Lancashire Cotton Famine facts for kids

The Lancashire Cotton Famine (1861–1865) was a very tough time for the textile industry in North West England. It happened because there was too much cotton cloth made, more than people wanted to buy. At the same time, the American Civil War stopped ships from bringing raw cotton to Britain. This caused cotton prices to shoot up.

Before the famine, factories had made so much cotton cloth that they couldn't sell it all. This meant they needed to slow down production. The problem got worse because there was also a lot of raw cotton stored in warehouses. This made prices for finished goods drop, while the demand for raw cotton fell.

However, the American Civil War changed everything. The war stopped cotton imports, and the price of raw cotton went up by hundreds of percent. Without raw cotton, many factories in Lancashire had to close. Thousands of workers lost their jobs. They went from being some of the richest workers in Britain to the poorest.

Local groups quickly started helping people. They asked for money from local areas and across the country. Two main groups were the Manchester Central Committee and the Mansion House Committee in London. The poorest people got help through the old Poor Laws. Local groups also set up soup kitchens and gave direct aid.

In 1862, churches started sewing classes and other training. People who attended these classes could get money from the Poor Law. Later, a law called the Public Works Act (1864) allowed local councils to borrow money. They used this money to build new sewer systems, clean rivers, create parks, and fix roads. By 1864, cotton imports started again, and factories reopened. But some towns had found new industries, and many workers had moved away.

Contents

Why the Cotton Famine Happened

The years 1859 and 1860 were amazing for the cotton industry in Lancashire and nearby areas. Factories made huge amounts of printed cotton cloth. They even sent a lot to India. Some mill towns grew very fast. But this huge growth meant a slowdown was coming.

Then, in 1861, the American Civil War began. The Southern States, where most of the cotton came from, wanted to leave the United States. They stopped sending cotton to Britain, hoping to force Britain to help them. The North then set up a blockade to stop any ships from leaving or entering Southern ports. This cut off the main supply of cotton to Britain.

In 1860, there were 2,650 cotton factories in the region. They employed 440,000 people. Most of these workers were adults, and more than half were women. These factories used a lot of power and had millions of spindles and power looms. Britain imported most of its raw cotton from America.

| Lancashire | Cheshire | Derbyshire | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mills | 1,920 | 200 | 25 |

| Workers | 310,000 | 38,000 | 12,000 |

| Country | Imports (lb) |

|---|---|

| America | 1,115,890,608 |

| East Indies | 204,141,168 |

| West Indies | 1,630,784 |

| Brazil | 17,286,864 |

| Other | 52,569,328 |

The First Year of Trouble

Even before the war, unsold cloth was piling up in warehouses. Factories were already making too much. When the American Civil War looked likely, American cotton growers quickly sent their cotton to Britain. Enough cotton arrived in Liverpool in 1861 to keep the mills going for a while.

People thought the war would be short. But as the Northern forces struggled, it became clear the war would last longer. By December, cotton prices were rising fast. Merchants held onto their cotton, hoping prices would go even higher.

By early 1862, factories started closing, and workers lost their jobs. In one cotton town, a third of families needed help. The price of cotton, which cost very little to grow, shot up dramatically. Merchants who had stored cotton made huge profits.

Using Different Cotton

The best quality cotton came from the islands off America's Carolina coast. Egyptian cotton was the second best. Most factories in Lancashire used a common type of American cotton.

Cotton from India, called Surat cotton, was not as good for machines. Its fibers were short and broke easily. It also came in smaller bales with stones and dirt mixed in. Factories usually only used a small amount of Surat cotton in their mixtures.

When American cotton stopped coming, factory owners had to use Surat cotton. Some machines could be changed to use it, but they needed more humidity to stop the fibers from breaking. Using Surat cotton meant machines worked much slower, producing only about 40% of what they used to. Since workers were paid by how much they made, their wages dropped a lot.

Many smaller, family-owned factories had loans. If they stopped running, they couldn't make payments. Shopkeepers had no customers and couldn't pay rent. Workers couldn't pay their rent either. Often, the factory owner was also the landlord and lost money.

Richer factory owners believed the famine was temporary. They planned to buy new, more efficient machines. For example, Henry Houldsworth built a huge new factory during this time. With little raw cotton available, owners either closed their mills, helped workers, used poor quality cotton, or tried to find new cotton sources. Surat cotton was available but mostly used in India. Some efforts were made to grow cotton in Australia and near Mumbai.

How People Suffered

The cotton industry was very specialized. How badly a town was affected depended on many things. Some towns used short-fiber American cotton, while others used longer Egyptian cotton, which was still available. Some machines could be changed to use different cotton, others could not. Factories that did both spinning and weaving could manage their work better. Some careful owners always kept cotton in stock, while others bought it only when needed.

Older factory owners who lived in the community helped their workers. For example, in Glossop, Lord Howard brought together factory owners, church leaders, and other important people. They formed two relief groups. They tried soup kitchens, but those didn't work well. Instead, they gave out thousands of pounds worth of food, coal, shoes, and clothes.

A calico printer named Edmund Potter loaned money to his workers. Lord Howard hired extra workers for his estate. They also set up schools, gave free brass band concerts, and read from books like the Pickwick Papers. After the 1864 Public Works Act, they borrowed money to expand the water system. The only problem was when the relief group tried to sell, instead of give away, food sent from the American government.

Towns with many small factories that rented space and machines did well at first. But when cotton became scarce, these were the first to go bankrupt. After the famine, bigger, more advanced factories were needed. Many private owners couldn't afford this. So, new companies were formed to build these larger mills. Local councils couldn't borrow money for public works until the 1864 Act. Before that, they had to use their own savings, which varied from town to town.

The "Panic" and Moving Away

Some workers left Lancashire to find jobs in the wool industries in Yorkshire. A few factories even changed to making wool. Towns like Stockport and Hyde started making hats. The area around Tameside was hit hardest and lost many people between 1861 and 1871.

By 1864, there were thousands of empty houses and shops in towns like Stockport and Glossop. Many people were forced out of their homes. Special agencies helped people move away. Shipping companies lowered their prices for trips to places like New York. The governments of Australia and New Zealand even offered free travel. By August 1864, about 1,000 people had moved away, including 200 from Glossop.

Helping Those in Need

Help for poor people was managed by the old Poor Law Act. This law said that Poor Law Guardians had to find work for healthy people. In the countryside, this meant breaking stones or working in mines. But this kind of hard outdoor work was not good for factory workers, whose lungs were often damaged by cotton dust. The law only required that men work as long as they received help.

The Poor Law Amendment Act 1834 had created Poor Law Unions to manage aid. Their goal was to keep costs low for local areas, which had to pay for their own poor. People needing help were supposed to be sent back to their home towns.

Charles Pelham Villiers, a Member of Parliament and Poor Law Commissioner, warned the Poor Law Unions in September 1861 about the coming famine. He told them to be kind. Money had to be raised locally through taxes. An official named H. B. Farnell was sent to investigate in Lancashire. He said that gifts from charities should not stop people from getting help.

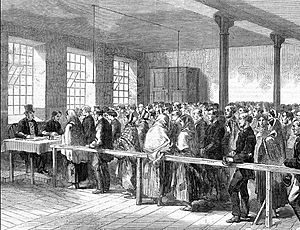

Instead of outdoor work, churches started sewing classes. People who attended these classes could get benefits. Then came Bible reading classes, followed by industrial classes that taught reading, writing, simple math, carpentry, shoemaking, and tailoring.

The Poor Law Unions could only raise a limited amount of money through taxes and couldn't borrow. So, Parliament passed the Union Relief Aid Bill 1862. This allowed the cost of relief to be shared between different towns and the county. Then, the Public Works (Manufacturing Districts) Act 1864 allowed them to borrow money.

Everyone who had a job was encouraged to give to charity. Lists of people who gave money were published. Local relief groups managed these funds. They also received donations from the Mansion House Committee in London and the Central Relief Committee in Manchester.

The Mansion House Fund started on May 16, 1862. It sent £1,500 (a lot of money back then) to the struggling areas. People from all over the United Kingdom, the British Empire, and even other countries raised money. Between April 1862 and April 1863, over £473,000 was collected and given out. The Central Committee, made up of mayors from the affected towns, formed on June 20, 1862. They asked other towns across the country for help.

The Stalybridge Riot

By the winter of 1862–1863, about 7,000 workers in Stalybridge had no jobs. This was one of the worst-hit towns. Only five of the town's 39 factories were working full-time. Money came from all over the world to help cotton workers in Cheshire and Lancashire. At one point, three-quarters of Stalybridge workers relied on relief programs. By 1863, there were 750 empty houses in the town. A thousand skilled workers left in what was called "The Panic."

In 1863, the local relief committee decided to give out tickets for food instead of money. These tickets could be used at local grocery stores. On Thursday, March 19, a public meeting decided to fight against the tickets.

On Friday, March 20, 1863, officials went to the thirteen schools where people received aid. The men refused the tickets and went into the streets. They threw stones at an official's taxi and broke the windows of shops owned by members of the relief committee. Then they attacked the relief committee's offices and took things. By evening, soldiers arrived from Manchester. The Riot Act was read, and eighty men were arrested. Women and girls continued to shout at the police and soldiers.

On Saturday, March 21, most prisoners were released, but 28 were sent for trial in Chester. Police and soldiers took them to the train station, and people threw stones at them. Another public meeting demanded "money and bread," not "tickets." Rioters demanded bread at various shops, and they were given it. Later that night, more soldiers arrived and patrolled the streets with bayonets.

On Sunday, supporters came to town, but nothing happened. On Monday, March 23, the riot spread to nearby towns like Ashton and Hyde. Schools had reopened, but only 80 of the expected 1,700 students attended (they were still being paid by ticket). People were sent to schools in neighboring towns to get students to walk out, but they were met by soldiers.

On Tuesday, the protests ended. The relief committee offered to pay the tickets that were owed and to meet with representatives from the thirteen schools to talk more. The mayor offered that the local MP, John Cheetham, would take the issue to Parliament. The crowd believed they would not lose their aid and that the ticket system would soon be stopped.

The Stalybridge relief committee got control back. The Manchester Central Committee criticized their poor management. But they were also being challenged by the Mansion House Fund, which offered to give cash directly to people through churches. The violence was blamed on outsiders and a minority of immigrants. About 3,500 people were involved, even though only 1,700 people were getting aid.

Public Works Act of 1864

By March 1863, about 60,000–70,000 women were attending sewing schools, and 20,000 men and boys were in classes. This was seen as useful work, so they could legally receive help under the Poor Law. But another 25,000 men were getting aid without doing any work. People at the time thought this was wrong, and they needed a way to provide paid work.

Local councils had work that needed doing, but no legal way to borrow money to pay for it. The Public Works Manufacturing Districts Act became law on July 2, 1863. This law allowed public authorities to borrow money for public works. Cotton workers could now be hired for useful projects.

Because of this, many municipal parks were created in Lancashire, like Alexandra Park, Oldham. Even more important were the new main sewers. These were built to replace old, broken drains and bring sanitation to the hundreds of small houses where mill workers lived. Canals were dug, rivers were straightened, and new roads were built, like the cobbled "Cotton Famine Road" near Norden. The public works from this time greatly improved the towns of Lancashire and the surrounding cotton areas.

Cotton Returns

A small amount of raw cotton started reaching Lancashire in late 1863. But it didn't get to the worst-hit areas, as it was quickly used up in Manchester. The cotton was mixed with stones, but its arrival meant that factory owners could bring back key workers to get the mills ready.

The American Civil War ended in April 1865. In August 1864, the first large shipment of cotton arrived. Wooley Bridge mill in Glossop reopened, giving all workers a four-and-a-half-day week. Soon, employment returned to normal. Raw cotton prices had risen sharply during the famine, but they started to come down.

Politics and Support

The Southern States hoped that the suffering in European cotton areas (France also faced problems) would make Europe step in and force the North to make peace. After the North stopped a Southern attack in September 1862, Abraham Lincoln announced his Emancipation Proclamation. This declared that many enslaved people in the South were free.

Slavery had been ended in the British Empire many years earlier. People who supported the North believed that the British public would now see the war as being about ending slavery, not just about trade. They hoped this would pressure the British government not to help the South. However, many factory owners and workers were angry about the blockade. They still saw the war as a fight over trade rules. Some ships tried to get around the blockade from Liverpool, London, and New York. In 1862, over 71,000 bales of American cotton reached Liverpool. Confederate flags were even flown in many cotton towns.

On December 31, 1862, cotton workers met at the Free Trade Hall in Manchester. Even though they were suffering greatly, they decided to support the North in its fight against slavery.

On January 19, 1863, Abraham Lincoln sent a letter thanking the cotton workers of Lancashire for their support. He wrote that he understood their suffering and praised their "sublime Christian heroism" for supporting human rights. He hoped this would lead to lasting peace and friendship between the two nations.

A monument in Manchester, England, remembers these events and includes parts of Lincoln's letter. The American government also sent gifts of food to the people of Lancashire.

Impact Around the World

To deal with the cotton shortage, Britain tried to get cotton from other places. They encouraged farmers in British India, Egypt, and other areas to grow cotton for export. Often, this meant they grew less food. When the American Civil War ended, these new cotton farmers were no longer needed, and their cotton was not in demand. This made them poor and made famines worse in these countries later in the 19th century.

In China, British trade had increased after the Second Opium War. But when the American Civil War started, cotton prices became so high that China stopped buying from outside. The textile trade in China lost two-thirds of its value from 1861 to 1862 and kept falling.

Some regions, like Australia, welcomed skilled cotton spinners and weavers and encouraged them to move there.

What We Learned

In 2015, a historian named Walker Hanlon found that the cotton famine greatly changed how textile machines were made. Especially for machines that cleaned and prepared Indian cotton. One major company, Dobson & Barlow, tried four different machine designs in four years. They also reduced wasted Indian cotton by 19-30% between 1862 and 1868. This shows that the need for new cotton sources led to new inventions.

In 2022, a folk band called Bird in the Belly turned two poems from the University of Exeter Cotton Famine Poetry Archive into songs for their album After the City.

|

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |