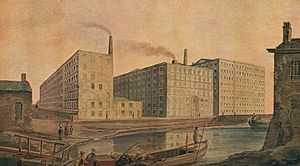

In 1781, James Watt patented the first rotary steam engine that could directly power machines. This invention allowed mills to be built in cities. In 1785, a steam engine successfully powered a cotton mill directly for the first time at Papplewick.

Steam engines changed Manchester's economy. Before, it was a center for home-based spinning and weaving. But with steam power, Manchester quickly became the heart of the cotton industry. By 1800, Manchester had 42 mills.

Mills of this time were often 'L' or 'U' shaped, narrow, and had many floors. The engine house, storage, and offices were inside the mill. Windows were square and smaller than in later mills. The walls were made of plain, rough brick. Some mills were even built to be fireproof.

These mills were typically 25 to 68 meters long and 11.5 to 14 meters wide. They could be up to eight stories high. Power was sent through a main vertical shaft to horizontal shafts on each floor. Later mills used gas lighting, with gas made right there at the mill.

Early Weaving Mills

Mechanizing weaving took longer. John Kay's flying shuttle (1733) had already made home-based weaving faster. The first working power loom was patented by Edmund Cartwright in 1785. It was simple, but it set the basic idea for powered weaving for the next century.

Cartwright opened Revolution Mill in Doncaster in 1788, powered by a steam engine. It had 108 power looms, but it wasn't a business success and closed in 1790. Another mill using Cartwright's machines in Manchester was burned down by angry handloom weavers within two years. By 1803, there were only 2,400 power looms in Britain.

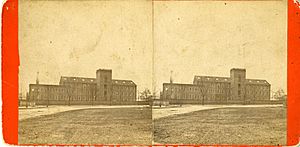

Early American Mills

In the United States, the first horse-powered mill, the Beverly Cotton Manufactory, was built in 1787-1788. This led Moses Brown to seek help from Samuel Slater, a textile worker from England. Slater helped design and build Slater Mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, in 1790. Slater had to sneak out of England because the country wanted to keep its mill technology a secret.

Remodelling and Expansion (1815–1855)

United Kingdom

After 1825, steam engines became powerful enough to run larger iron machines. Mills from 1825 to 1865 usually had wooden floors. William Fairbairn experimented with cast iron beams and concrete floors to make them stronger. Mills were built with red brick or local stone, often with more decoration.

During this time, the spinning machines (mules) became wider, and the spaces between columns in the mills grew. Special architects started designing mills.

Mills became taller, narrower, and wider. They often had one or two wings, forming an 'L' or 'U' shape. Some mills also added single-story weaving sheds with special roofs to let in light from the north. Weaving mills became separate buildings because the vibrations from the looms could damage multi-story buildings.

In 1860, Lancashire had 2,650 cotton mills, employing 440,000 people. Most workers (56%) were women. The mills used a lot of power and imported huge amounts of raw cotton. They exported a lot of cotton cloth and yarn.

This period of fast growth ended around 1860. The Lancashire Cotton Famine (1861–1865) happened when the American Civil War stopped the supply of cotton from America. After the war, the industry changed, and even larger mills were needed.

United States

In 1814, the Boston Manufacturing Company in New England built a "fully integrated" mill in Waltham, Massachusetts. One of its owners, Francis Cabot Lowell, had visited Manchester, England, and remembered details of their mill system, even though Britain tried to stop technology from leaving the country.

The company created the Waltham System, which was copied in new cities like Lowell, Massachusetts. Young women, some as young as ten, worked 73 hours a week for a fixed wage. They lived in company-owned boarding houses and went to company-supported churches.

In the 1840s, George Henry Corliss improved stationary steam engines, making them more reliable and efficient. These Corliss valves were later used in UK mills too.

India

The modern factory-based textile industry in India began in 1854 when a steam-powered mill opened in Bombay. More mills followed, and by 1880, India had 58 mills employing 40,000 workers, mostly in Bombay and Ahmedabad. By the 1870s, India's own markets were no longer controlled by imports from England.

Golden Age (1855–1898)

United Kingdom

Around 1870, a new way of funding mills, called "joint-stock spinning companies" (like the Oldham Limiteds), led to a new wave of mill building. Joseph Stott developed a fireproof floor using steel beams and concrete, which could support heavier machines.

Engines ran at higher pressures, and from 1875, they powered machines using ropes instead of gears. This meant a special "rope race" had to be built, running the full height of the mill. Mills continued to get bigger, sometimes with two mills driven by one engine.

Mills became wider. Houldsworth Mill, Reddish (1865) was 35 meters wide and held 1,200 spinning machines. It was four stories high with a central engine house. Mills also had other buildings like offices and warehouses. Stair towers often went above the mill and held water tanks for fire sprinklers.

The power needed for these mills kept growing. By the 1890s, boilers produced very high pressure steam, and chimneys became octagonal.

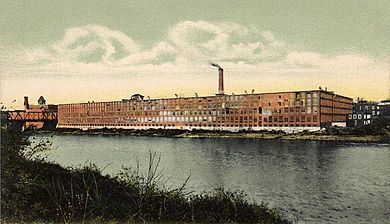

United States

After the American Civil War, cotton mills were built in the southern states like South Carolina, Alabama, and Mississippi. These mills grew larger because cheap labor and plenty of water power made them very profitable. This meant cotton could be turned into fabric right where it grew, saving money on transport.

These mills usually combined spinning and weaving. They were often in the countryside, and new mill towns grew up around them to support the workers. Mills in New England found it harder to compete and slowly declined until the Great Depression.

Asia

The modern Indian textile industry started in 1854. By the 1870s and 1880s, the Bombay cotton industry began to take over from British exports of yarn to China.

Edwardian Mills (1898–1914)

The cotton industry went through cycles of good times and bad times. There was a belief that bad times would pass, leading to even greater success. The industry reached its peak in 1907.

United Kingdom

Cotton production in Britain peaked in 1912. The First World War (1914–1918) hurt the industry. The British government, needing cotton, set up mills in South Asia and exported spinning technology. This technology was copied, creating new competitors with lower labor costs.

New mills built during this time were very large to save money by producing more. Older mills were updated with newer machines and individual electric motors.

These Edwardian mills were huge and had fancy decorations, showing the wealth of the time. They were often built for spinning mules. For example, Kent Mill in Chadderton (1908) was a five-story mill with 90,000 spindles. Ring frames were smaller and heavier than mules, so mills for them were narrower with fewer stories.

More powerful engines needed more boilers and water. Mills often had reservoirs to supply water for the boilers and to cool the steam. Chimneys became round and taller. Electricity was slowly introduced, first to power groups of machines, and later to power individual machines.

United States

Mills in South Carolina grew in size. For example, at Ware Shoals, a large power plant was built in 1904, followed by a modern textile mill in 1906. This mill had 30,000 spindles. By 1916, a new mill was built with 70,200 spindles and 1,300 looms. The town of Ware Shoals grew from just two workers in 1904 to 2,000 people. By the 1960s, the mill employed 5,000 people, but it closed in 1985.

Consolidation (1918–50)

After 1919, business picked up, but building new mills was difficult due to a lack of materials. The industry focused on financial changes. Some people think the decline happened because cotton businesses focused on quick profits instead of updating their mills to compete with foreign companies. Others believed there was too much production capacity.

The Lancashire Cotton Corporation was created in 1929 by the Bank of England to save the spinning industry by combining many companies. It merged 105 companies and by 1950, it had 53 working mills. These were the larger, more modern mills. This corporation was bought by Courtaulds in 1964.

The last mills were finished in 1927, including Holden Mill and Elk Mill. By 1929, the USA had more spinning machines than the UK. India surpassed the US in 1972, and China surpassed India in 1977.

Cotton Mills in the Late 20th Century (1950–2000)

Decline of Spinning in England

Even with a small recovery after 1945, many mills closed. The most efficient mills had switched from steam engines to individual electric motors for their machines. Broadstone Mills Stockport, a huge mill built with 265,000 spindles, closed in 1959. It was then used by a mail order company, and one part of the mill was later torn down.

The closing of mills left many empty buildings, which were often used for other industrial purposes. In the 1970s, a new technology called open-end spinning challenged the industry. In 1978, a new factory for open-end spinning opened in Atherton, the first new textile factory in Lancashire since 1929.

Modern Cotton Mills

Modern spinning mills mainly use open end spinning (rotors) or ring spinning (spindles). In 2009, most of the world's spinning machines were in Asia and Oceania, especially China. Open-end spinning machines are much more productive than spindle machines.

Modern cotton mills are becoming more and more automated. For example, a large mill in Virginia, USA, employed only 140 workers in 2013 to produce what would have needed over 2,000 workers in 1980.

Locations

Cotton mills were built in many places, not just Lancashire. They were found in parts of Cheshire, Derbyshire, Nottingham, Yorkshire, Bristol, Durham, and western Scotland. Early mills needed fast-flowing streams for power, so they were often in isolated areas. In Lancashire, they were built along rivers coming down from the Pennines.

In Scotland, four cotton mills were built in Rothsay on the Isle of Bute. By 1800, there were two water-powered mills at Gatehouse of Fleet employing 200 children and 100 adults. Robert Owen, who had worked in Manchester, developed the mills at New Lanark, which were built by his father-in-law, David Dale.

| Lancashire | Cheshire | Derbyshire | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mills | 1920 | 200 | 25 |

| Workers | 310000 | 38000 | 12000 |

Architecture

Fireproof Construction

Cotton mills were very dangerous places for fires. Cotton fibers in the air could explode, especially with gas lighting. The first mills designed to be fireproof were built in Shropshire and Derbyshire in the 1790s. One famous example was Philips & Lee's mill in Salford (1801–1802).

Fireproofing involved using cast iron columns and beams that supported brick arches, which were then filled with ash or sand and covered with stone or wooden floors. In some mills, even the roof was made of iron. However, early cast iron structures sometimes collapsed because people didn't fully understand how strong they were. Fireproof construction was expensive, so wood was still used throughout the 19th century, sometimes covered in plaster or metal.

Other Factors

Cotton needs specific temperature and humidity to be spun properly. Heating systems used iron pipes with steam to keep the mill warm. In winter, boilers would be started two hours before work to heat the mill. As the heat increased, humidity dropped, so humidifiers were used to add moisture to the air.

Early fire fighting systems used sprinklers fed by water from shallow tanks on flat roofs. Later mills had a water tank at the top of the stair tower. The design of the mill was influenced by the need for light, water tanks, and heating systems.

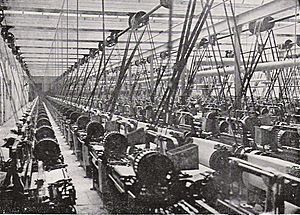

Machinery

Power

The first cotton mills were powered by water, so they had to be located near fast-flowing streams. From about 1820, the stationary steam engine became the main power source for cotton mills. Water was still needed to make steam, cool it, keep the air humid, and for fire fighting. Mills got water from rivers and canals, and later, larger mills built their own reservoirs.

In 1781, James Watt created a steam engine that could turn a wheel, making it useful for all kinds of machines. Richard Arkwright was one of the first to use it in his cotton mills.

Electricity was introduced in 1877. Steam engines powered generators to provide electric lighting. By the 1890s, this was common. By 1906, electricity was used to power the mill's machines. Later mills used individual electric motors for each machine.

Transmission

Early mills had a vertical shaft that took power from the engine's flywheel. On each floor, horizontal shafts connected to the main shaft using gears. American mills sometimes used thick leather belts instead of shafts. A new method used thick cotton ropes. A special drum on the flywheel had grooves for each rope, ensuring maximum grip.

Spinning

In a spinning mill, raw cotton bales were opened and cleaned. The cotton fibers were then combed and stretched into a thick rope called "roving." This roving was then spun into yarn using either a spinning mule or a ring frame. The yarn could then be twisted into thread or prepared for weaving.

The self-acting mule frame (invented by Roberts in 1830) was an improvement on Crompton's original mule (1779). Mules were used in 19th-century mills to make the finest yarns and needed skilled workers.

The ring frame (1929) developed from earlier machines. At first, rings were only good for thicker yarns. They were heavier and lower than mules, so they needed stronger floors but lower rooms. Over time, rings could make finer yarns, and because they needed less skilled labor, they replaced mules. By 1950, most mills had switched to the ring frame.

Weaving

A weaving mill needed yarn for both the length (warp) and width (weft) of the fabric. The warp yarn was prepared on a large roller called a beam. To make it stronger, the yarn was treated with a sizing liquid. The weft yarn was wound onto small bobbins called pirns for the shuttle. Once prepared, the yarn was woven on a loom. One weaver might operate four or six looms. A self-acting loom would stop if a thread broke, and the weaver would fix it. Weaving needed a lot of light, so weaving sheds were often single-story buildings with north-facing skylights. Placing looms on the ground also reduced problems from their vibrations.

Cartwright's power loom (1785) was made more reliable by Robert's cast iron power loom (1822) and perfected by the Kenworthy and Bullough Lancashire Loom (1854). Later, the Northrop Loom (1895) replaced these older designs.

| Year | 1803 | 1820 | 1829 | 1833 | 1857 | - | 1926 |

| No. of Power Looms in UK | 2,400 | 14,650 | 55,500 | 100,000 | 250,000 | 767,500 |

| Year | 1823 | 1823 | 1826 | 1833 |

| good hand loom weaver | power weaver | power weaver | power weaver | |

| Aged 25 | Aged 15 | Aged 15 | Aged 15 with 12yr old helper | |

| Looms | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Pieces woven per week | 2 | 7 | 12 | 18 |

Labour Conditions

Cotton mills were known for employing many women, which gave them their own income. In both Lancashire, England, and Piedmont, South Carolina, the use of child labor is well known.

Child Labour in the United Kingdom

Mills in Lancashire and Derbyshire needed cheap workers. Pauper children were boys and girls aged 7 to 21 who were cared for by the Poor Law Guardians. Mill owners made deals with these guardians to get groups of 50 or more children as apprentices. Living conditions in the 'Prentice Houses' were poor. Children worked 15-hour shifts and often shared beds with children from the other shift.

Robert Owen, a mill owner in New Lanark, never hired children under ten. He was against physical punishment in schools and factories. He pushed for laws, which led to The Health and Morals of Apprentices Act 1802. This law:

- Limited work hours to twelve a day.

- Required boys and girls to sleep in separate dormitories, with no more than two to a bed.

- Made education in reading, writing, and arithmetic compulsory.

- Required each apprentice to have two suits of clothes.

- Stated that children should be taught Christian worship on Sundays.

- Called for better sanitation.

These rules weren't very effective until 1833, when factory inspectors were appointed. These inspectors had the power of magistrates. The number of children working full-time in spinning did go down, but more children were employed in weaving. Many children worked "half-time," spending mornings in the mill and afternoons in school.

| Year | 1835 | 1838 | 1847 | 1850 | 1856 | 1862 | 1867 | 1870 | 1874 | 1878 |

| amount | 13.2 | 4.7 | 5.8 | 4.6 | 6.5 | 8.8 | 10.4 | 9.6 | 14.0 | 12.8 |

In 1851, many children still worked in mills. For example, in Glossop, 931 children (out of 3,562) between 5 and 13 worked in cotton mills.

Child Labor in the United States

Mills in the Carolinas, which grew from 1880, often preferred to hire children over adults. In 1909, at Newton Mill, North Carolina, about 20 out of 150 workers seemed to be 12 years old or younger. Besides the usual reports of injuries and terrible heat, the cotton dust caused a serious lung disease called brown lung.

Laws were rarely enforced. When inspectors visited, the presence of small children was often explained by saying they were just visiting to bring meals to their parents or helping without being paid. Wages were good for workers, who could earn $2 a day in the mill compared to $0.75 on a farm. In the segregated South, Black workers were not allowed inside the mills. If they had been, there might not have been a need for child labor. Child labor eventually stopped due to new laws and changes in machinery that required taller and more skilled workers.

Women

In 1926, at its peak, the Lancashire cotton industry had 57.3 million spinning machines and 767,500 looms. It imported 3.3 million bales of cotton and exported 80% of what it produced. Of the 575,000 cotton workers in Lancashire, 61% were women. Many of these women were part of unions.

Unions

In Lancashire cotton mills, spinning became a job for men, and the tradition of unions moved into the factories. Spinners were assisted by "piecers," creating a pool of trained workers who could replace any spinner the owner fired. The well-paid mule spinners were known as the "barefoot aristocrats" of labor and formed strong unions in the 19th century. They paid high union fees, which gave them large funds to use if a strike was needed.

In 1913, about 50% of cotton workers in Lancashire were unionized.

| Occupation | Union members |

|---|---|

| Weavers | 182,000 |

| Cardroom Operatives | 55,000 |

| Spinners | 23,000 |

| Piecers | 25,000 |

Health of the Workers

A cotton mill was not a healthy place to work. The air had to be hot and humid (18°C to 26°C and 85% humidity) to stop the thread from breaking. The air was also full of cotton dust, which could cause a lung disease.

Protective masks were introduced after the war, but few workers wore them because they were uncomfortable in the hot, stuffy conditions. The same was true for ear protectors. The air also led to skin and eye infections, bronchitis, and tuberculosis. The noise levels in a weaving shop, with hundreds of looms thumping loudly, caused deafness in almost everyone who worked there.

A mill worker typically worked a thirteen-hour day, six days a week, with only two weeks off for summer holidays. Because of these conditions, a series of Factory Acts were passed to try and make things better.

In the early days, as cotton towns grew very quickly, living conditions for workers were poor. Housing was overcrowded, and open sewers led to diseases like cholera. Manchester, for example, had a cholera outbreak in 1831 that killed hundreds of people.

Art and Literature

- William Blake: "And did those feet in ancient time" (1804 poem, which mentions "dark satanic mills")

- Mrs Gaskell : Mary Barton (1848 novel), North and South (1855 novel)

- L. S. Lowry: Coming from the Mill (1930 oil painting)

- Charles Sheeler

See also

- Cotton famine

- Cottonopolis

- Stott, cotton mill architects

- Textile manufacturing

- Water frame

| John T. Biggers |

| Thomas Blackshear |

| Mark Bradford |

| Beverly Buchanan |